Devastating Drug Addiction

Addiction is a painful secret many families are too ashamed to discuss. In 2005, one father came forward in a very public way to share what it was like to love a child whose drug and alcohol abuse threatened to tear their family apart.

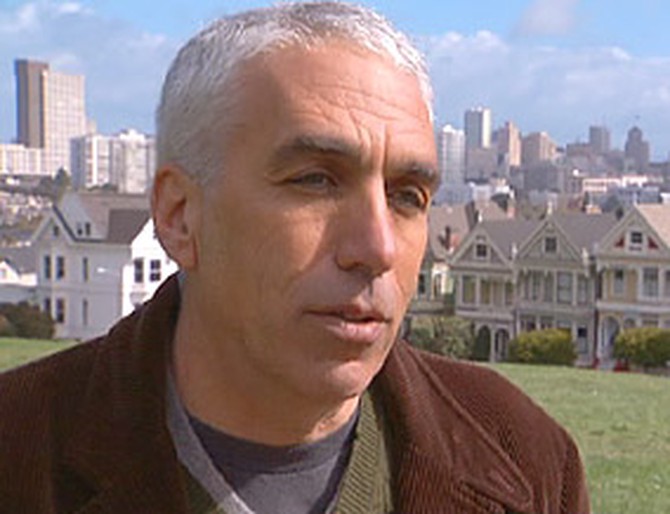

Award-winning journalist David Sheff wrote about his struggle to help his son Nic overcome a crystal meth addiction in The New York Times Magazine. After the article was published, David says he realized he was not alone. His story generated an overwhelming response from other parents of addicts.

"When this hit our family, we were like so many families in this country," David says. "I was not naive about drugs. I used drugs when I was a kid. ... But I still thought, like most of us, 'This could never happen to our family.' When it did, we were so blindsided. We were so devastated that I realized that this is something we have to talk about."

David delves deeper into Nic's drug abuse and its impact on their family in his book Beautiful Boy. "I realized the power of telling a story like this because it opens the door to other people," he says. "It gives people permission [to discuss it]."

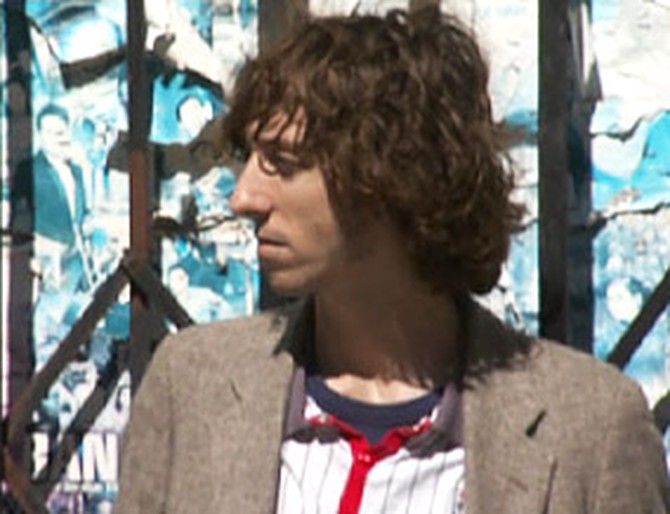

Using journals he kept throughout his life, Nic has also written a version of the story. In his memoir Tweak: Growing Up on Methamphetamines, he recounts his experiences as a teenage drug addict to the best of his recollection.

Award-winning journalist David Sheff wrote about his struggle to help his son Nic overcome a crystal meth addiction in The New York Times Magazine. After the article was published, David says he realized he was not alone. His story generated an overwhelming response from other parents of addicts.

"When this hit our family, we were like so many families in this country," David says. "I was not naive about drugs. I used drugs when I was a kid. ... But I still thought, like most of us, 'This could never happen to our family.' When it did, we were so blindsided. We were so devastated that I realized that this is something we have to talk about."

David delves deeper into Nic's drug abuse and its impact on their family in his book Beautiful Boy. "I realized the power of telling a story like this because it opens the door to other people," he says. "It gives people permission [to discuss it]."

Using journals he kept throughout his life, Nic has also written a version of the story. In his memoir Tweak: Growing Up on Methamphetamines, he recounts his experiences as a teenage drug addict to the best of his recollection.

As a little boy, Nic seemed to have it all. David says his son had a winning personality and a golden, shining light about him. "He had this sort of joyfulness, this love of life," David says.

When Nic was 4 years old, his parents divorced. He grew up splitting his time between his father's home near San Francisco and his mother's home in Los Angeles. For years, David says he thought Nic was handling the difficult situation well. "He was almost always on the honor roll," David says. "He was the captain of the water polo team."

Despite appearances, Nic says he felt so much pain inside he went searching for something to numb his emotions. When he was just 11 years old, Nic says he got drunk for the first time. "The world was really abrasive and overwhelming, and I felt really hopeless," he says. "When I started drinking [alcohol], I couldn't stop."

One year later, David found marijuana in his son's backpack. Nic eased his father's fears by saying he'd made a mistake, but the truth was, he was secretly smoking pot every day by the time he was in middle school.

When Nic was 4 years old, his parents divorced. He grew up splitting his time between his father's home near San Francisco and his mother's home in Los Angeles. For years, David says he thought Nic was handling the difficult situation well. "He was almost always on the honor roll," David says. "He was the captain of the water polo team."

Despite appearances, Nic says he felt so much pain inside he went searching for something to numb his emotions. When he was just 11 years old, Nic says he got drunk for the first time. "The world was really abrasive and overwhelming, and I felt really hopeless," he says. "When I started drinking [alcohol], I couldn't stop."

One year later, David found marijuana in his son's backpack. Nic eased his father's fears by saying he'd made a mistake, but the truth was, he was secretly smoking pot every day by the time he was in middle school.

Over the years, David's dreams for his son began to slip away. Drugs like acid, mushrooms, ecstasy and cocaine became the center of his son's world. Then, when Nic turned 18, he says he tried crystal methamphetamine.

"The first time I did a line of crystal, it was like my whole world changed," Nic says. "I just felt confident and strong and like I could do anything. I felt like a rock star. It was like everything I'd been missing my whole life, and I wanted to hold on to that feeling because it was exactly what I needed."

Nic's euphoric feeling didn't last long. Hours after his first hit, he came crashing down from the high. "I remember lying in my bed, and I was sweating the drug out of my body, and I was shaking," he says. "It was just this intense, horrible, wrenching pain like someone had come in with a vacuum cleaner and just sucked out every good feeling that I'd ever had in my whole life."

After that day, Nic says he used crystal meth constantly because he was afraid of crashing again. His addiction began to consume his life and take a toll on every member of his family.

"Methamphetamine stole his soul," David says. "Our lives descended, Nic's life descended, into what can only be described as hell."

"The first time I did a line of crystal, it was like my whole world changed," Nic says. "I just felt confident and strong and like I could do anything. I felt like a rock star. It was like everything I'd been missing my whole life, and I wanted to hold on to that feeling because it was exactly what I needed."

Nic's euphoric feeling didn't last long. Hours after his first hit, he came crashing down from the high. "I remember lying in my bed, and I was sweating the drug out of my body, and I was shaking," he says. "It was just this intense, horrible, wrenching pain like someone had come in with a vacuum cleaner and just sucked out every good feeling that I'd ever had in my whole life."

After that day, Nic says he used crystal meth constantly because he was afraid of crashing again. His addiction began to consume his life and take a toll on every member of his family.

"Methamphetamine stole his soul," David says. "Our lives descended, Nic's life descended, into what can only be described as hell."

David says he knew his son was in trouble, but he was in denial about the extent of his addiction. "I kind of think we parents are wired for denial because to see the trouble that our child is in is so painful. It's so terrifying," he says. "I would hear the good things; I'd see the good things. I'd block out the terrifying course that we were on until it was impossible to deny anymore."

When Nic began skipping classes in high school, David says he spoke to teachers and a counselor about his rebellious behavior. "[They said], 'Nic's fine. He's a smart kid. He's doing fine. He's doing well in school,'" David says. "It wasn't that I completely dismissed it. I was worried. [But] I didn't take it seriously."

The counselor also told David college would straighten Nic out. "Did I believe it?" he says. "I wanted to believe it." Nic enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, but he didn't make it through his freshman year.

In an attempt to protect his son and himself, David says he hid Nic's addiction from friends and family at first. "I didn't want them to think badly of my son," he says. "I was ashamed. My son is a drug addict. What does this mean about me?"

When Nic began skipping classes in high school, David says he spoke to teachers and a counselor about his rebellious behavior. "[They said], 'Nic's fine. He's a smart kid. He's doing fine. He's doing well in school,'" David says. "It wasn't that I completely dismissed it. I was worried. [But] I didn't take it seriously."

The counselor also told David college would straighten Nic out. "Did I believe it?" he says. "I wanted to believe it." Nic enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, but he didn't make it through his freshman year.

In an attempt to protect his son and himself, David says he hid Nic's addiction from friends and family at first. "I didn't want them to think badly of my son," he says. "I was ashamed. My son is a drug addict. What does this mean about me?"

In Beautiful Boy, David writes about a time he shared a joint with his son, a decision he says he regrets to this day.

"Nic was already on this course, and I was desperate to connect with him," David says. "What does that say? The hypocrisy. ... It was not something I'm proud of."

David says he's heard stories of other parents trying the same tactic, but it's not something he recommends. "I took [the joint] without really thinking it through," he says. "But I did have the sense he was trying to open up to me. He was trying to talk."

When Nic was growing up, David says he made the decision to discuss his own experiences with drugs with his son. "When I was a child, my parents didn't know anything about drugs. They didn't even drink," he says. "When they said, 'Just say no,' ... I kind of rolled my eyes and thought they didn't know what they were talking about. I thought I'd have some credibility because I did know people whose lives were destroyed by drugs."

While some experts think parents should be honest with their children about past drug use, others argue that it sends a mixed message. Now, David says he's not sure if he should have opened up.

"They bring these athletes to schools or other people who have done well, and they say, 'Don't use drugs. I almost died.' Well, what do the kids see? They see this person who not only survived, but they're thriving," he says. "It is a mixed message. That's a problem. I think we have to better figure out how to talk to kids about this."

"Nic was already on this course, and I was desperate to connect with him," David says. "What does that say? The hypocrisy. ... It was not something I'm proud of."

David says he's heard stories of other parents trying the same tactic, but it's not something he recommends. "I took [the joint] without really thinking it through," he says. "But I did have the sense he was trying to open up to me. He was trying to talk."

When Nic was growing up, David says he made the decision to discuss his own experiences with drugs with his son. "When I was a child, my parents didn't know anything about drugs. They didn't even drink," he says. "When they said, 'Just say no,' ... I kind of rolled my eyes and thought they didn't know what they were talking about. I thought I'd have some credibility because I did know people whose lives were destroyed by drugs."

While some experts think parents should be honest with their children about past drug use, others argue that it sends a mixed message. Now, David says he's not sure if he should have opened up.

"They bring these athletes to schools or other people who have done well, and they say, 'Don't use drugs. I almost died.' Well, what do the kids see? They see this person who not only survived, but they're thriving," he says. "It is a mixed message. That's a problem. I think we have to better figure out how to talk to kids about this."

David tried many times to connect with his teenage son, but after years of abusing drugs, Nic ran away from home.

For the next five years, David says his son was on a suicide mission fueled by crystal meth. While living on the street, Nic says he dealt drugs, worked in the sex industry and stole money from his family to support his habit. At one point, Nic says he was so desperate, he came home to search for cash. He found a few dollars in his little brother's piggy bank and stole every penny. "Doing crystal made me into like an animal," he says. "I would have practically done anything to anybody in order to keep getting it."

Nic's addiction ravaged his family and his body. "I was really skinny," he says. "Crystal meth does this thing where you get kind of like scales on your skin."

Even after an overdose sent Nic to the emergency room, he refused to call his father. "I was afraid to call my dad. I was ashamed too," he says. "There was just this idea that I was just going to shoot drugs until I killed myself."

David says he used to scour the streets and search alleyways looking for his son. One day, David convinced Nic to meet him at a cafe to talk. When he didn't show up, David says he found him on the street, strung out on meth and looking very frail. "My heart just sunk," David says. "There was my son, my beautiful boy, and he looked like he was walking dead."

For the next five years, David says his son was on a suicide mission fueled by crystal meth. While living on the street, Nic says he dealt drugs, worked in the sex industry and stole money from his family to support his habit. At one point, Nic says he was so desperate, he came home to search for cash. He found a few dollars in his little brother's piggy bank and stole every penny. "Doing crystal made me into like an animal," he says. "I would have practically done anything to anybody in order to keep getting it."

Nic's addiction ravaged his family and his body. "I was really skinny," he says. "Crystal meth does this thing where you get kind of like scales on your skin."

Even after an overdose sent Nic to the emergency room, he refused to call his father. "I was afraid to call my dad. I was ashamed too," he says. "There was just this idea that I was just going to shoot drugs until I killed myself."

David says he used to scour the streets and search alleyways looking for his son. One day, David convinced Nic to meet him at a cafe to talk. When he didn't show up, David says he found him on the street, strung out on meth and looking very frail. "My heart just sunk," David says. "There was my son, my beautiful boy, and he looked like he was walking dead."

One of the lowest lows Nic says he had was when he decided to steal a computer from his mother, Vicki. "I was sitting here having coffee, and then I heard this strange mumbling noise in the garage," Vicki says. "The place was trashed. I was walking over clothes, books, everything. I looked up—he was in the rafters, just sitting there with all these clothes on him, and mumbling and not making a lot of sense."

Nic explains that he thinks he was experiencing amphetamine psychosis and was blacked out for most of the episode. "I'd seen [crystal meth] make other people go crazy, and it never really made me go crazy in that way, but I think that was the first time it did," he says. Nic says that during his psychosis he thought people were outside of the garage trying to spy on him. "I remember climbing up into the rafters and trying to peel off the shingles on the roof to try to climb out through the roof, which didn't work."

Nic explains that he thinks he was experiencing amphetamine psychosis and was blacked out for most of the episode. "I'd seen [crystal meth] make other people go crazy, and it never really made me go crazy in that way, but I think that was the first time it did," he says. Nic says that during his psychosis he thought people were outside of the garage trying to spy on him. "I remember climbing up into the rafters and trying to peel off the shingles on the roof to try to climb out through the roof, which didn't work."

Over the years, David says he begged his son to enter a rehabilitation program, but Nic refused.

There was even a time where David says he called hospitals and the morgue every few days to see if Nic had overdosed again or died. "I just had to wait, and I waited," David says. Eventually, Nic agreed to get help.

During one stint in rehab, Nic wrote in his journal, "How the hell did I get here? It doesn't seem that long ago that I was on the water polo team. I was an editor of the school newspaper. ... The kids in my class are in college. This isn't so much sad as it is baffling."

Nic says he never intended to be a drug addict, but once he was, he says he didn't want to stop. Rehab helped Nic recognize that he had a disease, but he says he wasn't convinced at first that he couldn't control his consumption of drugs and alcohol. David says he also struggled with the idea that his firstborn was an addict. "I was very naïve," he says. "I didn't understand addiction."

Over the years, Nic says he has relapsed multiple times and completed five rehabilitation programs. David says it's important for people to remember that relapses are part of the recovery process. "I thought, 'I'll pick him up in 30 days, and thank God, this will be over.' Well, that's not the way addiction works," David says. "Sometimes it takes awhile for them to get it. It's important to understand that because otherwise you feel so defeated. You realize that there's still hope."

When this show first aired in April 2008, Nic said he'd been clean for more than two years. Since then, he's relapsed twice. Today, he says he's clean.

There was even a time where David says he called hospitals and the morgue every few days to see if Nic had overdosed again or died. "I just had to wait, and I waited," David says. Eventually, Nic agreed to get help.

During one stint in rehab, Nic wrote in his journal, "How the hell did I get here? It doesn't seem that long ago that I was on the water polo team. I was an editor of the school newspaper. ... The kids in my class are in college. This isn't so much sad as it is baffling."

Nic says he never intended to be a drug addict, but once he was, he says he didn't want to stop. Rehab helped Nic recognize that he had a disease, but he says he wasn't convinced at first that he couldn't control his consumption of drugs and alcohol. David says he also struggled with the idea that his firstborn was an addict. "I was very naïve," he says. "I didn't understand addiction."

Over the years, Nic says he has relapsed multiple times and completed five rehabilitation programs. David says it's important for people to remember that relapses are part of the recovery process. "I thought, 'I'll pick him up in 30 days, and thank God, this will be over.' Well, that's not the way addiction works," David says. "Sometimes it takes awhile for them to get it. It's important to understand that because otherwise you feel so defeated. You realize that there's still hope."

When this show first aired in April 2008, Nic said he'd been clean for more than two years. Since then, he's relapsed twice. Today, he says he's clean.

Looking back, David says he realizes he was addicted to his son's addiction. "When he was on the streets, I was consumed with Nic," he says. "I was obsessed with him to the point that I could barely function."

Over time, David says his obsession put a strain on his relationships. "It was at the expense of my wife and my beloved little children, [but] how could a parent whose son is in mortal peril like this think about anything else?" he says.

David wasn't the only one worried about Nic. Karen, his second wife, their young children, Jasper and Daisy, and Nic's mother, Vicki, also suffered. "Karen was in tears," David says. "For Jasper and Daisy, they were very young, and they revered Nic. He was their big brother, their friend, their playmate. ... They didn't understand what he was doing to himself, and they didn't understand how a family had changed."

Over time, David says his obsession put a strain on his relationships. "It was at the expense of my wife and my beloved little children, [but] how could a parent whose son is in mortal peril like this think about anything else?" he says.

David wasn't the only one worried about Nic. Karen, his second wife, their young children, Jasper and Daisy, and Nic's mother, Vicki, also suffered. "Karen was in tears," David says. "For Jasper and Daisy, they were very young, and they revered Nic. He was their big brother, their friend, their playmate. ... They didn't understand what he was doing to himself, and they didn't understand how a family had changed."

The first time Nic read his father's book, he says the painful consequences of his actions began to sink in. "I cried a lot," he says. "I didn't really realize that when I was using and when I was trying to kill myself through using that I was really affecting everyone around me. ... When I read his book and just saw how much his life had been ripped apart by my using and how his marriage had been tested and how my little brother and sister were affected, it was devastating."

Nic admits that although he wasn't thinking clearly during his addiction, he wasn't completely blind to the burden he put on his family. "There was a little piece of me deep down that knew what I was doing was really tearing my family apart, but I didn't want to see that," he says. "I think that's part of the reason that I kept using drugs—to blot out that pain."

Nic says he realizes he started abusing drugs to avoid seeing his true self. "I felt like if I looked inside of myself, I would see that I was just this ugly, disgusting, worthless person. I was so scared of that, I started drinking and using so that I could escape," he says. "It's so stupid. I don't know what I was running from that whole time."

Nic admits that although he wasn't thinking clearly during his addiction, he wasn't completely blind to the burden he put on his family. "There was a little piece of me deep down that knew what I was doing was really tearing my family apart, but I didn't want to see that," he says. "I think that's part of the reason that I kept using drugs—to blot out that pain."

Nic says he realizes he started abusing drugs to avoid seeing his true self. "I felt like if I looked inside of myself, I would see that I was just this ugly, disgusting, worthless person. I was so scared of that, I started drinking and using so that I could escape," he says. "It's so stupid. I don't know what I was running from that whole time."

Since David began writing about his journey with Nic, he's connected with many other parents struggling with addict children. Like Nic, Karen and Gordon say their son, Noah, excelled in childhood. "He was very good in school," Karen says. "He always got all As. He was an excellent athlete."

On the inside, Gordon says Noah was suffering. "When he was 13, he was abused by a coach," Gordon says. "As a result of this heinous act, my son initiated the use of alcohol and drugs, which led to a spiraling of his suffering. Noah turned to marijuana and alcohol on a regular basis. Later in his life, he moved to things like cocaine and heroin."

Over a three-year period, Noah's parents say he was hospitalized 19 times and had 84 visits to the emergency room. "He tried recovery so many times," Karen says. "He was just a shell of himself."

To help wean Noah off cocaine, his parents say doctors prescribed methadone. Three days later, Karen and Gordon received a phone call they will never forget. "He was passed out," Gordon says. "A white substance had come out of his nose or mouth."

On the inside, Gordon says Noah was suffering. "When he was 13, he was abused by a coach," Gordon says. "As a result of this heinous act, my son initiated the use of alcohol and drugs, which led to a spiraling of his suffering. Noah turned to marijuana and alcohol on a regular basis. Later in his life, he moved to things like cocaine and heroin."

Over a three-year period, Noah's parents say he was hospitalized 19 times and had 84 visits to the emergency room. "He tried recovery so many times," Karen says. "He was just a shell of himself."

To help wean Noah off cocaine, his parents say doctors prescribed methadone. Three days later, Karen and Gordon received a phone call they will never forget. "He was passed out," Gordon says. "A white substance had come out of his nose or mouth."

Karen and Gordon went to the hospital, where they were asked to wait for doctors in a small, private room. "I knew what had happened because we had to go in that kind of a room and wait," she says. On July 28, 2006, Karen and Gordon were told their son was dead. When they were taken to see his body, Karen says she was surprised by what she saw. "He looked at such peace," she says. "He looked in the greatest peace that he had looked in over 10 years since this whole mess started."

Although there are differences, Karen says she can see herself in David and Nic's story. "To me, the disease of addiction is a family disease that is so insidious and so cunning and so baffling."

Although there are differences, Karen says she can see herself in David and Nic's story. "To me, the disease of addiction is a family disease that is so insidious and so cunning and so baffling."

Shortly after writing the article "My Addicted Son" for The New York Times Magazine, David received an e-mail from Kathleen, whose meth-addicted daughter, Maria, was begging to be bailed out of jail. David says he responded to Kathleen's e-mail with a personal story about his experience at Al-Anon, an organization for friends and family members of addicts. "I walked into an Al-Anon meeting one time, and I saw actually two parents, and they were weeping, and they said, 'My child is in jail, thank God.'" David says he was puzzled by their positive reaction until they explained that knowing their child was in jail meant he or she was no longer living on the streets.

David suggested that Kathleen get support so she would know she's not alone. "It helped tremendously," Kathleen says.

David suggested that Kathleen get support so she would know she's not alone. "It helped tremendously," Kathleen says.

Instead of bailing her daughter out of jail, Kathleen decided to show her love and support in a different way. "I wasn't going to go and see her every Sunday to hear her empty promises," Kathleen says. "I decided that I would send her a postcard every day. I wanted her to know that the postcards meant that I thought of her."

For the next three months, Kathleen poured her soul into 72 beautiful postcards written just for her daughter. "I wanted her to know that I was with her, and I was sharing her pain," she says. "I was sharing her fear, and I wanted her to know that we love her no matter what she does or where she is."

One postcard included a quote that Christopher Robin said to Winnie the Pooh, one of Maria's favorite childhood characters. "Promise me you'll always remember—you're braver than you believe, and stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think."

For the next three months, Kathleen poured her soul into 72 beautiful postcards written just for her daughter. "I wanted her to know that I was with her, and I was sharing her pain," she says. "I was sharing her fear, and I wanted her to know that we love her no matter what she does or where she is."

One postcard included a quote that Christopher Robin said to Winnie the Pooh, one of Maria's favorite childhood characters. "Promise me you'll always remember—you're braver than you believe, and stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think."

Maria says she has been clean since August 15, 2006, and it was prison that turned her around. "I never thought I would ever end up there," she says. "You know you're doing wrong, but something about that drug kind of just shields you away ... You just don't care. You're always chasing that next high, and basically you're going to do whatever it takes to get [it]—no matter who it hurts, how many times you hurt them, the repercussions after."

The thought of relapsing is still an everyday struggle for Maria. "You have that choice to either pick up or not. But for me, being the addict that I am, I know that one pickup or that one decision is going to land me right back to where I was—that endless spiral to destruction."

The thought of relapsing is still an everyday struggle for Maria. "You have that choice to either pick up or not. But for me, being the addict that I am, I know that one pickup or that one decision is going to land me right back to where I was—that endless spiral to destruction."

David says he used to think that being a father to Nic would be enough to save his son. "Thomas Lynch wrote, 'If we can't protect our children, what good are fathers?' And that's the way I felt." Ultimately, David found that it was not his decision. In Beautiful Boy, David writes, "Your children live or die without you. No matter what we do, no matter how we agonize or obsess, we cannot choose for our children whether they live or die. It's a devastating realization, but liberating."

Nic chose to live and says he's found purpose in life. "I feel that's my mission every day to be honest and open and vulnerable and raw," he says. In Tweak, Nic writes on the last page, "My secrets will kill me if I don't get honest about my life. I can't have recovery, so my challenge is to be authentic."

Can you stop children from using drugs? Watch as Nic offers advice to parents.

Nic chose to live and says he's found purpose in life. "I feel that's my mission every day to be honest and open and vulnerable and raw," he says. In Tweak, Nic writes on the last page, "My secrets will kill me if I don't get honest about my life. I can't have recovery, so my challenge is to be authentic."

Can you stop children from using drugs? Watch as Nic offers advice to parents.

Published 06/05/2009