Illustration: David Cowles

Barricaded in his room, listening to the Fab Four—over and over and over— Jim Shepard's brother was an enigma, a challenge, an occasional terror. How do you come to terms with someone like that? With tenderness, clarity, and a little help from a distant volcano.

The British wave hit America in late December 1963 and funneled ashore, at least on the East Coast, principally through two New York AM radio stations: WMCA, the Good Guys—Joe O'Brien, Harry Harrison, Jack Spector, Gary Stevens, and Dandy Dan Daniel—and WABC, with Bruce Morrow, or as he called himself, Cousin Brucie. My brother listened to every one of them. The Beatles' first American single—"I Want to Hold Your Hand," with "I Saw Her Standing There" on the B side—traveled from outside our consciousness to number one in the country in about 30 minutes, and my brother had the 45 and was playing it in his room 35 minutes after that. At that point he was 12 and I was 7. He was not yet entirely withdrawn from socializing—he had one or two good friends who occasionally came over and listened to music or, much more rarely, tossed around a baseball or football in the yard—but for the most part I experienced him as a shut door from behind which issued all sorts of excited radio chatter, and music. The most common conversation I had with my parents in those years involved one of them asking, with an understated and anticipatory dismay, "Where's your brother?" and my having to answer, "In his room." My brother as a mystery; my brother as a shut door: Those are some of the first and primary ways I experienced him, and it always seemed, in that sibling way, that he had a right to erect barriers, and that it was my job to get over them. Whenever I opened his door and wandered in—something I'd do periodically, intrigued by the music or just wanting more access to him—he'd go on with what he was doing for a few minutes as a way of suffering my presence and allowing me what I wanted, before finally asking, "Can I help you?"

Sometimes I'd say no and head back out. At other times I'd sit on his bed and he'd say, "Don't you have something you're supposed to be doing?"

To extend the conversation I'd usually ask a question to which I knew he knew the answer. We'd have exchanges like this:

"What time's Daddy going out?"

"I don't know."

"I thought you said he was going out at 10."

"If you knew that, why're you bothering me?"

That February he turned 13. He'd prohibited birthday parties in his honor since he'd been a toddler, but he took his birthday money—maybe $20 from our parents, and another $10 from our grandparents—and converted it into English rock 'n' roll: at 79 cents a pop, probably some forty 45s. That summer I remember he went through a dark period in which he was pretty much only in his room listening to music, and I'd come back from the beach or wherever and peer at his door. I made top-ten lists at my desk of my favorites of his new records and changed them daily. Sometimes I poked his door open because I had to identify a new song, or to ask him how to spell a band like Manfred Mann, but mostly I left him alone. I had my own things going on.

But one day I didn't. I missed him. I went up to his door and between songs asked if he wanted something to eat. He said he didn't. I asked if he wanted something to drink. He said no again.

I listened to a few more songs and then opened his door and wandered in. In the best of times, these weren't visits he welcomed, and these weren't the best of times, though I wasn't sure why. I stood there, concerned and committed to trying to brazen it out, and he sat with his back to me for as long as he could stand it and then finally turned around. He looked unhappier than even I would have expected a 13-year-old could look.

And while he watched, I started bouncing on one leg and drawing the other knee up to my chest, and then bouncing on the other.

"What're you doing?" he asked.

"Is this how you do the Pony?" I asked back.

He kept looking at me until I stopped. "Get away from me," he said.

Jim Shepard (in the carriage), with John; 1956.

As part of their attempt to do as much as they could for him, my parents had taken him out of the public school and enrolled him in a parochial school—Blessed Sacrament, in Bridgeport—and the latter was one of those nightmares that inner-city parochial schools could be in those days. The nicer nuns hit you with an open hand instead of a fist or an object. Any kind of nonconformity or questioning was evidence that you were a wise guy and looking for some correction. Any type of levity was evidence of the same thing. It was the sort of place in which detention consisted not of staying after school but coming back to the school at 7 A.M. Saturday morning to spend the day doing janitorial work: bleaching the sinks, mopping the floors, washing the windows.

To say my brother detested it there really didn't capture the desperation, the extremity, of his misery. My parents had already paid what they thought was a lot of money for this education and were also of the generation that thought you didn't take a kid out of a school just because he said he didn't like it. Who liked anything they were doing?

He had very few friends at Blessed Sacrament and was rarely able to play with them, since most lived all the way across town. He withdrew even more. When he graduated, he was allowed to enroll in our local pit of a public high school—my parents having conceded that maybe parochial school wasn't the thing for him—but arrived at Stratford High just as its administration had decided to draw its line in the sand when it came to the culture wars. My brother by that point had what was called long hair—and by that I mean he looked like Ringo Starr in A Hard Day's Night, with bangs that obscured part of his forehead and hair over the tops of his ears—and there was a rule about that at Stratford High. My brother would be told to get his hair cut and would head off to the barber's and ask for the most infinitesimal of trims. Back at school the principal would say, "I thought I told you to get your hair cut," and my brother would say he had. And the principal in retaliation would do things like make my brother stand up in the middle of assembly—this is in a group of 3,000—and show everyone his hair. Or he'd send my brother home in the middle of the day: a five-mile walk.

Eventually, my brother dropped out. He refused to get a job, or, rather, he got all sorts of jobs and then had to quit them. By then he had a supernaturally heightened sense of humiliation, and any kind of remark, however well meaning—like a coworker's question along the lines of "What's somebody like you doing working here?"—would ensure that he never came back.

Which led to a frustration level so high that he had periodic explosions. I knew enough to keep away from him at such times, but we were good at baiting each other, so I didn't always try. Once he threw me over a sofa with enough brio that my back impacted the wall. Another time he pitched me down the stairs.

To say my brother detested it there really didn't capture the desperation, the extremity, of his misery. My parents had already paid what they thought was a lot of money for this education and were also of the generation that thought you didn't take a kid out of a school just because he said he didn't like it. Who liked anything they were doing?

He had very few friends at Blessed Sacrament and was rarely able to play with them, since most lived all the way across town. He withdrew even more. When he graduated, he was allowed to enroll in our local pit of a public high school—my parents having conceded that maybe parochial school wasn't the thing for him—but arrived at Stratford High just as its administration had decided to draw its line in the sand when it came to the culture wars. My brother by that point had what was called long hair—and by that I mean he looked like Ringo Starr in A Hard Day's Night, with bangs that obscured part of his forehead and hair over the tops of his ears—and there was a rule about that at Stratford High. My brother would be told to get his hair cut and would head off to the barber's and ask for the most infinitesimal of trims. Back at school the principal would say, "I thought I told you to get your hair cut," and my brother would say he had. And the principal in retaliation would do things like make my brother stand up in the middle of assembly—this is in a group of 3,000—and show everyone his hair. Or he'd send my brother home in the middle of the day: a five-mile walk.

Eventually, my brother dropped out. He refused to get a job, or, rather, he got all sorts of jobs and then had to quit them. By then he had a supernaturally heightened sense of humiliation, and any kind of remark, however well meaning—like a coworker's question along the lines of "What's somebody like you doing working here?"—would ensure that he never came back.

Which led to a frustration level so high that he had periodic explosions. I knew enough to keep away from him at such times, but we were good at baiting each other, so I didn't always try. Once he threw me over a sofa with enough brio that my back impacted the wall. Another time he pitched me down the stairs.

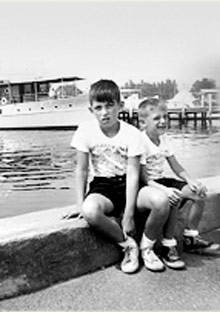

Jim (right), age 6, with John in 1963.

My parents tried group therapy. They tried individual sessions with psychiatrists. They finally enrolled him in what they hoped was an innovative experimental program, but as far as he was concerned, he was being institutionalized at 16. He wasn't released until eight months later.

The hospital was Yale–New Haven, a teaching hospital, and they either didn't have much of an idea of what to do with him or were totally at a loss, depending on which doctor you talked to. We visited him every week and every week he wept and pleaded with us to take him home. And every week we said no, because the doctors told us he needed to stay. Even as they also were telling us that he was remarkably resistant to any sort of treatment.

Since it was a teaching hospital, and nothing was working, and this was the dawn of time when it came to psychopharmaceuticals, they also tried all sorts of new products on him. Some had humiliating side effects. None worked.He was by then 18 or 19 and had, as he liked to put it, his whole fucking life ahead of him. He moved back home. He still had his music, but he also had his rage with it. He sat up in his room most of the day like an unexploded bomb.

As a family it consumed us, and at the same time we became expert at not discussing it. My parents couldn't bring him up without lashing out at each other—since they'd always had diametrically opposed ideas of what would help, and they each thought that time was wasting—and his condition seemed both so ineffable and intractable that none of us knew how to articulate it to anyone outside the family. He always came off sounding either shiftless or oblique.

I traded on stories about him sometimes—but mostly I didn't. In college every so often a casual friend might say, a few months into our acquaintance, that he hadn't realized I had a brother. I'd give him some details and then get to that point of having to decide whether or not to open the whole can of worms. Usually I'd opt for the shorter version.

When I first started seriously writing fiction, he never came up. My first novel, which was directly autobiographical, featured everybody important to my life except him. (Though I did give my protagonist a younger sister who displayed some of the same worrisome issues.) As varied as my fiction got, though, for the next 11 years, the one thing that was consistent about it was its refusal to engage, except in covert ways, the single most fraught aspect of my family's history.

The hospital was Yale–New Haven, a teaching hospital, and they either didn't have much of an idea of what to do with him or were totally at a loss, depending on which doctor you talked to. We visited him every week and every week he wept and pleaded with us to take him home. And every week we said no, because the doctors told us he needed to stay. Even as they also were telling us that he was remarkably resistant to any sort of treatment.

Since it was a teaching hospital, and nothing was working, and this was the dawn of time when it came to psychopharmaceuticals, they also tried all sorts of new products on him. Some had humiliating side effects. None worked.He was by then 18 or 19 and had, as he liked to put it, his whole fucking life ahead of him. He moved back home. He still had his music, but he also had his rage with it. He sat up in his room most of the day like an unexploded bomb.

As a family it consumed us, and at the same time we became expert at not discussing it. My parents couldn't bring him up without lashing out at each other—since they'd always had diametrically opposed ideas of what would help, and they each thought that time was wasting—and his condition seemed both so ineffable and intractable that none of us knew how to articulate it to anyone outside the family. He always came off sounding either shiftless or oblique.

I traded on stories about him sometimes—but mostly I didn't. In college every so often a casual friend might say, a few months into our acquaintance, that he hadn't realized I had a brother. I'd give him some details and then get to that point of having to decide whether or not to open the whole can of worms. Usually I'd opt for the shorter version.

When I first started seriously writing fiction, he never came up. My first novel, which was directly autobiographical, featured everybody important to my life except him. (Though I did give my protagonist a younger sister who displayed some of the same worrisome issues.) As varied as my fiction got, though, for the next 11 years, the one thing that was consistent about it was its refusal to engage, except in covert ways, the single most fraught aspect of my family's history.

The Shepard boys; 1964.

I tried to think of it as an admirable restraint. Some of that restraint, after all, had to do with my desire to protect their privacy. More of it had to do with my fear that I couldn't handle the material. And some had to do with my impatience with the way autobiographical fiction often seemed designed to exonerate, confessing to what we suspected was the lesser crime in order to divert attention from even more massive failures, and offering with a kind of a wheedle a pathetic determinism in the form of past injustices that explained present character flaws.

But I also knew that eventually I would deal with that subject. How could I not? And that the attempt to work through that kind of suffering, on all our parts, depending on the emotional honesty with which it was approached, could proceed from the exploitative to the redemptive. I finally found myself doing so the way my family did everything: through the back door.

My whole life, I've had an obsession with tidal waves. Tidal waves used to cruise through my dreams on the average of once a month. Tidal waves were a subject I could never turn away from. Tidal waves turned out to be, I discovered, a difficult thing to work into serious fiction. I gave it a shot at the end of my third novel, if only in my protagonist's imagination.

But I wanted to write about a real tidal wave. And those of us who are obsessive tsunami fanatics prick up our ears at almost any mention of Krakatoa, the volcanic island in Indonesia that annihilated itself so spectacularly in 1883. I mean, come on: 300-foot waves storming in out of the ash-choked darkness with such appalling majesty that survivors from high ground first registered them as far-off mountain ranges that seemed to be moving. Over the years I read everything I could about what they were like, what they might have been like, what happened on Krakatoa.

And of course I wanted to write fiction about it. Maybe something historical? But I wasn't so far gone that I aspired to a cheesy literary version of Krakatoa, East of Java. So I had to ask myself what I asked my students: What about the subject was in any way fraught for me? What about it transcended what would otherwise be just your typical small boy's mesmerized fascination with a particular kind of catastrophe?

I began to feel as though my brother was somehow involved in the project. Thoughts about one led me to thoughts about the other. Though the metaphoric connections that suggested themselves at first seemed reductive and simplistic.

Then it occurred to me that the link I was seeking involved that very urge to reduce and simplify causality, when it came to dealing with catastrophe. That maybe picking over the bombed-out ruins of familial dysfunction was analogous to investigating the causes of great volcanic eruptions. In both cases, we're dealing with braided events: not single motives or causes but a constellation of interlocking constellations, a situation in which each system is conditioned by and conditions others. The jaw-dropping tsunamis that fanned out from Krakatoa in 1883 turned out not to have been generated by any single geologic factor but by a massive interlocking system of events: one that could be picked apart with care and appalled fascination, but also one that would never offer up all of its mysteries.

But I also knew that eventually I would deal with that subject. How could I not? And that the attempt to work through that kind of suffering, on all our parts, depending on the emotional honesty with which it was approached, could proceed from the exploitative to the redemptive. I finally found myself doing so the way my family did everything: through the back door.

My whole life, I've had an obsession with tidal waves. Tidal waves used to cruise through my dreams on the average of once a month. Tidal waves were a subject I could never turn away from. Tidal waves turned out to be, I discovered, a difficult thing to work into serious fiction. I gave it a shot at the end of my third novel, if only in my protagonist's imagination.

But I wanted to write about a real tidal wave. And those of us who are obsessive tsunami fanatics prick up our ears at almost any mention of Krakatoa, the volcanic island in Indonesia that annihilated itself so spectacularly in 1883. I mean, come on: 300-foot waves storming in out of the ash-choked darkness with such appalling majesty that survivors from high ground first registered them as far-off mountain ranges that seemed to be moving. Over the years I read everything I could about what they were like, what they might have been like, what happened on Krakatoa.

And of course I wanted to write fiction about it. Maybe something historical? But I wasn't so far gone that I aspired to a cheesy literary version of Krakatoa, East of Java. So I had to ask myself what I asked my students: What about the subject was in any way fraught for me? What about it transcended what would otherwise be just your typical small boy's mesmerized fascination with a particular kind of catastrophe?

I began to feel as though my brother was somehow involved in the project. Thoughts about one led me to thoughts about the other. Though the metaphoric connections that suggested themselves at first seemed reductive and simplistic.

Then it occurred to me that the link I was seeking involved that very urge to reduce and simplify causality, when it came to dealing with catastrophe. That maybe picking over the bombed-out ruins of familial dysfunction was analogous to investigating the causes of great volcanic eruptions. In both cases, we're dealing with braided events: not single motives or causes but a constellation of interlocking constellations, a situation in which each system is conditioned by and conditions others. The jaw-dropping tsunamis that fanned out from Krakatoa in 1883 turned out not to have been generated by any single geologic factor but by a massive interlocking system of events: one that could be picked apart with care and appalled fascination, but also one that would never offer up all of its mysteries.

With that understanding, and that as a shadowy thematic premise, I had my parallel narrative tracks. My protagonist was a vulcanologist studying the eruption at Krakatoa. His brother was the eruptive event in his own history that so complicated the nature of his curiosity. It only remained for me to make sure that the analogy was an analogy that broke down nearly as often as it proved useful; that it continually complicated itself and enlarged its implications.

And I was liberated in dramatic and aesthetic terms by reminding myself that fiction didn't necessarily become autobiography because some of its elements—even crucial elements—were autobiographical. I wasn't engaged in replication but in new construction. William Gass once in an essay compared memories to balloons into which the past has been breathed, which implies that fiction might be seen as the twisting that creates balloon animals of pleasing, or silly, or moving shapes.

And writing about just how agonized my brother had been, and how much I'd felt like I'd let him down, led me to other kinds of solace as well, as one kind of memory unsheathed another. Just as walking through this account has allowed me to peep around other corners, and to continue to reeducate myself.

Because it's not fair to say, as I did earlier, that my initial experiences of my brother were primarily as enigma or closed door. My earliest memory of him, in fact, is of the way, when I was very small and committed to thumb sucking, he'd catch sight of me doing so, and unsure of what to do with his excess of tenderness, he'd rush over to me and cup his hands around my fist, the one connected to the thumb in my mouth, so that we'd be nose to nose. I'd always shake him off with a faux irritation, but I knew how loving a gesture it was, and I cherished it for that reason.

And when I made those top-ten lists, and when he wasn't in his dark periods, we'd sit in his room and he'd tease me about how I could possibly have elevated the Dave Clark Five to a spot above the Kinks, or what I was thinking of, putting Herman's Hermits on the list at all. "Hey, it's your record," I would tease him back, and he'd shake his head ruefully in agreement, as if to wonder, the same way I wondered: Who knows why he did certain things sometimes. That first short story that dealt with my brother formed the anchor story for my first collection, and then reappeared in a volume of new and selected stories, and then inspired a third collection, which turned out to be about all sorts of brother issues, both wide-ranging and close to home. Has my brother read those stories? It's hard to say. I don't ask, and he doesn't volunteer the information. He's now living in my parents' condominium in Florida. I have, though, found copies of my books thumbed-through when I've visited him down there. As he's gotten older he seems to have shed those rage issues and found a certain peace with his situation—even if he hasn't gotten much more outgoing in social terms. We talk on the phone, not nearly as often as we should, but often enough to retain the intensities of our bond.

Delmore Schwartz has an understandably famous short story called "In Dreams Begin Responsibilities," which features a young narrator who finds himself in a movie theater watching a silent film of his parents' courtship. The narrator in the act of watching is awakened to himself and to his own unhappiness, as he puts it. He stands, at the moment his father proposes marriage to his mother, and shouts at the screen: "Don't do it! It's not too late to change your minds, both of you. Nothing good will come of it, only remorse, hatred, scandal, and two children whose characters are monstrous." But what's wonderful about Schwartz's story is how clear-eyed it is about its protagonist's shortcomings. It is, after all, called "In Dreams Begin Responsibilities." Those responsibilities we have to those in our lives that we love: If we're lucky, we rehearse them on paper. There's so much to overcome, both on the page and off. It's easy to think, "Where to begin?" But I take heart from an analogy of E.L. Doctorow's about the act of faith involved in writing fiction. He once remarked that writing a novel was like driving alone at night: You could only see as far as your headlights. But you could go the whole way like that.

This essay appears in Brothers: 26 Stories of Love and Rivalry (Jossey-Bass), published in May 2009.