Oprah Goes Colonial

Oprah and Gayle arrive with gifts of ham, sugar, and cheese.

The year reenacted: 1628, when settlers arrived to eke out an existence in New England. The participants: men, women, and children—selected from nearly 10,000 applicants willing to give up beepers for bonnets—who will appear in the PBS series Colonial House, beginning May 17. The first Puritan African sojourners to pass through the colony: my (reluctant) best friend, Gayle King, and yours truly.

The year reenacted: 1628, when settlers arrived to eke out an existence in New England. The participants: men, women, and children—selected from nearly 10,000 applicants willing to give up beepers for bonnets—who will appear in the PBS series Colonial House, beginning May 17. The first Puritan African sojourners to pass through the colony: my (reluctant) best friend, Gayle King, and yours truly.

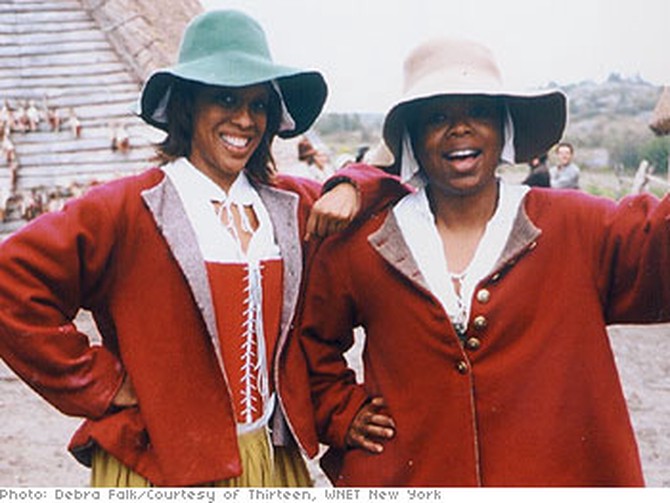

Gayle and Oprah suit up in authentic garments (including corsets).

For me, the road back to 1628 is a familiar one—it runs parallel to the outhouses, smokehouses, and farmlands of my hometown in Kosciusko, Mississippi. My grandmother and I lived on a small plot of land, in a house with no running water or toilet. I don't care how many bathrooms I've had since, I've never forgotten the outhouse. With no TV, I tried entertaining myself by making speeches to the cows and playing with my homemade corncob doll, whose hair I'd comb while longing for one with real, pretty hair. We grew everything we ate, and each morning my job was to get water from the well and feed the hogs. So how different, I thought, could Colonial House be from my own childhood? If your name is Gayle King, stunningly different. "I grew up with a toilet—and a maid," she reminds me as we land in Maine.

For me, the road back to 1628 is a familiar one—it runs parallel to the outhouses, smokehouses, and farmlands of my hometown in Kosciusko, Mississippi. My grandmother and I lived on a small plot of land, in a house with no running water or toilet. I don't care how many bathrooms I've had since, I've never forgotten the outhouse. With no TV, I tried entertaining myself by making speeches to the cows and playing with my homemade corncob doll, whose hair I'd comb while longing for one with real, pretty hair. We grew everything we ate, and each morning my job was to get water from the well and feed the hogs. So how different, I thought, could Colonial House be from my own childhood? If your name is Gayle King, stunningly different. "I grew up with a toilet—and a maid," she reminds me as we land in Maine.

Gayle stands out in a field

Aha! moment number one: Hand over the panties and bras. Seventeenth-century women didn't wear them. As we exchange our clothes for authentic garments (including uncomfortable corsets), the PBS producers present us with the settlers' codes of conduct. The Sabbath was to be strictly observed. Profanity, infidelity, promiscuity, and insurrection were punishable by whipping. Women were to obey their husbands, stay silent in public meetings, and keep their heads covered as a sign of submission. If a woman was spotted outside without her cap, she could receive a scarlet letter from the governor, then be tied to a stake for two hours. "Nobody better tie me to a stake," I whisper to Gayle, "or they are gonna see a real African Puritan." Gayle, still adjusting to pantielessness, tries not to crack up.

Aha! moment number one: Hand over the panties and bras. Seventeenth-century women didn't wear them. As we exchange our clothes for authentic garments (including uncomfortable corsets), the PBS producers present us with the settlers' codes of conduct. The Sabbath was to be strictly observed. Profanity, infidelity, promiscuity, and insurrection were punishable by whipping. Women were to obey their husbands, stay silent in public meetings, and keep their heads covered as a sign of submission. If a woman was spotted outside without her cap, she could receive a scarlet letter from the governor, then be tied to a stake for two hours. "Nobody better tie me to a stake," I whisper to Gayle, "or they are gonna see a real African Puritan." Gayle, still adjusting to pantielessness, tries not to crack up.

Oprah and Gayle with the Voorhees family

Gayle and I are given shoes that feel like they're made for two left feet ("Your feet will form to them," a producer says) as well as our roles in the story. I'm the wife of a governor, and Gayle is my widowed sister; we're passing through the colony to get herbs to take back to our ill shipmates. In exchange for the goods and a place to lodge, we bear gifts—a huge ham, some sugar, and a wheel of cheese. We're to stay with John Voorhees (in real life, a carpet salesman); his wife, Michelle Rossi-Voorhees (a seamstress who runs her own business); their 11-year-old son, Giacomo; and their dog, Chloe. In 1628 the Voorhees represent a middle-class family who sailed here from England to create a new life.

Gayle and I are given shoes that feel like they're made for two left feet ("Your feet will form to them," a producer says) as well as our roles in the story. I'm the wife of a governor, and Gayle is my widowed sister; we're passing through the colony to get herbs to take back to our ill shipmates. In exchange for the goods and a place to lodge, we bear gifts—a huge ham, some sugar, and a wheel of cheese. We're to stay with John Voorhees (in real life, a carpet salesman); his wife, Michelle Rossi-Voorhees (a seamstress who runs her own business); their 11-year-old son, Giacomo; and their dog, Chloe. In 1628 the Voorhees represent a middle-class family who sailed here from England to create a new life.

Gayle chops wood with colonist Jonathon Allen

As the Voorhees thank us profusely for the ham, sugar, and cheese ("You saved us!" they keep saying) and show us to their one-room cabin, they fill us in on the daily challenges: Endless wood chopping. Sparse food. Isolation. Fear of wild animals. Filthy clothing. "It's amazing how what may initially seem like an utterly desperate existence can seamlessly morph into a surprisingly tolerable way of life," Julia Friese, who took a leave from her job at a children's museum in Philadelphia, later says of her role as an indentured servant. "Bathing once a week, at most, and sanitation standards that would make even a fraternity boy blush all become just normal."

As the Voorhees thank us profusely for the ham, sugar, and cheese ("You saved us!" they keep saying) and show us to their one-room cabin, they fill us in on the daily challenges: Endless wood chopping. Sparse food. Isolation. Fear of wild animals. Filthy clothing. "It's amazing how what may initially seem like an utterly desperate existence can seamlessly morph into a surprisingly tolerable way of life," Julia Friese, who took a leave from her job at a children's museum in Philadelphia, later says of her role as an indentured servant. "Bathing once a week, at most, and sanitation standards that would make even a fraternity boy blush all become just normal."

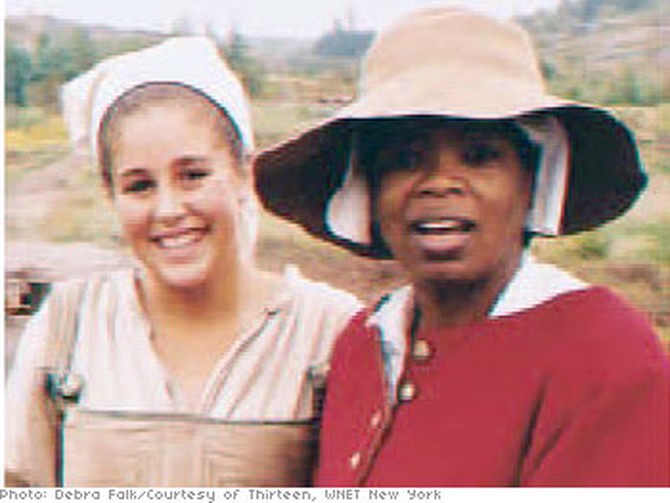

With fellow egg-gatherer Maddison Verdecia

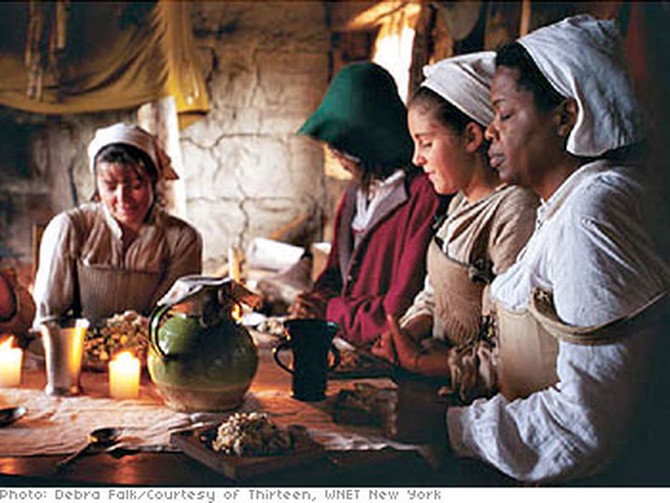

Each day the women cook with a fistful of scarce ingredients: eggs, flour, sugar, rice, and vegetables they've planted. Over an open fire that has been burning since daybreak (in the 1600s, it was a woman's job to keep the fire going), we roast the fresh green beans and carrots we picked. I chop wood and gather eggs from the henhouse (did I say I'd done this before?), and Gayle milks a goat—the perfect job for someone who, having never been a drinker, is known to ask a bartender, "Got milk?" Later we eat our meal with crudely shaped spoons. In 1628 commoners didn't use forks.

Each day the women cook with a fistful of scarce ingredients: eggs, flour, sugar, rice, and vegetables they've planted. Over an open fire that has been burning since daybreak (in the 1600s, it was a woman's job to keep the fire going), we roast the fresh green beans and carrots we picked. I chop wood and gather eggs from the henhouse (did I say I'd done this before?), and Gayle milks a goat—the perfect job for someone who, having never been a drinker, is known to ask a bartender, "Got milk?" Later we eat our meal with crudely shaped spoons. In 1628 commoners didn't use forks.

With Don Wood, Dominic Muir, and Henry the dog

Nighttime brings a "colonial jamboree"—yippee yi yo. To kick things off, the women line up across from the men for a dance—two steps up, two steps back, then lift and swing your partner. Have you ever tried to lift and swing a braless, 5'10" black woman? Apparently, Gayle's partner hadn't, either. He hoisted her into the air and landed her on her backside, feet heavenward.

Nighttime brings a "colonial jamboree"—yippee yi yo. To kick things off, the women line up across from the men for a dance—two steps up, two steps back, then lift and swing your partner. Have you ever tried to lift and swing a braless, 5'10" black woman? Apparently, Gayle's partner hadn't, either. He hoisted her into the air and landed her on her backside, feet heavenward.

Dinner with one of the colonial families. On the menu is a mash of field peas.

As for our accommodations, I wasn't anticipating the Four Seasons, but I also had no idea that I'd be sharing a loft with Gayle and Giacomo. After the three of us mount the rickety ladder to our individual mattresses, we're in for the night—a night so dark that I can close my eyes and open them again to see the same pitch-black. Without a watch, my only reference to time is my body's internal clock: For years I've always awakened to use the bathroom between 3:15 and 3:30 a.m. When I get up for my early morning squat in the bushes, Gayle—who has been holding it for hours because she's too scared to make her way down that ladder alone in the dark—braves the climb and the rain with me. Back in the loft, I whisper to Gayle, "Don't you just love the sound of the rain?" "No, I don't," she groans, still annoyed because she forgot to take her "toilet paper"—a big leaf—with her. "Did you hear little feet scurrying?" she asks. "That's just Chloe, the dog," I say. "So Chloe is up on the roof?" she shoots back. "If a mouse drops in from the ceiling," I say, "it's over for me." We snicker, trying not to wake up Mom and Dad Voorhees below, and give in to restless sleep again…until the cockle-doodle-dooing begins.

As for our accommodations, I wasn't anticipating the Four Seasons, but I also had no idea that I'd be sharing a loft with Gayle and Giacomo. After the three of us mount the rickety ladder to our individual mattresses, we're in for the night—a night so dark that I can close my eyes and open them again to see the same pitch-black. Without a watch, my only reference to time is my body's internal clock: For years I've always awakened to use the bathroom between 3:15 and 3:30 a.m. When I get up for my early morning squat in the bushes, Gayle—who has been holding it for hours because she's too scared to make her way down that ladder alone in the dark—braves the climb and the rain with me. Back in the loft, I whisper to Gayle, "Don't you just love the sound of the rain?" "No, I don't," she groans, still annoyed because she forgot to take her "toilet paper"—a big leaf—with her. "Did you hear little feet scurrying?" she asks. "That's just Chloe, the dog," I say. "So Chloe is up on the roof?" she shoots back. "If a mouse drops in from the ceiling," I say, "it's over for me." We snicker, trying not to wake up Mom and Dad Voorhees below, and give in to restless sleep again…until the cockle-doodle-dooing begins.

With the Verdecia family.

It's Sunday morning, and Gayle and I arrive at church (in the same clothes) for a service filled with traditional hymns and a brief sermon about the spirit of community. There's been trouble in the colony surrounding the church requirement: One family resisted being forced to go and was verbally reprimanded by the minister—a punishment surely less harsh than a real settler would have received.

It's Sunday morning, and Gayle and I arrive at church (in the same clothes) for a service filled with traditional hymns and a brief sermon about the spirit of community. There's been trouble in the colony surrounding the church requirement: One family resisted being forced to go and was verbally reprimanded by the minister—a punishment surely less harsh than a real settler would have received.

Tending to the garden.

For five months, the lay preacher's wife, Carolyn Heinz—whose real job is anthropology professor—had the challenge of avoiding upsets over the strict codes that made women voiceless. "Being a 17th-century colonist was possibly the hardest time of my life," she said after filming ended. "It will always be a part of me—a brief, tough stretching of my imagination back to my ancestors' experience of the New World." Dominic Muir, a private tutor from London who served as a quartermaster, said, "I witnessed the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity, the power of prayer, being so happy with such little stuff—and finding log fires better to watch than television. I felt close to God—and close to peas and oats. It was humbling and fantastic, and I miss it." Back home in California, Carolyn, the preacher's wife, can't quite use the word miss. She says, "I'm glad I did it—and I'm glad it's over."

For five months, the lay preacher's wife, Carolyn Heinz—whose real job is anthropology professor—had the challenge of avoiding upsets over the strict codes that made women voiceless. "Being a 17th-century colonist was possibly the hardest time of my life," she said after filming ended. "It will always be a part of me—a brief, tough stretching of my imagination back to my ancestors' experience of the New World." Dominic Muir, a private tutor from London who served as a quartermaster, said, "I witnessed the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity, the power of prayer, being so happy with such little stuff—and finding log fires better to watch than television. I felt close to God—and close to peas and oats. It was humbling and fantastic, and I miss it." Back home in California, Carolyn, the preacher's wife, can't quite use the word miss. She says, "I'm glad I did it—and I'm glad it's over."

Baking flatbread, which accompanies most meals.

Me, too, Carolyn—after even less than two days. "We don't have to stay another night, do we?" Gayle asks after church. Our hair still smelling of smoke, we head home, more appreciative than ever of all the luxuries we sometimes overlook—and giving thanks for all the shoulders we stand upon. None of us can store food in a freezer, turn on a stove, fill up a gas tank, or soak in a bathtub without that recognition. We are who we are because someone brave walked before us.

Me, too, Carolyn—after even less than two days. "We don't have to stay another night, do we?" Gayle asks after church. Our hair still smelling of smoke, we head home, more appreciative than ever of all the luxuries we sometimes overlook—and giving thanks for all the shoulders we stand upon. None of us can store food in a freezer, turn on a stove, fill up a gas tank, or soak in a bathtub without that recognition. We are who we are because someone brave walked before us.

Posing with the families.

Could you and I have survived in 1628? Sure. But the miracle is that we don't have to. Some other courageous woman already did. It is on that woman's behalf—a woman silenced by the edicts of her time—that we can speak. We can disagree. We can build, we can choose, we can own ourselves. And more than 300 years after the first colonists sailed in, we can choose whether to go to church or not, we can worship as we please—or we can lounge in bed on a Sunday morning, wearing the very cutest underwear.

Could you and I have survived in 1628? Sure. But the miracle is that we don't have to. Some other courageous woman already did. It is on that woman's behalf—a woman silenced by the edicts of her time—that we can speak. We can disagree. We can build, we can choose, we can own ourselves. And more than 300 years after the first colonists sailed in, we can choose whether to go to church or not, we can worship as we please—or we can lounge in bed on a Sunday morning, wearing the very cutest underwear.

From the June 2004 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine