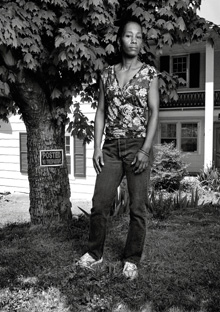

Photo: Mary Ellen Mark

In the fifth year of fighting for justice over her daughter's horrific murder and a life-threatening assault by her estranged husband—tragedies that could have been prevented if domestic violence laws had been enforced—Vernetta Cockerham's case ended with a financial settlement on June 30th, 2009.

When Vernetta Cockerham entered the Yadkin County Courthouse on June 29, 2009, for the start of a trial in her five-year case against the town of Jonesville, NC, and two of its police officers, she was not alone. Behind her, filling up the rows in the courtroom, was a gathering of supporters from advocacy groups across the state who had come to show strength and solidarity with her mission. Vernetta, poised and quiet up front, was touched by the display. "We had a small stand-in for justice," she says. "It was beautiful." In November 2002, the unthinkable happened to set these events into motion: Her estranged husband, Richard Ellerbee, broke into her house and brutally bound, beat, and suffocated her 17-year-old daughter, Candice, and then injured Vernetta within inches of her life (a long scar runs down her neck as evidence). She had gotten a protective order (also known as a restraining order) against him, and in the month leading up to the attack, she had done everything in her power to make sure the order was enforced, reporting his violations to the local police. By law, he should have been thrown in jail for those actions, and the evening before the crime, she says, the police assured her he would be behind bars.

It took a long time for Vernetta's wounds to heal, both physically and mentally, and almost exactly two years after that fateful day, Vernetta filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Jonesville and two police officers. Now, five years later, on Tuesday, June 30, 2009, a settlement was reached just a day after the case was about to go to trial. A jury pool had been called on Monday and at the close of the day, lawyers from both sides met to discuss jury selection but wound up coming to a settlement instead. When court reconvened the next morning, the judge announced the case had been settled and Vernetta was awarded a sum of $430,000.

"I was never there to beat up the town financially or get millions and millions of dollars. I began this case—I think we put in for $10,000 at first—because I wanted to try to start a shelter for battered women," she says. "It took a long time, but this was well worth the wait for the people that it's going to help. The strengthening of domestic violence laws is happening right now, and I love being involved. I'm hoping to be able to implement services and changes in Yadkin county; that's what the settlement means to me."

Much of Vernetta's involvement and advocacy work has been done through the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence. She is an active volunteer, and she has spoken numerous times about her ordeal and will continue to be involved in as many ways as she can. The coalition's executive director, Rita Anita Linger, who was in the courtroom both Monday and Tuesday, welcomes her efforts.

Of course, you can't put a dollar figure on what Vernetta has been through—the death of her daughter, the extent of her injuries, and how her family was altered. "More important than dollars and cents is that on some level justice has been served," says Linger. "With the decision, the police department is not acknowledging they did anything wrong on paper at least, but I think the facts and outcome speak for themselves. Anyone who looks at the specific details of this case will see that the end result was a long time in coming, and what really impressed me about Vernetta is that she immediately went into advocacy mode, being a support to other victims and looking for the systemic gaps and how we can fix them."

One such systemic gap directly resulted from her legal battle. When her case was heard by the North Carolina Court of Appeals in 2006, even though they gave her the right to proceed with the case, they interpreted a section of the law to be a discretionary, not mandatory, provision. Where it said that if a person violated a protective order he or she would be arrested, the court felt the wording was ambiguous and didn't mean a police officer must make an arrest. This year, with renewed light on the case, Representative Earline Parmon in the North Carolina General Assembly filed a bill on April 13th to clarify it; House Bill 1464 passed on May 14th and it awaits a vote in the state senate.

"The legislators, my fellow colleagues, were really taken back and surprised that the court made that decision based on the language, so they were very eager to ensure the meaning would never again be mistaken," says Parmon. "I wanted to make sure that we got this done because it was a very tragic case, and it never should have happened. The abuser should have been arrested, and the police had plenty of opportunities to do it and for some reason didn't."

The bill was supposed to be voted on earlier this month, but it has been pushed back on the senate voting schedule. Parmon, Linger, and Cockerham are all optimistic the bill will pass, thereafter becoming a law. Vernetta hopes it can be named in Candice's honor; Parmon feels this would be possible and appropriate.

One of Cockerham's lawyers, Harvey Kennedy, sees Cockerham's case and the new bill as part of a general trend to strengthen domestic violence laws. "I think a lot more cases in the future will be successful and the law is continuing to develop in this particular area."

As for Vernetta, she plans on finding new ways that she can help out both big (building a family court near Jonesville) and small (counseling other victims). Linger doesn't see an end to the possibilities: "I've been doing this for years in a state coalition, and I'm beyond impressed with her. She is a perfect example of an advocate for domestic violence. She has done everything right, and the most important thing she's done is that she never gave up."

Read Vernetta's full story