Op-Ed: Reimagining Suffrage Through the Power of Black Women

Women of the 19th Century were unable to own property, divorce, file legal claims, or even speak in public. Many of the early suffragists were Quakers, some initially ambivalent about voting rights but staunch supporters of women’s equality. The principal spearheads were also abolitionist activists who united with Black men and women around emancipation tied to a movement of universal suffrage. They gathered at a convention in Seneca Falls, NY in 1848, considered the official launching of the women's suffrage movement. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was among the few men allowed to speak to the body, but Black women were not invited, a reflection of the racist patriarchy that impacted the women of that period.

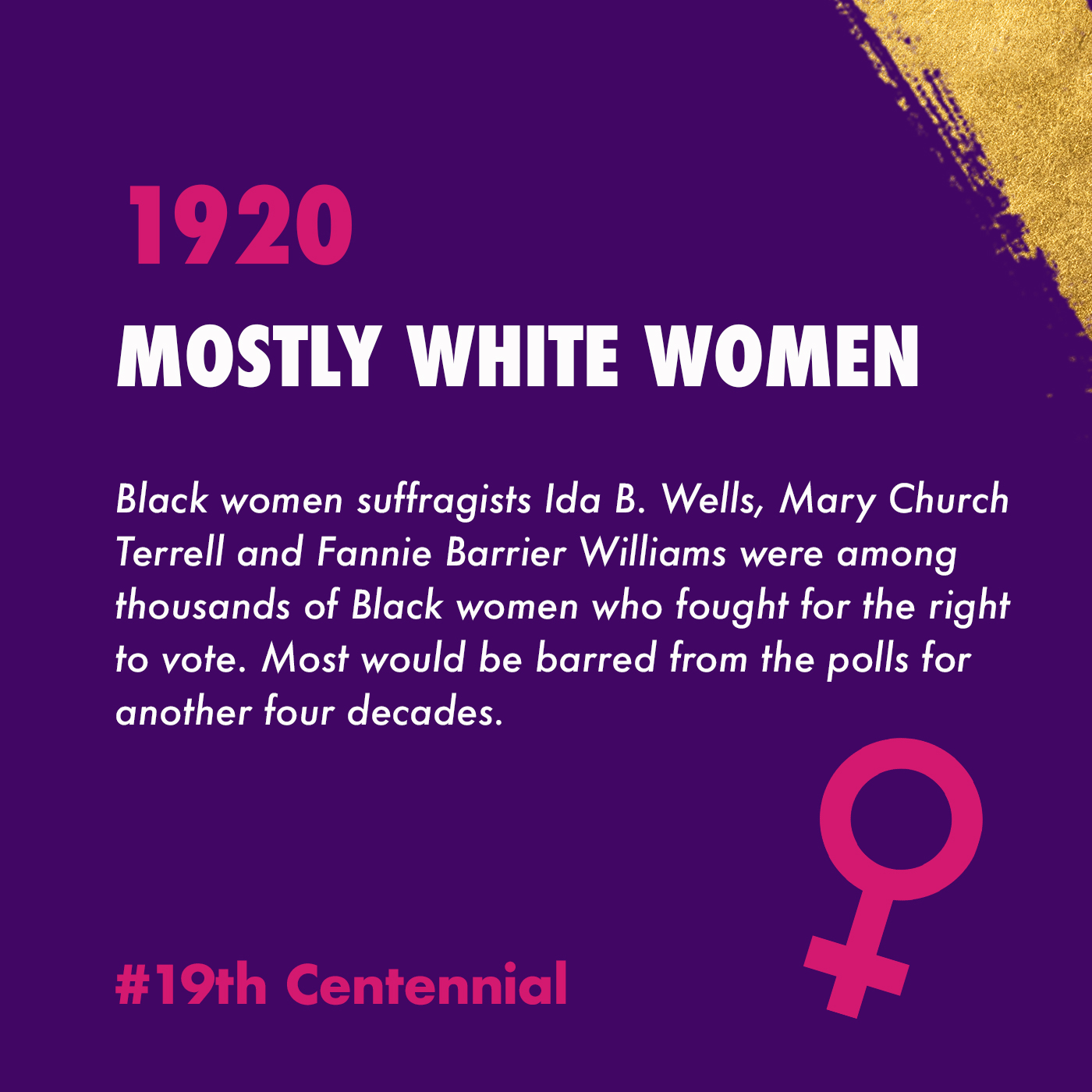

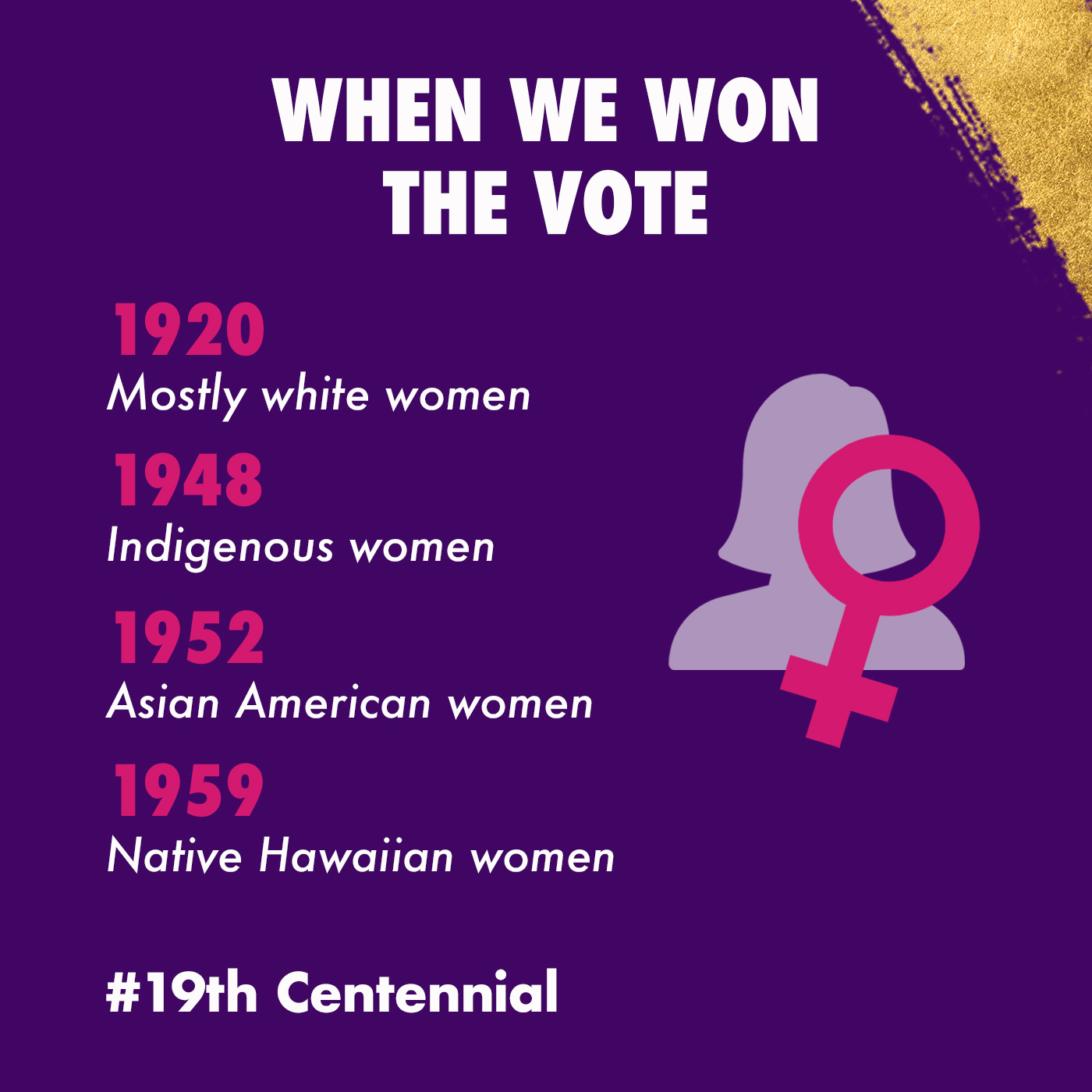

Somewhere between the Civil War and Reconstruction, White women took a metaphoric vote. Narrow White interests won. This followed in quick succession of a trilogy of equality amendments (13th ending slavery, 14th guaranteeing equal protection, and 15th granting Black men voting rights). White suffragists made a choice between the continued push for universal suffrage and alignment with their sisters of the confederacy. Festooned in the symbolic color white, they embraced a cause devoid of racial justice and empowerment. Getting the vote became an end, as opposed to an opening to the creation of real democratic change.

Look no further than the historical landscape of that period. Congressional approval of the Act in 1919 coincided with Red Summer, a tumultuous reign of White terror and lynching in Black communities across the country. One year after the 19th Amendment was adopted in 1921, racist mobs set ablaze Tulsa, Okla., decimating what was revered as Black Wall Street.

Black women embraced suffrage with intersectional advocacy linked to the broad sweep of human rights – anti-lynching, literacy, economic empowerment, sharecropper land rights and the establishment of a radical Black press, led by many Black women suffragists.

As we mark the centennial of the 19th Amendment, let’s also pay tribute to our icons and a reimagined suffrage movement that continues today.

Sojourner Truth. Harriet Tubman. Ida B. Wells. Shirley Chisholm. Rosa Parks. Like household names, these stalwarts, spanning generations, never acted alone. They were among uncounted women warriors whose contributions were erased or untold. They collectively fought, challenged and devised strategies to empower themselves; created women’s clubs, educational campaigns, farm and economic cooperatives and faith institutions.

They stood on the shoulders of nameless suffrage pioneers who joined with their men to resist and carry the torch for all people – Native Americans, Mexican and Chinese immigrants and even Irish indentured servants. Then and now, Black women have refused to relinquish claims to their bodies, voices and choices.

Although the record does not exist, we can surmise that Black women’s fight to command their destiny began when they landed on these shores 401 years ago. That they survived, a sustained struggle ensued over decades and centuries leading up to ratification of women’s voting rights. Though passed over and omitted, their suffrage campaigns continued in different forms, morphed into the civil rights era and passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 which finally, for the first time, delivered the franchise to Black people in the South where the masses of Black people resided.

We build on that truth by redefining suffrage beyond the limited act of casting a ballot. For Black women, the narrative is rooted in telling herstory, celebrating her perseverance and unerasing the achievements of yesterday and the possibilities for the future.

Black girl magic, more than a slogan that brands our beauty and resilience, comes honestly. Imagine our ancestors, enslaved but never owned, passing on that ethos to our grandmothers. Many of them bent but unbowed, understood that just making do was not good enough. Somehow, they made a way out of no way, creating spaces to stretch and flex their muscles on behalf of their children, their men and the larger tribe called community. They bequeathed that strength to the next generations who helped define and reimagine the narrative of Black women’s suffrage that we witness today.

Through it all, Black women have soared even when detractors and opponents would erase our achievements. Those were the building blocks of the early suffrage movement. It emerged, not out of the right to vote, but the charge to be full citizens.

FIVE UNSUNG SUFFRAGISTS

Following are words from powerful unsung women suffragists. Spanning over a century, their contributions are reflective of the toil, courage and vision that Black women bring to a reimagined suffrage movement. Most of these women can’t claim household name status in the traditional suffrage roll call. But their noble stories have helped write our legacy.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) – Publisher of the first Black newspaper Provincial Freeman, which she published from Canada after fleeing her home in Washington to escape the sweeps of the Fugitive Slave Act. She later returned home and received her law degree from Howard University and opened one of the first multi-racial schools in the United States, mostly educating emancipated girls. Her urging to Frederick Douglass and other men leading the abolition movement was to take on work that translated into action.

“We should do more and talk less...” “It is better to wear out than to rust out.”

We have been holding conventions for years — we have been assembling together and whining over our difficulties and afflictions, passing resolutions on resolutions to any extent,” she wrote.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) – Born in Baltimore, the prolific poet and lecturer is believed to be the first Black woman to publish short story fiction. A fierce abolitionist and suffragist, she rendered an impassioned oratory to the leading suffrage group National Woman’s Rights Convention in New York.

“We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.” She also called out the contradictions of White feminists.“[They]...may be divided into three classes, the good, the bad, and the indifferent. The good would vote according to their convictions and principles; the bad, as dictated by preju[d]ice or malice; and the indifferent will vote on the strongest side of the question, with the winning party.”

Mary Church Terrell (1863- 1954) – Educator, writer, founder and president of the National Association of Colored Women, the forerunner to the NAACP, and a major driver of Black suffragist activism. Among the first women to earn a college degree, she often lamented the dual burden of womanhood and Blackness.

“Nobody wants to know a colored woman’s opinion about her own status [or] that of her group. When she dares express it, no matter how mild or tactful..., it is called ‘propaganda,’ or is labeled ‘controversial.'”

Charlotta Amanda Spears Bass (1874 – 1969) – The first Black woman to own a newspaper in the United States, she served as publisher-editor of the Los Angeles-based California Eagle from 1912 to 1952. She was a passionate campaigner against police brutality, housing discrimination and voter repression and transformed that activism into political action as the first African-American woman nominated Vice President, as a candidate of the Progressive Party. In one of her “On the Sidewalk” columns, Bass wrote:

“WOMEN! WOMEN! WOMEN! Particularly Negro Women, this call comes to you! It is up to us to DO something about our position in the body politic of this nation. Let us be aware that we have a glorious history in our land...Many are the stories of heart rending courage that the Negro women of the slave period have handed down to us...They were the mothers of a hundred rebellions, all of which our standard history texts have conveniently forgotten. Yet black women have a tradition which they must not forget and which they must not fail."

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917 – 1977) – A self-educated woman who was forced to trade a seat in the school room for sharecropping in the field. She was jailed, beaten, fired, threatened but never deterred from her activism on behalf of sharecroppers, women and rural communities. She launched Mississippi Freedom Summer which helped engage the nation in the eventual passage of the Voting Rights Act. As the founder of the Mississippi Democratic Freedom Party, she took on The Democratic Party’s 1964 Convention in Atlantic City, demanding to be seated as state delegates:

“All of this is on account we want to register, to become first-class citizens, and if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives are threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings in America?”

Excerpted from

Gwen McKinney, a Washington, DC-based communications strategist is the creator of a public

engagement initiative Suffrage. Race. Power. - Black Women Unerased and the founder of

McKinney & Associates the first Black and woman-owned communications firm in the nation's

capital that expressly promotes social justice policy.

Excerpted from

Gwen McKinney, a Washington, DC-based communications strategist is the creator of a public

engagement initiative Suffrage. Race. Power. - Black Women Unerased and the founder of

McKinney & Associates the first Black and woman-owned communications firm in the nation's

capital that expressly promotes social justice policy.