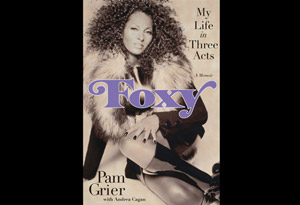

Excerpt from Foxy: My Life in Three Acts

Photo: Hachette Book Group

Chapter 1: Stunt Work

I was snuggled in my mother's arms in the backseat of the old Buick. My dad's Air Force buddy was at the wheel, driving us from Fort Dix Air Force Base to Colorado, where Dad was being transferred. I'd been born into a military family, making my first move by car at three weeks old, since blacks were rarely seen on trains. And, of course, there was no way we could afford to fly, even if planes had been available. I was born in Winston-Salem, where my dad's family lived. My parents had expected their visit to North Carolina to last three to four days before they returned to Colorado, where Mom would give birth to me. But it seemed that between the intense heat, the long hours of relaxation, and the large mouthfuls of ripe, juicy watermelon she ingested, my mom went into early labor with me. She was uncomfortable having her baby in Winston-Salem. She'd wanted to be safe and sound in Colorado when I was born, with her own family around her. Apparently I had other plans.Now Dad was in the passenger seat, riding shotgun, while his buddy drove the old '48 crank Buick with no seat belts, which no one had as yet. In the backseat, the driver's wife was carrying a goldfish in a bowl of water, and Mom was carrying me. As we rode along the New Jersey Turnpike, a car sped down the on-ramp, passed us, and suddenly shot out onto the road right in front of us. As Dad's friend swerved to miss the car cutting us off, our Buick rolled over three times and came to a stop at the side of the turnpike, its wheels beneath it. We all got out. Mom had never let go of me, and everyone in the car walked away without a scratch—except the goldfish, who died from oxygen inhalation. That was my first stunt.

Of course I don't remember that happening. My first memory was in Columbus, Ohio, where my father was stationed at the Air Force base there. I was in diapers, about a year and a half old, and I recall my mother's colorful skirt and the gauzy white strings that hung off the bow of her apron. Her legs looked impossibly long, and I marveled at her wedged shoes that made her taller than she really was. She was at the kitchen sink, and I was on the floor beside her, when I heard an engine roar outside the house. We both turned to look past the black and white Formica kitchen table out into the courtyard to see my dad driving into the garage.

"Daddy's home," my mother practically sang, as I tried to climb up the table leg to see outside. Mom, pregnant with my brother, Rod, hoisted me up onto the kitchen table so I could watch my father get out of the car and come into the house. It makes my mom absolutely insane that I can remember these things in such minute detail from before I was two. But I do. I also remember sitting on the front steps, eating a slice of fresh tomato, and dropping it on the ground when my dad walked toward me. I was standing on shaky legs, my arms raised for him to lift me up, when I slipped on the tomato slice. I bounced once before my dad caught me. Back then, there was no one more amazing and strong in all the world.

My dad, Clarence Grier, was a strappingly handsome man with tremendous strength in his hands. I could literally feel youthful energy shoot through his fingers. He was kind and loving to me, and the scent of his cologne combined with the crisp, starchy smell of his clean Air Force uniform delighted me. A loving, carefree man, he was my mom's hero. He was so light-skinned, he could pass for white, which caused him a lot more trouble than if he had clearly looked black or white. His mom was mixed, and his blue-eyed dad was mixed but looked white, so he never really fit in anywhere.

"Daddy's home," my mother practically sang, as I tried to climb up the table leg to see outside. Mom, pregnant with my brother, Rod, hoisted me up onto the kitchen table so I could watch my father get out of the car and come into the house. It makes my mom absolutely insane that I can remember these things in such minute detail from before I was two. But I do. I also remember sitting on the front steps, eating a slice of fresh tomato, and dropping it on the ground when my dad walked toward me. I was standing on shaky legs, my arms raised for him to lift me up, when I slipped on the tomato slice. I bounced once before my dad caught me. Back then, there was no one more amazing and strong in all the world.

My dad, Clarence Grier, was a strappingly handsome man with tremendous strength in his hands. I could literally feel youthful energy shoot through his fingers. He was kind and loving to me, and the scent of his cologne combined with the crisp, starchy smell of his clean Air Force uniform delighted me. A loving, carefree man, he was my mom's hero. He was so light-skinned, he could pass for white, which caused him a lot more trouble than if he had clearly looked black or white. His mom was mixed, and his blue-eyed dad was mixed but looked white, so he never really fit in anywhere.

Remember the old term mulatto? Today we call it biracial or multicultural, but back then, being a mulatto was a major obstacle. At the base in Columbus, for example, where segregation was at an all-time high, blacks had to live in apartments off base because they were offered substandard living on base. That was where Dad suffered the confusion of his superiors, who thought he was white when they first met him. When we arrived, we had been awarded a lovely place on base to live, because they thought Dad was Caucasian. But before we ever moved in, they discovered their mistake and told us that since we were Negroes, we had to make other living arrangements. Dad felt comfortable living among whites, and the indignity of being asked to move out affected his self-confidence. He had dreamed of going to officer training school. He had what it took, and Mom wanted that for him, too. But he lacked the necessary confidence. He had hit the racial wall so many times, I guess he just gave up, and we lived in an apartment off base that was shockingly inferior to the living quarters on base. In fact, everything was different.

If you lived on base, you had decent facilities, good food, and current entertainment, including movies and music. If you lived off base, the public bus system hardly ever stopped for you, particularly if the back of the bus was full. On base, shuttles took you shopping or wherever else you wanted to go. Off base, you felt the humiliation, embarrassment, and sting of segregation, like when you were shopping with your family and the bus sped right by you, as if you didn't exist. In this era, we had to make sure we didn't look at someone the wrong way—it was a constant tension—or we could end up having our lives threatened. It seemed that while Air Force whites had access to whatever they needed, blacks had to make do, and there was no bucking against the status quo. The makeshift apartments where blacks lived (we called ourselves Negroes back then) were some distance from the base, and if you didn't have a car, you had better have a pair of sturdy legs.

If you lived on base, you had decent facilities, good food, and current entertainment, including movies and music. If you lived off base, the public bus system hardly ever stopped for you, particularly if the back of the bus was full. On base, shuttles took you shopping or wherever else you wanted to go. Off base, you felt the humiliation, embarrassment, and sting of segregation, like when you were shopping with your family and the bus sped right by you, as if you didn't exist. In this era, we had to make sure we didn't look at someone the wrong way—it was a constant tension—or we could end up having our lives threatened. It seemed that while Air Force whites had access to whatever they needed, blacks had to make do, and there was no bucking against the status quo. The makeshift apartments where blacks lived (we called ourselves Negroes back then) were some distance from the base, and if you didn't have a car, you had better have a pair of sturdy legs.

One afternoon—I was about five and my little brother, Rodney, was four—Mom and us kids were carrying shopping bags home from the grocery store. The walk was a few miles, and my mom usually didn't mind it, but it was so hot that day that we were walking from tree to tree, stopping in the shade to catch our breath and drum up the courage to walk under the blistering sun to the next tree. Laden with shopping bags, my mom, dripping with perspiration, looked longingly at a nearly empty bus that drove right past us.

"It's so hot out," I said. "Why won't the bus stop for us, Mom?"

"Because we're Negroes," she said.

Mom was gasping for air, she looked like she was ready to pass out, I was beyond uncomfortable, and even my little brother was panting. Another bus, completely empty, sped by us, and then another. When a fourth bus was about to drive on past us, it slowed, pulled over to the side of the road, and stopped. Mom walked cautiously to the stairs as the white bus driver opened the door. She looked in questioningly, glancing at all the empty seats, hoping against hope that we might be able to ride home.

The driver said nothing and neither did my mom. She just hustled us to the back of the bus and we fell onto the seats, breathing heavily. We sat quietly in our private chariot, grateful to be out of the hot sun. Mom knew this man was risking his personal security by picking us up. He obviously had a big heart under that white skin. He never looked at us, and we kept our eyes straight ahead as we neared our apartment complex. Mom told him when we got close to home, and he stopped to let us off.

She knew she was not allowed to speak to him, and she fought the urge to show her appreciation with a light touch on this kind man's shoulder. That could have gotten her into trouble. We faced these kinds of issues every day when the grocery clerk put our change on the counter instead of in our hands to avoid physical contact. How my mom managed to hold on to her dignity in such a condemning and shaming society, where we had to take what we were given, I will never know. But somehow she was able to turn everything around and convince us it was a blessing.

"It's so hot out," I said. "Why won't the bus stop for us, Mom?"

"Because we're Negroes," she said.

Mom was gasping for air, she looked like she was ready to pass out, I was beyond uncomfortable, and even my little brother was panting. Another bus, completely empty, sped by us, and then another. When a fourth bus was about to drive on past us, it slowed, pulled over to the side of the road, and stopped. Mom walked cautiously to the stairs as the white bus driver opened the door. She looked in questioningly, glancing at all the empty seats, hoping against hope that we might be able to ride home.

The driver said nothing and neither did my mom. She just hustled us to the back of the bus and we fell onto the seats, breathing heavily. We sat quietly in our private chariot, grateful to be out of the hot sun. Mom knew this man was risking his personal security by picking us up. He obviously had a big heart under that white skin. He never looked at us, and we kept our eyes straight ahead as we neared our apartment complex. Mom told him when we got close to home, and he stopped to let us off.

She knew she was not allowed to speak to him, and she fought the urge to show her appreciation with a light touch on this kind man's shoulder. That could have gotten her into trouble. We faced these kinds of issues every day when the grocery clerk put our change on the counter instead of in our hands to avoid physical contact. How my mom managed to hold on to her dignity in such a condemning and shaming society, where we had to take what we were given, I will never know. But somehow she was able to turn everything around and convince us it was a blessing.

Instead of touching the bus driver, she said, "Thank you," as they looked into each other's eyes, sharing a moment of grace and true humanity. He drove away, never looking back. She turned to Rodney and me and said, "We just got a beautiful gift. Never forget it. God is taking care of us." And she never mentioned it again.

As a little girl, I wondered what it would have been like to wait for a bus like anyone else, to go into any restroom anywhere, and be welcomed into any restaurant we chose. I imagined Mom saying, "Hey, let's take a break from shopping and go have lunch," like any other citizen of the world. But that was not our world.

When I think back about why we didn't end up feeling inferior every day of our lives, I give credit to my loving family. We were very close, my parents made sure we had good manners and morals, and my mom always had several white friends who were sympathetic to contemporary black issues. While a few white women were still stuck in racial prejudice, most of Mom's friends, the white women who were married to NCOs (noncommissioned officers), never believed the ridiculous and denigrating myths and lies surrounding Negroes.

After all, the men worked in close proximity, whether they were white or black. And Mom's ability to create dress patterns and sew beautiful clothing gave her a special standing among her group of friends. Mom was so good at sewing, they could show her a dress on the cover of Vogue magazine and she could create that very dress and make her friends look classic and rich. My mom's white friends knew that we were good people and that she wanted the same things for us that they wanted for their own children. Today, I see what a great role model my mom was. She didn't believe in prejudice and she didn't want us to grow up hating or fearing white people.

As a little girl, I wondered what it would have been like to wait for a bus like anyone else, to go into any restroom anywhere, and be welcomed into any restaurant we chose. I imagined Mom saying, "Hey, let's take a break from shopping and go have lunch," like any other citizen of the world. But that was not our world.

When I think back about why we didn't end up feeling inferior every day of our lives, I give credit to my loving family. We were very close, my parents made sure we had good manners and morals, and my mom always had several white friends who were sympathetic to contemporary black issues. While a few white women were still stuck in racial prejudice, most of Mom's friends, the white women who were married to NCOs (noncommissioned officers), never believed the ridiculous and denigrating myths and lies surrounding Negroes.

After all, the men worked in close proximity, whether they were white or black. And Mom's ability to create dress patterns and sew beautiful clothing gave her a special standing among her group of friends. Mom was so good at sewing, they could show her a dress on the cover of Vogue magazine and she could create that very dress and make her friends look classic and rich. My mom's white friends knew that we were good people and that she wanted the same things for us that they wanted for their own children. Today, I see what a great role model my mom was. She didn't believe in prejudice and she didn't want us to grow up hating or fearing white people.

In the segregated area of the city where we lived, we could only socialize with other people of color. We couldn't sit beside whites at movies or eat with them in restaurants. We couldn't use public transportation, and it was so bad that just chatting with white people could get us in trouble, so we avoided it.

When we spent time on base, however, our best friends were both black and white kids. We were invited to join them in the sandboxes, in the swimming pool, and on the bike trails. Some bases were more liberal than others, and at our base, the military complex worked hard at creating the "look" of equality. That meant we were allowed to enjoy the company of color-blind friends who accepted us just the way we were. It was an important lesson to learn that not all white people hated us for being different.

Mom went through nursing school during that time so she would have an occupation that felt worthwhile and would help her pick up the financial slack if it was necessary. She believed very strongly that women needed to know they could fend for themselves if push came to shove, such as in case of a death, disablement, or illness. And she could add income to the family coffers. Dad loved his Air Force work, where he focused on aviation, which was his calling. He was an NCO, which meant he had enlisted. He held on to his dream of becoming an officer, but he was holding out until "things" got better. That was the African American mantra—"Waiting for times to get better"—as we tried to envision a world with fewer obstacles, apprehensions, and hostility.

When we spent time on base, however, our best friends were both black and white kids. We were invited to join them in the sandboxes, in the swimming pool, and on the bike trails. Some bases were more liberal than others, and at our base, the military complex worked hard at creating the "look" of equality. That meant we were allowed to enjoy the company of color-blind friends who accepted us just the way we were. It was an important lesson to learn that not all white people hated us for being different.

Mom went through nursing school during that time so she would have an occupation that felt worthwhile and would help her pick up the financial slack if it was necessary. She believed very strongly that women needed to know they could fend for themselves if push came to shove, such as in case of a death, disablement, or illness. And she could add income to the family coffers. Dad loved his Air Force work, where he focused on aviation, which was his calling. He was an NCO, which meant he had enlisted. He held on to his dream of becoming an officer, but he was holding out until "things" got better. That was the African American mantra—"Waiting for times to get better"—as we tried to envision a world with fewer obstacles, apprehensions, and hostility.

Up to the time I was six, when my day-to-day existence would change drastically, I had a bubbly personality and a zest for life. We had no home of our own since we were constantly being transferred from base to base. But I was always eager to laugh and hungry to learn, and I adored the early days when we lived with my grandmother Marguerite, whom we called Marky, and my grandfather Raymundo Parrilla, of Philippine descent, whom we called Daddy Ray. Marky was a music enthusiast, cleaning house to the sounds of Mahalia Jackson, gospel, and Elvis's "Blue Suede Shoes," which she played over and over again. Every day, each family on the block had a pot of vegetables, beans, or black-eyed peas and collard greens simmering on the stove. Food aromas wafted down the street all the time, which gave a homey, warm feeling to the neighborhood.

I was thrilled when Daddy Ray gave me a dime one Saturday so I could go to the movies with a few of my friends and cousins. My aunt Mennon, my mother's sister, had four children, and I recall my excitement when we headed off to the neighborhood movie theater to see Godzilla, a film clearly chosen by the boys.

The truth is that the film could have been about anything under the sun. I wouldn't have cared. It was my first movie, and I was ecstatic over the darkened theater and my very own nickel bag of popcorn that I didn't have to share. There were no segregation restrictions for the kiddie matinee, so we were free to frolic, scream, and munch on candy and popcorn. It felt like an indoor playground where kids could bounce on the seats, yell, giggle, laugh, and play with abandon, reacting to what was on the movie screen.

I was thrilled when Daddy Ray gave me a dime one Saturday so I could go to the movies with a few of my friends and cousins. My aunt Mennon, my mother's sister, had four children, and I recall my excitement when we headed off to the neighborhood movie theater to see Godzilla, a film clearly chosen by the boys.

The truth is that the film could have been about anything under the sun. I wouldn't have cared. It was my first movie, and I was ecstatic over the darkened theater and my very own nickel bag of popcorn that I didn't have to share. There were no segregation restrictions for the kiddie matinee, so we were free to frolic, scream, and munch on candy and popcorn. It felt like an indoor playground where kids could bounce on the seats, yell, giggle, laugh, and play with abandon, reacting to what was on the movie screen.

Our group of about ten kids felt safe, since the older cousins and neighbors watched over us younger kids, and we all cheered and booed in the appropriate places. But when I told the other kids that the monster wasn't real, they refused to believe me.

"His tail was made of rubber," I insisted. "I could tell. I saw the crease."

"It was not!" they said, unwilling to believe that the magic of Hollywood was in play here. They didn't want the monster to be made of rubber, while I was fascinated by rubber monsters with fake tails. I decided then and there that, one day, I would work in the movies in some capacity.

Marguerite and Daddy Ray spent time between their farmhouse in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and a modern cinder-block and brick home in Denver, Colorado, where we stayed sometimes when Dad was stationed nearby. This sleepy, bucolic neighborhood was fashioned in Craftsman style, its streets lined with century-old majestic oak and maple trees. The sidewalks were slabs of granite and redstone, no cement; the structures were built to last. No one had garages then, so everyone parked their Edsels on the streets with no worries about them getting stolen.

In the house, there were chrome faucets in the bathroom, and every time we used the sink, we had to wipe the water spots off the chrome. If we didn't, my grandmother went berserk and raised holy hell, since she was meticulous to a fault. After dinner, the floor had to be swept and the dishes had to be washed, dried, and put away. Then and only then could we sit down to tackle our homework.

"His tail was made of rubber," I insisted. "I could tell. I saw the crease."

"It was not!" they said, unwilling to believe that the magic of Hollywood was in play here. They didn't want the monster to be made of rubber, while I was fascinated by rubber monsters with fake tails. I decided then and there that, one day, I would work in the movies in some capacity.

Marguerite and Daddy Ray spent time between their farmhouse in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and a modern cinder-block and brick home in Denver, Colorado, where we stayed sometimes when Dad was stationed nearby. This sleepy, bucolic neighborhood was fashioned in Craftsman style, its streets lined with century-old majestic oak and maple trees. The sidewalks were slabs of granite and redstone, no cement; the structures were built to last. No one had garages then, so everyone parked their Edsels on the streets with no worries about them getting stolen.

In the house, there were chrome faucets in the bathroom, and every time we used the sink, we had to wipe the water spots off the chrome. If we didn't, my grandmother went berserk and raised holy hell, since she was meticulous to a fault. After dinner, the floor had to be swept and the dishes had to be washed, dried, and put away. Then and only then could we sit down to tackle our homework.

My grandfather had a station wagon and an army jeep for hunting. While Dad taught us to play tennis and other games he enjoyed on the base, Daddy Ray taught us how to survive. As I mentioned, the army bases were sometimes color-blind as to our attending activities and eating good meals. But out in the civilian world, particularly in public school, we had to deal with civil rights, racial prejudice, and the accompanying self-hatred. Daddy Ray wanted us to be prepared. Best of all was my grandparents' farm up in Wyoming, where my grandfather and my grandma specialized in growing sugar beets and raising goats. My favorite place in the world. We went there on weekends. The farmhouse had a big old barn where Daniel, one of my American Indian uncles, lived. Uncle Daniel had a long white braid, and he mainly survived on canned peaches from the farm. He lived to be 107.

The farmhouse had no indoor plumbing, so we used an outhouse that was stocked with corn cobs and a coffee can full of vinegar to disinfect and disguise the smell. Our grandparents had used corn cobs for toilet paper back in the day, but by the time we got there, we had toilet paper, so the corn cobs were just a reminder of days gone by. Since there was no electricity, and it was pitch-dark at night, Daddy Ray set up ropes that we could hold on to that led from the house to the outhouse. We used a kerosene lantern to see our way, and when the wind blew up in swirling gales, if we didn't grasp the rope tightly, we could get blown away.

The farmhouse kitchen was one big room with a slab of slate with a hole in it for the sink. The actual sink was underneath in the form of an enamel basin sitting on a small table. At the end of the table was the pump primer that we would pump a few times to get water flowing from the spigot into the sink. We heated water there for our baths. The farmhouse eventually became the cabin where the men stayed during hunting season. A small slice of heaven on earth, this wonderful farm was precious and charming, and I felt safer and healthier there than anywhere else, even as we dealt with the harsh and sometimes cruel elements of the wild, such as high winds and extreme temperatures from hotter than hot to freezing cold. In fact, the wind-chill factor was so extreme that when it reached up into the higher registers, the force of the gales could actually crack metal.

The farmhouse had no indoor plumbing, so we used an outhouse that was stocked with corn cobs and a coffee can full of vinegar to disinfect and disguise the smell. Our grandparents had used corn cobs for toilet paper back in the day, but by the time we got there, we had toilet paper, so the corn cobs were just a reminder of days gone by. Since there was no electricity, and it was pitch-dark at night, Daddy Ray set up ropes that we could hold on to that led from the house to the outhouse. We used a kerosene lantern to see our way, and when the wind blew up in swirling gales, if we didn't grasp the rope tightly, we could get blown away.

The farmhouse kitchen was one big room with a slab of slate with a hole in it for the sink. The actual sink was underneath in the form of an enamel basin sitting on a small table. At the end of the table was the pump primer that we would pump a few times to get water flowing from the spigot into the sink. We heated water there for our baths. The farmhouse eventually became the cabin where the men stayed during hunting season. A small slice of heaven on earth, this wonderful farm was precious and charming, and I felt safer and healthier there than anywhere else, even as we dealt with the harsh and sometimes cruel elements of the wild, such as high winds and extreme temperatures from hotter than hot to freezing cold. In fact, the wind-chill factor was so extreme that when it reached up into the higher registers, the force of the gales could actually crack metal.

My favorite time of day was the early morning when we would help Daddy Ray in his organic garden. Gardening was the norm in that area, and neighborhood families took great pride in competing with each other. Who could grow the biggest and tastiest squash, pumpkins, cucumbers, and "ter-maters"? Just about every home in this little town had a working garden—they took up at least half of the large yards—and our white and black neighbors traded vegetables, freshly caught fish, and venison to help each other out. As a result, we always had fresh lettuce with Italian dressing and ripe, pungent tomatoes that were blood-red on the inside. We grew our own onions, scallions, radishes, and carrots, and on the far side of my grandparents' house was a big strawberry patch. In the middle of the patch was a tree that bore golden freestone peaches with little clefts in the sides that turned orange when the peaches were ripe. Beside the peach tree were a prolific black walnut tree and a cherry tree, full of dark red bing cherries that weighed the branches down when they were ready for picking.

We ate like royalty back then because everything was fresh. This was before the emergence of the massive supermarkets where we buy our food today. We got our protein from the Korean deli around the corner, where they sold freshly killed chickens and recently caught fish. Some of our neighbors had chickens on their property and a cutoff tree stump for slaughtering them. They would catch a chicken, wring its neck and lay it across the stump, chop off its head like with a guillotine, and drain the blood. Then, to remove the feathers easily, they would drop it into boiling water for a few seconds.

When the men took off on hunting expeditions into the high country of Colorado or Wyoming, they brought back pheasant, game hens, wild turkeys, elks, and antelope. They fished for river catfish, bass, and lake trout, and my grandfather taught us kids to fly-fish. Daddy Ray was obsessed with teaching us to be self-sufficient, and we all had to learn to tie flies onto the hooks with pieces of carpeting and feathers and shiny wool. Then we were taught to cast a fly rod so we could catch German brown, rainbow, and speckled trout. We also took turns learning to steer the fishing boat through the water.

Some of the girls said, "I'm scared, Daddy Ray. I don't know how to steer a boat. I can't."

"You can't be scared," he told them, "or you can't come with me. If something happens to me, you have to be able to bring the boat back to shore." We also loved waterskiing and we needed to steer a boat for that, too. I was always the first in line to learn whatever he showed us.

We ate like royalty back then because everything was fresh. This was before the emergence of the massive supermarkets where we buy our food today. We got our protein from the Korean deli around the corner, where they sold freshly killed chickens and recently caught fish. Some of our neighbors had chickens on their property and a cutoff tree stump for slaughtering them. They would catch a chicken, wring its neck and lay it across the stump, chop off its head like with a guillotine, and drain the blood. Then, to remove the feathers easily, they would drop it into boiling water for a few seconds.

When the men took off on hunting expeditions into the high country of Colorado or Wyoming, they brought back pheasant, game hens, wild turkeys, elks, and antelope. They fished for river catfish, bass, and lake trout, and my grandfather taught us kids to fly-fish. Daddy Ray was obsessed with teaching us to be self-sufficient, and we all had to learn to tie flies onto the hooks with pieces of carpeting and feathers and shiny wool. Then we were taught to cast a fly rod so we could catch German brown, rainbow, and speckled trout. We also took turns learning to steer the fishing boat through the water.

Some of the girls said, "I'm scared, Daddy Ray. I don't know how to steer a boat. I can't."

"You can't be scared," he told them, "or you can't come with me. If something happens to me, you have to be able to bring the boat back to shore." We also loved waterskiing and we needed to steer a boat for that, too. I was always the first in line to learn whatever he showed us.

As primitive as life was on this farm, I loved how people treated each other and how we all shared our crops with our neighbors. It seemed like cities were prohibitively expensive because people tried to make money off of each other instead of lending a helping hand. Out in the farmlands, in contrast, no one went hungry because we traded raspberries for cherries, and tomatoes for corn. I learned how many ears of corn usually grew on a stalk, and Daddy Ray showed me how to dig deep down into the soil to determine if it was rich enough for the crop we wanted to plant.

"The roots of the cornstalks need to be at least four feet in the ground," Daddy Ray told me, "and the stalk will measure about eight to ten feet high. The longer the roots, the more ears of corn it will produce."

We were taught to respect and cherish the earth, something that has stayed with me for my entire life. When I hear the famous Joni Mitchell lyric "They paved paradise and put up a parking lot," I nod my head. I may not have been raised like a privileged city kid with a ton of new clothes and toys, but that means nothing, because when I was growing up, I got to live in paradise.

"The roots of the cornstalks need to be at least four feet in the ground," Daddy Ray told me, "and the stalk will measure about eight to ten feet high. The longer the roots, the more ears of corn it will produce."

We were taught to respect and cherish the earth, something that has stayed with me for my entire life. When I hear the famous Joni Mitchell lyric "They paved paradise and put up a parking lot," I nod my head. I may not have been raised like a privileged city kid with a ton of new clothes and toys, but that means nothing, because when I was growing up, I got to live in paradise.

This is an excerpt from FOXY by Pam Grier, Andrea Cagan. Copyright © 2010 by Pam Grier, Andrea Cagan. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing, New York, NY. All rights reserved.