How do you deal with emotionally charged items you can't live with—or without?

The garbage bag bulges with sweaters, dresses, tunics, shoes, and belts that have languished in my closets for years, waiting for a comeback that's just never gonna come. Shirts that no longer button. Bras built for my '90s-era bust. A rain hat that has lived a life of captivity inside a drawer, never having felt a single drop.

Two other Hefties sit with their mouths open, waiting to be fed. My possessions avert their gaze, as if afraid to attract attention. You there! You ugly, itchy, horizontally striped alpaca poncho bought at that street fair—to the Hefty! Random candlestick: Hefty! Mystery cell phone charger, stop trying to hide behind the Flip camera!

This lack of mercy isn't like me, and that's the point. No matter how redundant or useless my possessions, no matter the money they cost me each time I move, an overwhelming glut of stuff has always found sanctuary in my home. But now that my home is a Boston apartment barely big enough for one human and her little dog, I've had it. I shouldn't have to spend so much time jostling for space. My energies should go to friends and family and work, not to the continual repuzzling of junk: the never-worn suits, the nearly identical pairs of boots, the proliferation of sofa pillows, the—not even kidding—velvet and taffeta ball gown, price tags intact. Barnacles, all.

I knew I had to act when I caught myself saving that rectangle of cardboard that comes at the bottom of the Chinese-takeout delivery bag because I might need it someday. So last fall I started loading boxes and bags with orphaned earrings, burdensome purses, heavy ruby curtains I haven't used since that time I had the peeping Tom. Getting rid of such things is easy—they mean nothing to me. Even I can admit the logic of saying goodbye to all but one of three colanders, all but one of four coffeemakers. I know I don't really need a whole forest of brooms. Or 12 glass canisters of varying heights.

Steadily, the boxes and bags have filled. The surplus stuff has gone out into the world via Freecycle and eBay and the Salvation Army. There's just one problem. When I began, I figured the more I purged the lighter and less complicated my life would feel. Surprisingly, though, nothing feels that way except the cabinets and floors.

In the past 12 years, I've lived in Charlotte, Boston (twice), Atlanta (twice), Manhattan, Portland (the one in Oregon), Oxford (the one in Mississippi), Europe, and on Long Island. My first move, in 1999, the one that signaled the beginning of the end of my four-year marriage, was back to my birthplace, Oxford, in the wake of my father's death: I left my husband in Charlotte while I went to teach at Ole Miss for a year and be near my family.

But when the visiting professorship ended, instead of moving to the home my husband and I had just bought in Atlanta, where he had taken a new job, I ran off to Spain. After Spain came Atlanta again, just long enough for the divorce. Then New York, where I moved for graduate school. Then Atlanta yet again, for a magazine job. Then Portland, for another magazine job. And finally to Boston, where I teach at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard.

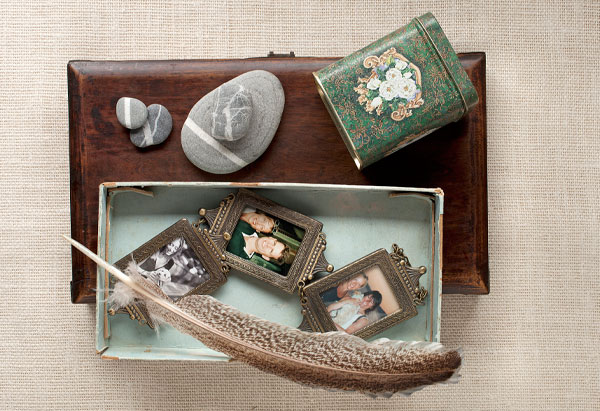

I can trace all these moves by the artifacts that travel with me wherever I go. The little Moroccan jar is where I stored my wedding ring when I lived in Spain. The photo of my ex and me smiling on a downtown sidewalk was taken in Charlotte before I left. The green and gold tin on the bookshelf contains the ashes of my cat Harry, whom I adopted as a kitten in 1990.

Poor Harry. When I left the marriage, he—like the furniture, the Christmas ornaments, my favorite rice cooker, all the odds and ends my husband and I had accumulated in our decade together—stayed behind. But when my ex remarried, and the new wife was allergic, Harry had to go. By this point, I was living in a 200-square-foot Manhattan studio apartment, with a terrier that craved kitties as snacks. Harry went to stay with my mother.

When I moved to Atlanta (the second time, in 2006), Harry came home. By then he was skinny, elderly, mewling, and living like an afterthought. The morning he could no longer stand, I took him to the veterinarian; alone and sobbing, I held him as they administered the final injection. Since then, each time I've passed his tin of ashes I've thought not of his formerly happy life (sunbeams, cuddles) but rather of his miserable final years of displacement and exile and—I know I'm anthropomorphizing here—confusion and despair.

Now, however, surrounded by all these outgoing Hefties, I look at that tin and think: "I bet I'd feel better if I took care of that." Why am I hanging on to something that makes me feel wretched? Moreover, how did I convince myself that Harry should spend eternity on a dusty bookshelf in the first place? He deserves an actual, ceremonious farewell, and I know just the place: at the last real home he ever knew, in the yard of our old house in Charlotte, where he roamed hosta patches and woodpiles and lounged on a sunlit porch and spent every night curled up on a bed or sofa or in the crook of a neck, purring and warm.

So in January, in the course of my holiday travels, that is where I take him: to Charlotte, to the bungalow we all loved, now the home of another nice family. With their permission, I stand beneath the Japanese maple my ex and I planted in memory of my father. "You were a good and beautiful boy, Harry, and I'm grateful that I knew you," I say. "I'm sorry if I let you down, but I loved you." Then I open the plastic bag and pour out his remains. The act feels freeing and important. For so long I believed I'd suffer horrible guilt if I ever scattered those ashes, but what I feel is closer to redemption. I've found Harry's fitting end.

And it occurs to me: What if I could find similarly soothing finales for other troubling possessions—other relics I haven't been able to part with even though they weigh me down? This is the purge I need to make my life lighter and less complicated! For the weightiest possessions, I'll simply go about finding their respective heavens.

It takes about 45 seconds to identify the most hurtful offenders. The soul shredders are everywhere. There's the painting I bought after reluctantly leaving New York, where my dream life was supposed to start, for Atlanta. I hoped the painting would cheer me up, but it had the opposite effect—it seemed to get uglier and more mocking by the day. There are the books my friends have published, which only remind me that I've yet to begin publishing my own. There's the Japanese postcard from my ex-mother-in-law, whom I loved and admired and who recently died. And there's that tiny photo in the Victorian frame.

Because it's so tiny—a mere one inch by two—I start with the photo: a shot of my old friend Carol and me. She and her husband and brother had come to visit me in Spain, and we were on a ferry to Morocco. In the background, sea and sunset. We are tanned and smiling, our hair blowing in the wind.

Carol was one of the first people I met when I moved to North Carolina, weeks out of college, to become a reporter. She was crazy-smart, funny, ambitious, well mannered, a vocabulary ninja. An investigative reporter, she could dethrone a nefarious public official by 6 P.M. and shop for cute earrings on her way home. She set the standard for friendship, journalism, and womanhood, and she set it high.

Today every one of my female friends is some version of Carol. The problem is, Carol has slipped away. Somewhere amid all my moves and our respective marriages and my divorce and her motherhood and our exhausting careers, our signal friendship faded. I've kept her photo up no matter where I've lived, but now that I'm defusing emotional land mines by putting them in their proper place, I need a more fitting resolution. I could wrap the photo in tissue and store it away, or remove it from the frame and slip it into an album, but then it hits me—the problem isn't the photo; it's what the photo represents. What do you do with a picture that reminds you of failure? Here's what: You turn it into a portrait of resurrected friendship. If Carol has meant so much to the quality and trajectory of my time on Earth, I should call her.

Now, however, surrounded by all these outgoing Hefties, I look at that tin and think: "I bet I'd feel better if I took care of that." Why am I hanging on to something that makes me feel wretched? Moreover, how did I convince myself that Harry should spend eternity on a dusty bookshelf in the first place? He deserves an actual, ceremonious farewell, and I know just the place: at the last real home he ever knew, in the yard of our old house in Charlotte, where he roamed hosta patches and woodpiles and lounged on a sunlit porch and spent every night curled up on a bed or sofa or in the crook of a neck, purring and warm.

So in January, in the course of my holiday travels, that is where I take him: to Charlotte, to the bungalow we all loved, now the home of another nice family. With their permission, I stand beneath the Japanese maple my ex and I planted in memory of my father. "You were a good and beautiful boy, Harry, and I'm grateful that I knew you," I say. "I'm sorry if I let you down, but I loved you." Then I open the plastic bag and pour out his remains. The act feels freeing and important. For so long I believed I'd suffer horrible guilt if I ever scattered those ashes, but what I feel is closer to redemption. I've found Harry's fitting end.

And it occurs to me: What if I could find similarly soothing finales for other troubling possessions—other relics I haven't been able to part with even though they weigh me down? This is the purge I need to make my life lighter and less complicated! For the weightiest possessions, I'll simply go about finding their respective heavens.

It takes about 45 seconds to identify the most hurtful offenders. The soul shredders are everywhere. There's the painting I bought after reluctantly leaving New York, where my dream life was supposed to start, for Atlanta. I hoped the painting would cheer me up, but it had the opposite effect—it seemed to get uglier and more mocking by the day. There are the books my friends have published, which only remind me that I've yet to begin publishing my own. There's the Japanese postcard from my ex-mother-in-law, whom I loved and admired and who recently died. And there's that tiny photo in the Victorian frame.

Because it's so tiny—a mere one inch by two—I start with the photo: a shot of my old friend Carol and me. She and her husband and brother had come to visit me in Spain, and we were on a ferry to Morocco. In the background, sea and sunset. We are tanned and smiling, our hair blowing in the wind.

Carol was one of the first people I met when I moved to North Carolina, weeks out of college, to become a reporter. She was crazy-smart, funny, ambitious, well mannered, a vocabulary ninja. An investigative reporter, she could dethrone a nefarious public official by 6 P.M. and shop for cute earrings on her way home. She set the standard for friendship, journalism, and womanhood, and she set it high.

Today every one of my female friends is some version of Carol. The problem is, Carol has slipped away. Somewhere amid all my moves and our respective marriages and my divorce and her motherhood and our exhausting careers, our signal friendship faded. I've kept her photo up no matter where I've lived, but now that I'm defusing emotional land mines by putting them in their proper place, I need a more fitting resolution. I could wrap the photo in tissue and store it away, or remove it from the frame and slip it into an album, but then it hits me—the problem isn't the photo; it's what the photo represents. What do you do with a picture that reminds you of failure? Here's what: You turn it into a portrait of resurrected friendship. If Carol has meant so much to the quality and trajectory of my time on Earth, I should call her.

Which is exactly what I do. I call her at work and leave a message; a few days later, she leaves one back. Hearing the familiar voice triggers no pain, no guilt—just an instant sense of familiarity, and of having missed her. It's only a couple of voice mails—we aren't insta-BFFs—but it is a step, and for the first time in years, that tiny photo doesn't feel like leaden baggage.

In the days that follow, object after object finds its rightful resolution. The ugly painting: to eBay, and someone who will appreciate it. The books authored by friends: side by side on their own special shelf, not as taunts but as inspiration. The Japanese postcard: properly framed, in proper tribute to a woman whose encouragement helped channel the course of my life.

But then I get to the rocks.

There are four of them: a mama rock the size of a flattened grade A jumbo egg, and triplets big enough to skip across the smooth surface of a lake. They are Italian, these rocks, dark gray with bold white stripes. They come from a secret beach in the Cinque Terre, from the last real vacation I ever took with my husband.

The beach lay at the end of a dark abandoned train tunnel. I walked that grim distance alone, out of stubbornness, because I didn't agree that ducking into the hotel to freshen up first was the best use of our time. I didn't want to waste daylight. I wanted to get where I was going. So despite a tunnel entrance marked DANGER, off I went, keeping my eyes on the distant pinpoint of light, hearing nothing but the sound of my own footfall and nervous breathing.

The beach was worth it. By the time my husband joined me, I had collected two dozen or more of those zebra rocks. I wanted them for our house, to remind me of this trip. I would not be able to take the lemon tree that stood outside our hotel room door, or the moon so full and bright on the water it woke us up at night. The rocks, though, I could tuck into my backpack and haul home on the plane.

"Peg, please," my husband said, using his nickname for me as we left the beach that day. "Lose the rocks." He saw no point in hauling home a load of stones. More urgently, we had 365 steps to climb to get back to the hilltop village where we were staying.

A third of the way up, I ditched the first few rocks. Soon I dropped a few more. By the top of the stairs I was down to four, and I have wrapped and packed them up and carried them with me ever since. In New York I kept them on the built-in bookshelf near the window overlooking a Dickensian roofscape of puffing stovepipes. In Portland they sat on my antique desk. In Boston, in this current apartment, so old and sloping I've shimmed every piece of furniture, they've lived in a carefully crafted pile on a bookshelf with Orwell and Melville and Auster.

I love the rocks because they remind me of Italy, and because they are beautiful and real, and because some force of nature made them that way. Yet every time I see them, I feel the ghost of happier times, and of my failed marriage. In fact, the marriage has haunted most of the objects weighing me down. Harry was our cat. And Carol never would have visited me in Spain had I not run away from home. And though I told myself I bought the ugly painting because I was sad about leaving New York, it's no coincidence that I bought it mere hours after seeing my ex, his new wife, and their new baby, standing on the street corner outside our formerly favorite café, in the neighborhood where they still lived in our ex-house, with our ex-furniture, and my ex-dog.

On the loneliest days I have imagined myself living there still. Us, together, a life with all its attendant rituals and comforts.

In the days that follow, object after object finds its rightful resolution. The ugly painting: to eBay, and someone who will appreciate it. The books authored by friends: side by side on their own special shelf, not as taunts but as inspiration. The Japanese postcard: properly framed, in proper tribute to a woman whose encouragement helped channel the course of my life.

But then I get to the rocks.

There are four of them: a mama rock the size of a flattened grade A jumbo egg, and triplets big enough to skip across the smooth surface of a lake. They are Italian, these rocks, dark gray with bold white stripes. They come from a secret beach in the Cinque Terre, from the last real vacation I ever took with my husband.

The beach lay at the end of a dark abandoned train tunnel. I walked that grim distance alone, out of stubbornness, because I didn't agree that ducking into the hotel to freshen up first was the best use of our time. I didn't want to waste daylight. I wanted to get where I was going. So despite a tunnel entrance marked DANGER, off I went, keeping my eyes on the distant pinpoint of light, hearing nothing but the sound of my own footfall and nervous breathing.

The beach was worth it. By the time my husband joined me, I had collected two dozen or more of those zebra rocks. I wanted them for our house, to remind me of this trip. I would not be able to take the lemon tree that stood outside our hotel room door, or the moon so full and bright on the water it woke us up at night. The rocks, though, I could tuck into my backpack and haul home on the plane.

"Peg, please," my husband said, using his nickname for me as we left the beach that day. "Lose the rocks." He saw no point in hauling home a load of stones. More urgently, we had 365 steps to climb to get back to the hilltop village where we were staying.

A third of the way up, I ditched the first few rocks. Soon I dropped a few more. By the top of the stairs I was down to four, and I have wrapped and packed them up and carried them with me ever since. In New York I kept them on the built-in bookshelf near the window overlooking a Dickensian roofscape of puffing stovepipes. In Portland they sat on my antique desk. In Boston, in this current apartment, so old and sloping I've shimmed every piece of furniture, they've lived in a carefully crafted pile on a bookshelf with Orwell and Melville and Auster.

I love the rocks because they remind me of Italy, and because they are beautiful and real, and because some force of nature made them that way. Yet every time I see them, I feel the ghost of happier times, and of my failed marriage. In fact, the marriage has haunted most of the objects weighing me down. Harry was our cat. And Carol never would have visited me in Spain had I not run away from home. And though I told myself I bought the ugly painting because I was sad about leaving New York, it's no coincidence that I bought it mere hours after seeing my ex, his new wife, and their new baby, standing on the street corner outside our formerly favorite café, in the neighborhood where they still lived in our ex-house, with our ex-furniture, and my ex-dog.

On the loneliest days I have imagined myself living there still. Us, together, a life with all its attendant rituals and comforts.

Eight years after that breakup, people continue to ask why the marriage ended. Among the possible answers: We were the right fit at the wrong moment. We were the wrong fit. We didn't try hard enough. Fate. All I know is that at the time, leaving felt like the only thing to do. I've lived with the yoke of that decision and its collateral damage: relatives who never had the chance to say goodbye; close friends who mourned our breakup as if one of us had died; Harry; an apparently intractable sense of loss.

Meanwhile, my ex moved on. A few years ago, he and his wife sold the last of my things at a yard sale (after kindly asking permission), and voilà, I was gone.

For the longest time I believed that getting rid of sentimental objects amounted to a sort of denial. I told myself it was braver to face the presence of old sorrows than to put them out of sight. Now I wonder if it's braver to let the wounds finally close. In giving up the rocks, I would be doing more than letting go of painful memories; I would be denying them the power to stand in the way of future happiness.

Last summer my friends Pam and Charlie let part of their backyard grow into a wild and gorgeous meadow. Massachusetts wildflowers sprang up alongside butterfly bushes and tall silky grasses. Pam and Charlie and their 8-year-old son, George, love being able to see the meadow from their flagstone terrace and from the broad windows of their beautiful house.

I no longer have the marriage, the home, the life I once lived—the life I believed I should live. But I have this life, in which I love my work, my family, my friends, my city—and in which, thanks to this purge, I'm starting to like my prospects for getting on with things. Maybe, finally, it really is time to dwell on the pleasures of now instead of clinging to what is gone.

And so right around the time the wild meadow begins to bloom, I will bundle up the Italian rocks, my companions for nearly 15 years, and take them on one last journey. I will toss them into the overgrown loveliness, beneath swirling thermals that carry red-tailed hawks, in the company of two good people raising one good boy. The rocks will return to nature, where they belong, and I will be that much lighter, readier to reach for whatever comes next.

Paige Williams has won a National Magazine Award for feature writing, and her work has been anthologized in The Best American Magazine Writing.

Ready to Start Getting Rid Of Your Stuff?

Meanwhile, my ex moved on. A few years ago, he and his wife sold the last of my things at a yard sale (after kindly asking permission), and voilà, I was gone.

For the longest time I believed that getting rid of sentimental objects amounted to a sort of denial. I told myself it was braver to face the presence of old sorrows than to put them out of sight. Now I wonder if it's braver to let the wounds finally close. In giving up the rocks, I would be doing more than letting go of painful memories; I would be denying them the power to stand in the way of future happiness.

Last summer my friends Pam and Charlie let part of their backyard grow into a wild and gorgeous meadow. Massachusetts wildflowers sprang up alongside butterfly bushes and tall silky grasses. Pam and Charlie and their 8-year-old son, George, love being able to see the meadow from their flagstone terrace and from the broad windows of their beautiful house.

I no longer have the marriage, the home, the life I once lived—the life I believed I should live. But I have this life, in which I love my work, my family, my friends, my city—and in which, thanks to this purge, I'm starting to like my prospects for getting on with things. Maybe, finally, it really is time to dwell on the pleasures of now instead of clinging to what is gone.

And so right around the time the wild meadow begins to bloom, I will bundle up the Italian rocks, my companions for nearly 15 years, and take them on one last journey. I will toss them into the overgrown loveliness, beneath swirling thermals that carry red-tailed hawks, in the company of two good people raising one good boy. The rocks will return to nature, where they belong, and I will be that much lighter, readier to reach for whatever comes next.

Paige Williams has won a National Magazine Award for feature writing, and her work has been anthologized in The Best American Magazine Writing.

Ready to Start Getting Rid Of Your Stuff?

Photo: Burcu Avsar