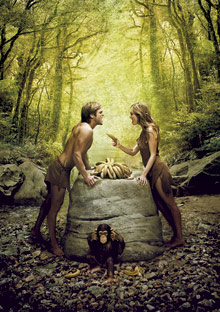

Photo Illustration: Jonathan Barkat

When all hell breaks loose, does that mean the two of you are really in trouble? Mark Epstein used to think so…

One of the first fights my wife and I ever had, some months into our marriage, was about how to wash lettuce. It was a small thing that flared into a big thing, and it sent me running to my therapist for help in putting out the fire. We were newly married, and making dinner after work in our new apartment. I was preparing the salad, and my wife made a suggestion that I heard as a criticism. Or perhaps she criticized me and then claimed she was making a suggestion; it depends on who you want to believe. In any case, suddenly we were at odds. Things had gone wrong. Our unity, our very love for each other, was disrupted. Our marriage, the foundation of all that we believed in, was under siege. She thought I was oversensitive and ridiculous. I thought she was controlling and unapologetic. We could not see eye to eye. I had trouble even looking at her.I was still angry when I went for my therapy appointment, but frustrated and sheepish and confused as well. "I suppose all I can do at these times is love her all the more strongly," I said to my therapist, drawing on my reserve of good intention, my belief in my marriage, and my conviction that by force of will I could get these troublesome feelings out of the way. I was frightened to be at odds with the person I most needed and was willing to do whatever my therapist suggested to make things better.

"Love her more strongly? That will never work," he replied with barely concealed disdain. "What's wrong with being angry?"

For me, this was a new concept. What's wrong with being angry? Everything! I did not want to be angry, I did not want her to be angry, and I did not want our marriage to have anger within it. I wanted peace and harmony and attunement and love—and sex. And yet, when I heard these words, something in me relaxed. It was okay to be angry? This did not mean that our marriage was bad? This rupture could be repaired?

Just the other day, an old friend told me a story about her marriage. She and her husband of many years were reminiscing about Paris, planning their next visit there. It had been 10 years. The last time they were there, they had a big fight on the street. The husband was so mad that he took all the money out of his pockets and threw it onto the street along with his jacket and books. He went straight to the airport and flew home without his wife, leaving her, she said with a smile, to have three more wonderful days in Paris. When he arrived in the States, he didn't have enough money to get home from the airport and had to call a friend in the middle of the night to come pick him up. The friend told him he was crazy and said to call back in a few hours. The husband actually walked from the airport. The funny thing was, she said, neither of them could remember what they'd been fighting about! Here was a couple who could be angry with each other without it being a catastrophe, who could even laugh about it without any apparent bitterness. She made it seem so easy.

My friend, like my therapist years before, was opening up a new model of successful marriage, one in which a reliance on a state of attunement gives way to an appreciation of a cyclic process of rupture and repair. This is a model gaining traction in the therapy world, one based on a change in how the most successful intimate human relationships are now understood. My friends' ability to take their differences in stride, to return after disruption to an appreciation of their connection, to laugh together about their differences, was a reflection of this shift to a more process based model of success. My difficulty allowing anger to be a natural emotion within marriage reflected the older model that values attunement above all else.

Psychologists who study the origins of intimacy in mother-infant relations support this shift in emphasis. The template for all intimate relationships is the one between infant and parent. Studies of these relationships have exploded the myth of the 100 percent responsive mother. Research suggests that the best parents are fully attuned to their children only about 30 percent of the time, leaving lots of space for failure. D.W. Winnicott, a pioneering British child analyst of the last century, laid the foundation for this shift with his concept of the "good-enough mother." Parents cannot possibly be at one with their children all the time, he suggested. Babies are not benign beings emitting only love. They are rapacious creatures who love ruthlessly, and who, as often as not, bite the hand, or breast, that feeds them.

The good-enough mother is one who can tolerate her infant's rage as well as her own temporary hatred of her child; she is one who is not sucked into retaliating or abandoning, and who can put aside her own self-protective responses to devote herself adequately (remember the 30 percent figure) to her child's needs. This "good enough" response, while not denying her own hatred, teaches the child that anger is something that can be survived. Winnicott wrote about how the child whose mother survives his or her destructive onslaught learns to love her as an "external" person, as an "other," not merely as an extension of themselves. This child recognizes that the mother has survived the attack and feels something on the order of joy or gratitude or relief, a dawning recognition that mother is outside his or her sphere of omnipotent control. This is the foundation of caring for her as a separate person, what we call consideration or concern or empathy.

Psychologists who study the origins of intimacy in mother-infant relations support this shift in emphasis. The template for all intimate relationships is the one between infant and parent. Studies of these relationships have exploded the myth of the 100 percent responsive mother. Research suggests that the best parents are fully attuned to their children only about 30 percent of the time, leaving lots of space for failure. D.W. Winnicott, a pioneering British child analyst of the last century, laid the foundation for this shift with his concept of the "good-enough mother." Parents cannot possibly be at one with their children all the time, he suggested. Babies are not benign beings emitting only love. They are rapacious creatures who love ruthlessly, and who, as often as not, bite the hand, or breast, that feeds them.

The good-enough mother is one who can tolerate her infant's rage as well as her own temporary hatred of her child; she is one who is not sucked into retaliating or abandoning, and who can put aside her own self-protective responses to devote herself adequately (remember the 30 percent figure) to her child's needs. This "good enough" response, while not denying her own hatred, teaches the child that anger is something that can be survived. Winnicott wrote about how the child whose mother survives his or her destructive onslaught learns to love her as an "external" person, as an "other," not merely as an extension of themselves. This child recognizes that the mother has survived the attack and feels something on the order of joy or gratitude or relief, a dawning recognition that mother is outside his or her sphere of omnipotent control. This is the foundation of caring for her as a separate person, what we call consideration or concern or empathy.

Romantic relationships reproduce the tensions of infancy and childhood. When a patient of mine fights with her husband and he storms out of the bedroom to sleep on the couch, she becomes terrified and pursues him on hands and knees. He gets angrier and angrier and she gets more and more compliant. Unlike my friend who took care of herself in Paris after her husband had his tantrum, this patient abandons all self-respect in a futile attempt to preserve her rapport with her husband. Another patient weathers his wife's anxious and angry tirades but never quite forgives her. He is waiting for her to change, to take responsibility for the pain she is causing him, to grow. He punitively withholds kindness during the times they are not fighting, avoiding her when they could be getting along. In these marriages, nobody is surviving destruction. Rupture is never being repaired. Failures multiply and partners drift apart.

Attunement is not the problem, nor is it a myth. It is an incredible thing, as invaluable between parents and children as it is in adult intimate relationships. But an overreliance on attunement leads to disappointment and depression and division. Attunement should not have to be constant. Disruption, failure, and disagreement are healthy and normal. Learning to transition between connection and separateness without losing faith is a great challenge. In meditation, which has been essential in helping me be more accepting of the entire range of my emotional responses, I have learned to keep bringing the mind back to the central object—the breath, a prayer or a visualization—when I get distracted. But it is considered a sign of maturity in meditation when the distractions are no longer viewed as problems but can instead become objects of meditative interest in themselves. In a similar way, in intimate relationships, it is easy to view rupture as a problem to be eliminated, to see attunement as the only thing that matters: the central object, as it were. To shift one's perspective so that failures become part of the process, so that survival of destruction becomes something to celebrate, is as incredible, in its own way, as attunement. Marriage, like child rearing, is a tricky thing. You can be sailing along, satisfied that all is well, only to trip and fall when washing lettuce for the salad. Attunement is capricious; the insistence on 100 percent understanding leads only to resentment of one's partner. Marriages, like mothers, can be "good enough" while still being miracles worthy of celebration.

Attunement is not the problem, nor is it a myth. It is an incredible thing, as invaluable between parents and children as it is in adult intimate relationships. But an overreliance on attunement leads to disappointment and depression and division. Attunement should not have to be constant. Disruption, failure, and disagreement are healthy and normal. Learning to transition between connection and separateness without losing faith is a great challenge. In meditation, which has been essential in helping me be more accepting of the entire range of my emotional responses, I have learned to keep bringing the mind back to the central object—the breath, a prayer or a visualization—when I get distracted. But it is considered a sign of maturity in meditation when the distractions are no longer viewed as problems but can instead become objects of meditative interest in themselves. In a similar way, in intimate relationships, it is easy to view rupture as a problem to be eliminated, to see attunement as the only thing that matters: the central object, as it were. To shift one's perspective so that failures become part of the process, so that survival of destruction becomes something to celebrate, is as incredible, in its own way, as attunement. Marriage, like child rearing, is a tricky thing. You can be sailing along, satisfied that all is well, only to trip and fall when washing lettuce for the salad. Attunement is capricious; the insistence on 100 percent understanding leads only to resentment of one's partner. Marriages, like mothers, can be "good enough" while still being miracles worthy of celebration.