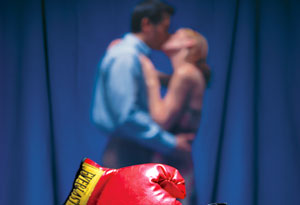

Photo: Brian Velenchenko

You landed a few good jabs and scored the final knockout point. But did you really win your last argument, or did you just KO your relationship? Therapist Jeffrey B. Rubin, PhD, steps in.

I heard them yelling in the waiting room. By the time I emerged from my office to greet them several minutes later, the well-dressed couple in their early 40s were silently fuming. I introduced myself and ushered them inside. The wife, Cathy, sat on the sofa; the husband, Robert, chose a nearby chair. They glared at each other. Without even waiting for me to ask why they'd come to see a therapist, Cathy exploded at Robert. "You're always working. You don't spend enough time at home. I feel like a work widow."

First Robert seethed, then he lit into Cathy. "Nothing is ever good enough for you," he said angrily. "I'm always working because you're always spending so much money."

She came right back at him. "At least I'm at home with the family, not married to my job. I might as well be single. In fact, I am."

"Yeah, but I'm not a critical bitch who's bankrupting the family."

It was time for me to intervene. "Throw me your wallets," I said. They looked at each other, then at me. "Hand them over."

They complied, intrigued enough to call a cease-fire. I took the wallets and put them on the ottoman at my feet. "Do you enjoy throwing your money away?" I asked.

They stared at me blankly.

"No," they both said.

"If you follow one principle—which I'll try my best to help you with—you'll save yourselves a lot of time, money, and tears," I said. "It's this: Be more interested in understanding your spouse than in winning. Otherwise, this process will take longer than it needs to, and you'll waste a lot of money trying to win. And you'll both lose. Guaranteed."

Now I had their attention.

In more than 24 years of practice, I've discovered that the biggest source of conflict for couples isn't money, sex, fidelity, child rearing, or in-laws. It's the urge to win. Wanting to win, to be right, is natural; it makes us feel strong and safe and gratified. It's also disastrous for a relationship. When the goal is winning instead of understanding, partners are more likely to ignore, or trample, each other's feelings. That launches a spiral of escalating resentment and hostility leading to alienation—a troubling distance from each other that can become unbridgeable when communication breaks down completely.

If the results are so dire, why do so many people continue to focus on defeating their partners rather than on hearing and understanding them? For a variety of reasons. Some go for the win as a sort of preemptive strike—if they hit first, they believe on some barely conscious level that they can avoid being shamed, humiliated, or bullied. Others think that crushing their mate is the only course of action open to them—they're afraid that unless they're overpowering, they'll be overpowered; that unless they're hollering, or building an airtight case against the other person, they won't be heard at all. They think the only available choices are conqueror or doormat. Winning makes some people feel—for a moment—safe and triumphant, and these short-term gains fool them into thinking that they've chosen the right tactic. But, paradoxically, going for the win is the course of action least likely to get them what they really want.

You know you're getting stuck in this dead-end strategy when being right is more important to you than improving the relationship, or when you constantly question or deny your partner's feelings and perceptions: One of you begins a sentence with "I feel..." and the other says, "No, you don't" or "You shouldn't." You know you're stuck when your conversations sound more like hostile debates than open-spirited collaborations, when you regularly interrupt each other, or when, instead of listening, you mentally rehearse what you're going to say while your mate is speaking.

How to break the cycle

The way to break the cycle is by cultivating understanding through compassionate listening. By that I mean hearing what your partner is really saying and feeling, instead of bracing for what you're sure he's going to say—and you're going to dismiss. In compassionate listening, also called empathetic or reflective listening, you might not always agree with your partner, or enjoy hearing what he has to say, but you still strive to understand his logic and the deepest emotions beneath it. When each of you is committed to understanding the other's point of view, you begin to create an atmosphere of trust and safety that encourages working together to solve your problems and begins to extinguish the urge to fight.

In that first session with Robert and Cathy, I explained the components of compassionate listening. I asked each of them to speak about one troubling issue, detailing their own feelings rather than attacking the other person. The listener's task would be to resist the urge to interrupt, criticize, or argue, and instead to repeat what the speaker said, including the deeper feelings beneath the content, until the speaker is satisfied that he or she has been heard. "When something your partner says triggers irritation or anger," I told them, "instead of getting emotionally hijacked by your reactions, you can do a quick exercise: Shift attention to the quality of your breathing, which may be shallow, constricted, or labored, especially if you're angry, and try elongating the exhalation." This relaxes the body and the mind just enough to short-circuit intense emotions and allow you to tune back in to what your partner is saying. Another trick for compassionate listeners who find themselves beginning to boil is to remind themselves, "I don't have to agree. I don't even have to solve this problem. All I have to do is understand what the other person is saying and feeling." Looking into your partner's eyes can also quickly reconnect you.

Robert spoke first. He told Cathy that he was concerned about money.

"So am I," Cathy said, defensively.

"When Robert is finished, you can speak, Cathy."

"I'm scared," Robert said. "Everything feels like a house of cards."

Cathy's expression began to soften. Eager to heal the breach, obviously grasping the principle of compassionate listening and perhaps touched by the risk he just took, Cathy empathized with Robert. "You're really feeling pressure, aren't you?" she said.

"That's what I've been trying to tell you for years."

"I always felt you were attacking me," Cathy said.

"It's about me, not you," he said. "I feel fearful about money."

"I want to know what that pressure feels like for you," she said.

"I'm worried about our future," Robert said. "I feel we need to live on a smaller scale and have more of a safety net in case something happens to me. My father died at my age, you know."

Cathy was leaning toward Robert, listening intently. "I'd like to have more time with you and the kids," Robert said, "but in order to do that, I'd need to work less—and one way to make that possible is to lower our expenses."

"You're worried about our financial future. You feel great pressure, and you'd like us to spend less so you can have more time with the family," Cathy said. "Do you feel that I'm hearing you?"

"For once," Robert said.

I felt the sting of his accusation. Cathy looked as if she did, too.

"Understanding, not winning," I reminded him.

Robert took a deep breath. "Yes, I feel you heard me, Cathy. Thank you." Their small, tentative smiles gave me hope.

In the past, when Cathy and Robert argued about money, he felt she was mocking his fears. But she didn't hear fears—only attacks on her spending habits. So she'd strike back; he'd feel humiliated and he'd counterattack. Cathy, who came from a family in which her needs were often belittled or ignored, saw Robert's hostility as evidence that he didn't care about her feelings; she'd further retaliate by withdrawing or treating him with contempt, which made him feel even more humiliated, so that he said even meaner things to her.

But compassionate listening broke that cycle. Once Robert believed Cathy heard his concerns and would even help him to express his underlying anxiety, he felt more willing to acknowledge her frustrations. Cathy was able to tell Robert that she felt isolated and burdened, running the household and caring for their two children alone, unable to work more than part-time because of her responsibilities at home. As we neared the end of the session, Cathy said she felt for the first time that Robert was taking her seriously.

Over several sessions, Cathy felt safe enough to tell Robert that she missed the self-esteem and sense of competence she'd gotten from her full-time job as a nursing administrator. And Robert was finally able to say that he feared turning out like his father, who hadn't been a great provider.

A spirit of mutual respect and cooperation replaced the bickering that had haunted their relationship. They worked hard to keep from attacking each other's tender spots when they discussed problems. And gradually, as their capacity to meet each other's needs increased, their problems shrank. When Cathy realized she was spending excessively in an attempt to make up for feeling deprived by Robert's absence, she decided, on her own, to economize. Robert realized that the family wasn't in as precarious a financial position as he'd believed. He began leaving the office earlier; he saw that he'd been working late not just because of his money worries but to avoid or punish Cathy. He moved beyond believing that it was his duty as a man to be the sole breadwinner and encouraged Cathy to go back to work. These were important subjects Robert and Cathy had stayed away from because they had no language for discussing them.

Robert and Cathy began spending more time together—walking several evenings a week after dinner and pursuing a mutual and long-neglected passion: dancing. Their practice of listening to each other brought them closer and made them stronger. Again and again, I've seen couples surmount seemingly intractable problems when they confront them cooperatively, with an urge to understand rather than defeat each other. When no one wins, both partners take the prize.

More from the O relationship vault: 16 love quotes we love