Overcoming Prejudice

How well do you think you know yourself? Would you be willing to take a 10-minute test that reveals your hidden feelings about people of different races, religious faiths, weights and sexualities? What would you do if the test exposed prejudices you didn't even know you had?

Finding out that you harbor hidden prejudices can be alarming. These guests have hopeful news: With effort, anyone can change the way they think.

Finding out that you harbor hidden prejudices can be alarming. These guests have hopeful news: With effort, anyone can change the way they think.

When he was 13 years old, Matt came out to his family, telling them that he was gay. His mother's response shocked him.

"She said, 'Well, if that's what you believe you cannot live in my house,'" Matt says. "The next thing I knew, I was standing on a street corner alone with the bag that she packed. I felt that I wasn't even worth living on this planet if your own mother can throw you away for something that you can't change, that you can't do anything about."

He says he soon found himself living on the streets in West Hollywood.

"She said, 'Well, if that's what you believe you cannot live in my house,'" Matt says. "The next thing I knew, I was standing on a street corner alone with the bag that she packed. I felt that I wasn't even worth living on this planet if your own mother can throw you away for something that you can't change, that you can't do anything about."

He says he soon found himself living on the streets in West Hollywood.

In West Los Angeles, Tim—a self-described racist—says he spent his teenage years terrorizing his neighborhood through violent crimes. In his 20s, Tim joined the White Aryan Resistance, a neo-Nazi group. Tim says their list of enemies included homosexuals, African-Americans, Hispanics and white liberal "race traitors."

His hatred exploded in a vicious attack on an Iranian couple, whom Tim mistook for Jewish.

The case made headlines, and Tim served a year in jail.

"When you're involved with that sort of a lifestyle … you see the enemy everywhere," he says.

His hatred exploded in a vicious attack on an Iranian couple, whom Tim mistook for Jewish.

The case made headlines, and Tim served a year in jail.

"When you're involved with that sort of a lifestyle … you see the enemy everywhere," he says.

As a homeless teenager in West Hollywood, Matt says he survived by working as a street hustler. While this life was "not easy and it was not pretty," Matt says he didn't think his sexuality would lead someone to want to kill him.

But one day, Matt says, he was sitting in front of a building with three other guys when they heard a group of about a dozen people nearby. "When they said, 'We'll kill the faggots,' I knew we were in trouble," Matt says.

"I got up and ran. I made it to the alley. I went to the ground and they started kicking and beating and stomping. I really thought this was it. I was going to die a homeless kid and for no other reason than I was gay," he says. "The last thing I remember was a boot to my head and I was unconscious."

But one day, Matt says, he was sitting in front of a building with three other guys when they heard a group of about a dozen people nearby. "When they said, 'We'll kill the faggots,' I knew we were in trouble," Matt says.

"I got up and ran. I made it to the alley. I went to the ground and they started kicking and beating and stomping. I really thought this was it. I was going to die a homeless kid and for no other reason than I was gay," he says. "The last thing I remember was a boot to my head and I was unconscious."

When he got out of prison, Tim started a family and set about indoctrinating his son to hate. "His first words were mommy, daddy, Heil Hitler, white power, the n-word," he says. "Instead of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey, it would be pin-the-yellow-star-on-the-Jew." Tim says he even rewarded his son with cookies when he learned new racial slurs.

As his son grew older, Tim says he began to lose faith in the White Aryan Resistance. The tipping point came when Tim's then 3-year old son used the n-word in a grocery store. "It was an enlightening moment for me. Very scary, you know, look what I'm doing to my child."

Tim says he began plotting his exit and left the group. Later, after years of soul-searching and regret, he went to work at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. "I thought that maybe it was a way that I could make amends somehow to hopefully help others to steer clear of that sort of lifestyle."

As his son grew older, Tim says he began to lose faith in the White Aryan Resistance. The tipping point came when Tim's then 3-year old son used the n-word in a grocery store. "It was an enlightening moment for me. Very scary, you know, look what I'm doing to my child."

Tim says he began plotting his exit and left the group. Later, after years of soul-searching and regret, he went to work at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. "I thought that maybe it was a way that I could make amends somehow to hopefully help others to steer clear of that sort of lifestyle."

Matt survived the beating in the alley, and after recovering, he says he moved on with his life. Then, in 1998, when headlines broke about the savage murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard in Wyoming, Matt felt a calling. "What struck me about Matthew Shepard was that the only difference between he and I was that he was dead and I wasn't," he says. "He no longer had a voice that he could use and I still did. I wanted to speak out for all people who suffer intolerance or become victims, and I had to find a way to do that."

Matt also went to work at the Museum of Tolerance, where he met Tim. They talked about where they'd grown up and where they used to hang out, soon realizing they both had spent time in West Hollywood. When Tim recalled the details of a particularly violent evening, "I said, 'You realize who you're sitting across from?" Matt says.

Stunned to be speaking with the man who'd once attacked him, Matt says he abruptly ended the conversation and headed back to work. Reliving that night was painful. "I remember the absolute violence of it," he says. "I really believed that, that was my last night on earth, that their intent was to kill me."

Tim says he'd never forgotten his part in that attack, either. "It was pretty brutal—one of the most brutal things that I've ever done," he says. "I've hurt a lot of people in my life, but for some reason that particular incident stood out all throughout the years."

Matt also went to work at the Museum of Tolerance, where he met Tim. They talked about where they'd grown up and where they used to hang out, soon realizing they both had spent time in West Hollywood. When Tim recalled the details of a particularly violent evening, "I said, 'You realize who you're sitting across from?" Matt says.

Stunned to be speaking with the man who'd once attacked him, Matt says he abruptly ended the conversation and headed back to work. Reliving that night was painful. "I remember the absolute violence of it," he says. "I really believed that, that was my last night on earth, that their intent was to kill me."

Tim says he'd never forgotten his part in that attack, either. "It was pretty brutal—one of the most brutal things that I've ever done," he says. "I've hurt a lot of people in my life, but for some reason that particular incident stood out all throughout the years."

Two weeks after they realized the violent manner in which their lives had intersected years before, Tim was supposed to give a presentation at the Museum of Tolerance for a group of children. "I explained to them that I had done a lot of things in my life," he says. Tim then introduced Matt. "'And this is a former victim of one of my hate crimes.' And I apologized at that moment."

When Tim apologized for the first time, Matt says was so overcome with emotion that he had to leave the room. He then began trying to forgive Tim. "It wasn't overnight, you know. It was a process," he says. "It's a self-serving reason to forgive somebody—I didn't do it so Tim would feel better. I did it so I could heal. In forgiving Tim … and just over time, I realized that there were two different people—the 17-year-old who carried out that act of violence, and the man he is today who is trying to help others."

To test Tim's change of heart, Matt invited him to a barbecue—and didn't tell him that this barbecue was going to be attended by 60 gay men! Tim admits that he felt awkward at first, but that he got over it and a great time.

While he works to educate others about the dangers of hate, Tim says he still deals with the lingering effects of his own destructive past, including the effect it has had on his son.

When Tim apologized for the first time, Matt says was so overcome with emotion that he had to leave the room. He then began trying to forgive Tim. "It wasn't overnight, you know. It was a process," he says. "It's a self-serving reason to forgive somebody—I didn't do it so Tim would feel better. I did it so I could heal. In forgiving Tim … and just over time, I realized that there were two different people—the 17-year-old who carried out that act of violence, and the man he is today who is trying to help others."

To test Tim's change of heart, Matt invited him to a barbecue—and didn't tell him that this barbecue was going to be attended by 60 gay men! Tim admits that he felt awkward at first, but that he got over it and a great time.

While he works to educate others about the dangers of hate, Tim says he still deals with the lingering effects of his own destructive past, including the effect it has had on his son.

When Steven Spielberg's movie Schindler's List was released in 1993, Monika Hertwig went to see the film, "looking for my father," she says. Her father was Amon Goeth, a Nazi officer and commander of the Plaszow concentration camp outside Krakow, Poland. Since age 11, when she found out he was a ruthless murderer, Monika had been searching for answers about her father.

On screen, Monika saw actor Ralph Fiennes portray her father as a sadistic monster, single-handedly responsible for killing thousands of Jews during the Holocaust.

"When I came home I was sick," she says. "Spielberg told me the truth. And for telling me the truth, I attacked him because I didn't want to know everything."

On screen, Monika saw actor Ralph Fiennes portray her father as a sadistic monster, single-handedly responsible for killing thousands of Jews during the Holocaust.

"When I came home I was sick," she says. "Spielberg told me the truth. And for telling me the truth, I attacked him because I didn't want to know everything."

In 1939, Helen Jonas, a young Jewish girl, lived in Poland with her family. "I was 14 when the war broke out," she says. "Within a short time, we were told that we all have to move to the ghetto. Within a couple of months, two SS [officers] walked into our room and took my father away."

Helen's father was killed in the gas chambers at the Belzek death camp. Meanwhile, Helen, her mother and her two sisters were sent to a concentration camp near Krakow. It was there, she says, that Amon Goeth handpicked Helen to become a slave in his house.

"My first job was to iron his shirt. As I'm ironing the shirt, he slapped me so hard on my cheek. He said, 'You stupid Jew. You don't even know how to iron a shirt properly,'" Helen says. "And I started to cry. And he hit me so hard again. In that moment, I realized that I have to grow up. I'm no more child. I'm no more with my mother. I am here, and I have to obey."

Helen's father was killed in the gas chambers at the Belzek death camp. Meanwhile, Helen, her mother and her two sisters were sent to a concentration camp near Krakow. It was there, she says, that Amon Goeth handpicked Helen to become a slave in his house.

"My first job was to iron his shirt. As I'm ironing the shirt, he slapped me so hard on my cheek. He said, 'You stupid Jew. You don't even know how to iron a shirt properly,'" Helen says. "And I started to cry. And he hit me so hard again. In that moment, I realized that I have to grow up. I'm no more child. I'm no more with my mother. I am here, and I have to obey."

Eventually, Monika realized that she wanted to know the truth about her father. Sixty years after the Allied liberation of Plaszow, Monika contacted Helen, asking to meet her in Poland. Helen reluctantly agreed. "Monika sent me a letter, and in the letter she expressed her feelings about how hard it must be for me, but it is hard also for her," Helen says. "And then she said, 'We have to do it. We have to do it for the murdered people.' And I was touched by that sentence."

Helen and Monika met at the Plaszow Memorial Monument, located at the camp where Helen witnessed unimaginable horrors and the place where her mother is buried. Monika finally heard the terrible truth about her father. "He was a living monster. He enjoyed what he was doing," Helen says. "But he did it out of pleasure because I saw his face after killing."

Even after all these years, Monika is still haunted by her mother's statement that she is just like her father. "[I asked], 'Am I better than my father?' She told me, 'You are like him, and you will die like him,'" Monika says. "I was always looking in my life…maybe I'm really like him. But I am not Amon."

"You have a choice," Helen says. "You have a mission."

Helen and Monika met at the Plaszow Memorial Monument, located at the camp where Helen witnessed unimaginable horrors and the place where her mother is buried. Monika finally heard the terrible truth about her father. "He was a living monster. He enjoyed what he was doing," Helen says. "But he did it out of pleasure because I saw his face after killing."

Even after all these years, Monika is still haunted by her mother's statement that she is just like her father. "[I asked], 'Am I better than my father?' She told me, 'You are like him, and you will die like him,'" Monika says. "I was always looking in my life…maybe I'm really like him. But I am not Amon."

"You have a choice," Helen says. "You have a mission."

The home in which Helen was kept a slave, where she says her childhood was stolen, still stands near Krakow. When Helen took Monika there, she says a rush of emotions came flooding back. "I felt the same feeling. Even though the villa is so deteriorated," Helen says. "But I felt like I am living there and the fear that was with me at all times, day and night."

As they stood in the room, Helen recalled how she used to look out her bottom-floor window and envy the people walking to work. "I can't explain to you what this room means to me when I was treated like a criminal," Helen says.

She also remembers Amon Goeth's ominous footsteps every morning, which usually preceded the sound of shooting. "First thing in the morning, he would walk out of the villa, 6:00, and I would hear shooting," Helen says. "He had the urge to kill."

As they stand in the room, Monika struggles with the stories she was told as a child about why her father killed Jews. Helen says those stories were lies. "This is why people are misled and they keep on. If it's repeated like that, then it will happen again. We have to start something different," Helen says.

As they stood in the room, Helen recalled how she used to look out her bottom-floor window and envy the people walking to work. "I can't explain to you what this room means to me when I was treated like a criminal," Helen says.

She also remembers Amon Goeth's ominous footsteps every morning, which usually preceded the sound of shooting. "First thing in the morning, he would walk out of the villa, 6:00, and I would hear shooting," Helen says. "He had the urge to kill."

As they stand in the room, Monika struggles with the stories she was told as a child about why her father killed Jews. Helen says those stories were lies. "This is why people are misled and they keep on. If it's repeated like that, then it will happen again. We have to start something different," Helen says.

Despite the horrors she suffered as a teen, Helen says she has forgiven Amon and everyone else involved. "I must say that forgiveness is mostly a gift to myself in order to be able to live some quality of life and in honor of my parents and all the innocent people that perished so tragically," Helen says.

Helen says that Monika must also let go of the pain she feels. "You have nothing to feel guilty about," she says.

Together, Helen says that she and Monika can convey a powerful message to the world. "That's why we met in Krakow and that's why we're here. To show the world this is no way to live," Helen says. "We have to be understanding of tolerance."

For more information on Helen and Monika's story, visit InheritanceDocumentary.com .

Helen says that Monika must also let go of the pain she feels. "You have nothing to feel guilty about," she says.

Together, Helen says that she and Monika can convey a powerful message to the world. "That's why we met in Krakow and that's why we're here. To show the world this is no way to live," Helen says. "We have to be understanding of tolerance."

For more information on Helen and Monika's story, visit InheritanceDocumentary.com .

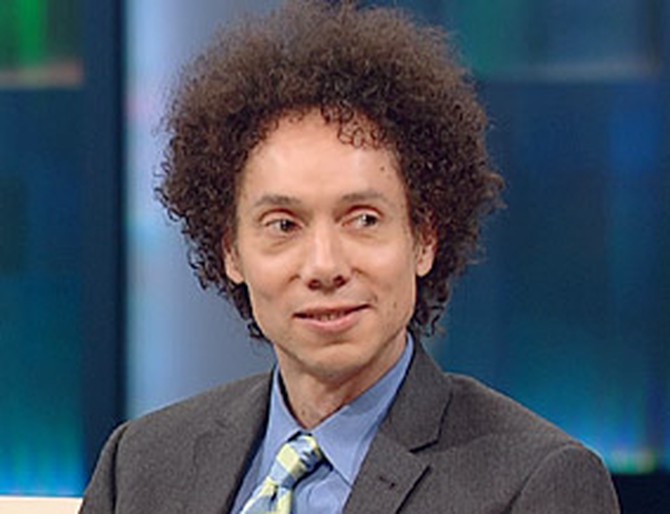

Are you a racist? Most people would deny they have prejudices, but best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell's book, Blink, discusses a fascinating test that actually uncovers a person's hidden biases.

The Implicit Association Test (IAT), developed by professors from Harvard, the University of Virginia and the University of Washington, measures the two levels that all people operate within—the conscious and the unconscious. Malcolm says the conscious level includes "the decisions we make deliberately and things that we're aware of. I chose to wear these clothes. I choose the books I read."

The unconscious level can tell you more about a person's true feelings. "There's another level below the surface which is the kind of stuff that comes out, tumbles out before we have a chance to think about it. Our snap decisions. Our first impressions," Malcolm says. "One of the big ideas in psychology recently has been that level, that second level, is really important in how we behave. How we think and how we feel [are] really important in things like prejudice and discrimination."

What the test has shown, Malcolm says, is that people are not shaping those unconscious feelings themselves. "[They] are a function of the kind of world we live in and the society that we move in," he says.

The Implicit Association Test (IAT), developed by professors from Harvard, the University of Virginia and the University of Washington, measures the two levels that all people operate within—the conscious and the unconscious. Malcolm says the conscious level includes "the decisions we make deliberately and things that we're aware of. I chose to wear these clothes. I choose the books I read."

The unconscious level can tell you more about a person's true feelings. "There's another level below the surface which is the kind of stuff that comes out, tumbles out before we have a chance to think about it. Our snap decisions. Our first impressions," Malcolm says. "One of the big ideas in psychology recently has been that level, that second level, is really important in how we behave. How we think and how we feel [are] really important in things like prejudice and discrimination."

What the test has shown, Malcolm says, is that people are not shaping those unconscious feelings themselves. "[They] are a function of the kind of world we live in and the society that we move in," he says.

Malcolm decided to put himself to the test about his feelings toward African-Americans. He was shocked by his results.

The test told him he had a moderate preference for white people. "In other words, I was biased—slightly biased—against black people … which horrified me because my mom's Jamaican," he says. "The person in my life who [I] … love almost more than anyone else is black, and here I was taking a test, which said, frankly, I wasn't too crazy about black people."

Malcolm took the test again. He found he couldn't "cheat the test" and got the same results. "Those kinds of snap decisions that make up so much discrimination or … our thoughts and feelings, they're a product of the worlds we live in," Malcolm says. "And if you live in a world, as we do, where you … turn on the television and you see a TV show and the crack dealer's always a black guy and the judge is always a white person … those images start to matter. They start to change the way the software in your head works. And that's regardless of what race you are."

The test told him he had a moderate preference for white people. "In other words, I was biased—slightly biased—against black people … which horrified me because my mom's Jamaican," he says. "The person in my life who [I] … love almost more than anyone else is black, and here I was taking a test, which said, frankly, I wasn't too crazy about black people."

Malcolm took the test again. He found he couldn't "cheat the test" and got the same results. "Those kinds of snap decisions that make up so much discrimination or … our thoughts and feelings, they're a product of the worlds we live in," Malcolm says. "And if you live in a world, as we do, where you … turn on the television and you see a TV show and the crack dealer's always a black guy and the judge is always a white person … those images start to matter. They start to change the way the software in your head works. And that's regardless of what race you are."

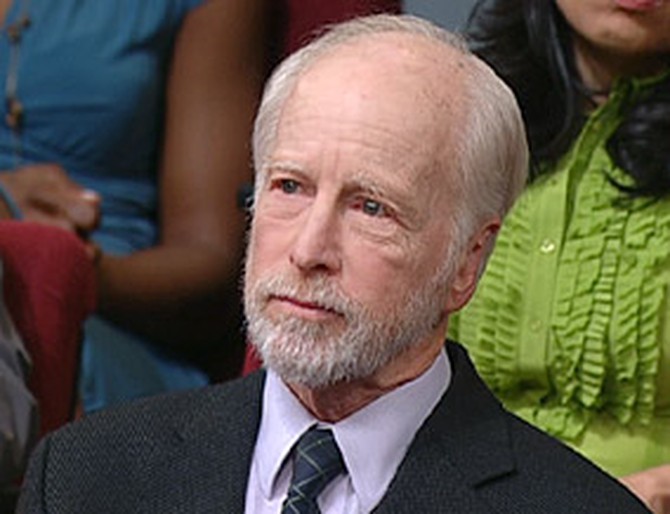

Dr. Tony Greenwald, one of the psychologists who developed the test, says many people initially blame their results on the test, not themselves. The good news, according to Dr. Greenwald, is it is possible to change your test results. "One of the first experiments we did was one in which we showed images of admirable black Americans. People like Martin Luther King Jr., Colin Powell, Michael Jordan and, yes, Oprah Winfrey. Showing those kinds of images before the test increases the association of African-American with goodness," Dr. Greenwald says.

The bad news, Dr. Greenwald says, is that the change generally lasts only as long as the experiment. The way to permanently change a person's biases is to change what they are exposed to on a daily basis, Malcolm says. "If this unconscious side of us is reflecting our experiences, then if we choose different experiences, then that unconscious side of us changes as well," Malcolm says. "If you want to have a positive association between goodness and African-Americans, then you must surround yourself or put yourself in environments where those kinds of experiences and associations happen and are possible."

Take the test at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit.

The bad news, Dr. Greenwald says, is that the change generally lasts only as long as the experiment. The way to permanently change a person's biases is to change what they are exposed to on a daily basis, Malcolm says. "If this unconscious side of us is reflecting our experiences, then if we choose different experiences, then that unconscious side of us changes as well," Malcolm says. "If you want to have a positive association between goodness and African-Americans, then you must surround yourself or put yourself in environments where those kinds of experiences and associations happen and are possible."

Take the test at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit.

Published 01/01/2006