Family Guy: A Son Teaches His Father How to Grow Up

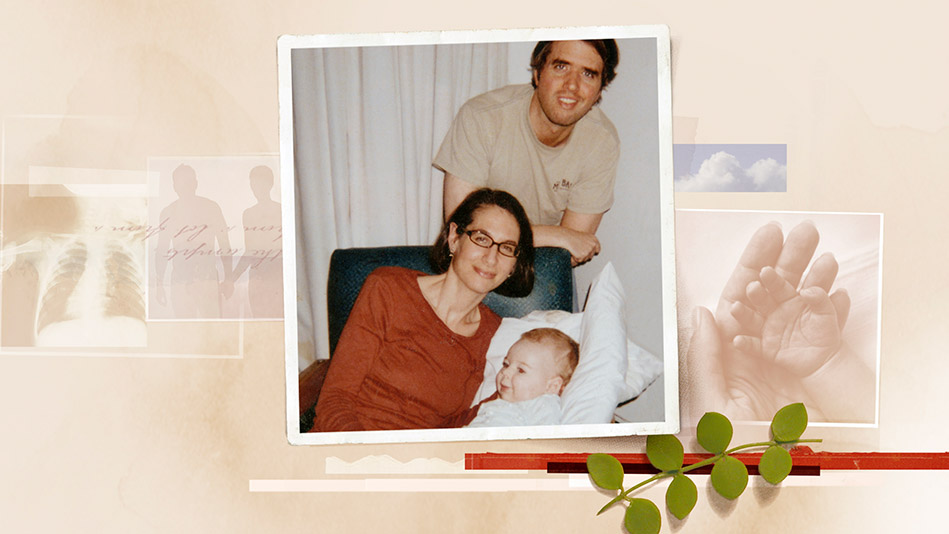

Photo: Courtesy of Hamilton Cain, Art: Cliff Alejandro

PAGE 2

The change blew in with Owen's birth in late 2002. At the age of 8 weeks, our son still couldn't hold up his head. His limbs dangled limply, like bags of sand, although his eyes tracked a penlight's beam from side to side, indicating a healthy brain. Our pediatrician pinged his knees with a rubber hammer but couldn't rouse any deep tendon reflexes. An arduous investigation ensued—clinical tests that yielded no concrete answers; X-rays and CT scans and physician consultations—culminating in a seven-month hospitalization at Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital of New York–Presbyterian in upper Manhattan. A brilliant geneticist eventually diagnosed Owen's rare disease: spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a genetic disorder that robs children of motor neuron ability. (SMA is inherited recessively; both of us carry the genetic mutation, but without any disabling symptoms.) Owen's muscles were healthy, but his nerves had failed to fully sprout, leaving him 99 percent paralyzed.

During that lengthy hospitalization, I felt cut off from all that had sustained me in my pre-Owen life, but especially from the person I felt entitled to be, that fun-seeking guy who gadded about New York. Virtually overnight I was thrown into a world of catheters and blood draws, experimental surgeries and brewing infections, hushed conversations with doctors of all stripes. Children with Owen's severe form of the disease rarely lived to their second birthday. My wife and I traded night shifts at our baby's bedside, slumped in lounge chairs, lulled into a stupor by the hospital's noises but unable to sleep. We endured weeks of further tests, frequent trips to the operating room and Owen's dangerous weight losses and suddenly plummeting oxygen levels.

One morning Ellen gently woke me in our son's hospital room after I'd spent the night there. Like an old married couple, we'd fallen into the habit of bringing each other breakfast, shoring up our listless spirits. As Ellen handed me a bagel from a paper sack, Owen began to wheeze in his bed. A mucus plug had lodged in his airway and was strangling him. The monitor shrieked as his oxygen saturation plunged, and then his heart rate: 60...40...10. He was crashing in front of us. I felt a twinge of nausea as I reached over his headboard to push the Code Blue button. In less than 30 seconds the room filled with doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists—none of whom was clear on what to do. A vortex of activity; alarms and shouts and hands at my elbow, trying to pull me away. A couple of residents trailed stethoscopes across Owen's chest, then stepped back to pronounce that there were "diminished breath sounds in his right lung."

As the confusion peaked, I grabbed the nozzle for Owen's cough-assist machine and sealed the mask against his face, while Ellen got ready to suction the sputum. We kept repeating the rhythm—one-two-three, suction, one-two-three, suction—until his oxygen levels had popped back into the normal range. The residents cheered, and our eyes locked, relieved, as though we were two basketball players who had instinctively passed to each other on the court, dribbling by the blunders of teammates to sink the Hail Mary shot.

Later, as we hovered over Owen's bed, anxiously watching each rise and fall of his diaphragm, I looked up at my wife. She was studying me, shoulders taut, eyes steely behind tortoiseshell frames, a wing of dark hair across her forehead.

"What?" I asked.

"You know it will be like this from now on," she said quietly. "Every day a minefield. There's no going back."

I ducked my chin and nodded, my whole being coiled around her words.

Gradually, as Owen stabilized, I began to comprehend—to really take in—the gravity of the situation. This was not the parenthood I'd bargained for. I'd dreamed a gauzy dream made up of Yankee games and camping trips and bicycles with training wheels, and now I was stewing in a broth of resentment and exhaustion. And that was without factoring in—because I had no way of knowing—how much more challenging the years ahead would be once Owen came home. A bevy of life-support machines. A new sleep routine, eyes half open and ears cocked for the inevitable alarm. The terrifying moments, two of them, when I saw my child rigid and blue-faced on his bed, his monitors wailing and etching out a flat line, and knew that the decisions I'd make in the next 15 seconds would determine whether he lived or died.

How do you describe that feeling to a friend, legs all rubbery and the air knocked out of you? I'd dropped down a wormhole into a weirdly distorted dimension where I was unable to locate my coordinates. There was no longer the option of whether to change. I had. Life had.

Next: How he discovered what was really important

During that lengthy hospitalization, I felt cut off from all that had sustained me in my pre-Owen life, but especially from the person I felt entitled to be, that fun-seeking guy who gadded about New York. Virtually overnight I was thrown into a world of catheters and blood draws, experimental surgeries and brewing infections, hushed conversations with doctors of all stripes. Children with Owen's severe form of the disease rarely lived to their second birthday. My wife and I traded night shifts at our baby's bedside, slumped in lounge chairs, lulled into a stupor by the hospital's noises but unable to sleep. We endured weeks of further tests, frequent trips to the operating room and Owen's dangerous weight losses and suddenly plummeting oxygen levels.

One morning Ellen gently woke me in our son's hospital room after I'd spent the night there. Like an old married couple, we'd fallen into the habit of bringing each other breakfast, shoring up our listless spirits. As Ellen handed me a bagel from a paper sack, Owen began to wheeze in his bed. A mucus plug had lodged in his airway and was strangling him. The monitor shrieked as his oxygen saturation plunged, and then his heart rate: 60...40...10. He was crashing in front of us. I felt a twinge of nausea as I reached over his headboard to push the Code Blue button. In less than 30 seconds the room filled with doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists—none of whom was clear on what to do. A vortex of activity; alarms and shouts and hands at my elbow, trying to pull me away. A couple of residents trailed stethoscopes across Owen's chest, then stepped back to pronounce that there were "diminished breath sounds in his right lung."

As the confusion peaked, I grabbed the nozzle for Owen's cough-assist machine and sealed the mask against his face, while Ellen got ready to suction the sputum. We kept repeating the rhythm—one-two-three, suction, one-two-three, suction—until his oxygen levels had popped back into the normal range. The residents cheered, and our eyes locked, relieved, as though we were two basketball players who had instinctively passed to each other on the court, dribbling by the blunders of teammates to sink the Hail Mary shot.

Later, as we hovered over Owen's bed, anxiously watching each rise and fall of his diaphragm, I looked up at my wife. She was studying me, shoulders taut, eyes steely behind tortoiseshell frames, a wing of dark hair across her forehead.

"What?" I asked.

"You know it will be like this from now on," she said quietly. "Every day a minefield. There's no going back."

I ducked my chin and nodded, my whole being coiled around her words.

Gradually, as Owen stabilized, I began to comprehend—to really take in—the gravity of the situation. This was not the parenthood I'd bargained for. I'd dreamed a gauzy dream made up of Yankee games and camping trips and bicycles with training wheels, and now I was stewing in a broth of resentment and exhaustion. And that was without factoring in—because I had no way of knowing—how much more challenging the years ahead would be once Owen came home. A bevy of life-support machines. A new sleep routine, eyes half open and ears cocked for the inevitable alarm. The terrifying moments, two of them, when I saw my child rigid and blue-faced on his bed, his monitors wailing and etching out a flat line, and knew that the decisions I'd make in the next 15 seconds would determine whether he lived or died.

How do you describe that feeling to a friend, legs all rubbery and the air knocked out of you? I'd dropped down a wormhole into a weirdly distorted dimension where I was unable to locate my coordinates. There was no longer the option of whether to change. I had. Life had.

Next: How he discovered what was really important