Sex Offenders Confined on an Island

One hour outside of Seattle, there's a small island in the Puget Sound that people rarely visit. Some residents rarely leave.

This place, McNeil Island, is home to a corrections center that houses hundreds of the state's most dangerous sexual predators.

Cameras are almost never allowed inside this controversial facility, but in February 2010, correspondent Lisa Ling was granted rare access inside the residents' rooms, common areas and therapy sessions.

McNeil Island is only accessible by ferry. At the port, Lisa is met by Kelly Cunningham, the superintendent of this special commitment center. "[It's] a mental health facility for Level 3 sexual predators," Lisa says. "The worst of the worst."

Every person confined in this facility has served time for sexual offenses. But, when their prison sentences were up, they weren't set free. Instead, they went before a review board and a judge. If these violent sexual predators were deemed too dangerous to return to society, they were committed to McNeil Island indefinitely.

"It's not voluntary, not by any means," Kelly says. "Our primary purpose is public safety. We don't want any more victims."

This place, McNeil Island, is home to a corrections center that houses hundreds of the state's most dangerous sexual predators.

Cameras are almost never allowed inside this controversial facility, but in February 2010, correspondent Lisa Ling was granted rare access inside the residents' rooms, common areas and therapy sessions.

McNeil Island is only accessible by ferry. At the port, Lisa is met by Kelly Cunningham, the superintendent of this special commitment center. "[It's] a mental health facility for Level 3 sexual predators," Lisa says. "The worst of the worst."

Every person confined in this facility has served time for sexual offenses. But, when their prison sentences were up, they weren't set free. Instead, they went before a review board and a judge. If these violent sexual predators were deemed too dangerous to return to society, they were committed to McNeil Island indefinitely.

"It's not voluntary, not by any means," Kelly says. "Our primary purpose is public safety. We don't want any more victims."

After docking on McNeil Island, Lisa tours the $60 million facility with Kelly. First, she visits the control center where guards monitor 200 security cameras. "There are only three other facilities in the country that have a similar system," Kelly says. "They're all super max prisons."

Despite the need for high-level security, most residents roam freely around the 5-acre campus. Though they're allowed more freedom than prison inmates, all residents must follow some strict rules. Phone calls and Internet use are strictly monitored, and sex with other residents is forbidden.

"Something as seemingly benign as a catalog isn't allowed," Kelly says. "We've had residents take those catalogs and tear out the pictures of the little kids in their underwear and use them for deviant fantasies."

Lisa learns that about 60 percent of McNeil Island's residents are pedophiles. "This assignment was certainly one of the most disturbing assignments of my career, especially to be amongst so many people with literally thousands of offenses toward children," she says. "But I really tried to approach this with an open mind. ... I believe the only way to be able to treat this issue is if we understand the behavior."

Despite the need for high-level security, most residents roam freely around the 5-acre campus. Though they're allowed more freedom than prison inmates, all residents must follow some strict rules. Phone calls and Internet use are strictly monitored, and sex with other residents is forbidden.

"Something as seemingly benign as a catalog isn't allowed," Kelly says. "We've had residents take those catalogs and tear out the pictures of the little kids in their underwear and use them for deviant fantasies."

Lisa learns that about 60 percent of McNeil Island's residents are pedophiles. "This assignment was certainly one of the most disturbing assignments of my career, especially to be amongst so many people with literally thousands of offenses toward children," she says. "But I really tried to approach this with an open mind. ... I believe the only way to be able to treat this issue is if we understand the behavior."

While confined on McNeil Island, residents have the option of entering the sexual predator treatment program. If they attend therapy sessions and meet with counselors, they will be reevaluated and may have the option of leaving the facility.

If they don't get treatment, they will be confined to this commitment center indefinitely.

Since this corrections center opened in 1990, Lisa says that only four residents have been allowed to leave unconditionally. Sixteen other people have left the island, but they're still under supervision.

While some people applaud measures like McNeil Island, others think molesters' indefinite confinement violates their legal rights. "This is a very controversial program because all of these people have already served their sentence," Lisa says. "So in a sense, they're being sent to this island to prevent them from crimes that they may commit."

If they don't get treatment, they will be confined to this commitment center indefinitely.

Since this corrections center opened in 1990, Lisa says that only four residents have been allowed to leave unconditionally. Sixteen other people have left the island, but they're still under supervision.

While some people applaud measures like McNeil Island, others think molesters' indefinite confinement violates their legal rights. "This is a very controversial program because all of these people have already served their sentence," Lisa says. "So in a sense, they're being sent to this island to prevent them from crimes that they may commit."

Lisa says it costs taxpayers $165,000 per resident per year to keep them on the island. Some of this money goes toward treatment. "There are some who say that taxpayer dollars shouldn't fund treatment," she says. "That people who commit crimes against children or sexual crimes should just remain in prison or remain locked up without services."

Dr. Carey Sturgeon, the clinical director for McNeil Island's special treatment program, disagrees. "I guess I want to live in a world where we believe in grace and [believe] people can change," she says. "Knowing that treatment can work for sex offenders is one way of living that."

For the first time, Dr. Sturgeon allows cameras to film her therapy session with a group of convicted sex offenders. Since therapy is voluntary, Lisa says less than half of the residents participate. The ones who do are required to go to group sessions three times a week.

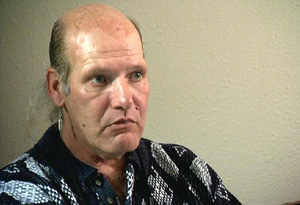

While sitting in on the session, Lisa meets Brent, a man who has multiple convictions against both boys and girls. "When Brent first started talking, it was very uncomfortable for me," she says. "It felt very, very awkward sitting there listening to the things that he had done."

After therapy, Brent agreed to talk more with Lisa in his room.

Dr. Carey Sturgeon, the clinical director for McNeil Island's special treatment program, disagrees. "I guess I want to live in a world where we believe in grace and [believe] people can change," she says. "Knowing that treatment can work for sex offenders is one way of living that."

For the first time, Dr. Sturgeon allows cameras to film her therapy session with a group of convicted sex offenders. Since therapy is voluntary, Lisa says less than half of the residents participate. The ones who do are required to go to group sessions three times a week.

While sitting in on the session, Lisa meets Brent, a man who has multiple convictions against both boys and girls. "When Brent first started talking, it was very uncomfortable for me," she says. "It felt very, very awkward sitting there listening to the things that he had done."

After therapy, Brent agreed to talk more with Lisa in his room.

Unlike some residents, Brent, a father of three, asked to be committed to McNeil Island Corrections Center after he was arrested. Over the years, he says he's molested more than 40 children...but never his own.

When Brent, a sexual abuse survivor himself, was around children he was attracted to, he says he would experience sexual preoccupation. "[I was] putting them in a role, elevating them to like a partner instead of seeing them as a child," he says.

Before his confinement, Brent says he would go to great lengths to spend time with his victims. He even sought them out at church. "Some of my victims attended the same church that I did," he says. "So that was a place for me to go and spend time with them."

With almost every victim—up to 98 percent—Brent says the assaults involved sexual penetration.

"If you are able to get off this island, do you think you'll ever be able to be around children?" Lisa asks.

"Realistically? Probably not. Not in the sense of having interpersonal relationships," he says. "I never offended against my children. They're adults now. But to be around say, my grandkids? No. My nephews? Nieces? No. No. That's not an option, and that's a tough one to take."

When Brent, a sexual abuse survivor himself, was around children he was attracted to, he says he would experience sexual preoccupation. "[I was] putting them in a role, elevating them to like a partner instead of seeing them as a child," he says.

Before his confinement, Brent says he would go to great lengths to spend time with his victims. He even sought them out at church. "Some of my victims attended the same church that I did," he says. "So that was a place for me to go and spend time with them."

With almost every victim—up to 98 percent—Brent says the assaults involved sexual penetration.

"If you are able to get off this island, do you think you'll ever be able to be around children?" Lisa asks.

"Realistically? Probably not. Not in the sense of having interpersonal relationships," he says. "I never offended against my children. They're adults now. But to be around say, my grandkids? No. My nephews? Nieces? No. No. That's not an option, and that's a tough one to take."

Out of the nearly 300 residents on McNeil Island, only one is a woman. Until now, Laura has never spoken to a reporter about her crimes against children.

In 1989, Laura was sent to prison for the first-degree rape of a child. In the past, she took responsibility for 15 offenses, but she says she's guilty of many more. "I would say, as I said in all of my testings and stuff, that I've done, I would say, 100 or more," she says.

Before she was arrested, Laura was a caretaker for babies and toddlers. She admits she sexually abused her young victims while babysitting. "It's not like every time I see a kid, I get aroused and know I want to hurt them," she says. "It's being in the line of their care, like having to bathe them or change them. ... I did bad things, really bad things."

Once, Laura says she almost killed one of her victims by suffocating her with a pillow. "I had a friend there, so that got interrupted, which I was very glad for after the fact," she says.

If she hadn't been caught, Laura says she doesn't think anything would have stopped her."I didn't need to groom my victims because they were so young," she says. "But I did have to groom their parents."

In 1989, Laura was sent to prison for the first-degree rape of a child. In the past, she took responsibility for 15 offenses, but she says she's guilty of many more. "I would say, as I said in all of my testings and stuff, that I've done, I would say, 100 or more," she says.

Before she was arrested, Laura was a caretaker for babies and toddlers. She admits she sexually abused her young victims while babysitting. "It's not like every time I see a kid, I get aroused and know I want to hurt them," she says. "It's being in the line of their care, like having to bathe them or change them. ... I did bad things, really bad things."

Once, Laura says she almost killed one of her victims by suffocating her with a pillow. "I had a friend there, so that got interrupted, which I was very glad for after the fact," she says.

If she hadn't been caught, Laura says she doesn't think anything would have stopped her."I didn't need to groom my victims because they were so young," she says. "But I did have to groom their parents."

Laura says she groomed low-income, drug-addicted moms by offering them drugs and alcohol. Now, she warns other parents of making the same mistakes.

"Don't just let any Joe Blow babysit your kids. If your kids are uncomfortable around that person or they don't want to leave with that person, don't make them go," she says. "I think that there are actually more women out there just like me. I just think they haven't been caught."

Who are the most vulnerable victims? Laura says it's the children who aren't getting the love and attention they need at home.

"Back when I was offending, if I saw a parent who seemed negligent or they didn't want to be bothered with their kid or they didn't want to go to the park or they didn't want to play with them or they were messy and dirty or they needed a bath, those were the kind of people that I targeted," she says.

Watch Oprah's conversation with child molesters.

Dr. Laura Berman on the aftermath of sexual abuse

"Don't just let any Joe Blow babysit your kids. If your kids are uncomfortable around that person or they don't want to leave with that person, don't make them go," she says. "I think that there are actually more women out there just like me. I just think they haven't been caught."

Who are the most vulnerable victims? Laura says it's the children who aren't getting the love and attention they need at home.

"Back when I was offending, if I saw a parent who seemed negligent or they didn't want to be bothered with their kid or they didn't want to go to the park or they didn't want to play with them or they were messy and dirty or they needed a bath, those were the kind of people that I targeted," she says.

Watch Oprah's conversation with child molesters.

Dr. Laura Berman on the aftermath of sexual abuse