Sold into Slavery

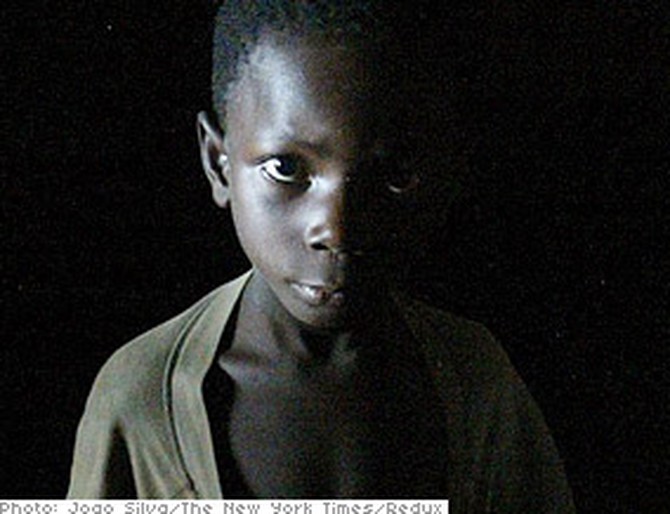

In October 2006, Oprah was reading The New York Times when she saw a picture of a 6-year-old child slave named Mark. For months, she was haunted by the look in Mark's eyes, so Oprah decided to send Oprah Show correspondent Lisa Ling on a 7,000-mile journey to Ghana to find him.

When Lisa first got the assignment, she was shocked to learn the statistics about child slavery in the West African country —which is roughly the size of Oregon. It is estimated that one in every four children in Ghana work as child laborers, Lisa says.

When Lisa first got the assignment, she was shocked to learn the statistics about child slavery in the West African country —which is roughly the size of Oregon. It is estimated that one in every four children in Ghana work as child laborers, Lisa says.

Lisa says many children in Ghana are sold into labor by their own parents. Many of these child slaves—some as young as 4 years old—endure severe beatings, and their work is so back-breaking that their bodies are severely overdeveloped for their young age, Lisa says.

One of the most dangerous jobs for child slaves is working on fishing boats. Seven days a week, 14 hours a day, the "fishing children" are ordered to risk their lives, Lisa says. Beginning each day at 4:30 a.m., the children—many of whom don't know how to swim—are forced to paddle long distances, dive into frigid waters and pull heavy fishing nets from lakes. Lisa says if all goes well, the children pull them up and collect the fish. "But sometimes the nets get caught, and that's when it becomes very, very dangerous," she says.

One of the most dangerous jobs for child slaves is working on fishing boats. Seven days a week, 14 hours a day, the "fishing children" are ordered to risk their lives, Lisa says. Beginning each day at 4:30 a.m., the children—many of whom don't know how to swim—are forced to paddle long distances, dive into frigid waters and pull heavy fishing nets from lakes. Lisa says if all goes well, the children pull them up and collect the fish. "But sometimes the nets get caught, and that's when it becomes very, very dangerous," she says.

When Lisa arrives in Ghana, she joins Eric Peasah from the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Eric and Lisa visit a small village where she meets 59-year-old Napoleon, the father of 22 children.

Napoleon says he had to figure out a way to support his large family, so when a fisherman offered to pay about $20 per child, he agreed to sell nine of them. After laboring for more than two years, Napoleon's children were rescued from their life of slavery.

Now with help from IOM, Napoleon can better support his family. His 14-year-old son Never - who was sold at age eight or nine - says he doesn't think his father knew how bad life would be for him and his siblings.

"They would ask me to go into the river, and I said the place is very deep, and I would say the weather is too cold. They used to force me to go. When I refused, they beat me with paddles," Never says. "They treat me very badly. Like not giving me food. Giving me no clothes. And where to sleep is very difficult." Many of the children are sent into slavery without knowing how to swim, and Never says he saw more than five of his friends drown.

Napoleon says he had to figure out a way to support his large family, so when a fisherman offered to pay about $20 per child, he agreed to sell nine of them. After laboring for more than two years, Napoleon's children were rescued from their life of slavery.

Now with help from IOM, Napoleon can better support his family. His 14-year-old son Never - who was sold at age eight or nine - says he doesn't think his father knew how bad life would be for him and his siblings.

"They would ask me to go into the river, and I said the place is very deep, and I would say the weather is too cold. They used to force me to go. When I refused, they beat me with paddles," Never says. "They treat me very badly. Like not giving me food. Giving me no clothes. And where to sleep is very difficult." Many of the children are sent into slavery without knowing how to swim, and Never says he saw more than five of his friends drown.

Since being rescued and reunited with his family, Never has thrived. Within just two years, he learned to speak English. "It's so incredible to see what can happen when a kid is given a chance," Lisa says. "He didn't speak a word of English [two years before], and now he's back here and his English is awesome."

Lisa asks Never to join Eric and her on a mission to rescue other child slaves, so he can show the world the way he was forced to live. She says she was surprised when Never accepted. "If you think about it, he agreed to take us to the place where he was held captive, he was abused, and he was forced to work," Lisa says. "But there was just this wisdom about Never that was so impressive ... he became very committed to take us."

Lisa asks Never to join Eric and her on a mission to rescue other child slaves, so he can show the world the way he was forced to live. She says she was surprised when Never accepted. "If you think about it, he agreed to take us to the place where he was held captive, he was abused, and he was forced to work," Lisa says. "But there was just this wisdom about Never that was so impressive ... he became very committed to take us."

Since 2002, Eric's team has rescued more than 600 fishing children from slavery. He says most of them come from the central region of the country and then taken hundreds of miles north to the Lake Volta region, where they are forced to work. After a treacherous 10-hour drive, Eric, Lisa and Never must board a ferry that will take them to the remote islands where the children are being held.

Eric says because the area where the children live is so far away from their homes, it's hard for their parents to even know where they are. This distance also contributes to the parents' ignorance of the conditions their children are living in. "We're talking about people who don't have a lot of resources, so they can't exactly take a road trip and go visit their kids," Lisa says.

Eric says because the area where the children live is so far away from their homes, it's hard for their parents to even know where they are. This distance also contributes to the parents' ignorance of the conditions their children are living in. "We're talking about people who don't have a lot of resources, so they can't exactly take a road trip and go visit their kids," Lisa says.

On the island, Lisa finds children working before the sun even rises. In the pitch-dark, she sees four boys with no shoes or life preservers make their way onto the cold lake—their job is to collect the fish captured by their master's nets. Most adults would find the job physically demanding, yet the children must do this grueling work even when they are sick. "It is no good at all," Never says. "It is dangerous."

Lisa and Never see children working hard to paddle a boat alone. "The master is sleeping at home," Never says. Away from their "owner," the children are able to speak openly about what their lives are like. They tell Lisa that they eat only once a day, at 7 a.m., and they are routinely beaten.

"They've lived lives of adults for so many years, you know? They totally lose their childhood," Lisa says. "It was interesting to watch the brotherhood and the relationships that they establish with each other. Because the four boys that we had been following, none of them were biological siblings. But when you ask them 'Who is this?' they say, 'My brother.' It's the only family they have."

Lisa says it is very important not to demonize the fishermen, despite how they allegedly treat the children. "Many of the fishermen were fishing children themselves. This has been going on in Ghana for decades. It's really part of the culture," Lisa says. When Eric, IOM members or the Ghanaian government tell the fishermen they should stop buying children, they meet with resistance. "[The fishermen] say, 'Well, we used to work as fishing children ourselves.' And Eric says, 'That doesn't make it right.' So the challenge really is changing the culture," Lisa says.

Lisa and Never see children working hard to paddle a boat alone. "The master is sleeping at home," Never says. Away from their "owner," the children are able to speak openly about what their lives are like. They tell Lisa that they eat only once a day, at 7 a.m., and they are routinely beaten.

"They've lived lives of adults for so many years, you know? They totally lose their childhood," Lisa says. "It was interesting to watch the brotherhood and the relationships that they establish with each other. Because the four boys that we had been following, none of them were biological siblings. But when you ask them 'Who is this?' they say, 'My brother.' It's the only family they have."

Lisa says it is very important not to demonize the fishermen, despite how they allegedly treat the children. "Many of the fishermen were fishing children themselves. This has been going on in Ghana for decades. It's really part of the culture," Lisa says. When Eric, IOM members or the Ghanaian government tell the fishermen they should stop buying children, they meet with resistance. "[The fishermen] say, 'Well, we used to work as fishing children ourselves.' And Eric says, 'That doesn't make it right.' So the challenge really is changing the culture," Lisa says.

Rescuing Ghana's child slaves is not easy. Eric has a list of 25 children that the IOM would like to liberate, but first, he must convince the fishermen who "own" these boys and girls to agree.

Eric begins negotiations by appealing to the men's softer sides, Lisa says. Then, he offers them incentives like new nets and fishing equipment that would decrease the need for child labor. Occasionally, the IOM also helps the fishermen change career paths and find new ways to support their families.

During this rescue mission, negotiations get off to a rough start. Lisa and Eric encounter a fisherman who owns four children, but he refuses to set them free.

Then, they begin to have more luck. Eric convinces the masters of many young children to let them go. "I can only imagine what's going through their minds right now," Lisa says. "I'm sure they're a little traumatized by what's going on over here."

Moments after being rescued, the children are given plates piled high with food. After surviving for years on just one meal a day, Lisa says the children go back for seconds and thirds. She also notices that they are starting to smile again. It's a familiar scene for Never, who still remembers the happiness he felt the day he was rescued.

At the end of the mission, Eric and his team manage to rescue 21 of the 25 children on the list.

Eric begins negotiations by appealing to the men's softer sides, Lisa says. Then, he offers them incentives like new nets and fishing equipment that would decrease the need for child labor. Occasionally, the IOM also helps the fishermen change career paths and find new ways to support their families.

During this rescue mission, negotiations get off to a rough start. Lisa and Eric encounter a fisherman who owns four children, but he refuses to set them free.

Then, they begin to have more luck. Eric convinces the masters of many young children to let them go. "I can only imagine what's going through their minds right now," Lisa says. "I'm sure they're a little traumatized by what's going on over here."

Moments after being rescued, the children are given plates piled high with food. After surviving for years on just one meal a day, Lisa says the children go back for seconds and thirds. She also notices that they are starting to smile again. It's a familiar scene for Never, who still remembers the happiness he felt the day he was rescued.

At the end of the mission, Eric and his team manage to rescue 21 of the 25 children on the list.

The children begin the long journey back to Ghana's central region to be reunited with their families. Many of them haven't seen their parents in years.

Before the fishing children can return home, they are taken to a rehabilitation clinic where IOM counselors teach them English, as well as basic nutrition and hygiene. They will stay at the clinic for two months. "You can't exactly drop a kid back off into their villages because the parents are the very ones who gave the children up in the first place," Lisa says. "They have to be educated about the fact that sending kids to these [fishing] villages is wrong."

Once the children are settled, Lisa and Eric go in search of their families. With only photos of the children to guide them, they ask villagers for help. Finally, they track down one boy's mother, who says she sold her son to a fisherman so that she could afford to take her husband to the hospital when he was deathly ill.

Lisa and Eric also find the mother of another boy, who was sold into slavery—along with two siblings—when he was just 4 years old. She says she had no other way to support her family after her husband died.

After learning about her son's dangerous living conditions, Lisa says she could see that his mother was embarrassed and full of regret. "I truly don't believe that the parents had any idea of how their child was living," Lisa says. "They are promised not only money, but the fishermen promise that they'll take care of the kids. ... Communication is very limited, so they really just don't know."

Before the fishing children can return home, they are taken to a rehabilitation clinic where IOM counselors teach them English, as well as basic nutrition and hygiene. They will stay at the clinic for two months. "You can't exactly drop a kid back off into their villages because the parents are the very ones who gave the children up in the first place," Lisa says. "They have to be educated about the fact that sending kids to these [fishing] villages is wrong."

Once the children are settled, Lisa and Eric go in search of their families. With only photos of the children to guide them, they ask villagers for help. Finally, they track down one boy's mother, who says she sold her son to a fisherman so that she could afford to take her husband to the hospital when he was deathly ill.

Lisa and Eric also find the mother of another boy, who was sold into slavery—along with two siblings—when he was just 4 years old. She says she had no other way to support her family after her husband died.

After learning about her son's dangerous living conditions, Lisa says she could see that his mother was embarrassed and full of regret. "I truly don't believe that the parents had any idea of how their child was living," Lisa says. "They are promised not only money, but the fishermen promise that they'll take care of the kids. ... Communication is very limited, so they really just don't know."

Two days after the children were taken to the clinic, Lisa returns with some of their families. She says she's overwhelmed by the changes she sees in them. The young boys who were afraid to smile just days before are now singing and stomping their feet.

When the families are brought inside the classroom, the mood suddenly shifts. At first, Lisa says the children seem excited to see their parents, but after a few moments, reality sets in. "I think a lot of them realize that they don't really know their parents anymore," Lisa says.

Some embrace their parents, while others sit quietly at their desks. The boy who was sold when he was 4 years old refuses to go to his mother. Eric says he's still angry with her.

Although Lisa's trip ends on a bittersweet note, she says she finds comfort in knowing that these children can have a better tomorrow. "If God permits, I can be a scientist, a news reader...anything at all," Never says. "I can be a president, too."

When the families are brought inside the classroom, the mood suddenly shifts. At first, Lisa says the children seem excited to see their parents, but after a few moments, reality sets in. "I think a lot of them realize that they don't really know their parents anymore," Lisa says.

Some embrace their parents, while others sit quietly at their desks. The boy who was sold when he was 4 years old refuses to go to his mother. Eric says he's still angry with her.

Although Lisa's trip ends on a bittersweet note, she says she finds comfort in knowing that these children can have a better tomorrow. "If God permits, I can be a scientist, a news reader...anything at all," Never says. "I can be a president, too."

Of all the topics that Lisa has covered for The Oprah Show—from prison life to dangerous gangs—she says this is her best work yet.

Lisa says she was struck by how focused these former child slaves are on getting an education. "They are so hungry to learn because they've never had a day of school in their lives," she says. "It was really interesting to see 17-year-olds in the same classroom as 6-year-olds because they all have to learn the basics."

Although Lisa's main goal was to help rescue these boys and girls from their dangerous living conditions, she also wanted to give them something they hadn't had in years—hugs and affection. Lisa gets emotional when she remembers how one producer gave one of the boys a disposable toothbrush from his backpack. "He put it in his pocket," Lisa says. "He just kept looking down at it and touching it because it was the only possession that he probably had ever had."

"There's so much hope [in Ghana]," she says. "It really inspires me that [if you] give a kid a chance, they won't disappoint."

Lisa says she was struck by how focused these former child slaves are on getting an education. "They are so hungry to learn because they've never had a day of school in their lives," she says. "It was really interesting to see 17-year-olds in the same classroom as 6-year-olds because they all have to learn the basics."

Although Lisa's main goal was to help rescue these boys and girls from their dangerous living conditions, she also wanted to give them something they hadn't had in years—hugs and affection. Lisa gets emotional when she remembers how one producer gave one of the boys a disposable toothbrush from his backpack. "He put it in his pocket," Lisa says. "He just kept looking down at it and touching it because it was the only possession that he probably had ever had."

"There's so much hope [in Ghana]," she says. "It really inspires me that [if you] give a kid a chance, they won't disappoint."

When Lisa set out to rescue Mark, the child slave Oprah saw in The New York Times, she discovered that someone had beat her to it. Who stepped up to save this little boy? A mother of four from Missouri!

During a weekend trip to New York City, Pam and her husband Randy came across the same article that haunted Oprah for months. Pam says that as she read about Mark, she began weeping. "My heart was on the floor," she says. "That article was just so powerful. [My husband and I] both looked at each other and we were like, 'We've got to do something.'"

As soon as she got home, Pam e-mailed the New York Times reporter who wrote the article, Sharon LaFraniere. Two weeks later, she had the name of a man in Ghana who could help. George, a district school official from that region, told Pam that he could rescue Mark, but the child would need a place to live.

Pam's brother-in-law helped her contact the Village of Hope, an orphanage in Ghana. They agreed to take in Mark, as well as six other child slaves. With the help of family and friends, Pam raised enough money to rescue seven fishing children—Mark and six others.

During a weekend trip to New York City, Pam and her husband Randy came across the same article that haunted Oprah for months. Pam says that as she read about Mark, she began weeping. "My heart was on the floor," she says. "That article was just so powerful. [My husband and I] both looked at each other and we were like, 'We've got to do something.'"

As soon as she got home, Pam e-mailed the New York Times reporter who wrote the article, Sharon LaFraniere. Two weeks later, she had the name of a man in Ghana who could help. George, a district school official from that region, told Pam that he could rescue Mark, but the child would need a place to live.

Pam's brother-in-law helped her contact the Village of Hope, an orphanage in Ghana. They agreed to take in Mark, as well as six other child slaves. With the help of family and friends, Pam raised enough money to rescue seven fishing children—Mark and six others.

What spurred Pam to take action after reading The New York Times? She says it was both maternal instinct and personal tragedy. Seven years ago, Pam's son Jansen died from an undetected heart defect. The tragic loss changed her and her husband forever, she says.

After learning about Mark, she says she would lie in bed at night and wonder if Mark was safe or if that was the night something terrible would happen to him. "I just had this haunting that never left me," she says.

Thanks to Pam's persistence, Mark and the six other fishing children were set free just days before Christmas. Two weeks later, Pam and her daughter flew halfway around the world to meet them at the Village of Hope. Now, Pam calls them "the magnificent seven."

"They're just little survivors that have been out on their own," she says. "And they still have strength left to rebuild their lives."

Pam spent a week with the children, and by the end, she says they were calling her "Mama Pam." At night, she says she asked George, the man who orchestrated the rescue, to wish them a special goodnight. "Every night we would say, 'George, tell them they are safe. Tell them they never have to leave. They can live here as long as they want. We will take care of them,'" she says. "Every night [they reacted as if] they had heard it for the first time."

After learning about Mark, she says she would lie in bed at night and wonder if Mark was safe or if that was the night something terrible would happen to him. "I just had this haunting that never left me," she says.

Thanks to Pam's persistence, Mark and the six other fishing children were set free just days before Christmas. Two weeks later, Pam and her daughter flew halfway around the world to meet them at the Village of Hope. Now, Pam calls them "the magnificent seven."

"They're just little survivors that have been out on their own," she says. "And they still have strength left to rebuild their lives."

Pam spent a week with the children, and by the end, she says they were calling her "Mama Pam." At night, she says she asked George, the man who orchestrated the rescue, to wish them a special goodnight. "Every night we would say, 'George, tell them they are safe. Tell them they never have to leave. They can live here as long as they want. We will take care of them,'" she says. "Every night [they reacted as if] they had heard it for the first time."

Mark is now safe and sound at the Village of Hope Orphanage in Ghana. Although Mark has only been there for about six weeks, he's already learned a few words in English and is adjusting well. "I wasn't happy in my village," he says. "I like it here."

Mark shares a bedroom with other children who were rescued by Pam. For the first time in their lives, these boys and girls are sleeping in beds and using a shower.

Pam says that if she can help a child, anyone can. "There's nothing more exciting than to think you're changing somebody's life," she says.

"I've interviewed thousands of people," Oprah tells Pam. "Famous people, rich people...but never has anybody deserved a standing ovation more than you today."

Oprah hopes that the people who hear Pam's story will also be inspired to follow their hearts. "The next time you see a story and the story grabs your heart and it haunts you, you'll think about Pam and what one woman can do to make a difference."

Mark shares a bedroom with other children who were rescued by Pam. For the first time in their lives, these boys and girls are sleeping in beds and using a shower.

Pam says that if she can help a child, anyone can. "There's nothing more exciting than to think you're changing somebody's life," she says.

"I've interviewed thousands of people," Oprah tells Pam. "Famous people, rich people...but never has anybody deserved a standing ovation more than you today."

Oprah hopes that the people who hear Pam's story will also be inspired to follow their hearts. "The next time you see a story and the story grabs your heart and it haunts you, you'll think about Pam and what one woman can do to make a difference."

Although parents of former child slaves are now educated about the dangers their children faced, some worry that poverty might tempt them to sell their children again. Lisa says the government of Ghana is working to break that cycle. Although any child in Ghana who wants to attend school must pay, the government is waiving some school fees and offering incentives to parents not to sell their children, Lisa says.

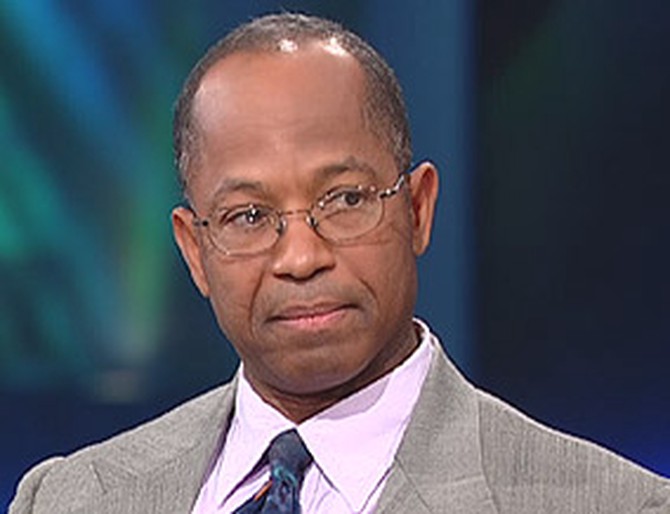

Richard Danziger - the head of counter-trafficking at IOM - says the government of Ghana doesn't have enough resources to fight the problem on its own. He says IOM uses donation money to pay for salaries for counselors, to aid in the rescues of children and to fund the rehabilitation period the children undergo.

Richard estimates that the number of children still enslaved in Ghana is in the high hundreds to low thousands. "This has been going on for decades," he says. "What has started as a sort of apprenticeship has now moved into what we call child trafficking or a form of slavery - just through the change in society, through the extra poverty."

IOM has received many calls and contributions to help the child slaves. Richard says the U.S. State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration funds IOM's program in Ghana, but it isn't enough money to help all the children. Richard says that the more contributions IOM receives, the more children it can help. "Ninety-three percent of the kids we've helped so far, they are back with their families, which is where children should be," Richard says.

Richard Danziger - the head of counter-trafficking at IOM - says the government of Ghana doesn't have enough resources to fight the problem on its own. He says IOM uses donation money to pay for salaries for counselors, to aid in the rescues of children and to fund the rehabilitation period the children undergo.

Richard estimates that the number of children still enslaved in Ghana is in the high hundreds to low thousands. "This has been going on for decades," he says. "What has started as a sort of apprenticeship has now moved into what we call child trafficking or a form of slavery - just through the change in society, through the extra poverty."

IOM has received many calls and contributions to help the child slaves. Richard says the U.S. State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration funds IOM's program in Ghana, but it isn't enough money to help all the children. Richard says that the more contributions IOM receives, the more children it can help. "Ninety-three percent of the kids we've helped so far, they are back with their families, which is where children should be," Richard says.

Ghana isn't the only country where children are forced to work. Jean-Robert Cadet, who is now a college graduate, husband and father, says he grew up as a nameless child slave in Haiti. After his mother died, Jean-Robert says his father abandoned him and he became a restavec. Meaning "stay with," the term refers to children in Haiti who live as unpaid domestic servants.

Jean-Robert says he never knew his birthday or age—and, like many restavecs, he never even had a name. "I was the first to get up in the morning and the last to go to bed at night," he says. "From the minute I woke up, the chores never stopped. I cleared the table after they ate. If there's some leftover food, that's what I ate."

Jean-Robert says he was one of many restavec children in Haiti—and even now, there are hundreds of thousands in that country. "When you go to Haiti, you will see children living on a landfill," he says. "At Christmastime, the only toy they have is a used condom, and they're blowing it and playing with it like a balloon."

Jean-Robert says he never knew his birthday or age—and, like many restavecs, he never even had a name. "I was the first to get up in the morning and the last to go to bed at night," he says. "From the minute I woke up, the chores never stopped. I cleared the table after they ate. If there's some leftover food, that's what I ate."

Jean-Robert says he was one of many restavec children in Haiti—and even now, there are hundreds of thousands in that country. "When you go to Haiti, you will see children living on a landfill," he says. "At Christmastime, the only toy they have is a used condom, and they're blowing it and playing with it like a balloon."

When he was a teenager, Jean-Robert's owners moved to the United States, and with no way to survive on his own, Jean-Robert followed them. "They loaned me their name in order for me to come to the United States to be a slave for them in their home in New York," he says.

But when his owners realized it was illegal to keep him home from school, a door opened for Jean-Robert. He started high school, where a teacher took an interest and began tutoring him. "I loved it. He showed me affection. In a way, he restored some humanity in me," Jean-Robert says. "And then when my owner discovered that I was going to school full-time, I was no longer useful to them. I was kicked out."

Once Jean-Robert finished high school, he realized he really could do something with his life. "As a child in Haiti, one of my duties was to shine everybody's shoes twice a day, and it's a very dusty country. And the owner would say, 'You'll never be anything but a shoeshine boy,'" he says. "And I thought that's the profession that they had chosen for me—until I discovered education. Until I was able to obtain that high school diploma."

After high school Jean-Robert joined the U.S. Army and attended college under the G.I. Bill. Soon, he graduated with a bachelor's degree in international affairs.

But when his owners realized it was illegal to keep him home from school, a door opened for Jean-Robert. He started high school, where a teacher took an interest and began tutoring him. "I loved it. He showed me affection. In a way, he restored some humanity in me," Jean-Robert says. "And then when my owner discovered that I was going to school full-time, I was no longer useful to them. I was kicked out."

Once Jean-Robert finished high school, he realized he really could do something with his life. "As a child in Haiti, one of my duties was to shine everybody's shoes twice a day, and it's a very dusty country. And the owner would say, 'You'll never be anything but a shoeshine boy,'" he says. "And I thought that's the profession that they had chosen for me—until I discovered education. Until I was able to obtain that high school diploma."

After high school Jean-Robert joined the U.S. Army and attended college under the G.I. Bill. Soon, he graduated with a bachelor's degree in international affairs.

With his degree in hand, Jean-Robert decided it was time to pay a visit to the woman with whom he used to live. "I said to her, 'We're going to have a talk.' I said, 'This time I'm going to talk. You listen,'" he says. "And I said, 'Do you remember when you removed your shoe, you hit me across the face? I still have the scar. Do you see it?' And then she started crying. And then I put my bachelor's degree in international affairs ... in front of her. I said, 'You always wanted me to be a shoeshine boy.' I said, 'You see, I'm not a shoeshine boy.' And then I walked out. And that was the last time I saw her."

Although he has moved on with his life, Jean-Robert says he doesn't think one can ever overcome being a child slave. "It's with you," he says. "Because I believe that your childhood is your foundation."

Now, Jean-Robert returns to Haiti to help rescue children living there as restavecs. To spread the word about their plight, Jean-Robert wrote a book called Restavec: From Haitian Slave Child to Middle-Class American and worked on a documentary about the subject. "I wanted to show this film all over the world so people would know that right next door to the United States we have 300,000 to 400,000 restavec children, children in domestic servitude, domestic slaves," he says.

Until things change in Haiti, Jean-Robert says telling young people about child slavery gives him hope. "All I can do is share their story. Write their story. Knock on doors," he says. "I have not found the right one, but I will keep on knocking."

Although he has moved on with his life, Jean-Robert says he doesn't think one can ever overcome being a child slave. "It's with you," he says. "Because I believe that your childhood is your foundation."

Now, Jean-Robert returns to Haiti to help rescue children living there as restavecs. To spread the word about their plight, Jean-Robert wrote a book called Restavec: From Haitian Slave Child to Middle-Class American and worked on a documentary about the subject. "I wanted to show this film all over the world so people would know that right next door to the United States we have 300,000 to 400,000 restavec children, children in domestic servitude, domestic slaves," he says.

Until things change in Haiti, Jean-Robert says telling young people about child slavery gives him hope. "All I can do is share their story. Write their story. Knock on doors," he says. "I have not found the right one, but I will keep on knocking."

Published 02/09/2007