Mothers Battle Autism

If your child stopped speaking, wouldn't look you in the eye and completely ignored the world around them, what would you do? In her new book, Louder Than Words: A Mother's Journey in Healing Autism, actress Jenny McCarthy shares her emotional story of diagnosis, hope, faith and recovery—a journey many thousands of parents now face.

In 2002, Jenny gave birth to a beautiful baby boy she named Evan. As an infant, Evan was full of life, making eye contact and smiling, but soon things started to change. "God was giving me many hints about my son, and I didn't quite see them," she says. "So I know that he had to wake me up with two really big ones."

Jenny says the first of those "big hints" came on a typical morning when Evan was 2 1/2 years old. When Evan, who usually got up at 7 a.m., wasn't stirring by 7:45 a.m. Jenny knew something was wrong. She ran to the nursery. "I open the door and run to his crib and I find him in his crib, convulsing, struggling to breathe, his eyeballs rolled to the back of his head," she says. "I picked him up and I started screaming at the top of my lungs ... the paramedics came, and it took about 20 minutes for the seizure to stop."

When they arrived at the hospital, Jenny says doctors told her that her son had a febrile seizure, caused by a fever. "I said to the doctor, 'Well, you know, he doesn't really have a fever, so how does that play in this scenario?'" Jenny says. "[The doctor said], 'Well, he could have been getting one.' That was the response I got. ... I went home with my baby going, 'You know what? Something's wrong and I don't know what it is, but I feel it."

In 2002, Jenny gave birth to a beautiful baby boy she named Evan. As an infant, Evan was full of life, making eye contact and smiling, but soon things started to change. "God was giving me many hints about my son, and I didn't quite see them," she says. "So I know that he had to wake me up with two really big ones."

Jenny says the first of those "big hints" came on a typical morning when Evan was 2 1/2 years old. When Evan, who usually got up at 7 a.m., wasn't stirring by 7:45 a.m. Jenny knew something was wrong. She ran to the nursery. "I open the door and run to his crib and I find him in his crib, convulsing, struggling to breathe, his eyeballs rolled to the back of his head," she says. "I picked him up and I started screaming at the top of my lungs ... the paramedics came, and it took about 20 minutes for the seizure to stop."

When they arrived at the hospital, Jenny says doctors told her that her son had a febrile seizure, caused by a fever. "I said to the doctor, 'Well, you know, he doesn't really have a fever, so how does that play in this scenario?'" Jenny says. "[The doctor said], 'Well, he could have been getting one.' That was the response I got. ... I went home with my baby going, 'You know what? Something's wrong and I don't know what it is, but I feel it."

About three weeks after the initial seizure, Evan had a second episode. Jenny says she had driven him three hours to see his grandparents when she noticed a "kind of stoned look on his face" as she handed him to his grandmother. "I walk into the bedroom to give Evan his bottle, and he's lying flat on the bed with his eyes rolled in the back of his head," Jenny says. "I called 911 because I knew it was happening again."

Her instinct was to put cold rags on him—a common treatment for febrile seizures. But Jenny says this one was different. "He wasn't convulsing, nor was he trying to get any breath—[there was] just foam coming out of his mouth," she says. "I put my hand on him, and I kept saying, 'Just stay with me,' because I felt like he was going. And after a few moments, I felt his heart stop."

When paramedics arrived they began CPR on Evan. "At that very moment that I watched my baby trying to get his heart started, I remember thinking, 'Why?'" Jenny says. "And then I heard this voice [inside me] that said, 'Everything is going to be okay.' I don't know how in the midst of hell that I was in that this voice [said], 'Everything's going to be okay,' and it's like ... peace came over my body."

The paramedics revived Evan, but with no available helicopter, he had to be driven three hours back to Los Angeles for treatment. "In that time, he had another seizure. By the time we got to the Los Angeles hospital, he had seven more seizures within a seven-hour period," she says. Two days later, a doctor diagnosed Evan with epilepsy. "[The doctor said], 'There's got to be someone with seizures on your side of the family.' I said, 'No, actually I know every branch. I know what's going on. There's nothing. No one [with] epilepsy," she says. "And they discharged us."

Her instinct was to put cold rags on him—a common treatment for febrile seizures. But Jenny says this one was different. "He wasn't convulsing, nor was he trying to get any breath—[there was] just foam coming out of his mouth," she says. "I put my hand on him, and I kept saying, 'Just stay with me,' because I felt like he was going. And after a few moments, I felt his heart stop."

When paramedics arrived they began CPR on Evan. "At that very moment that I watched my baby trying to get his heart started, I remember thinking, 'Why?'" Jenny says. "And then I heard this voice [inside me] that said, 'Everything is going to be okay.' I don't know how in the midst of hell that I was in that this voice [said], 'Everything's going to be okay,' and it's like ... peace came over my body."

The paramedics revived Evan, but with no available helicopter, he had to be driven three hours back to Los Angeles for treatment. "In that time, he had another seizure. By the time we got to the Los Angeles hospital, he had seven more seizures within a seven-hour period," she says. Two days later, a doctor diagnosed Evan with epilepsy. "[The doctor said], 'There's got to be someone with seizures on your side of the family.' I said, 'No, actually I know every branch. I know what's going on. There's nothing. No one [with] epilepsy," she says. "And they discharged us."

Jenny says every instinct she had was telling her that her son was not epileptic—so she went for a second opinion.

After spending 20 minutes with Evan, a neurologist gave Jenny what she describes as a devastating diagnosis—Evan had autism. "And boy, my mommy instinct said, 'This man is right,'" she says.

Jenny says hearing the words made her feel "like death." "[The doctor] said, 'Hey, don't forget. This is the same little boy you came in this room with. He's not any different. He's the same boy,'" she says. "And, true, he was correct. He was the same boy. But I did happen to say, 'Well, I believe my son is trapped inside. I'm not settling for this.'"

In hindsight, Jenny realizes she missed signs of Evan's autism—such as his obsession with moving objects. Others had noticed something different about Evan, too. "My mother-in-law said, 'He doesn't really show affection,' and I threw her out of the house," Jenny says. "I went to a play gym, and the woman [there] said, 'Does your son have a brain problem?' ... [I said], 'How dare you say something about my child? I love him. He's perfect. You can't say that about a child.' I just had no idea."

After spending 20 minutes with Evan, a neurologist gave Jenny what she describes as a devastating diagnosis—Evan had autism. "And boy, my mommy instinct said, 'This man is right,'" she says.

Jenny says hearing the words made her feel "like death." "[The doctor] said, 'Hey, don't forget. This is the same little boy you came in this room with. He's not any different. He's the same boy,'" she says. "And, true, he was correct. He was the same boy. But I did happen to say, 'Well, I believe my son is trapped inside. I'm not settling for this.'"

In hindsight, Jenny realizes she missed signs of Evan's autism—such as his obsession with moving objects. Others had noticed something different about Evan, too. "My mother-in-law said, 'He doesn't really show affection,' and I threw her out of the house," Jenny says. "I went to a play gym, and the woman [there] said, 'Does your son have a brain problem?' ... [I said], 'How dare you say something about my child? I love him. He's perfect. You can't say that about a child.' I just had no idea."

As with most autistic children, Jenny says she noticed that Evan's personality seemed to be locked inside him—and she was determined to get him out. She began scouring the Internet, where she read recovery stories and discovered treatment options.

One treatment Jenny decided to try was a change in eating habits. She immediately started eliminating gluten and casein, found in wheat and dairy products, from Evan's diet. "In two weeks to three weeks—and this isn't for everyone, to get a reaction like this—Evan doubled his language," she says. "[There was] eye contact, smiling, more affection."

To help Evan learn to play with toys as other children do, Jenny tried another approach—video modeling and play therapy. Because Evan didn't know how to play catch, Jenny showed him a video of her catching a ball. From that day on, Jenny says he was into the game. She used play therapy to help him learn in other ways. "A lot of kids on the [autism] spectrum, including Evan, would take [a toy] car and just line them up or turn them upside down and just [spin the wheels]," she says. "So play therapy literally is teaching him that the car can go on an adventure."

With the help of these treatments, Jenny says 5-year-old Evan is making great strides. "I consider him in recovery. There's still things we need to work on—seizures, stuff with abstract understanding, but for the most part he's a typical child in normal school," she says. While these therapies worked for Evan, Jenny emphasizes that it might not work for every child with autism. "I'm just a mom telling a story of other moms. We want to share it and say our kids do get better," she says. "[It's like] chemotherapy. It doesn't work for every cancer victim, but you know what? You're going to give it a try."

One treatment Jenny decided to try was a change in eating habits. She immediately started eliminating gluten and casein, found in wheat and dairy products, from Evan's diet. "In two weeks to three weeks—and this isn't for everyone, to get a reaction like this—Evan doubled his language," she says. "[There was] eye contact, smiling, more affection."

To help Evan learn to play with toys as other children do, Jenny tried another approach—video modeling and play therapy. Because Evan didn't know how to play catch, Jenny showed him a video of her catching a ball. From that day on, Jenny says he was into the game. She used play therapy to help him learn in other ways. "A lot of kids on the [autism] spectrum, including Evan, would take [a toy] car and just line them up or turn them upside down and just [spin the wheels]," she says. "So play therapy literally is teaching him that the car can go on an adventure."

With the help of these treatments, Jenny says 5-year-old Evan is making great strides. "I consider him in recovery. There's still things we need to work on—seizures, stuff with abstract understanding, but for the most part he's a typical child in normal school," she says. While these therapies worked for Evan, Jenny emphasizes that it might not work for every child with autism. "I'm just a mom telling a story of other moms. We want to share it and say our kids do get better," she says. "[It's like] chemotherapy. It doesn't work for every cancer victim, but you know what? You're going to give it a try."

In recent years, the number of children diagnosed with autism has risen from 1 in every 500 children to 1 in 150—and science has not discovered a reason why. Jenny says she believes that childhood vaccinations may play a part. "What number will it take for people just to start listening to what the mothers of children who have seen autism have been saying for years, which is, 'We vaccinated our baby and something happened."

Jenny says even before Evan received his vaccines, she tried to talk to her pediatrician about it. "Right before his MMR shot, I said to the doctor, 'I have a very bad feeling about this shot. This is the autism shot, isn't it?' And he said, 'No, that is ridiculous. It is a mother's desperate attempt to blame something,' and he swore at me, and then the nurse gave [Evan] the shot," she says. "And I remember going, 'Oh, God, I hope he's right.' And soon thereafter—boom—the soul's gone from his eyes."

Despite her belief, Jenny says she is not against vaccines. "I am all for them, but there needs to be a safer vaccine schedule. There needs to be something done. The fact that the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] acts as if these vaccines are one size fits all is just crazy to me," she says. "People need to start listening to what the moms have been saying."

Jenny says even before Evan received his vaccines, she tried to talk to her pediatrician about it. "Right before his MMR shot, I said to the doctor, 'I have a very bad feeling about this shot. This is the autism shot, isn't it?' And he said, 'No, that is ridiculous. It is a mother's desperate attempt to blame something,' and he swore at me, and then the nurse gave [Evan] the shot," she says. "And I remember going, 'Oh, God, I hope he's right.' And soon thereafter—boom—the soul's gone from his eyes."

Despite her belief, Jenny says she is not against vaccines. "I am all for them, but there needs to be a safer vaccine schedule. There needs to be something done. The fact that the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] acts as if these vaccines are one size fits all is just crazy to me," she says. "People need to start listening to what the moms have been saying."

We contacted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about whether there is a link between autism and vaccines and they gave us the following statement:

"CDC places a high priority on vaccine safety and the integrity and credibility of its vaccine safety research. This commitment not only stems from our scientific and medical dedication, it is also personal—for most of us who work at CDC are also parents and grandparents. And as such, we too, have high levels of personal interest and concern in the health and safety of children, families and communities. We simply don't know what causes most cases of autism, but we're doing everything we can to find out. The vast majority of science to date does not support an association between thimerosal in vaccines and autism. But we are currently conducting additional studies to further determine what role, if any, thimerosal in vaccines may play in the development of autism. It is important to remember, vaccines protect and save lives. Vaccines protect infants, children and adults from the unnecessary harm and premature death caused by vaccine-preventable diseases."

"CDC places a high priority on vaccine safety and the integrity and credibility of its vaccine safety research. This commitment not only stems from our scientific and medical dedication, it is also personal—for most of us who work at CDC are also parents and grandparents. And as such, we too, have high levels of personal interest and concern in the health and safety of children, families and communities. We simply don't know what causes most cases of autism, but we're doing everything we can to find out. The vast majority of science to date does not support an association between thimerosal in vaccines and autism. But we are currently conducting additional studies to further determine what role, if any, thimerosal in vaccines may play in the development of autism. It is important to remember, vaccines protect and save lives. Vaccines protect infants, children and adults from the unnecessary harm and premature death caused by vaccine-preventable diseases."

Soon after Evan's diagnosis, Jenny says the stress of raising a child with autism began to take a toll on her marriage. An autism advocacy organization reports that the divorce rate within the autism community is staggering. According to its research, 80 percent of all marriages end.

"I believe it, because I lived it," she says. "I felt very alone in my marriage."

Jenny says her husband dealt with his pain by staying away, even when Evan was in the hospital. "He never sat down and said, 'What did you find out on Google?'" she says. "There was never that connection of wanting to know and being there."

When Jenny's marriage ended, she says she felt sad...and scared. "After the divorce, even though it felt good and the right thing to do, I felt, as I'm sure many mothers with children who have autism feel, 'Who in the heck is going to love me with my child who has autism?'" she says. "I don't care how big your boobs are or blonde your hair is—you're going to feel that way."

Jenny says she began to pray every day that she'd find a man with a big enough heart to love her and Evan. "We come as a pair," she says. "I kept that hope, that vision of a man coming into my life that would love us both equally."

"I believe it, because I lived it," she says. "I felt very alone in my marriage."

Jenny says her husband dealt with his pain by staying away, even when Evan was in the hospital. "He never sat down and said, 'What did you find out on Google?'" she says. "There was never that connection of wanting to know and being there."

When Jenny's marriage ended, she says she felt sad...and scared. "After the divorce, even though it felt good and the right thing to do, I felt, as I'm sure many mothers with children who have autism feel, 'Who in the heck is going to love me with my child who has autism?'" she says. "I don't care how big your boobs are or blonde your hair is—you're going to feel that way."

Jenny says she began to pray every day that she'd find a man with a big enough heart to love her and Evan. "We come as a pair," she says. "I kept that hope, that vision of a man coming into my life that would love us both equally."

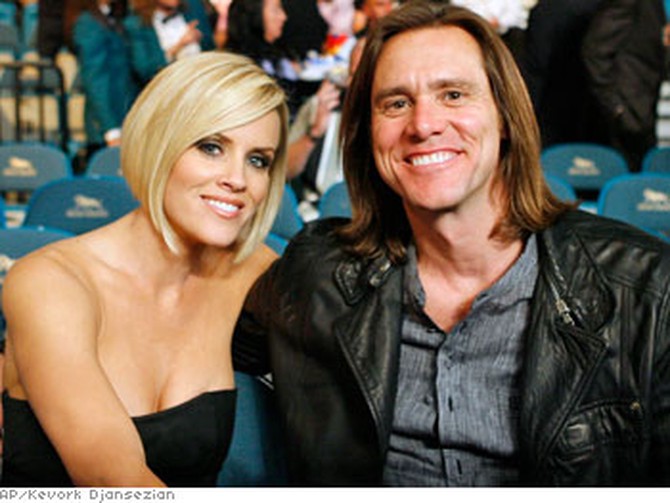

In the midst of the seizures, doctor visits and divorce, Jenny met the man she was looking for, actor Jim Carrey.

The pair hit it off right away, but Jenny says she waited a few months to tell him about Evan's diagnosis. "I did not tell him initially, you know, 'Hi, how are you? I have a child with autism. Do you want to date me?'" she says. "It's something you're personally kind of afraid to share."

In the beginning, Jenny says she was just looking for someone to hold her and notice her pretty new blouse. "I just needed that so badly," she says.

At one point in their relationship, Jenny says she had to say goodbye to Jim because Evan's condition was getting worse. Suddenly, she says her priorities went from kissing Jim on the sofa to focusing solely on her child's health.

When Evan began to recover, Jenny's "girl instincts" took over. She says she sent Jim a text message that said, "Is there still room on your sofa or has the seat been filled?" Jim replied, "Your seat will always be here."

From that day on, Jenny says Jim has been a big part of her and Evan's life. "He has been so wonderful in Evan's life," she says. "Let me tell you, ladies, Jim Carrey knows a lot about autism. He has been through it all with me. ... He did fall in love with Evan, and he's so good with him. [He's] opened his heart and the relationship is great."

The pair hit it off right away, but Jenny says she waited a few months to tell him about Evan's diagnosis. "I did not tell him initially, you know, 'Hi, how are you? I have a child with autism. Do you want to date me?'" she says. "It's something you're personally kind of afraid to share."

In the beginning, Jenny says she was just looking for someone to hold her and notice her pretty new blouse. "I just needed that so badly," she says.

At one point in their relationship, Jenny says she had to say goodbye to Jim because Evan's condition was getting worse. Suddenly, she says her priorities went from kissing Jim on the sofa to focusing solely on her child's health.

When Evan began to recover, Jenny's "girl instincts" took over. She says she sent Jim a text message that said, "Is there still room on your sofa or has the seat been filled?" Jim replied, "Your seat will always be here."

From that day on, Jenny says Jim has been a big part of her and Evan's life. "He has been so wonderful in Evan's life," she says. "Let me tell you, ladies, Jim Carrey knows a lot about autism. He has been through it all with me. ... He did fall in love with Evan, and he's so good with him. [He's] opened his heart and the relationship is great."

Mothers of children with autism provide invaluable support to one another...even in Hollywood. When Jenny was first researching autism, she reached out to a celebrity whose son is struggling with the same disease—Holly Robinson Peete. Jenny calls Holly her "angel."

In their first phone conversation, Holly says they talked for about nine hours. "[Holly] gave me that hope that no doctor did," Jenny says.

Holly and her husband, retired NFL quarterback Rodney Peete, received their son R.J.'s diagnosis in 1999 but waited until the summer of 2007 to go public with their experiences. Holly says they waited to talk about autism until they felt more informed. "I didn't feel like I knew enough about the disorder at that point," she says.

Back in 1999, Holly says there were very few resources for parents of autistic children. Even doctors were less informed than they are today. "I had a developmental pediatrician tell me, 'Your son will never do this, he will never say he loves you, he will never do that,'" she says. "It was a very interesting ride."

Previously, 1 in 500 children was diagnosed with this neurological disorder. Today, Holly says 1 in every 94 boys is affected. For unknown reasons, autism disproportionately affects boys.

In their first phone conversation, Holly says they talked for about nine hours. "[Holly] gave me that hope that no doctor did," Jenny says.

Holly and her husband, retired NFL quarterback Rodney Peete, received their son R.J.'s diagnosis in 1999 but waited until the summer of 2007 to go public with their experiences. Holly says they waited to talk about autism until they felt more informed. "I didn't feel like I knew enough about the disorder at that point," she says.

Back in 1999, Holly says there were very few resources for parents of autistic children. Even doctors were less informed than they are today. "I had a developmental pediatrician tell me, 'Your son will never do this, he will never say he loves you, he will never do that,'" she says. "It was a very interesting ride."

Previously, 1 in 500 children was diagnosed with this neurological disorder. Today, Holly says 1 in every 94 boys is affected. For unknown reasons, autism disproportionately affects boys.

Over the years, Holly says she's realized autism is like a wall around your child. "You have to be like a superhero [or] Foxy Brown and kick that wall down and make cracks in that wall to bring your child through," she says. "You have a very short window of time, and you have to get busy. ... The more cracks you make, the more you have an opportunity to bring them into our world."

Like Jenny, Holly has tried to reverse the effects of her son's autism with dietary programs and behavior therapies. When Holly got R.J. tested and found out he was allergic to gluten, she put him on a wheat-free diet. "[Gluten] makes him crazy," she says. "And he can't focus. So we took the wheat out, and that made a huge difference."

Holly says she and Rodney have also tried every type of therapy—from speech therapy to floor time to applied behavioral analysis. "He's responded to some things well and others not so well," she says. "We've tried to focus [on the most successful] and pick and choose."

They have also tried to focus on maintaining a healthy, happy relationship. Holly says autism impacted her marriage, but she and Rodney learned to rely on each other when times were tough. "I just am so lucky to have him. I know how hard it is for the men and their boys," she says. "We women, you know, we fight and we do what we have to do. ... I'm just glad he stuck around to be my partner in this thing, because I couldn't have done it without him."

Like Jenny, Holly has tried to reverse the effects of her son's autism with dietary programs and behavior therapies. When Holly got R.J. tested and found out he was allergic to gluten, she put him on a wheat-free diet. "[Gluten] makes him crazy," she says. "And he can't focus. So we took the wheat out, and that made a huge difference."

Holly says she and Rodney have also tried every type of therapy—from speech therapy to floor time to applied behavioral analysis. "He's responded to some things well and others not so well," she says. "We've tried to focus [on the most successful] and pick and choose."

They have also tried to focus on maintaining a healthy, happy relationship. Holly says autism impacted her marriage, but she and Rodney learned to rely on each other when times were tough. "I just am so lucky to have him. I know how hard it is for the men and their boys," she says. "We women, you know, we fight and we do what we have to do. ... I'm just glad he stuck around to be my partner in this thing, because I couldn't have done it without him."

R.J., who turns 10 years old in October 2007, has made a lot of progress

over the years thanks to Holly and Rodney's persistence and patience. He has

even learned to play the piano. "He has perfect pitch," Holly says.

Rodney opens up about his son's diagnosis.

Although some family members were critical of Holly and Rodney's decision to go public with their son's disorder, Holly is happy with the outcome. "My son is amazing. He's come a long way, and he is very conscious of the fact that he's helping other people by the family sharing his story," she says.

By talking openly about autism, Holly hopes people will begin to change their perception of the children who live with it every day. "We need to value these children that are here. We need to stop thinking about them as children who are retarded," she says. "We need to stop thinking about them as children who don't have the capacity to learn."

Holly says R.J. was kicked out of one school because the educators deemed him "unteachable." Now, he's working with a partner in a new school and making strides. "We have to figure out how their brains work," Holly says. "There are a lot of people who are on the spectrum who are brilliant."

Rodney opens up about his son's diagnosis.

Although some family members were critical of Holly and Rodney's decision to go public with their son's disorder, Holly is happy with the outcome. "My son is amazing. He's come a long way, and he is very conscious of the fact that he's helping other people by the family sharing his story," she says.

By talking openly about autism, Holly hopes people will begin to change their perception of the children who live with it every day. "We need to value these children that are here. We need to stop thinking about them as children who are retarded," she says. "We need to stop thinking about them as children who don't have the capacity to learn."

Holly says R.J. was kicked out of one school because the educators deemed him "unteachable." Now, he's working with a partner in a new school and making strides. "We have to figure out how their brains work," Holly says. "There are a lot of people who are on the spectrum who are brilliant."

Many parents of children with autism may not have the same success as Jenny and Holly, but these Hollywood moms want them to come away with one thing—hope. "I want to say [to parents], you're not alone. There's a lot of hope," Holly says. "It's a new day in the world of autism, and we're fighting."

Holly says the CDC's statement about vaccinations has given her hope that parents and medical professionals can lay down their arms and open the lines of communication. "I would just say to the pediatricians, listen to [mothers] sometimes and give us a little bit more respect," Holly says. "Our gut is really dead on."

Jenny urges moms in her situation not to feel guilty about their child's diagnosis and to trust their instincts.

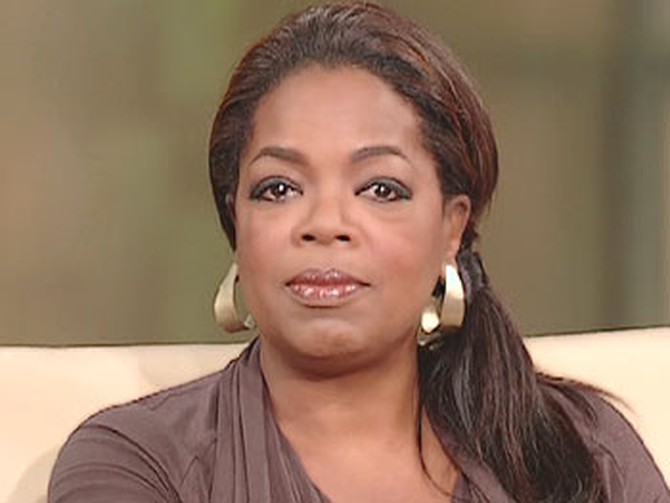

"You're mother warriors is what you are," Oprah says.

Find out more about the disease and meet others living with autism.

Holly says the CDC's statement about vaccinations has given her hope that parents and medical professionals can lay down their arms and open the lines of communication. "I would just say to the pediatricians, listen to [mothers] sometimes and give us a little bit more respect," Holly says. "Our gut is really dead on."

Jenny urges moms in her situation not to feel guilty about their child's diagnosis and to trust their instincts.

"You're mother warriors is what you are," Oprah says.

Find out more about the disease and meet others living with autism.

Published 09/18/2007