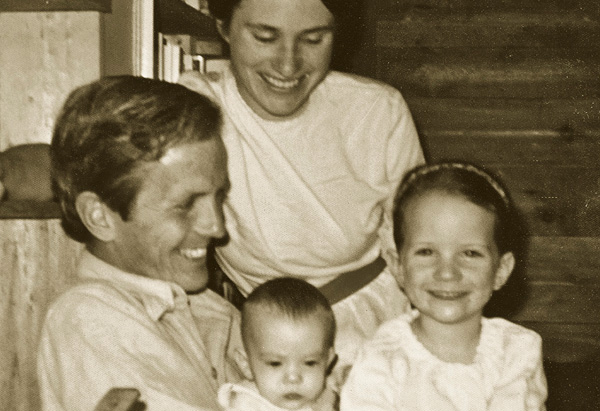

The Colemans at the family dinner table, Maine, 1973.

Charismatic and principled, Melissa Coleman's parents created an idyllic, nonconformist life in rural Maine. And then they paid the price.

We must have asked our neighbor Helen to read our hands that day. Her own hands were the color of onion skins, darkened with liver spots, and ever in motion. Writing, digging, picking, chopping. Opening kitchen cabinets painted with Dutch children in bright embroidered dresses and pointed shoes. Taking out wooden bowls and handing them to my mother, Sue, to put on the patio for lunch. As Mama whooshed out the screen door with hair flowing and baby Heidi on her back, the kitchen breathed chopped parsley and vegetable soup simmered on the stove. The light glowed through the kitchen windows onto the crooked pine floors of the old farmhouse where I stood waiting.It was a charmed summer, that summer of 1975, even more so because we didn't know how peaceful it was in comparison with the one that would follow.

"Ring the lunch bell for Scott-o," Helen called out the window to Mama. She liked to add an o to everyone's name. Eli-o, Suz-o, kiddos for the kids, Puss-o the cat. We were the closest she had to children.

As the bell chimed, Helen took my small hand and turned it upward in hers. The kitchen was warm, but her skin cool and leathery. Mama returned with Heidi as I stood long-hair-braided and 6-years-brave, holding my breath. We knew about Helen that when she didn't have something interesting to say, she'd change the subject. She smoothed my palm with her thumbs and looked down at it, her cropped granite hair holding the dusty smell of old books.

"Tsch, what's this?" she asked of the marks I'd made with Papa's red Magic Marker.

"A map," I told her, proud of the artistry on my fingers. "A map of our farm."

"Pshaw." She tossed my hand aside like an old turnip from the root cellar.

So she read Heidi's palm instead. Heidi was a blue-eyed 2-year-old, "an uncontainable spirit," everyone said. Even she held still, mouth open, breathing heavily, snug in the sling on Mama's back as Helen smoothed out her little fingers.

"Short life line," Helen muttered, bending toward the light from the window, then paused as if catching herself too late.

"What do you mean by short?" Mama asked, brown eyes alert, mother-bird-like. "Thirty, 40 years?"

"Oh, it doesn't mean a thing," Helen said, and began to mutter about the overabundance of tomatoes in the garden.

Eliot hard at work.

Seven years earlier, Helen had read my father Eliot's hands when he and Mama visited, looking for land. Some say hands hold the map of our lives; that the lines of the palm correspond with the heart, head, and soul to create a story unique to each of us. Understanding the lines is an attempt to understand why things happen as they do. Also a quick way to figure out who might make a good neighbor. Helen and her husband, Scott Nearing, authors of the homesteading bible Living the Good Life, wanted young people around who would find the same joys in country living as they did. Their philosophy held the promise of a simple life, far removed from the troubles of the modern world.

"Very strong lines," Helen told Papa that summer of 1968. He had the deepest fate line she'd ever seen, and wide, capable hands. With hands like his, they could do anything. And such a nice-looking couple, too, young and clean-cut—Papa with his sandy tousle of hair, blue eyes, and straight nose, Mama's long, dark hair parted in the middle and kindly chestnut eyes. Shortly after that visit, my parents received a postcard from Helen and Scott offering to sell them the 60 acres next door. That's how we came to be back-to-the-landers on the coast of Maine.

It was 1968, and my parents moved from their home on the campus of Franconia College in New Hampshire, where my father had been teaching, to a makeshift camper on Cape Rosier. There was no mail service, no telephone, no electricity, no plumbing. The site of my future home was only a rise in the forest surrounded by spruce and fir, a cluster of birch and a large ash with its healthy crown of branches. "This seems like a good place to begin," Papa said, standing beside the tree. A self-taught carpenter and woodworker, Papa had never actually built a home before, but he had a book that broke down the process into an easy-to-follow plan; the easy part was there were no electrical wires or pipes to worry about, no refrigerator, washer, dryer, toilet, bath, or other appliances to buy. Food would be stored in the root cellar, accessed by a trapdoor from the kitchen, and the bathroom was an A-frame outhouse located in the woods at the edge of the clearing. And he was doing it all by hand. "Ever thought of getting a chain saw?" a visitor once asked innocently. "We'd rather do without and work more slowly in peace," Papa had replied in his affably militant manner. "A home of our own, at last," Mama sighed. Young and in love and both from blue-blooded families—"fahncy people," Mama liked to joke—my parents hoped to make their way without concern for Social Registers and Harvard degrees; they were shuffling off the shell of the past to grow a future of their own making. They didn't want to be hippies in the traditional sense, having no interest in drugs or communes; rather what appealed to them at the deepest level was the sentiment espoused in Walden by Henry David Thoreau: "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately."

When I was born, Mama carried me on her chest or back with a cloth sling while she worked in the garden or the kitchen and carried drinking water the quarter mile from the spring to the house. After the gift boxes of Pampers from her parents ran out, she put me in plastic panties over safety-pinned cloth diapers that she washed by hand in the ocean and hung to dry in the sun, augmenting the diapers with the same dried peat moss we used for toilet paper in the outhouse. We had no savings account, trust fund, or health insurance policy, no house in town to fall back on. We were living the way much of the world actually lives—even if it seemed weird to some of the locals. On the plus side, we didn't have phone, water, or electrical bills, health insurance premiums, or a mortgage, car payment, or any other monthly payment for that matter. No one could come shut off our utilities and take away our home.

Later Papa would admit that choosing this lifestyle was hard. "We never had any doubts that homesteading was worth it, but at first we didn't realize self-sufficiency means 19th-century primitivism."

THE VEGETABLE GARDEN, the sign at the end of our drive said, ORGANICALLY GROWN, with the vegetables in season listed beneath: carrots, lettuce, tomatoes, zucchini. Past a gravel parking lot, the driveway thinned to a grassy lane curving around the orchard and down a gentle slope to a wood-timbered stand with wet-pebble shelves full of fresh produce for sale. Customers and farmworkers came and went as the surrounding gardens ripened beneath the pale disk of midday sun and cicadas thrummed regular as your pulse. On the rise by an overarching ash tree sat our small house, its slanted roof and front windows like eyes looking across the greenhouse and gardens below. By 1973, thanks partly to two newspaper articles about us and our unusual lifestyle, the farm stand was drawing ever more summer folk from the surrounding towns, bringing earnings of $3,600, which beat Papa's projections by $400. Papa saw in this success our financial security, albeit at the expense of our privacy. "They wanted to see how the freaks live, I suppose," Mama had told the reporter. Afterward she installed a PRIVATE sign on the front door to deter such curiosity in the future.

"Very strong lines," Helen told Papa that summer of 1968. He had the deepest fate line she'd ever seen, and wide, capable hands. With hands like his, they could do anything. And such a nice-looking couple, too, young and clean-cut—Papa with his sandy tousle of hair, blue eyes, and straight nose, Mama's long, dark hair parted in the middle and kindly chestnut eyes. Shortly after that visit, my parents received a postcard from Helen and Scott offering to sell them the 60 acres next door. That's how we came to be back-to-the-landers on the coast of Maine.

It was 1968, and my parents moved from their home on the campus of Franconia College in New Hampshire, where my father had been teaching, to a makeshift camper on Cape Rosier. There was no mail service, no telephone, no electricity, no plumbing. The site of my future home was only a rise in the forest surrounded by spruce and fir, a cluster of birch and a large ash with its healthy crown of branches. "This seems like a good place to begin," Papa said, standing beside the tree. A self-taught carpenter and woodworker, Papa had never actually built a home before, but he had a book that broke down the process into an easy-to-follow plan; the easy part was there were no electrical wires or pipes to worry about, no refrigerator, washer, dryer, toilet, bath, or other appliances to buy. Food would be stored in the root cellar, accessed by a trapdoor from the kitchen, and the bathroom was an A-frame outhouse located in the woods at the edge of the clearing. And he was doing it all by hand. "Ever thought of getting a chain saw?" a visitor once asked innocently. "We'd rather do without and work more slowly in peace," Papa had replied in his affably militant manner. "A home of our own, at last," Mama sighed. Young and in love and both from blue-blooded families—"fahncy people," Mama liked to joke—my parents hoped to make their way without concern for Social Registers and Harvard degrees; they were shuffling off the shell of the past to grow a future of their own making. They didn't want to be hippies in the traditional sense, having no interest in drugs or communes; rather what appealed to them at the deepest level was the sentiment espoused in Walden by Henry David Thoreau: "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately."

When I was born, Mama carried me on her chest or back with a cloth sling while she worked in the garden or the kitchen and carried drinking water the quarter mile from the spring to the house. After the gift boxes of Pampers from her parents ran out, she put me in plastic panties over safety-pinned cloth diapers that she washed by hand in the ocean and hung to dry in the sun, augmenting the diapers with the same dried peat moss we used for toilet paper in the outhouse. We had no savings account, trust fund, or health insurance policy, no house in town to fall back on. We were living the way much of the world actually lives—even if it seemed weird to some of the locals. On the plus side, we didn't have phone, water, or electrical bills, health insurance premiums, or a mortgage, car payment, or any other monthly payment for that matter. No one could come shut off our utilities and take away our home.

Later Papa would admit that choosing this lifestyle was hard. "We never had any doubts that homesteading was worth it, but at first we didn't realize self-sufficiency means 19th-century primitivism."

THE VEGETABLE GARDEN, the sign at the end of our drive said, ORGANICALLY GROWN, with the vegetables in season listed beneath: carrots, lettuce, tomatoes, zucchini. Past a gravel parking lot, the driveway thinned to a grassy lane curving around the orchard and down a gentle slope to a wood-timbered stand with wet-pebble shelves full of fresh produce for sale. Customers and farmworkers came and went as the surrounding gardens ripened beneath the pale disk of midday sun and cicadas thrummed regular as your pulse. On the rise by an overarching ash tree sat our small house, its slanted roof and front windows like eyes looking across the greenhouse and gardens below. By 1973, thanks partly to two newspaper articles about us and our unusual lifestyle, the farm stand was drawing ever more summer folk from the surrounding towns, bringing earnings of $3,600, which beat Papa's projections by $400. Papa saw in this success our financial security, albeit at the expense of our privacy. "They wanted to see how the freaks live, I suppose," Mama had told the reporter. Afterward she installed a PRIVATE sign on the front door to deter such curiosity in the future.

Sue and Lissie in the strawberry patch.

From the time Heidi was old enough to walk, age 1½ to my 5, I took responsibility for her education in survival. The two of us were always outside, naked and barefoot, dancing on the blanket of apple blossoms, skipping along wooded paths, catching frogs at the pond, eating strawberries and peas from the vine, and running from the black twist of garter snakes in the grass. We lay in the shade under the ash tree, gazing up at the crown of leaves and listening to the sounds of the farm—birds calling, goats bleating, chattering of customers at the farm stand, and whispers of tree talk. There was human talk, too—about our farm. It was a bit more excitement than the locals could appreciate when, for example, one of our apprentices rode nude on a hay wagon through the sleepy—but not sleepy enough—town of Harborside. Earlier that summer, another article had appeared, this one a harder look at a movement that was becoming an increasingly controversial topic. The reporter commented that while many back-to-the-landers were serious about the move to the country, others "are leftovers from the escape culture of the '60s who were chiefly interested in smoking marijuana and sitting on the porch talking philosophy."

"Self-sufficiency," the article also noted, "proves too difficult for many. Marital stresses, for example, are exaggerated in isolated areas around the country."

Certainly, our isolated tribe was not immune.

On a humid-hot Saturday near the end of July 1976, the gardens were bustling as usual with apprentices and customers and vegetables needing to be picked. Baby Clara was strapped to Mama's back in Heidi's old sling, sleeping mouth-open as Mama cooked lunch, skin glowing and tan from summer. Our grandmother was coming to visit, and Mama needed time to clean the house, to hide from her mother-in-law the chaos her life had become in the past year. The scores of apprentices, visitors, and customers competed with the never-ending demands of the farm, leaving little time for family. Mama worried about Papa's hyperactive thyroid and about his having had breakfast that morning with Bess, one of the young and beautiful apprentices. Then there was mud that had been tracked in from the gardens, piles of laundry waiting to be washed by hand, and Heidi and me running around the small kitchen pulling each other's hair and screaming.

"One more scream, and you're out," Mama yelled, her mind tumbling over itself.

"Pull my hair, and you'll die," I said to Heidi.

She pulled my braid. I screamed.

"Out." Mama pointed to the screen door, sweat shining on her forehead from the heat of the wood cookstove. Around the stone patio of the farmhouse the daylilies panted their orange tongues in the heat. Rain had fallen the night before, and the air was heavy, as if waiting to rain again.

"I'm going to the woodshed," I said, marching away across the yard and climbing up the woodshed ladder to my perch in the loft. Heidi followed me, reaching up the ladder that she was afraid to climb alone. "Uppie."

"No," I said, but after a while she came back again with a little red boat in her hands.

"Come an' play with me," she begged.

"No," I said. "I'm busy."

Sometime after that I heard Mama calling. "Lissie!" She peeked up from below. "Where's Heidi?"

"I don't know."

"Well, come down and say hello to your grandmother."

My body unbent and shuffled backward down the ladder. It was a little cooler below, but no breeze. The swing hung motionless from the ash tree. I listened for words from the leaves. Nothing.

Then I heard Mama's scream.

A couple of apprentices were sitting in the cool of the gravel pit by the road when someone came running over from the campground.

"Heidi's fallen in the pond!"

I remember the silhouette of a woman coming over the rise from the garden.

"There you are," she said. Was it Bess? Nancy? Michelle? One of our apprentices, but which one? She bent down to put her hands on my shoulders. Her eyes were not right, too bright.

"Self-sufficiency," the article also noted, "proves too difficult for many. Marital stresses, for example, are exaggerated in isolated areas around the country."

Certainly, our isolated tribe was not immune.

*****

On a humid-hot Saturday near the end of July 1976, the gardens were bustling as usual with apprentices and customers and vegetables needing to be picked. Baby Clara was strapped to Mama's back in Heidi's old sling, sleeping mouth-open as Mama cooked lunch, skin glowing and tan from summer. Our grandmother was coming to visit, and Mama needed time to clean the house, to hide from her mother-in-law the chaos her life had become in the past year. The scores of apprentices, visitors, and customers competed with the never-ending demands of the farm, leaving little time for family. Mama worried about Papa's hyperactive thyroid and about his having had breakfast that morning with Bess, one of the young and beautiful apprentices. Then there was mud that had been tracked in from the gardens, piles of laundry waiting to be washed by hand, and Heidi and me running around the small kitchen pulling each other's hair and screaming.

"One more scream, and you're out," Mama yelled, her mind tumbling over itself.

"Pull my hair, and you'll die," I said to Heidi.

She pulled my braid. I screamed.

"Out." Mama pointed to the screen door, sweat shining on her forehead from the heat of the wood cookstove. Around the stone patio of the farmhouse the daylilies panted their orange tongues in the heat. Rain had fallen the night before, and the air was heavy, as if waiting to rain again.

"I'm going to the woodshed," I said, marching away across the yard and climbing up the woodshed ladder to my perch in the loft. Heidi followed me, reaching up the ladder that she was afraid to climb alone. "Uppie."

"No," I said, but after a while she came back again with a little red boat in her hands.

"Come an' play with me," she begged.

"No," I said. "I'm busy."

Sometime after that I heard Mama calling. "Lissie!" She peeked up from below. "Where's Heidi?"

"I don't know."

"Well, come down and say hello to your grandmother."

My body unbent and shuffled backward down the ladder. It was a little cooler below, but no breeze. The swing hung motionless from the ash tree. I listened for words from the leaves. Nothing.

Then I heard Mama's scream.

A couple of apprentices were sitting in the cool of the gravel pit by the road when someone came running over from the campground.

"Heidi's fallen in the pond!"

I remember the silhouette of a woman coming over the rise from the garden.

"There you are," she said. Was it Bess? Nancy? Michelle? One of our apprentices, but which one? She bent down to put her hands on my shoulders. Her eyes were not right, too bright.

"Come with me," she said. "Let's go into the farmhouse." She took my hand and pulled me up to the patio and through the screen door. It slammed behind us. The house was hotter than outside, the cookstove still burning low.

"Come sit here and let's read a book," she said.

"Where's Mama?"

"She's down at the pond."

"Where's Papa?"

"He's down there, too."

"Where's Heidi?"

"Down at the pond."

"I want to go," I said.

"No, you have to stay here," she said.

"I want to go check on Heidi."

"No," she said. But after a while, it seemed I was alone.

I slipped onto the path toward the pond. I walked slowly. "By the time I get there, everything will be okay," I said to myself. Up through the path in the woods came the sound of Mama wailing Heidi's name.

Then I was behind the woodshed with Papa in the dusk of late afternoon. He was holding a blanketed shape in his arms and rocking back and forth, crying in a way I'd never seen before. The afternoon sun burned the tops of the pointed trees around the clearing.

"But Papa," I said. "But Papa, you've got to uncover her face. She can't breathe."

"Lissie," he said. "Heidi is dead."

But Heidi had to be okay.

I didn't mean it when I said she would die.

She had to be okay so I could help her up the ladder next time.

Around the farm the light began to fade, and the daylilies closed up like the fleshy fingers of praying hands.

When the inexplicable happens, everyone wants to find a culprit. Where was the mother? The father? Many blamed our lifestyle, hippies living on a communal farm. "It's because they were heathens, because they didn't abide—they had it coming, living like that," some said. The attending sheriff has since passed on, and the files from that year burned in a fire, so I don't know for sure what the law thought, but as if we didn't have enough pain, my parents were blamed for the accident by the moral world at large—especially Papa, he being the man in charge. Papa said it was the little red boat Heidi must have carried down to the pond and set afloat. One of our farm apprentices said she was the kind of child who wasn't afraid of anything. Another thought it was the black crow that hung around the farm that spring, a single crow being an omen of death in the family. Mama usually says it was the rain. She didn't worry about us girls playing by the pond because it wasn't that deep during the dry months of summer. But when it rained, the pond filled and turned black as the water caught in barrels under the eaves.

As for me, I was sure it was my fault. For days I sat in the loft repeating Heidi's names to myself in a litany, a song to call her back to me.

"Heds, Ho, Hi, Heidi-didi, Heidi-Ho, Hodie."

I sang and sang, but she never came to the foot of that ladder again.

It's said that on the Hebrew Day of Atonement, a goat was sent off to perish in the wilderness, carrying the sins of the people on its back. A scapegoat, and the thread tied around the goat's neck was red for sin and guilt, red like Heidi's boat.

"Come sit here and let's read a book," she said.

"Where's Mama?"

"She's down at the pond."

"Where's Papa?"

"He's down there, too."

"Where's Heidi?"

"Down at the pond."

"I want to go," I said.

"No, you have to stay here," she said.

"I want to go check on Heidi."

"No," she said. But after a while, it seemed I was alone.

I slipped onto the path toward the pond. I walked slowly. "By the time I get there, everything will be okay," I said to myself. Up through the path in the woods came the sound of Mama wailing Heidi's name.

Then I was behind the woodshed with Papa in the dusk of late afternoon. He was holding a blanketed shape in his arms and rocking back and forth, crying in a way I'd never seen before. The afternoon sun burned the tops of the pointed trees around the clearing.

"But Papa," I said. "But Papa, you've got to uncover her face. She can't breathe."

"Lissie," he said. "Heidi is dead."

But Heidi had to be okay.

I didn't mean it when I said she would die.

She had to be okay so I could help her up the ladder next time.

Around the farm the light began to fade, and the daylilies closed up like the fleshy fingers of praying hands.

When the inexplicable happens, everyone wants to find a culprit. Where was the mother? The father? Many blamed our lifestyle, hippies living on a communal farm. "It's because they were heathens, because they didn't abide—they had it coming, living like that," some said. The attending sheriff has since passed on, and the files from that year burned in a fire, so I don't know for sure what the law thought, but as if we didn't have enough pain, my parents were blamed for the accident by the moral world at large—especially Papa, he being the man in charge. Papa said it was the little red boat Heidi must have carried down to the pond and set afloat. One of our farm apprentices said she was the kind of child who wasn't afraid of anything. Another thought it was the black crow that hung around the farm that spring, a single crow being an omen of death in the family. Mama usually says it was the rain. She didn't worry about us girls playing by the pond because it wasn't that deep during the dry months of summer. But when it rained, the pond filled and turned black as the water caught in barrels under the eaves.

As for me, I was sure it was my fault. For days I sat in the loft repeating Heidi's names to myself in a litany, a song to call her back to me.

"Heds, Ho, Hi, Heidi-didi, Heidi-Ho, Hodie."

I sang and sang, but she never came to the foot of that ladder again.

It's said that on the Hebrew Day of Atonement, a goat was sent off to perish in the wilderness, carrying the sins of the people on its back. A scapegoat, and the thread tied around the goat's neck was red for sin and guilt, red like Heidi's boat.

The last time I saw Helen, she read my hands, of course. I'd returned to the farm for the summer of 1995, lost in the way of those living at home in their 20s, seeking something in the past that might mend me. My sister Clara was there, too, seven years younger but an old soul, and we were on a pilgrimage down the path to see the woman who'd been a symbolic grandmother to us.

Clara and I found Helen in the greenhouse, age 91, active as ever, onion-skin hands still in constant motion, pruning and tying up tomato plants, continuing to work even as she took stock of us, these few remaining children from the past. As a way of greeting, Helen reached out and clasped my hand in a leathery grasp so similar to the one in her old kitchen 20 years earlier. There was still the dusky smell of books in her short granite hair, the puffiness under her eyes and chin as she looked down, the clucking of her tongue on the roof of her mouth.

"How old are you?" she asked, pressing the pad of my thumb.

"Twenty-six," I said, feeling quite ancient.

"Young," she said. "Young for your years. At that age I'd already met Scott-o, was already started on my life. What are you doing now?"

"Not sure," I confessed, lacking the skill to bullshit someone who would surely see right through it.

"Well at least you're in possession of yourself." She nodded and gave me back my hand, again leaving the reading undone.

So she read Clara's instead, commenting, I think, that her career line was rather weak. Clara rolled her eyes, resigned to her current fate of joblessness. She would go on to have a family and a successful organic farm of her own, but that was still years away.

Helen simply clicked her tongue.

"Your life is only just begun," she said to Clara. "The lines of the hand can grow and change, you know."

I didn't fully understand what she meant then, but I do now.

Life is not just about the lines we've been given, but what we do with them. By looking back, I can see a pattern in the lines of my hand, the threads of my life. Within that pattern lies the secret to weaving my own future.

Adapted from the memoir This Life Is in Your Hands: One Dream, Sixty Acres, and a Family Undone, by Melissa Coleman, to be published by HarperCollins this month.

4 healthy ways to grieve

Clara and I found Helen in the greenhouse, age 91, active as ever, onion-skin hands still in constant motion, pruning and tying up tomato plants, continuing to work even as she took stock of us, these few remaining children from the past. As a way of greeting, Helen reached out and clasped my hand in a leathery grasp so similar to the one in her old kitchen 20 years earlier. There was still the dusky smell of books in her short granite hair, the puffiness under her eyes and chin as she looked down, the clucking of her tongue on the roof of her mouth.

"How old are you?" she asked, pressing the pad of my thumb.

"Twenty-six," I said, feeling quite ancient.

"Young," she said. "Young for your years. At that age I'd already met Scott-o, was already started on my life. What are you doing now?"

"Not sure," I confessed, lacking the skill to bullshit someone who would surely see right through it.

"Well at least you're in possession of yourself." She nodded and gave me back my hand, again leaving the reading undone.

So she read Clara's instead, commenting, I think, that her career line was rather weak. Clara rolled her eyes, resigned to her current fate of joblessness. She would go on to have a family and a successful organic farm of her own, but that was still years away.

Helen simply clicked her tongue.

"Your life is only just begun," she said to Clara. "The lines of the hand can grow and change, you know."

I didn't fully understand what she meant then, but I do now.

Life is not just about the lines we've been given, but what we do with them. By looking back, I can see a pattern in the lines of my hand, the threads of my life. Within that pattern lies the secret to weaving my own future.

Adapted from the memoir This Life Is in Your Hands: One Dream, Sixty Acres, and a Family Undone, by Melissa Coleman, to be published by HarperCollins this month.

4 healthy ways to grieve

Photo: Courtesy of Melissa Coleman