Living with Neurofibromatosis

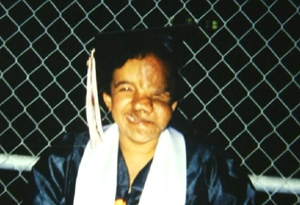

For 29-year-old Ana Rodarte, going out in public was once considered torture. "There has been several times when little kids see me and they'd just start crying," she says. "It's very hard emotionally to have the life I've lived. Growing up, I built up a wall. I didn't want people to see how hurt I was, because it would make me vulnerable."

Ana lives with an incurable, disfiguring disease called neurofibromatosis (NF). The genetic disease affects 1 in 3,000 people and causes tumors to grow along nerves. The tumors can grow anywhere on or in the body. The disease is sometimes referred to as elephant man's disease, but this term is highly offensive to those in the NF community.

For the first time, Ana is telling her story to help people understand what it's like to live with NF.

Ana lives with an incurable, disfiguring disease called neurofibromatosis (NF). The genetic disease affects 1 in 3,000 people and causes tumors to grow along nerves. The tumors can grow anywhere on or in the body. The disease is sometimes referred to as elephant man's disease, but this term is highly offensive to those in the NF community.

For the first time, Ana is telling her story to help people understand what it's like to live with NF.

When Ana was a few months old, her parents noticed a small, red mark on her face. "It looked like a bee sting," she says.

As Ana got older, the mark grew bigger. "Around the time I started playing with crayons, I started realizing that I was different from the other kids," she says. "They would ask me why I looked the way I did, and I didn't have a way to explain it because I didn't know myself."

Though her classmates were able to see past Ana's appearance, Ana says she grew up wanting to be like her friends. "I asked why God was so mean, and my parents would say it was just the way he wanted me to be born," she says. "I felt like I did something wrong."

As Ana got older, the mark grew bigger. "Around the time I started playing with crayons, I started realizing that I was different from the other kids," she says. "They would ask me why I looked the way I did, and I didn't have a way to explain it because I didn't know myself."

Though her classmates were able to see past Ana's appearance, Ana says she grew up wanting to be like her friends. "I asked why God was so mean, and my parents would say it was just the way he wanted me to be born," she says. "I felt like I did something wrong."

Ana's parents moved from Mexico to the United States to get better care for their daughter. Throughout her childhood, Ana had multiple surgeries to remove the tumor in her face. "After every surgery, the tumor would grow back," she says. "It really broke my heart, even until I just lost faith in the doctors and didn't want to continue the process."

At 14, Ana noticed her tumors were growing more rapidly. "To some extent, I didn't want to go to school because I was just real insecure about how people would treat me," she says.

After graduation, Ana enrolled in a local college but didn't complete her coursework. "They offered me disabled services," she says. "I got offended because I didn't think I needed it."

With many of her longtime friends away at school, Ana says she began to feel alone and depressed. "For the next two to three years, I just pretty much secluded myself from people," she says. "I did try to get a job, but I thought I was discriminated because of how I looked. I would leave my house maybe once a month."

At 14, Ana noticed her tumors were growing more rapidly. "To some extent, I didn't want to go to school because I was just real insecure about how people would treat me," she says.

After graduation, Ana enrolled in a local college but didn't complete her coursework. "They offered me disabled services," she says. "I got offended because I didn't think I needed it."

With many of her longtime friends away at school, Ana says she began to feel alone and depressed. "For the next two to three years, I just pretty much secluded myself from people," she says. "I did try to get a job, but I thought I was discriminated because of how I looked. I would leave my house maybe once a month."

By the time Ana turned 22, the tumor on her face had grown so large it covered her left eye. "I struggled a lot with reading. I had to deal with a lot of headaches," she says. "It became really hard to eat. When I would chew on the left side of my face, it would result in me biting into it."

At 24, Ana met a surgeon who gave her new hope—Dr. Munish Batra. "When I looked at her for the first time, I was completely just amazed that she hadn't had [more] help up until this time," he says. "As surgeons, we know that there's a lot we can do for this."

With Ana's consent, Dr. Batra and a team of surgeons at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, California, began a series of risky—and ultimately successful—surgeries to remove the 2-pound tumor from her face. "There's a chance that they may progress [in the future]," he says. "But at this stage, it seems less likely because she's been at a fairly stable growth phase."

At 24, Ana met a surgeon who gave her new hope—Dr. Munish Batra. "When I looked at her for the first time, I was completely just amazed that she hadn't had [more] help up until this time," he says. "As surgeons, we know that there's a lot we can do for this."

With Ana's consent, Dr. Batra and a team of surgeons at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, California, began a series of risky—and ultimately successful—surgeries to remove the 2-pound tumor from her face. "There's a chance that they may progress [in the future]," he says. "But at this stage, it seems less likely because she's been at a fairly stable growth phase."

Before surgery, Ana says relatives used to force her to leave the house. "I thank them now because I don't know what I would have done if I would have been secluded," she says.

Now, Ana says she's happy to go out on her own. "Being in public now is completely different," she says. "I'm more friendly to people. I don't see them as a threat like I did before. I learned it was better for me to let people in and not hide my feelings."

Go inside Ana's life today

Ana says she's also much more comfortable with herself. "It took a lot of years to accept myself, but I am who I am," she says. "I feel a lot more confident now when I look in the mirror. A bit more resemblance of a normal person. I'm being more social and just wanting more things in life."

The only thing Ana says she's not willing to do is have children. "I don't want to pass on the disease," she says. "But it hasn't prevented me from dating."

Ana says she hopes her story can help others in her situation live fulfilling lives. "I want to let people know there's help and let parents know not to shelter their kids or people that are older not shelter themselves from society," she says. "That's not the way to live."

Now, Ana says she's happy to go out on her own. "Being in public now is completely different," she says. "I'm more friendly to people. I don't see them as a threat like I did before. I learned it was better for me to let people in and not hide my feelings."

Go inside Ana's life today

Ana says she's also much more comfortable with herself. "It took a lot of years to accept myself, but I am who I am," she says. "I feel a lot more confident now when I look in the mirror. A bit more resemblance of a normal person. I'm being more social and just wanting more things in life."

The only thing Ana says she's not willing to do is have children. "I don't want to pass on the disease," she says. "But it hasn't prevented me from dating."

Ana says she hopes her story can help others in her situation live fulfilling lives. "I want to let people know there's help and let parents know not to shelter their kids or people that are older not shelter themselves from society," she says. "That's not the way to live."