Conquering Addiction

Many drug addicts wage a private battle—both to conquer their addiction and to keep it from their families. As new technology provides more weapons in the war against substance addiction, former drug users are telling their stories…bringing their secret world to light.

The acclaimed HBO series, Addicted, follows the real-life struggles of 30 drug addicts in their daily lives—from getting high to hitting rock bottom. And for most, the road to recovery is a long one.

From the outside, Rick seemed to have a perfect life. As a senior correspondent for the news show Inside Edition, he traveled the globe, interviewed presidents, lived in a big house and had a beautiful family.

The acclaimed HBO series, Addicted, follows the real-life struggles of 30 drug addicts in their daily lives—from getting high to hitting rock bottom. And for most, the road to recovery is a long one.

From the outside, Rick seemed to have a perfect life. As a senior correspondent for the news show Inside Edition, he traveled the globe, interviewed presidents, lived in a big house and had a beautiful family.

"What nobody knew at the time was that I was a crack cocaine addict," Rick says. "A hard-core crack cocaine addict." Rick says he got hooked on the drug after reporting on narcotics busts. "I tried it, and the next day I was on the same streets [as the raid], buying it myself, and I was an addict from then on," he says.

Rick describes himself as having been a "functional addict," doing drugs mostly at night. He says he loathed himself for this double life—reporting on crack house busts while he was doing the drug himself. "I felt like a horrible hypocrite throughout that time. It was hard to live with, but that also fed into the addiction," he says.

At an anti-drug event in Houston, Rick was offered the interview of a lifetime—President George H.W. Bush. But, what should have been a career high became a personal low point. "I had been smoking crack an hour beforehand, so I was high when I interviewed the president," he says.

Despite his guilt and the destruction of his family life, Rick continued his downward spiral. "It is a psychological addiction," he says. "And I honestly can't tell you why I couldn't stop." Rick says, finally, after 10 years—and spending nearly $250,000 on crack—he kicked the habit. He says he has been clean for nearly eight years.

Rick describes himself as having been a "functional addict," doing drugs mostly at night. He says he loathed himself for this double life—reporting on crack house busts while he was doing the drug himself. "I felt like a horrible hypocrite throughout that time. It was hard to live with, but that also fed into the addiction," he says.

At an anti-drug event in Houston, Rick was offered the interview of a lifetime—President George H.W. Bush. But, what should have been a career high became a personal low point. "I had been smoking crack an hour beforehand, so I was high when I interviewed the president," he says.

Despite his guilt and the destruction of his family life, Rick continued his downward spiral. "It is a psychological addiction," he says. "And I honestly can't tell you why I couldn't stop." Rick says, finally, after 10 years—and spending nearly $250,000 on crack—he kicked the habit. He says he has been clean for nearly eight years.

Crystal's drug addiction began when she tried crystal methamphetamine at age 20. "After that first time, I swore to myself I would never do it again," she says. "And it didn't happen that way."

Soon, Crystal's entire life became about getting the next big high. "I started off snorting it and the high wasn't good enough, so then I started smoking it. It wasn't good enough. Next thing I know someone introduced a needle to me," she says.

Though Crystal says the high was better when she used the needle, she quickly "blew out" the veins in her arms—so she began injecting the drug into her neck.

In Addicted, Crystal talks on camera about the effect the drug has on her…while shooting up. "People don't understand how we can get addicted to this, but I feel so good right now, better than any sober person has ever felt their whole entire life." Crystal says that at the time she was taking as much as three or four grams of meth per day, putting as much as half a gram into her veins at a time.

At the end of filming, Crystal decided to give up drugs for good. She says she has been clean for more than a year. While seeing herself on film is hard to watch, she hopes her story will have a positive effect for others. "I was doing all this bad. I was tearing my life up, but if I [can] help somebody else out, it [will] be worth it," she says.

Soon, Crystal's entire life became about getting the next big high. "I started off snorting it and the high wasn't good enough, so then I started smoking it. It wasn't good enough. Next thing I know someone introduced a needle to me," she says.

Though Crystal says the high was better when she used the needle, she quickly "blew out" the veins in her arms—so she began injecting the drug into her neck.

In Addicted, Crystal talks on camera about the effect the drug has on her…while shooting up. "People don't understand how we can get addicted to this, but I feel so good right now, better than any sober person has ever felt their whole entire life." Crystal says that at the time she was taking as much as three or four grams of meth per day, putting as much as half a gram into her veins at a time.

At the end of filming, Crystal decided to give up drugs for good. She says she has been clean for more than a year. While seeing herself on film is hard to watch, she hopes her story will have a positive effect for others. "I was doing all this bad. I was tearing my life up, but if I [can] help somebody else out, it [will] be worth it," she says.

For William, the fight against using crack cocaine is a recent one—he has only been clean for three weeks. "I still struggle from day to day," he says. "It's very hard."

Though his attempt to stay clean is only a few weeks old, William says this isn't the first time he has given up drugs. "I know what it's like to be clean. It's something that I actually chase after," he says. At one time, William was able to stay drug-free for two and a half years. He got married, relocated and started a family. For a while, things with his wife and three kids were "great"—until he couldn't resist anymore. "Using actually took my wife from me, in a way," he says.

While William admits that life off drugs feels better, he just couldn't stop. "What I'm trying to do when I use is escape for a minute, escape my reality," he says.

Though his attempt to stay clean is only a few weeks old, William says this isn't the first time he has given up drugs. "I know what it's like to be clean. It's something that I actually chase after," he says. At one time, William was able to stay drug-free for two and a half years. He got married, relocated and started a family. For a while, things with his wife and three kids were "great"—until he couldn't resist anymore. "Using actually took my wife from me, in a way," he says.

While William admits that life off drugs feels better, he just couldn't stop. "What I'm trying to do when I use is escape for a minute, escape my reality," he says.

When Tom began drinking as a teenager, he knew he was becoming addicted—but it didn't seem to matter. "I never made any bones about it," he says. "My posture was, 'I don't get in trouble with the law. Financially, it's not that much of a burden. I don't get into altercations with family or friends—where's the harm?'"

Tom says he was addicted to alcohol for 50 years, and no one in his family made a real effort to stop him. "I'd say, 'Mom, you know, some people fish. Some people hunt. Some people collect stamps. I just happen to drink as a hobby,'" he says.

In the decade leading to his ultimate sobriety, Tom was so hooked that he would wake up in the middle of the night to get a drink—sometimes up to a fifth of whiskey straight from the bottle. After ruining his marriage and having health problems, Tom says he realized his addiction was killing him.

"My health started deteriorating so bad. … I'd always been kind of an upbeat sort of person, but I was getting kind of depressed because I knew that I wasn't doing the things that I wanted to do," he says. "I wasn't achieving anything out of life. I'd drink, sleep, get up and drink again."

Finally, Tom decided it was time to take action. He enrolled in a research program and was given experimental drugs that he claims helped stop his cravings. He says he has not had a drink in two years.

Tom says he was addicted to alcohol for 50 years, and no one in his family made a real effort to stop him. "I'd say, 'Mom, you know, some people fish. Some people hunt. Some people collect stamps. I just happen to drink as a hobby,'" he says.

In the decade leading to his ultimate sobriety, Tom was so hooked that he would wake up in the middle of the night to get a drink—sometimes up to a fifth of whiskey straight from the bottle. After ruining his marriage and having health problems, Tom says he realized his addiction was killing him.

"My health started deteriorating so bad. … I'd always been kind of an upbeat sort of person, but I was getting kind of depressed because I knew that I wasn't doing the things that I wanted to do," he says. "I wasn't achieving anything out of life. I'd drink, sleep, get up and drink again."

Finally, Tom decided it was time to take action. He enrolled in a research program and was given experimental drugs that he claims helped stop his cravings. He says he has not had a drink in two years.

Cheryl traces the source of her 15-year cocaine addiction back to her childhood. When she was 8 years old, Cheryl says she was molested—causing emotional and physical trauma that destroyed her self-esteem. "My first drug was fear," she says. To cope with her abuse, Cheryl says she began smoking marijuana, drinking alcohol and having promiscuous sex as a teenager. Then, she says she turned to cocaine. "I believe that I made a willing choice to get high because I just didn't want to feel it anymore," she says.

Cheryl's cocaine addiction took its toll on her entire family—and she says one of her lowest points was her daughter's eighth birthday. With no money to throw a party, Cheryl raised the cash she needed by having a garage sale. With money in hand, she left to buy her daughter a birthday cake—but never made it back. "I went to get high," she says. "The money sat in my hand, and the drug sat on my heart, and one outweighed the other."

Although she is clean now, Cheryl says her life might have taken a different course had she gotten help or therapy earlier—but she was too terrified to ask for it. "I slept and I ate and I drank fear [after the abuse]," she says. "I love my children. But I hated myself so greatly that I never could understand … that I was not [to blame for what happened to me]," she says.

Cheryl's cocaine addiction took its toll on her entire family—and she says one of her lowest points was her daughter's eighth birthday. With no money to throw a party, Cheryl raised the cash she needed by having a garage sale. With money in hand, she left to buy her daughter a birthday cake—but never made it back. "I went to get high," she says. "The money sat in my hand, and the drug sat on my heart, and one outweighed the other."

Although she is clean now, Cheryl says her life might have taken a different course had she gotten help or therapy earlier—but she was too terrified to ask for it. "I slept and I ate and I drank fear [after the abuse]," she says. "I love my children. But I hated myself so greatly that I never could understand … that I was not [to blame for what happened to me]," she says.

For anyone who has struggled with addiction or loved an addict, the number one question most people want answered is, Why can't they stop?

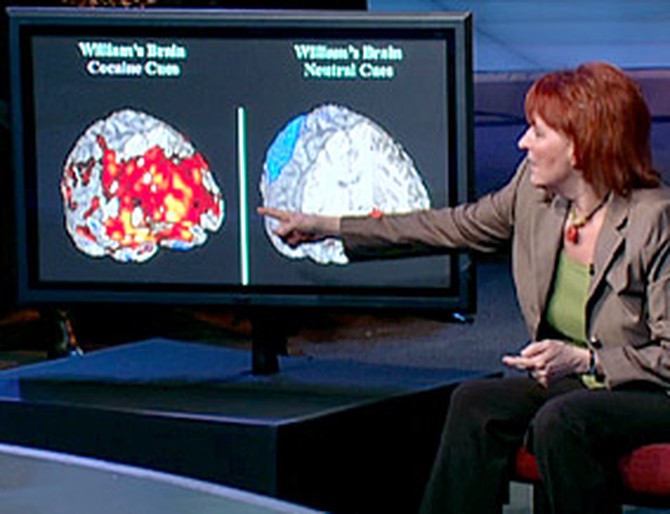

Dr. Anna Rose Childress, a professor who specializes in brain behavior at the Pennsylvania VA Addiction Treatment Research Center, has been using the latest scientific technology to study addicts' brains and determine what happens when a person is struggling with substance abuse.

To see what's going on inside the brain, Dr. Childress takes pictures of an addict's brain reacting to images both related and unrelated to drug use. Then, the researchers compare the way the brain reacts to each cue to determine the areas that are affected.

Since the study began, Dr. Childress has worked with cocaine, marijuana, nicotine and heroin addicts. The substances may vary, but the results do not. Dr. Childress says that in most cases, the brain was "compromised."

"The person [who is addicted] is actually not making choices in the rational way," she says. "This brain is a different brain, and we think the brain may be different when you walk into the world in terms of your ability to manage some of your impulses. But certainly after it's been exposed to drugs, there are important changes."

The brain functions that are affected are the same ones that help us maintain relationships and seek out the things we need to survive, like food and sleep. "That kind of strong, strong desire is a part of this system in the brain that now gets upturned," Dr. Childress says. "It gets inverted. It gets hijacked, essentially. So the drug does have a direct impact on the brain."

Dr. Anna Rose Childress, a professor who specializes in brain behavior at the Pennsylvania VA Addiction Treatment Research Center, has been using the latest scientific technology to study addicts' brains and determine what happens when a person is struggling with substance abuse.

To see what's going on inside the brain, Dr. Childress takes pictures of an addict's brain reacting to images both related and unrelated to drug use. Then, the researchers compare the way the brain reacts to each cue to determine the areas that are affected.

Since the study began, Dr. Childress has worked with cocaine, marijuana, nicotine and heroin addicts. The substances may vary, but the results do not. Dr. Childress says that in most cases, the brain was "compromised."

"The person [who is addicted] is actually not making choices in the rational way," she says. "This brain is a different brain, and we think the brain may be different when you walk into the world in terms of your ability to manage some of your impulses. But certainly after it's been exposed to drugs, there are important changes."

The brain functions that are affected are the same ones that help us maintain relationships and seek out the things we need to survive, like food and sleep. "That kind of strong, strong desire is a part of this system in the brain that now gets upturned," Dr. Childress says. "It gets inverted. It gets hijacked, essentially. So the drug does have a direct impact on the brain."

William is one of the addicts who participated in Dr. Childress's study. While examining William's brain, she flashed cocaine cues—images of people he had used the drug with or things that reminded him of cocaine—onto a screen for just 33 milliseconds at a time. Most people wouldn't even be able to recognize what they were seeing, but William's brain was well aware.

"For someone with a history of cocaine, there's an intense arousal that sets up in milliseconds," Dr. Childress says. "These cues say, 'This is more important than your children, than your spouse, than your job…pursue this.' From the brain's perspective, this is the important thing."

Photos of William's brain show that there was a surge of chemicals released when he saw the powerful cues, which Dr. Childress calls the "go state." For the first time in human history, researchers can now see what's happening inside the brain, identify the targets and see what they need to address.

"We're really excited that we can both calm down the go state, but also bolster the brakes," she says. "One of the things that we've been able to see is that people with addictions—their brakes aren't so good. So [there are] two ways that you can help the car—one is to take your foot off the accelerator. Another way is to put on the brakes."

Dr. Childress's goal is to treat addiction with medications that curb the craving. "Instead of it being so compelling and something that would cause you to go away from your family and your children, with medication, you can get a brain now that's sort of back down to, 'This is not so exciting. I can take this or leave this,'" she says.

"For someone with a history of cocaine, there's an intense arousal that sets up in milliseconds," Dr. Childress says. "These cues say, 'This is more important than your children, than your spouse, than your job…pursue this.' From the brain's perspective, this is the important thing."

Photos of William's brain show that there was a surge of chemicals released when he saw the powerful cues, which Dr. Childress calls the "go state." For the first time in human history, researchers can now see what's happening inside the brain, identify the targets and see what they need to address.

"We're really excited that we can both calm down the go state, but also bolster the brakes," she says. "One of the things that we've been able to see is that people with addictions—their brakes aren't so good. So [there are] two ways that you can help the car—one is to take your foot off the accelerator. Another way is to put on the brakes."

Dr. Childress's goal is to treat addiction with medications that curb the craving. "Instead of it being so compelling and something that would cause you to go away from your family and your children, with medication, you can get a brain now that's sort of back down to, 'This is not so exciting. I can take this or leave this,'" she says.

It may be years before experimental treatments and prescription medications are available to all mothers, fathers and friends struggling with an addiction. For now, Dr. Michael Dennis, a psychologist who specializes in teen addiction at the Lighthouse Institute in Bloomington, Illinois, says the sooner you intervene, the better.

Although there isn't one answer or solution for every addict, Dr. Dennis says 90 percent of the people who become dependent on a drug started using when they were under 18. Fifty percent of addicts began using drugs when they were 15 years old…or younger.

If someone you love suffers a relapse, Dr. Dennis says his or her chances of recovery increase the sooner you reintervene.

Even if someone has completed a rehabilitation program, triggers in the outside world can cause a relapse. "Rehab is just a tool," Rick says. "The doors open up and you walk out. If you're just holding a tool, and no one's out there to help you support it, you're going to fall right off the wagon."

Although there isn't one answer or solution for every addict, Dr. Dennis says 90 percent of the people who become dependent on a drug started using when they were under 18. Fifty percent of addicts began using drugs when they were 15 years old…or younger.

If someone you love suffers a relapse, Dr. Dennis says his or her chances of recovery increase the sooner you reintervene.

Even if someone has completed a rehabilitation program, triggers in the outside world can cause a relapse. "Rehab is just a tool," Rick says. "The doors open up and you walk out. If you're just holding a tool, and no one's out there to help you support it, you're going to fall right off the wagon."

After years of lying and manipulating, many addicts end up divorced and estranged from their loved ones…even their children.

"You actually end up believing your own lies. You become part of them," William says. "They become your reality, actually, after a while."

Resisting drugs or alcohol is a daily struggle for most addicts, but Rick says there's one thing that's even more difficult than staying clean.

"Even harder than quitting the drug, getting off the drug, is forgiving yourself," Rick says. "I'm almost eight years clean, and I still loathe myself at times because of what I did years ago. I may be out helping kids every day and speaking at schools. … But I still go home at night and say, 'It's not enough. I don't forgive myself yet.'"

"You actually end up believing your own lies. You become part of them," William says. "They become your reality, actually, after a while."

Resisting drugs or alcohol is a daily struggle for most addicts, but Rick says there's one thing that's even more difficult than staying clean.

"Even harder than quitting the drug, getting off the drug, is forgiving yourself," Rick says. "I'm almost eight years clean, and I still loathe myself at times because of what I did years ago. I may be out helping kids every day and speaking at schools. … But I still go home at night and say, 'It's not enough. I don't forgive myself yet.'"

Published 04/09/2007