Roger Ebert Speaks Again

Photo: Jon Kopaloff/Getty Images Entertainment

Even the biggest movie buff would be hard-pressed to find a film more inspiring than Roger Ebert's life story.

Before becoming television's most famous film critic—giving his thumbs up or thumbs down to more than 10,000 movies—Roger was a reporter. He joined the Chicago Sun-Times in 1966 and became the paper's film critic one year later. In 1975, his work earned him the Pulitzer Prize.

That same year, Roger debuted his television show with fellow critic Gene Siskel. Their signature thumbs up, thumbs down review system became such a hit, they trademarked the phrase, "Two thumbs up."

For the next 24 years, Siskel and Ebert were household names. But in 1998, Gene was diagnosed with a brain tumor and died less than a year later. Roger was devastated.

Another blow came in 2002, when Roger was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, which later spread to his salivary glands and jaw. He endured surgery after surgery, and the cancer eventually took Roger's voice. In 2006, he was forced to leave his show after more than 30 years on the air.

Although cancer has left Roger unable to speak, eat or drink, it hasn't slowed him down one bit. More than forty years after he started, his words are as powerful as ever. His reviews are still featured in more than 200 newspapers worldwide, and readers flock to his popular blog.

Before becoming television's most famous film critic—giving his thumbs up or thumbs down to more than 10,000 movies—Roger was a reporter. He joined the Chicago Sun-Times in 1966 and became the paper's film critic one year later. In 1975, his work earned him the Pulitzer Prize.

That same year, Roger debuted his television show with fellow critic Gene Siskel. Their signature thumbs up, thumbs down review system became such a hit, they trademarked the phrase, "Two thumbs up."

For the next 24 years, Siskel and Ebert were household names. But in 1998, Gene was diagnosed with a brain tumor and died less than a year later. Roger was devastated.

Another blow came in 2002, when Roger was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, which later spread to his salivary glands and jaw. He endured surgery after surgery, and the cancer eventually took Roger's voice. In 2006, he was forced to leave his show after more than 30 years on the air.

Although cancer has left Roger unable to speak, eat or drink, it hasn't slowed him down one bit. More than forty years after he started, his words are as powerful as ever. His reviews are still featured in more than 200 newspapers worldwide, and readers flock to his popular blog.

Now cancer-free, Roger's back to his busy schedule. With his wife, Chaz, by his side, Roger often starts his day at a movie screening. "We see anywhere from two to four movies in a day," she says. "I need to be near him so in case he needs anything, I can look and he can give me a signal."

Spend a day with Roger and Chaz.

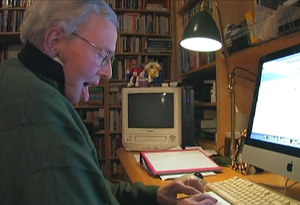

Roger and Chaz communicate through special signals they've developed. If Roger wants Chaz to relay a message to someone, he sometimes writes what he wants to say on a piece of paper. When he has his computer, Roger can type what he wants to say, hit a button and the computer says it for him. When he holds his hand over his heart, he's telling Chaz he loves her.

At mealtimes, Chaz usually eats alone in the dining room. "I don't like to eat in front of him because it just seems kind of cruel since he can no longer eat," she says. "When he lost his jaw, he lost the lower floor of his mouth. And so if he ate, there's nothing to support it."

Roger gets his nourishment about four times a day intravenously. "He has his meals in a gravity drip bag suspended from this IV pole and connected to a tube that goes through a port in his stomach," Chaz says.

Roger says he doesn't miss food as much as he misses the camaraderie of a meal. "However, every now and then, he wants me to eat something that he used to like," Chaz says. "He likes to watch me eat it."

Spend a day with Roger and Chaz.

Roger and Chaz communicate through special signals they've developed. If Roger wants Chaz to relay a message to someone, he sometimes writes what he wants to say on a piece of paper. When he has his computer, Roger can type what he wants to say, hit a button and the computer says it for him. When he holds his hand over his heart, he's telling Chaz he loves her.

At mealtimes, Chaz usually eats alone in the dining room. "I don't like to eat in front of him because it just seems kind of cruel since he can no longer eat," she says. "When he lost his jaw, he lost the lower floor of his mouth. And so if he ate, there's nothing to support it."

Roger gets his nourishment about four times a day intravenously. "He has his meals in a gravity drip bag suspended from this IV pole and connected to a tube that goes through a port in his stomach," Chaz says.

Roger says he doesn't miss food as much as he misses the camaraderie of a meal. "However, every now and then, he wants me to eat something that he used to like," Chaz says. "He likes to watch me eat it."

Roger's struggles and triumphs were captured in a March 2010 Esquire magazine article, which ran with a portrait of Roger's new face. "People ask if I mind about Esquire running that photograph of me looking like this," he says through his computer. "I don't mind at all. Nobody looks perfect. We have to find peace with the way we look and get on with life."

Although there is a reconstruction procedure available, Roger says he's done with surgery. "I'm not going to talk or eat or drink again, so the surgery would only be to patch my face back together," he says. "I don't want to go through that. This is the way I look and my life is happy and productive, so why have any more surgery?"

Although there is a reconstruction procedure available, Roger says he's done with surgery. "I'm not going to talk or eat or drink again, so the surgery would only be to patch my face back together," he says. "I don't want to go through that. This is the way I look and my life is happy and productive, so why have any more surgery?"

When asked what his last words were, Roger says he doesn't remember. "I didn't realize at the time they were going to be my last words. I probably spoke them to Chaz as they wheeled me out to the operating room," he says. "They were probably, 'I love you.' At least, I hope those were my last words."

"On the other hand, they may have been, 'Good morning, doctor,'" Roger jokes.

Though he may not be able to speak in real life, Roger says he often talks in his dreams. "I'm talking all the time," he says. "That's just like I was in life. You could never shut me up."

"On the other hand, they may have been, 'Good morning, doctor,'" Roger jokes.

Though he may not be able to speak in real life, Roger says he often talks in his dreams. "I'm talking all the time," he says. "That's just like I was in life. You could never shut me up."

Still, Roger says his physical limitations have opened him up to wonderful new experiences.

Roger says his memories are more vivid than they've ever been. "Even when I'm awake, I remember things that amaze me. I remember my dad and me driving to the A&W Root Beer stand when I was about 5 and his voice saying, 'A 5-cent beer for the boy,'" he says. "For nights and nights after I lost my ability to drink or taste, I would wake up with my thoughts focused on that little glass mug all frosted with ice."

In his mind, Roger says he could taste that root beer. "I took the taste over and over," he says.

After hearing this story, Roger's brother-in-law helped him appreciate the gift he had received. "I told them I had remembered that day with my father for the first time in 60 years. Johnny asked me if I ever thought about it since. 'No,' I said, 'not even once,'" he says. "Johnny told me, 'It might be that when the Lord took away your drinking, he gave you back that memory.'"

Roger says his memories are more vivid than they've ever been. "Even when I'm awake, I remember things that amaze me. I remember my dad and me driving to the A&W Root Beer stand when I was about 5 and his voice saying, 'A 5-cent beer for the boy,'" he says. "For nights and nights after I lost my ability to drink or taste, I would wake up with my thoughts focused on that little glass mug all frosted with ice."

In his mind, Roger says he could taste that root beer. "I took the taste over and over," he says.

After hearing this story, Roger's brother-in-law helped him appreciate the gift he had received. "I told them I had remembered that day with my father for the first time in 60 years. Johnny asked me if I ever thought about it since. 'No,' I said, 'not even once,'" he says. "Johnny told me, 'It might be that when the Lord took away your drinking, he gave you back that memory.'"

Modern technology has also given Roger a life-changing gift—his voice. A company in Scotland is using cutting-edge technology to take hours of Roger's past movie commentaries and create a new, computerized voice from those clips.

Though it won't be perfect, Roger says he's looking forward to sounding like his old self again. "It's what they call a beta. It still needs improvement, but at least it sounds like me," he says. "When I type anything, this voice will speak whatever I type. When I read something, it will read in my voice. I have got to say, in first grade they said I talked too much. And now I still can."

Watch Roger and Chaz test the voice for the first time.

Chaz hasn't heard her husband's voice since July 1, 2006. She's moved to tears. "It's incredible that that's your voice," she says. "Roger? What do you think?"

"Uncanny," his voice answers. "A good feeling."

Though it won't be perfect, Roger says he's looking forward to sounding like his old self again. "It's what they call a beta. It still needs improvement, but at least it sounds like me," he says. "When I type anything, this voice will speak whatever I type. When I read something, it will read in my voice. I have got to say, in first grade they said I talked too much. And now I still can."

Watch Roger and Chaz test the voice for the first time.

Chaz hasn't heard her husband's voice since July 1, 2006. She's moved to tears. "It's incredible that that's your voice," she says. "Roger? What do you think?"

"Uncanny," his voice answers. "A good feeling."

Chaz and Roger have been married 18 years. Through sickness and health, she has been by Roger's side every step of the way. "I would like to say, from one woman to another, you are incredible," Oprah says. "The reason is this: This woman refused to let him die. Years ago during the early, first operations when everybody was saying it's done, it's over, Chaz called me and said, 'I refuse to let him die.' And she stood by him and has been with him and taken care of him and shown what true love is."

Chaz says the experience has been intense, but she knew she couldn't give up on Roger. "When I married Roger, I knew what an amazing man he was. He is smart. He's funny. He's very respectful of women. He's appreciative of other cultures," she says. "It's hard to find someone like him. And I didn't want to lose him. And I felt almost like I was going a little insane. I was so intense; I just refused to give up on him. If there was anything in my power to help him live, that's what I was going to do."

Chaz says the experience has been intense, but she knew she couldn't give up on Roger. "When I married Roger, I knew what an amazing man he was. He is smart. He's funny. He's very respectful of women. He's appreciative of other cultures," she says. "It's hard to find someone like him. And I didn't want to lose him. And I felt almost like I was going a little insane. I was so intense; I just refused to give up on him. If there was anything in my power to help him live, that's what I was going to do."

Roger has journaled about the lesson he's learned throughout this ordeal. It's one every person can live by:

"I believe that if, at the end of it all, according to our abilities, we have done something to make others a little happier, and something to make ourselves a little happier, that is about the best we can do. To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts. We must try to contribute joy to the world. That is true no matter what our problems, our health, our circumstances. We must try. I didn't always know this, and I am happy that I lived long enough to find it out."

Get Roger's Oscar® picks

Morgan Freeman's role of a lifetime

Best Actor nominee Colin Firth

"I believe that if, at the end of it all, according to our abilities, we have done something to make others a little happier, and something to make ourselves a little happier, that is about the best we can do. To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts. We must try to contribute joy to the world. That is true no matter what our problems, our health, our circumstances. We must try. I didn't always know this, and I am happy that I lived long enough to find it out."

Get Roger's Oscar® picks

Morgan Freeman's role of a lifetime

Best Actor nominee Colin Firth