Leaders of the Freedom Rider Movement

Photo: Getty Images

More than 400 Americans risked their lives during the 1961 Freedom Rides, but behind the scenes, a few visionary leaders offered guidance, protection and prayer. Find out more about these unsung heroes.

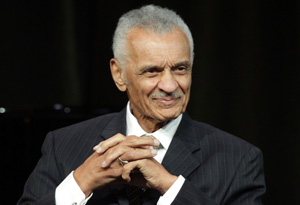

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy The Rev. Ralph Abernathy was a key figure in the civil rights movement of the '60s and beyond. As the young pastor of First Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, he and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were among the leaders of the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott organized in response to the arrest of Rosa Parks.

In 1961, the Rev. Abernathy's First Baptist Church was the site of the May 21 "siege" where an angry mob of white segregationists surrounded 1,500 people inside the sanctuary. At one point, the situation seemed so dire that the Rev. Abernathy and Dr. King considered giving themselves up to the mob to save the men, women and children in the sanctuary.

When reporters asked the Rev. Abernathy to respond to Robert Kennedy's complaint that the Freedom Riders were embarrassing the United States in front of the world, Abernathy responded, "Well, doesn't the attorney general know we've been embarrassed all our lives?"

On May 25, 1961, the Rev. Abernathy was arrested on breach of peace charges after escorting William Sloane Coffin's Connecticut Freedom Ride to the Montgomery Greyhound bus terminal, neither the first nor the last instance of civil disobedience in a lifetime of activism.

After Dr. King's assassination on April 4, 1968, Abernathy took up the leadership of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) Poor People's Campaign and led the 1968 March on Washington. The Rev. Abernathy died in 1990.

More Movement Leaders

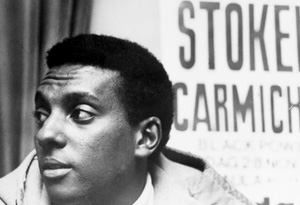

Stokely Carmichael

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Diane Nash

Fred Shuttlesworth

C.T. Vivian

James Lawson

Photo: Getty Images

Stokely Carmichael

At the time of the Freedom Rides, Stokely Carmichael was a 19-year-old student at Howard University and the son of West Indian immigrants to New York City. Stokely made the journey to Jackson, Mississippi, from New Orleans, Louisiana, on June 4, 1961, by train, along with eight other riders, including Joan Trumpauer.

The group was ushered by Jackson police to a waiting paddy wagon; all Riders refused bail. Stokely was transferred to Parchman State Prison Farm, which proved to be a crucible and testing ground for future movement leaders. Other Freedom Riders recalled his quick wit and hard-nosed political realism from their shared time at Parchman.

The acerbic Stokely would go on to become one of the leading voices of the black power movement. In 1966, Stokely became Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman and, in 1967, honorary prime minister of the Black Panther Party. He moved to West Africa in 1969, and changed his name to Kwame Ture in honor of African leaders Kwame Nkruma and Sekou Toure, later traveling the world as a proponent of the All African Peoples Revolutionary Party. He died in Conakry, Guinea, in 1998 of prostate cancer at the age of 57.

In his posthumously published autobiography, Stokely spoke about the significance of the Freedom Rides: "CORE would be sending an integrated team—black and white together—from the nation's capital to New Orleans on public transportation. That's all. Except, of course, that they would sit randomly on the buses in integrated pairs and in the stations they would use waiting room facilities casually, ignoring the white/colored signs. What could be more harmless...in any even marginally healthy society?"

At the time of the Freedom Rides, Stokely Carmichael was a 19-year-old student at Howard University and the son of West Indian immigrants to New York City. Stokely made the journey to Jackson, Mississippi, from New Orleans, Louisiana, on June 4, 1961, by train, along with eight other riders, including Joan Trumpauer.

The group was ushered by Jackson police to a waiting paddy wagon; all Riders refused bail. Stokely was transferred to Parchman State Prison Farm, which proved to be a crucible and testing ground for future movement leaders. Other Freedom Riders recalled his quick wit and hard-nosed political realism from their shared time at Parchman.

The acerbic Stokely would go on to become one of the leading voices of the black power movement. In 1966, Stokely became Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman and, in 1967, honorary prime minister of the Black Panther Party. He moved to West Africa in 1969, and changed his name to Kwame Ture in honor of African leaders Kwame Nkruma and Sekou Toure, later traveling the world as a proponent of the All African Peoples Revolutionary Party. He died in Conakry, Guinea, in 1998 of prostate cancer at the age of 57.

In his posthumously published autobiography, Stokely spoke about the significance of the Freedom Rides: "CORE would be sending an integrated team—black and white together—from the nation's capital to New Orleans on public transportation. That's all. Except, of course, that they would sit randomly on the buses in integrated pairs and in the stations they would use waiting room facilities casually, ignoring the white/colored signs. What could be more harmless...in any even marginally healthy society?"

Photo: Getty Images

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The best known leader of the civil rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, the son of prominent pastor Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. Dr. King became pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was 25 years old. He received national attention for his role in the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott to end segregated city buses. He helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957 and served as its first president.

Dr. King's support for CORE's Freedom Ride campaign was initially limited and cautious. At a reception held for the Freedom Riders in Atlanta, he passed on warnings of planned Klan violence ahead, telling the Riders, "You will never make it through Alabama."

Later, after the Freedom Riders had made their way to Montgomery, Alabama, he spoke eloquently on behalf of their campaign to the national media and from the pulpit at First Baptist Church, just prior to its siege and firebombing. Dr. King was an active participant in strategy sessions over the next three days, as the Riders holed up in the Montgomery mansion of Dr. Richard Harris. However, Dr. King declined to become a Freedom Rider himself, disappointing several of the younger Riders, who mockingly referred to him as "De Lawd."

Later in the decade, Dr. King worked with many of the new leaders who emerged from the Freedom Rides on campaigns such as the March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery marches to achieve important movement victories, culminating in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Dr. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Prior to his assassination in 1968, Dr. King had shifted his efforts on the Poor Peoples Campaign to combat economic injustice and opposition to the Vietnam War. In 1986, Dr. King's birthday became a national holiday.

The best known leader of the civil rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, the son of prominent pastor Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. Dr. King became pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was 25 years old. He received national attention for his role in the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott to end segregated city buses. He helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957 and served as its first president.

Dr. King's support for CORE's Freedom Ride campaign was initially limited and cautious. At a reception held for the Freedom Riders in Atlanta, he passed on warnings of planned Klan violence ahead, telling the Riders, "You will never make it through Alabama."

Later, after the Freedom Riders had made their way to Montgomery, Alabama, he spoke eloquently on behalf of their campaign to the national media and from the pulpit at First Baptist Church, just prior to its siege and firebombing. Dr. King was an active participant in strategy sessions over the next three days, as the Riders holed up in the Montgomery mansion of Dr. Richard Harris. However, Dr. King declined to become a Freedom Rider himself, disappointing several of the younger Riders, who mockingly referred to him as "De Lawd."

Later in the decade, Dr. King worked with many of the new leaders who emerged from the Freedom Rides on campaigns such as the March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery marches to achieve important movement victories, culminating in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Dr. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Prior to his assassination in 1968, Dr. King had shifted his efforts on the Poor Peoples Campaign to combat economic injustice and opposition to the Vietnam War. In 1986, Dr. King's birthday became a national holiday.

Photo: George Burns/Harpo Studios

Diane Nash

By 1961, Diane Nash had emerged as one of the most respected student leaders of the sit-in movement in Nashville, Tennessee. Raised in a middle-class Catholic family in Chicago, Diane attended Howard University before transferring to Nashville's Fisk University in the fall of 1959. Shocked by the extent of segregation she encountered in Tennessee, she was a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in April 1960. In February 1961, she served jail time in solidarity with the "Rock Hill Nine"—nine students imprisoned after a lunch counter sit-in.

When the students learned of the bus burning in Anniston, Alabama, and the riot in Birmingham, Alabama, Diane argued that it was their duty to continue.

"It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence," Diane says in Freedom Riders. Elected coordinator of the Nashville Student Movement Ride, Diane monitored the progress of the Ride from Nashville, Tennessee, recruiting new Riders, speaking to the press and working to gain the support of national movement leaders and the federal government.

Assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy John Seigenthaler recalls a phone conversation with Diane when he tried to dissuade the Nashville Freedom Riders from going to Alabama, warning of the violence ahead. Diane replied that the Riders had signed their last wills and testaments prior to departure.

In his interview for Freedom Riders, Seigenthaler recalls, "She, in a very quiet but strong way, gave me a lecture." Diane played a key role in bringing the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to Montgomery on May 21 in support of the Riders. She herself was present for the violent siege of First Baptist Church.

Later that same year, she married Freedom Rider James Bevel. In 1962, she was sentenced to two years in prison for teaching nonviolent tactics to children in Jackson, Mississippi, although she was four months pregnant. She was later released on appeal. Nash played a major role in the Birmingham desegregation campaign of 1963 and the Selma voting-rights campaign of 1965, before returning to her native Chicago to work in education, real estate and fair-housing advocacy. She received an honorary degree from Fisk University in 2009.

By 1961, Diane Nash had emerged as one of the most respected student leaders of the sit-in movement in Nashville, Tennessee. Raised in a middle-class Catholic family in Chicago, Diane attended Howard University before transferring to Nashville's Fisk University in the fall of 1959. Shocked by the extent of segregation she encountered in Tennessee, she was a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in April 1960. In February 1961, she served jail time in solidarity with the "Rock Hill Nine"—nine students imprisoned after a lunch counter sit-in.

When the students learned of the bus burning in Anniston, Alabama, and the riot in Birmingham, Alabama, Diane argued that it was their duty to continue.

"It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Ride to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted, the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence," Diane says in Freedom Riders. Elected coordinator of the Nashville Student Movement Ride, Diane monitored the progress of the Ride from Nashville, Tennessee, recruiting new Riders, speaking to the press and working to gain the support of national movement leaders and the federal government.

Assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy John Seigenthaler recalls a phone conversation with Diane when he tried to dissuade the Nashville Freedom Riders from going to Alabama, warning of the violence ahead. Diane replied that the Riders had signed their last wills and testaments prior to departure.

In his interview for Freedom Riders, Seigenthaler recalls, "She, in a very quiet but strong way, gave me a lecture." Diane played a key role in bringing the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to Montgomery on May 21 in support of the Riders. She herself was present for the violent siege of First Baptist Church.

Later that same year, she married Freedom Rider James Bevel. In 1962, she was sentenced to two years in prison for teaching nonviolent tactics to children in Jackson, Mississippi, although she was four months pregnant. She was later released on appeal. Nash played a major role in the Birmingham desegregation campaign of 1963 and the Selma voting-rights campaign of 1965, before returning to her native Chicago to work in education, real estate and fair-housing advocacy. She received an honorary degree from Fisk University in 2009.

Photo: AP

The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth

The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth was Birmingham's leading civil rights activist at the time of the Freedom Rides. A co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he welcomed the Freedom Riders who showed up on his doorstep on May 14, 1961, bleeding and battered after the riot at the Trailways bus terminal and the Anniston bombing.

He offered the group shelter at the parsonage while seeking medical care for the badly injured Charles Person and Jim Peck.

That evening, the Rev. Shuttlesworth spoke at a mass meeting at Bethel Baptist Church. "This is the greatest thing that has ever happened to Alabama, and it has been good for the nation," he insisted. "No matter how many times they beat us up, segregation has still got to go."

The Rev. Shuttlesworth planned to join the Freedom Riders on their May 20 ride to Montgomery but was arrested at the Birmingham Greyhound bus terminal on the charge of refusing to obey a police officer. He later traveled to Montgomery along with other movement leaders to support the Riders and was present during the siege and firebombing of First Baptist Church. The Rev. Shuttlesworth was arrested while escorting William Sloane Coffin and other members of the Connecticut Freedom Ride to the Montgomery Greyhound bus terminal.

In 1961, the Rev. Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati to be pastor of Revelation Baptist Church. However, he remained active in the Deep South civil rights struggle, including the Birmingham desegregation campaign of 1963.

He returned to Birmingham after his retirement in 2007. In 2008, Birmingham's airport officially changed its name to Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport.

The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth was Birmingham's leading civil rights activist at the time of the Freedom Rides. A co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he welcomed the Freedom Riders who showed up on his doorstep on May 14, 1961, bleeding and battered after the riot at the Trailways bus terminal and the Anniston bombing.

He offered the group shelter at the parsonage while seeking medical care for the badly injured Charles Person and Jim Peck.

That evening, the Rev. Shuttlesworth spoke at a mass meeting at Bethel Baptist Church. "This is the greatest thing that has ever happened to Alabama, and it has been good for the nation," he insisted. "No matter how many times they beat us up, segregation has still got to go."

The Rev. Shuttlesworth planned to join the Freedom Riders on their May 20 ride to Montgomery but was arrested at the Birmingham Greyhound bus terminal on the charge of refusing to obey a police officer. He later traveled to Montgomery along with other movement leaders to support the Riders and was present during the siege and firebombing of First Baptist Church. The Rev. Shuttlesworth was arrested while escorting William Sloane Coffin and other members of the Connecticut Freedom Ride to the Montgomery Greyhound bus terminal.

In 1961, the Rev. Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati to be pastor of Revelation Baptist Church. However, he remained active in the Deep South civil rights struggle, including the Birmingham desegregation campaign of 1963.

He returned to Birmingham after his retirement in 2007. In 2008, Birmingham's airport officially changed its name to Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport.

Photo: Getty Images

The Rev. C.T. Vivian

A 36-year-old Baptist minister from Howard, Missouri, the Rev. Cordy "C.T." Vivian was the oldest of the Nashville Riders. A close friend of James Lawson, he had gained the trust of the students involved in the Nashville movement by participating in the 1960 Nashville sit-in campaign to end lunch counter desegregation. On May 24, 1961, he was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, on the formal charge of breach of peace and imprisoned at Parchman State Prison Farm.

One of the civil rights movement's most respected and revered figures, he was named director of Southern Christian Leadership Conference affiliates in 1963, and later founded and led several civil rights organizations, including Vision, the National Anti-Klan Network, the Center of Democratic Renewal and Black Action Strategies and Information Center.

A 36-year-old Baptist minister from Howard, Missouri, the Rev. Cordy "C.T." Vivian was the oldest of the Nashville Riders. A close friend of James Lawson, he had gained the trust of the students involved in the Nashville movement by participating in the 1960 Nashville sit-in campaign to end lunch counter desegregation. On May 24, 1961, he was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, on the formal charge of breach of peace and imprisoned at Parchman State Prison Farm.

One of the civil rights movement's most respected and revered figures, he was named director of Southern Christian Leadership Conference affiliates in 1963, and later founded and led several civil rights organizations, including Vision, the National Anti-Klan Network, the Center of Democratic Renewal and Black Action Strategies and Information Center.

Photo: Getty Images

James Lawson

Thirty-two-year-old Rev. James Lawson introduced the principles of Gandhian nonviolence to many future leaders of the 1960s civil rights movement. Born in western Pennsylvania and raised in Ohio, he spent a year in prison as a conscientious objector during the Korean War, as well as three years as a Methodist missionary in India, where he was deeply influenced by the philosophy and techniques of nonviolent resistance developed by Mohandas Gandhi and his followers.

While enrolled as a divinity student at Oberlin College, James met the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who urged James to postpone his studies and take an active role in the civil rights movement. "We don't have anyone like you," Dr. King told him.

Following Dr. King's advice, James headed south as a field secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In Nashville, Tennessee, he helped organize the Nashville Student Movement's successful sit-in campaign of 1960 and was expelled from Vanderbilt University School of Divinity as a result. He trained Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis and many others through his famous workshops on the tactics of nonviolent direct action.

When the original CORE Freedom Ride stalled in Birmingham, Alabama, James urged the Nashville Student Movement to continue the Freedom Rides. He conducted workshops on nonviolent resistance while the Freedom Riders spent several days holed up in the Montgomery, Alabama, home of Dr. Richard Harris. During an impromptu press conference on the National Guard-escorted bus that traveled from Montgomery to Jackson, Mississippi, he told reporters that the Freedom Riders "would rather risk violence and be able to travel like ordinary passengers" than rely on armed guards who did not understand their philosophy of combating "violence and hate" by "absorbing it without returning it in kind."

In 1968, James chaired the strike committee for sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. At James' request, Dr. King spoke to the striking workers on the day before his assassination. In 1974, James moved to Los Angeles to lead Holman United Methodist Church where he served as pastor for 25 years before retiring in 1999. Throughout his career and into retirement, he has remained active in various human rights advocacy campaigns, including immigrant rights and opposition to war and militarism. In recent years, he has been a distinguished visiting professor at Vanderbilt University.

More from the show

Retrace the Freedom Riders' journey

Explore America's civil rights issues

Freedom Riders: Then and now

Thirty-two-year-old Rev. James Lawson introduced the principles of Gandhian nonviolence to many future leaders of the 1960s civil rights movement. Born in western Pennsylvania and raised in Ohio, he spent a year in prison as a conscientious objector during the Korean War, as well as three years as a Methodist missionary in India, where he was deeply influenced by the philosophy and techniques of nonviolent resistance developed by Mohandas Gandhi and his followers.

While enrolled as a divinity student at Oberlin College, James met the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who urged James to postpone his studies and take an active role in the civil rights movement. "We don't have anyone like you," Dr. King told him.

Following Dr. King's advice, James headed south as a field secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. In Nashville, Tennessee, he helped organize the Nashville Student Movement's successful sit-in campaign of 1960 and was expelled from Vanderbilt University School of Divinity as a result. He trained Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis and many others through his famous workshops on the tactics of nonviolent direct action.

When the original CORE Freedom Ride stalled in Birmingham, Alabama, James urged the Nashville Student Movement to continue the Freedom Rides. He conducted workshops on nonviolent resistance while the Freedom Riders spent several days holed up in the Montgomery, Alabama, home of Dr. Richard Harris. During an impromptu press conference on the National Guard-escorted bus that traveled from Montgomery to Jackson, Mississippi, he told reporters that the Freedom Riders "would rather risk violence and be able to travel like ordinary passengers" than rely on armed guards who did not understand their philosophy of combating "violence and hate" by "absorbing it without returning it in kind."

In 1968, James chaired the strike committee for sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. At James' request, Dr. King spoke to the striking workers on the day before his assassination. In 1974, James moved to Los Angeles to lead Holman United Methodist Church where he served as pastor for 25 years before retiring in 1999. Throughout his career and into retirement, he has remained active in various human rights advocacy campaigns, including immigrant rights and opposition to war and militarism. In recent years, he has been a distinguished visiting professor at Vanderbilt University.

More from the show

Retrace the Freedom Riders' journey

Explore America's civil rights issues

Freedom Riders: Then and now

ONLINE CONTENT COURTESY OF "FREEDOM RIDERS" AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, A WGBH PRODUCTION FOR PBS