Issues Facing America: The '60s

Photo: Library of Congress

The Freedom Rides were influenced by many issues facing America during the 1960s. Find out what was happening in the Deep South and around the country that made this civil rights revolution possible...and necessary.

Jim Crow LawsThe segregation and disenfranchisement laws known as "Jim Crow" affected almost every aspect of daily life, mandating segregation of schools, parks, libraries, drinking fountains, restrooms, buses, trains and restaurants. "Whites Only" and "Colored" signs were constant reminders of the enforced racial order.

In legal theory, blacks received "separate but equal" treatment under the law—in actuality, public facilities for blacks were nearly always inferior to those for whites, when they existed at all. In addition, blacks were systematically denied the right to vote in most of the rural South through the selective application of literacy tests and other racially motivated criteria.

The Jim Crow system was upheld by local government officials and reinforced by acts of terror perpetrated by vigilantes. In 1896, the Supreme Court established the doctrine of separate but equal in Plessy v. Ferguson, after a black man in New Orleans attempted to sit in a whites-only railway car.

Transit was a core component of segregation in the South. Keeping whites and blacks from sitting together on a bus, train or trolley car might seem insignificant, but it was one more link in a system of segregation that had to be defended at all times—lest it collapse. Thus transit was a logical point of attack for the foes of segregation, in the courtroom and on the buses themselves.

It would take several decades of legal action and months of nonviolent direct action before these efforts achieved their intended result.

Photo: Getty Images

Slow Progress

During the first half of the 20th century, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other organizations employed a variety of courtroom strategies to chip away at state and municipal Jim Crow laws mandating racial segregation. These legal maneuvers achieved important victories, such as Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946), in which the Supreme Court struck down segregated seating on interstate buses as a violation of the interstate commerce clause.

With state governments bent on preserving a white supremacist system and a federal government eager to hold onto white southern votes, these legal victories did little to change the immediate reality of daily life for African-Americans in the segregated South. However, over time these legal challenges provided the framework for overturning the apparatus of segregation. Legal victories also gave nonviolent activists greater moral authority in their confrontations with segregationists. In campaigns such as the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation and the 1961 Freedom Rides, activists could proclaim that they were simply exercising their constitutional rights, even as local authorities carted them off to jail.

The finding of Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the U.S. Supreme Court established the "separate but equal" doctrine, was not fully overturned for 58 years—until 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education declared the segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Token school desegregation occurred in Little Rock, Arkansas, and other parts of the South, but the pace of change was slow. Many Jim Crow laws remained on the books and were vigorously enforced well into the 1960s. The system would not be officially dismantled until after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 overturned state Jim Crow laws. This far-reaching federal legislation was prompted by the actions of the Freedom Riders and other direct-action campaigns in the civil rights movement, but it could not have happened without the series of victories won in the courts during earlier decades.

During the first half of the 20th century, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other organizations employed a variety of courtroom strategies to chip away at state and municipal Jim Crow laws mandating racial segregation. These legal maneuvers achieved important victories, such as Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946), in which the Supreme Court struck down segregated seating on interstate buses as a violation of the interstate commerce clause.

With state governments bent on preserving a white supremacist system and a federal government eager to hold onto white southern votes, these legal victories did little to change the immediate reality of daily life for African-Americans in the segregated South. However, over time these legal challenges provided the framework for overturning the apparatus of segregation. Legal victories also gave nonviolent activists greater moral authority in their confrontations with segregationists. In campaigns such as the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation and the 1961 Freedom Rides, activists could proclaim that they were simply exercising their constitutional rights, even as local authorities carted them off to jail.

The finding of Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the U.S. Supreme Court established the "separate but equal" doctrine, was not fully overturned for 58 years—until 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education declared the segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Token school desegregation occurred in Little Rock, Arkansas, and other parts of the South, but the pace of change was slow. Many Jim Crow laws remained on the books and were vigorously enforced well into the 1960s. The system would not be officially dismantled until after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 overturned state Jim Crow laws. This far-reaching federal legislation was prompted by the actions of the Freedom Riders and other direct-action campaigns in the civil rights movement, but it could not have happened without the series of victories won in the courts during earlier decades.

Photo: Getty Images

The Solid South

When the Kennedy administration finally chose to intervene on behalf of the Freedom Riders, they did so at significant political cost. In 1960, due to restrictive and racially discriminatory voter registration practices, the overwhelming majority of voters in the segregated South were white. This bloc of voters, the so-called "Solid South," was key to the fortunes of the Democratic Party.

Voters in these states helped elect John F. Kennedy as president in an extraordinarily close race against Republican candidate Richard Nixon. Segregationist Alabama governor John Patterson endorsed Kennedy early in the race. "I felt that if we ever got in a situation where we needed some understanding from the federal government in regard to our problems down here, we'd get an audience," Patterson said many years later.

But it was Patterson who chose to sever communications with the federal government, instructing his secretary to say that he had "gone fishing" when the President called after Freedom Riders were jailed in Birmingham, Alabama.

Despite this snub and the assault on justice department representative John Seigenthaler during the May 20 riot in Montgomery, Alabama, the administration continued to walk a fine line, mobilizing U.S. Marshals and National Guard units while entreating state officials to offer protection to the Freedom Riders themselves. The administration's tacit acceptance of the jail time in Mississippi for Freedom Riders in exchange for guarantees of their physical safety represented another attempt at compromise.

Over time, the Kennedy administration gradually aligned itself with civil rights activists, at the expense of their one-time allies in the segregated South. This trend continued during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texan instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Following Johnson's actions, the democrats lost the support of the Solid South in national presidential elections for most of the next half century.

When the Kennedy administration finally chose to intervene on behalf of the Freedom Riders, they did so at significant political cost. In 1960, due to restrictive and racially discriminatory voter registration practices, the overwhelming majority of voters in the segregated South were white. This bloc of voters, the so-called "Solid South," was key to the fortunes of the Democratic Party.

Voters in these states helped elect John F. Kennedy as president in an extraordinarily close race against Republican candidate Richard Nixon. Segregationist Alabama governor John Patterson endorsed Kennedy early in the race. "I felt that if we ever got in a situation where we needed some understanding from the federal government in regard to our problems down here, we'd get an audience," Patterson said many years later.

But it was Patterson who chose to sever communications with the federal government, instructing his secretary to say that he had "gone fishing" when the President called after Freedom Riders were jailed in Birmingham, Alabama.

Despite this snub and the assault on justice department representative John Seigenthaler during the May 20 riot in Montgomery, Alabama, the administration continued to walk a fine line, mobilizing U.S. Marshals and National Guard units while entreating state officials to offer protection to the Freedom Riders themselves. The administration's tacit acceptance of the jail time in Mississippi for Freedom Riders in exchange for guarantees of their physical safety represented another attempt at compromise.

Over time, the Kennedy administration gradually aligned itself with civil rights activists, at the expense of their one-time allies in the segregated South. This trend continued during the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, a Texan instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Following Johnson's actions, the democrats lost the support of the Solid South in national presidential elections for most of the next half century.

Photo: Getty Images

The Cold War

Initially civil rights were not a major concern for the Kennedy administration. Rather, Cold War politics were front and center. Staunchly anti-communist, John F. Kennedy used his inaugural address to speak about spreading freedom throughout the world—a goal contradicted by the large number of black Americans still lacking basic freedoms and civil rights.

The Freedom Rides did not come at a convenient time for the administration. The president was still smarting from the failed April 17 Bay of Pigs invasion, in which a group of U.S.-sponsored Cuban exiles had attempted to overthrow Castro's regime, and he was preparing for his upcoming Vienna summit with Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev on June 3, 1961. In the interim came headlines and televised images of a burning bus in Anniston, Alabama, and savage beatings in Birmingham, Alabama.

Communist nations were quick to see the propaganda value of the violence accompanying the Freedom Rides. The story of the Freedom Riders was broadcast around the world and the Kennedy administration found itself on the defensive. Robert F. Kennedy delivered an address for the Voice of America claiming that great progress had been made on the issue of race relations, and that a person of color might one day be president. Behind the scenes, the administration worked with leaders in the civil rights movement and white segregationist authorities to resolve the crisis with a minimum of violence and further headlines.

From this point forward, the events of the civil rights movement would play out on an international as well as a domestic stage.

Initially civil rights were not a major concern for the Kennedy administration. Rather, Cold War politics were front and center. Staunchly anti-communist, John F. Kennedy used his inaugural address to speak about spreading freedom throughout the world—a goal contradicted by the large number of black Americans still lacking basic freedoms and civil rights.

The Freedom Rides did not come at a convenient time for the administration. The president was still smarting from the failed April 17 Bay of Pigs invasion, in which a group of U.S.-sponsored Cuban exiles had attempted to overthrow Castro's regime, and he was preparing for his upcoming Vienna summit with Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev on June 3, 1961. In the interim came headlines and televised images of a burning bus in Anniston, Alabama, and savage beatings in Birmingham, Alabama.

Communist nations were quick to see the propaganda value of the violence accompanying the Freedom Rides. The story of the Freedom Riders was broadcast around the world and the Kennedy administration found itself on the defensive. Robert F. Kennedy delivered an address for the Voice of America claiming that great progress had been made on the issue of race relations, and that a person of color might one day be president. Behind the scenes, the administration worked with leaders in the civil rights movement and white segregationist authorities to resolve the crisis with a minimum of violence and further headlines.

From this point forward, the events of the civil rights movement would play out on an international as well as a domestic stage.

Photo: Getty Images

The Media

The Freedom Rides were successful in large part because they were able to engage the media and gain a sympathetic national audience. A handful of reporters and photographers from the black press and one freelance writer affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) accompanied the Riders on the buses during CORE's original May 4 Freedom Ride. Other than these journalists, initial news coverage of the Rides was mixed or strongly negative. Early news accounts criticized "extremists on both sides," equating civil rights activists with their segregationist opposition, and characterizing the Freedom Riders as "outside agitators."

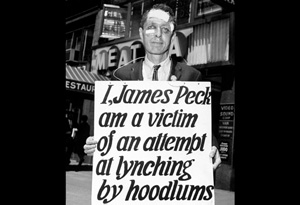

The images and eyewitness accounts of May 14, 1961 changed the country's consciousness. Footage of a burning bus in Anniston, Alabama, shocked the nation, as did photographs of the beatings inflicted during the riot at the Birmingham Trailways bus station and of the bandaged face of Freedom Rider James Peck lying in a hospital bed. Klan members attacked Birmingham Post-Herald photographer Tommy Langston along with other members of the media and attempted to destroy their film; miraculously, the roll of film inside Langston's smashed camera survived.

The impassioned eyewitness account of Howard K. Smith, a native southerner who had traveled to Birmingham to investigate allegations of lawlessness and racial intimidation from a neutral perspective helped shift public opinion. Just a few hours after the riot, he delivered his report over the national CBS radio network. Smith described a scene where "one passenger was knocked down at my feet by 12 of the hoodlums and his face was beaten and kicked until it was a bloody pulp." In the end, Smith abandoned journalistic objectivity, warning of "a dangerous confusion in the southern mind" while calling for legal change and presidential action to improve the situation.

While accounts of the Freedom Rides in the white southern press remained sharply negative and mocking, national media coverage became more favorable in the days that followed.

News reporters and photographers accompanied the Freedom Riders through most of the Rides' key events, from the May 21 riot and threatened mob violence in Montgomery, Alabama, all the way to the tense National Guard escort through Mississippi on May 24 and the breach of peace arrests that followed upon the Freedom Riders' arrival in Jackson. Movement leaders of the 1960s quickly absorbed the Freedom Riders' example; the most effective and best-remembered campaigns of the civil rights movement were those where the news media captured iconic images that the nation found impossible to ignore.

The Freedom Rides were successful in large part because they were able to engage the media and gain a sympathetic national audience. A handful of reporters and photographers from the black press and one freelance writer affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) accompanied the Riders on the buses during CORE's original May 4 Freedom Ride. Other than these journalists, initial news coverage of the Rides was mixed or strongly negative. Early news accounts criticized "extremists on both sides," equating civil rights activists with their segregationist opposition, and characterizing the Freedom Riders as "outside agitators."

The images and eyewitness accounts of May 14, 1961 changed the country's consciousness. Footage of a burning bus in Anniston, Alabama, shocked the nation, as did photographs of the beatings inflicted during the riot at the Birmingham Trailways bus station and of the bandaged face of Freedom Rider James Peck lying in a hospital bed. Klan members attacked Birmingham Post-Herald photographer Tommy Langston along with other members of the media and attempted to destroy their film; miraculously, the roll of film inside Langston's smashed camera survived.

The impassioned eyewitness account of Howard K. Smith, a native southerner who had traveled to Birmingham to investigate allegations of lawlessness and racial intimidation from a neutral perspective helped shift public opinion. Just a few hours after the riot, he delivered his report over the national CBS radio network. Smith described a scene where "one passenger was knocked down at my feet by 12 of the hoodlums and his face was beaten and kicked until it was a bloody pulp." In the end, Smith abandoned journalistic objectivity, warning of "a dangerous confusion in the southern mind" while calling for legal change and presidential action to improve the situation.

While accounts of the Freedom Rides in the white southern press remained sharply negative and mocking, national media coverage became more favorable in the days that followed.

News reporters and photographers accompanied the Freedom Riders through most of the Rides' key events, from the May 21 riot and threatened mob violence in Montgomery, Alabama, all the way to the tense National Guard escort through Mississippi on May 24 and the breach of peace arrests that followed upon the Freedom Riders' arrival in Jackson. Movement leaders of the 1960s quickly absorbed the Freedom Riders' example; the most effective and best-remembered campaigns of the civil rights movement were those where the news media captured iconic images that the nation found impossible to ignore.

Photo: Getty Images

Freedom to Travel

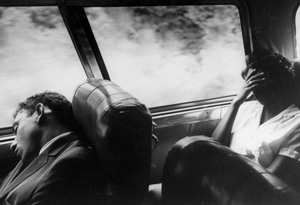

Since the institution of Jim Crow laws at the close of the 19th century, African-Americans in the South were forced to sit in the back of the bus and use separate waiting rooms, drinking fountains and rest rooms. In addition to these humiliations, the threat of violence was always present for black travelers.

On June 3, 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racial segregation on interstate buses as a violation of the interstate commerce clause. In December 1960, Boynton v. Virginia expanded that decision, outlawing segregated waiting rooms, lunch counters and restroom facilities for interstate passengers. However, both rulings were largely ignored in the Deep South.

On May 4, 1961, CORE began a racially integrated Freedom Ride on buses through the South to test whether buses and station facilities were compliant with the Supreme Court rulings. The ride was met with unprecedented violence, including the burning of a bus in Anniston, Alabama, and riots in Birmingham, Alabama, and Montgomery, Alabama. Further Rides followed as a way to draw national attention to the reality of segregation and put pressure on the federal government to enforce the law.

On September 22, 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) outlawed discriminatory seating practices on interstate bus transit and ordered the removal of "whites only" signs from interstate bus terminals by November 1, 1961. While pockets or racist resistance persisted for several years, eventually the signs came down.

More than simply a moral victory or a public relations coup, the victory won by the Freedom Riders changed the everyday lives of black travelers throughout the South, through the remainder of the 1960s and beyond.

Since the institution of Jim Crow laws at the close of the 19th century, African-Americans in the South were forced to sit in the back of the bus and use separate waiting rooms, drinking fountains and rest rooms. In addition to these humiliations, the threat of violence was always present for black travelers.

On June 3, 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racial segregation on interstate buses as a violation of the interstate commerce clause. In December 1960, Boynton v. Virginia expanded that decision, outlawing segregated waiting rooms, lunch counters and restroom facilities for interstate passengers. However, both rulings were largely ignored in the Deep South.

On May 4, 1961, CORE began a racially integrated Freedom Ride on buses through the South to test whether buses and station facilities were compliant with the Supreme Court rulings. The ride was met with unprecedented violence, including the burning of a bus in Anniston, Alabama, and riots in Birmingham, Alabama, and Montgomery, Alabama. Further Rides followed as a way to draw national attention to the reality of segregation and put pressure on the federal government to enforce the law.

On September 22, 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) outlawed discriminatory seating practices on interstate bus transit and ordered the removal of "whites only" signs from interstate bus terminals by November 1, 1961. While pockets or racist resistance persisted for several years, eventually the signs came down.

More than simply a moral victory or a public relations coup, the victory won by the Freedom Riders changed the everyday lives of black travelers throughout the South, through the remainder of the 1960s and beyond.

Photo: Getty Images

What Came Next?

The Freedom Rides represented a major evolution in the tactics and strategy of the civil rights movement. Thanks in large part to the phone calls and calm diplomacy of Nashville Student Movement leader Diane Nash, the Rides, initially a CORE project, became a coalition greater than any single organization's agenda—other groups knew the stakes of what CORE had put in motion and would not allow the campaign to fail. The Rides also marked an unprecedented level of engagement with the federal government and the beginning of a personal rapport between Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and movement leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr.

Efforts such as the SCLC's successful Birmingham Campaign of 1963 and the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches used many of the same techniques as the Freedom Rides, but the greatest impact of the Rides may have been the people who came out of them. In 1961, when Mississippi officials jailed Freedom Riders at Parchman State Prison on breach of peace charges, they hoped that the harsh conditions would break the Riders' spirits and squelch their movement. Instead, the experience proved to have the opposite effect—as prison became a crucible and training ground for the next generation of activists. John Lewis spoke at the March on Washington in 1963, played a pivotal role in organizing the Selma to Montgomery marches, and was elected in 1986 to the U.S. Congress. Stokely Carmichael became president of the SNCC in 1965 and would later coin the term "black power." Catherine Burks-Brooks was active in the Mississippi voter registration movement. These are just three names among many whose experiences on the buses and in jail prepared them for the civil rights struggles to come.

In the years to come, greater prizes would be won: passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawing racial discrimination in public and private facilities, passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawing discriminatory voting practices, and with them the end of legally enforced segregation as a way of life. The cost would grow as well: more beatings, more jail time and the murder of activists such as James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi in 1964 and Viola Liuzzo in Alabama in 1965. The Freedom Rides were a template and a training ground, forging new ties between groups and organizations while providing tangible evidence of what personal sacrifice could achieve.

The Freedom Rides represented a major evolution in the tactics and strategy of the civil rights movement. Thanks in large part to the phone calls and calm diplomacy of Nashville Student Movement leader Diane Nash, the Rides, initially a CORE project, became a coalition greater than any single organization's agenda—other groups knew the stakes of what CORE had put in motion and would not allow the campaign to fail. The Rides also marked an unprecedented level of engagement with the federal government and the beginning of a personal rapport between Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and movement leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr.

Efforts such as the SCLC's successful Birmingham Campaign of 1963 and the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches used many of the same techniques as the Freedom Rides, but the greatest impact of the Rides may have been the people who came out of them. In 1961, when Mississippi officials jailed Freedom Riders at Parchman State Prison on breach of peace charges, they hoped that the harsh conditions would break the Riders' spirits and squelch their movement. Instead, the experience proved to have the opposite effect—as prison became a crucible and training ground for the next generation of activists. John Lewis spoke at the March on Washington in 1963, played a pivotal role in organizing the Selma to Montgomery marches, and was elected in 1986 to the U.S. Congress. Stokely Carmichael became president of the SNCC in 1965 and would later coin the term "black power." Catherine Burks-Brooks was active in the Mississippi voter registration movement. These are just three names among many whose experiences on the buses and in jail prepared them for the civil rights struggles to come.

In the years to come, greater prizes would be won: passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawing racial discrimination in public and private facilities, passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawing discriminatory voting practices, and with them the end of legally enforced segregation as a way of life. The cost would grow as well: more beatings, more jail time and the murder of activists such as James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi in 1964 and Viola Liuzzo in Alabama in 1965. The Freedom Rides were a template and a training ground, forging new ties between groups and organizations while providing tangible evidence of what personal sacrifice could achieve.

Photo: Getty Images

Spirit of the Times

Midway between the 1954 Brown school desegregation decision and the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Rides captured the zeitgeist of the decade to come.

The emergence of 1960s counterculture and opposition to the Vietnam War were still several years away, but the seeds for these changes—and for the success of the Freedom Rides—were already present. When Americans saw the images of the burning bus in Anniston, Alabama, on television it brought the conflict into their living rooms and forced them to choose a side. The Freedom Rides were an early example of the way in which television could amplify the effects of social protest, just as images from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in 1965 or battle scenes from the 1968 Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War would shift public opinion in the years to come.

The election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 introduced a new brand of patriotic rhetoric, a challenge to all Americans to do more for their country and its stated ideals. In 1961, Cold War politics still reigned supreme on the national and international stage. Civil rights were not initially a major concern for Kennedy, but activists hoped that the new President might be more sympathetic to their cause than the Eisenhower administration. While the Kennedy administration's support was grudging and qualified, it nevertheless yielded concrete results, such as the ICC September 22, 1961, ruling to outlaw racial discrimination in interstate bus transit and remove "whites only" signs from interstate bus terminals, and the Kennedy-endorsed Voter Education Project that prefigured the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, and ultimately, the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Most important of all, the Freedom Riders were able to build on the momentum of previous legal victories and mass movements for civil rights and social justice.

Midway between the 1954 Brown school desegregation decision and the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Rides captured the zeitgeist of the decade to come.

The emergence of 1960s counterculture and opposition to the Vietnam War were still several years away, but the seeds for these changes—and for the success of the Freedom Rides—were already present. When Americans saw the images of the burning bus in Anniston, Alabama, on television it brought the conflict into their living rooms and forced them to choose a side. The Freedom Rides were an early example of the way in which television could amplify the effects of social protest, just as images from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in 1965 or battle scenes from the 1968 Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War would shift public opinion in the years to come.

The election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 introduced a new brand of patriotic rhetoric, a challenge to all Americans to do more for their country and its stated ideals. In 1961, Cold War politics still reigned supreme on the national and international stage. Civil rights were not initially a major concern for Kennedy, but activists hoped that the new President might be more sympathetic to their cause than the Eisenhower administration. While the Kennedy administration's support was grudging and qualified, it nevertheless yielded concrete results, such as the ICC September 22, 1961, ruling to outlaw racial discrimination in interstate bus transit and remove "whites only" signs from interstate bus terminals, and the Kennedy-endorsed Voter Education Project that prefigured the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, and ultimately, the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Most important of all, the Freedom Riders were able to build on the momentum of previous legal victories and mass movements for civil rights and social justice.

Photo: Getty Images

Victory for Nonviolence

The Freedom Rides demonstrated the power of nonviolent direct action to achieve strategic victory. From its founding by pacifists in 1942, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was committed to practicing methods of nonviolent direct action. The Rev. Jim Lawson, part of the second wave of Freedom Riders, had studied nonviolent philosophy and techniques in India and trained future leaders of the Nashville Student Movement.

The Freedom Riders were able to remain nonviolent even when their lives were in danger. Their courage and stoicism, even when beaten and bloodied, left a deep impression on the nation and the world. Nonviolence drew a stark contrast between the actions of the Freedom Riders and those of their segregationist foes, while at the same time bringing the injustice of racial oppression into the spotlight.

The success of the Freedom Rides showed that nonviolent direct action could do more than simply claim the moral high ground; in many situations, it could deliver better tactical results than either violent confrontation or gradual change through established legal mechanisms.

Fresh waves of Riders would arrive to take the places of those Riders who had already been injured and jailed. Movement leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. who initially considered the Freedom Rides too risky became outspoken supporters, paving the way for nonviolent actions like the Birmingham campaign of 1963 and the Selma to Montgomery marches for voting rights of 1965.

The Freedom Rides demonstrated the power of nonviolent direct action to achieve strategic victory. From its founding by pacifists in 1942, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was committed to practicing methods of nonviolent direct action. The Rev. Jim Lawson, part of the second wave of Freedom Riders, had studied nonviolent philosophy and techniques in India and trained future leaders of the Nashville Student Movement.

The Freedom Riders were able to remain nonviolent even when their lives were in danger. Their courage and stoicism, even when beaten and bloodied, left a deep impression on the nation and the world. Nonviolence drew a stark contrast between the actions of the Freedom Riders and those of their segregationist foes, while at the same time bringing the injustice of racial oppression into the spotlight.

The success of the Freedom Rides showed that nonviolent direct action could do more than simply claim the moral high ground; in many situations, it could deliver better tactical results than either violent confrontation or gradual change through established legal mechanisms.

Fresh waves of Riders would arrive to take the places of those Riders who had already been injured and jailed. Movement leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. who initially considered the Freedom Rides too risky became outspoken supporters, paving the way for nonviolent actions like the Birmingham campaign of 1963 and the Selma to Montgomery marches for voting rights of 1965.

Democracy in Action

The Freedom Rides brought together people of different races, religions, cultures and economic backgrounds from across the United States. Unlike most other campaigns of the civil rights movement, a single organization or charismatic leader did not dominate; instead, history was made by courageous men and women who chose to join the Rides, alone or as part of groups such as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the closely linked Nashville Student Movement. Many Riders were students in their late teens or early 20s.

The key lesson of the Rides was "the ability of ordinary citizens to affect public policy" wrote historian Raymond Arsenault in his book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Individuals without legal training or political connections were nevertheless able to make headlines and confront an unjust system. The change that they created was democratic in its most direct sense—as the actions of ordinary people compelled established movement leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and government officials like John F. Kennedy Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy to respond. Raymond argued that the Freedom Riders, more so than any other activists of the time, prefigured the "rights revolution" and the movements for feminism, the environment, gay and lesbian rights, the rights of the disabled and the end of the Vietnam War.

The integrated civil rights movement of the early 1960s would eventually be tested past its limits, splitting into black power and other factions. But during the Freedom Rides, the coalition held.

More on the Freedom Rides

Retrace the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders: Then and now

Read an excerpt from Freedom Riders

The Freedom Rides brought together people of different races, religions, cultures and economic backgrounds from across the United States. Unlike most other campaigns of the civil rights movement, a single organization or charismatic leader did not dominate; instead, history was made by courageous men and women who chose to join the Rides, alone or as part of groups such as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the closely linked Nashville Student Movement. Many Riders were students in their late teens or early 20s.

The key lesson of the Rides was "the ability of ordinary citizens to affect public policy" wrote historian Raymond Arsenault in his book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Individuals without legal training or political connections were nevertheless able to make headlines and confront an unjust system. The change that they created was democratic in its most direct sense—as the actions of ordinary people compelled established movement leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and government officials like John F. Kennedy Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy to respond. Raymond argued that the Freedom Riders, more so than any other activists of the time, prefigured the "rights revolution" and the movements for feminism, the environment, gay and lesbian rights, the rights of the disabled and the end of the Vietnam War.

The integrated civil rights movement of the early 1960s would eventually be tested past its limits, splitting into black power and other factions. But during the Freedom Rides, the coalition held.

More on the Freedom Rides

Retrace the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders: Then and now

Read an excerpt from Freedom Riders

ONLINE CONTENT COURTESY OF

"FREEDOM RIDERS"

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, A WGBH PRODUCTION FOR PBS

"FREEDOM RIDERS"

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, A WGBH PRODUCTION FOR PBS