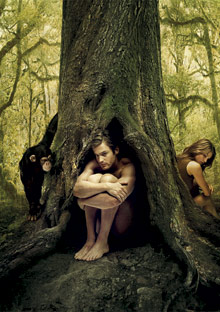

Photo Illustration: Jonathan Barkat

They came from wildly different backgrounds, and for 21 years, they've fought over politics, history, dish washing techniques, how to cook chicken...and yet, it works.

When a friend called and asked if I wanted to meet a recently divorced man she knew, I asked, "Who is he?" and listened attentively. I had been separated from my husband for a few years and missed the company of men. She listed this one's impressive accomplishments: a psychiatrist with a degree in comparative literature, and a good man, she said. She added somewhat tentatively, "And I think he's Jewish."

I said, "Oh, that's absolutely fine with me."

I am an Anglican, born in South Africa, where I attended a church school as a child. In America I found great comfort in the Episcopal Church, singing the hymns and saying the prayers from my childhood. I consider myself a Christian and try to live as one. I grew up under apartheid and had suffered with prejudice of every kind around me for long enough. Had my mother not told me she would rather I married a Jew than a Catholic? Was not Jesus a Jew? Besides, if anything, surely it was the Jews who were the superior people. Were they not the great thinkers, the artists, the scientists? What about Freud, Yehudi Menuhin, Isaac Stern, and Einstein?

Of course I wanted to meet her accomplished friend. I was extremely eager to meet him and fall in love with—ah, yes! A Jew.

And we did meet, in a Japanese restaurant, and over the course of the meal and, later, coffee at his house, I did fall in love with the man who sat opposite me. I fell for the shock of white hair, the large, melancholy eyes, the aquiline nose, the smooth skin, and the boyish, slim hips. Above all, I fell for his mind, all the poetry he knew by heart: Wordsworth, which I had read as a child; Blake; and, of course, Heine, which he could quote in German. I discovered he had read the books I'd read, loved, and tried to emulate. He knew Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Flaubert.

How could I resist? Moreover, how could I resist the way he let his hand hover so lovingly on his son's head, the way he carried my suitcase to the station, brought me breakfast in bed when I had a cold, or rose in the night with my daughter's first baby to walk the child in the steamy bathroom to help with her cold, the way he held me in the night when I couldn't sleep. I fell in love with the way he walked me across the park to the church I attended and stood on the steps, waving me goodbye with a gentle, approving smile.

This time, we both said, we had found the right mate, not the boy or girl next door but someone strange and different, someone other, someone to love and cherish until death would us part.

We found a jovial gay Lutheran minister to marry us in our apartment in Greenwich Village. We took him out to dinner, and after a few glasses of wine and a heaping plate of stew, when I gently suggested it might not be necessary to mention Jesus too often during the ceremony, he nodded understandingly. We had all our five children read poetry and my new husband's father, a tall and elegant man, recite a prayer in Hebrew. At the end of the ceremony, I insisted that my husband break a glass in what I considered customary Jewish fashion. All went off splendidly, surrounded by our friends and family and some excellent French caterers, although, afterward, my husband's father gently took me aside and whispered in my ear that the breaking of the glass in his Reformed tradition was considered going a bit too far with tradition.

Photo: Courtesy of Sheila Kohler

After that, well, the years went by. We made love frequently, we worked, and we fought. We fought with good intentions, good humor, many laughs, and mostly in the kitchen—strangely, or was it?—over food, but still we fought. I, who prided myself on my cooking—had I not done a course in Paris at the Cordon Bleu, had I not been praised by my first husband for my cooking?—was told to put the chicken back in the oven. "It's still squawking!" my husband told me. I wanted the steak rare, he wanted it well done; I wanted my vegetables soggy, he wanted them crunchy.

We fought over who would do the dishes and how they would be done: He wanted to wash them by hand; I wanted to put them in the dishwasher. We fought over what food to buy. I wanted to fill the refrigerator in one fell swoop with expensive prosciutto, leg of lamb, and runny brie from Balducci's. He wanted to go daily to Fairway to look for heart- and purse-saving bargains: no egg yolks, no fatty cheeses, no bacon fat for cooking the French toast. "Do you want to clog your arteries? One egg has the cholesterol of a tub of butter!" he exclaimed.

"Can you never screw the top on a bottle!" he shouted at me, taking out the orange juice with its loose cap and watching it splash, once again, all over the floor.

We fought over feelings: Why did he not express his more freely? Why was he often silent? What was he thinking about? Why didn't or couldn't he tell me? Why wasn't he the one to say "I love you" over and over again? How could he criticize my work—much of which I brought him to read in early stages—so harshly. "In English we say...," he would exclaim, rewriting one of my sentences.

We fought over politics. Yes, the Holocaust was unspeakable, but there had been other crimes against humanity, surely. My own South African family had come originally from a small town in Bavaria, as did some of the worst Nazis. Yes, the Germans had behaved unbelievably, but were the Americans so very perfect?

What about slavery? What about the American Indians? What about the war in Iraq? Did he always have to dump on the Christians? Should we not cast the mote from our own eye, as I had been taught? Did the six million dead Jews have to come up quite so frequently?

"How can you be so stiff-necked!" I shouted at him one morning in the kitchen over breakfast, while he drank his tea and I, my coffee.

"That's what they have been calling my people for 2,000 years," he said, looking at me askance. Worse still, in a moment of rage on holiday in Italy, hungry, hot, and tired, tramping through the street with sore feet and wanting to enter some expensive eating place, while he sought something more modest, I found myself shouting at him, "You're just a stingy Jew!"

And he, when I had asked once again for the driving directions to my daughter's house, which I had visited many times, exclaimed that all that pork-eating must have gone to my head!

Had I married a racist? Worse still, had I discovered that in my heart of hearts I was a racist? Were people then not all the same, after all? Were men and women so very different? Were Jews and Christians incompatible?

My friend who had introduced us had lunch with me one day. We'd been married a few years by then.

"Happy?" she asked, smiling proudly at the thought of her handiwork.

We fought over who would do the dishes and how they would be done: He wanted to wash them by hand; I wanted to put them in the dishwasher. We fought over what food to buy. I wanted to fill the refrigerator in one fell swoop with expensive prosciutto, leg of lamb, and runny brie from Balducci's. He wanted to go daily to Fairway to look for heart- and purse-saving bargains: no egg yolks, no fatty cheeses, no bacon fat for cooking the French toast. "Do you want to clog your arteries? One egg has the cholesterol of a tub of butter!" he exclaimed.

"Can you never screw the top on a bottle!" he shouted at me, taking out the orange juice with its loose cap and watching it splash, once again, all over the floor.

We fought over feelings: Why did he not express his more freely? Why was he often silent? What was he thinking about? Why didn't or couldn't he tell me? Why wasn't he the one to say "I love you" over and over again? How could he criticize my work—much of which I brought him to read in early stages—so harshly. "In English we say...," he would exclaim, rewriting one of my sentences.

We fought over politics. Yes, the Holocaust was unspeakable, but there had been other crimes against humanity, surely. My own South African family had come originally from a small town in Bavaria, as did some of the worst Nazis. Yes, the Germans had behaved unbelievably, but were the Americans so very perfect?

What about slavery? What about the American Indians? What about the war in Iraq? Did he always have to dump on the Christians? Should we not cast the mote from our own eye, as I had been taught? Did the six million dead Jews have to come up quite so frequently?

"How can you be so stiff-necked!" I shouted at him one morning in the kitchen over breakfast, while he drank his tea and I, my coffee.

"That's what they have been calling my people for 2,000 years," he said, looking at me askance. Worse still, in a moment of rage on holiday in Italy, hungry, hot, and tired, tramping through the street with sore feet and wanting to enter some expensive eating place, while he sought something more modest, I found myself shouting at him, "You're just a stingy Jew!"

And he, when I had asked once again for the driving directions to my daughter's house, which I had visited many times, exclaimed that all that pork-eating must have gone to my head!

Had I married a racist? Worse still, had I discovered that in my heart of hearts I was a racist? Were people then not all the same, after all? Were men and women so very different? Were Jews and Christians incompatible?

My friend who had introduced us had lunch with me one day. We'd been married a few years by then.

"Happy?" she asked, smiling proudly at the thought of her handiwork.

"He's a good, a wonderful man, just as you said," I gushed, but something in my face must have belied my words.

"So what's the problem?" she asked.

"He won't let me do the dishes or cook the steak. And he never says he loves me," I said. She looked at me, appalled. She said, "You want to do the dishes? You want to cook the steak? I thought you had enough of that with your first husband."

"Well, yes," I admitted, "but after all, food is such an important part of life. When all is said and done, the kitchen is the woman's domain, the place where, surely, she should have at least a say in how things are done. Now she doesn't have any domain at all."

"You have your work, your books. You have published—how many books since you were married? What have we women's libbers been fighting for, then?" she asked me, banging her fist on the checkered cloth. "Why don't you just let him do the dishes if he wants to? Let him cook his steak the way he likes it. A little distance, perhaps, is required?"

Indeed, I thought just this weekend as I watched my husband, now of many years, this white-haired American Jew, sitting beside me in the car, as he drove me home through blinding rain after taking me to read from a new book in some place upstate, a reading he himself had organized for me and then sat through, as I attempted to peddle my wares.

"What could I write about for O magazine?" I asked him, to the sound of the windshield wipers beating back and forth, the whine of the tires on the road.

"What about writing about a marriage between a Jew and a Christian?" he asked, turning his head and half smiling at me, adding, "You know something about that, I think?"

"Perhaps," I said, and added, "I could even find a happy ending to the piece," reaching out for his most beloved of hands.

Read more relationship stories in Love, the Great Adventure

"So what's the problem?" she asked.

"He won't let me do the dishes or cook the steak. And he never says he loves me," I said. She looked at me, appalled. She said, "You want to do the dishes? You want to cook the steak? I thought you had enough of that with your first husband."

"Well, yes," I admitted, "but after all, food is such an important part of life. When all is said and done, the kitchen is the woman's domain, the place where, surely, she should have at least a say in how things are done. Now she doesn't have any domain at all."

"You have your work, your books. You have published—how many books since you were married? What have we women's libbers been fighting for, then?" she asked me, banging her fist on the checkered cloth. "Why don't you just let him do the dishes if he wants to? Let him cook his steak the way he likes it. A little distance, perhaps, is required?"

Indeed, I thought just this weekend as I watched my husband, now of many years, this white-haired American Jew, sitting beside me in the car, as he drove me home through blinding rain after taking me to read from a new book in some place upstate, a reading he himself had organized for me and then sat through, as I attempted to peddle my wares.

"What could I write about for O magazine?" I asked him, to the sound of the windshield wipers beating back and forth, the whine of the tires on the road.

"What about writing about a marriage between a Jew and a Christian?" he asked, turning his head and half smiling at me, adding, "You know something about that, I think?"

"Perhaps," I said, and added, "I could even find a happy ending to the piece," reaching out for his most beloved of hands.

Read more relationship stories in Love, the Great Adventure