Class in America

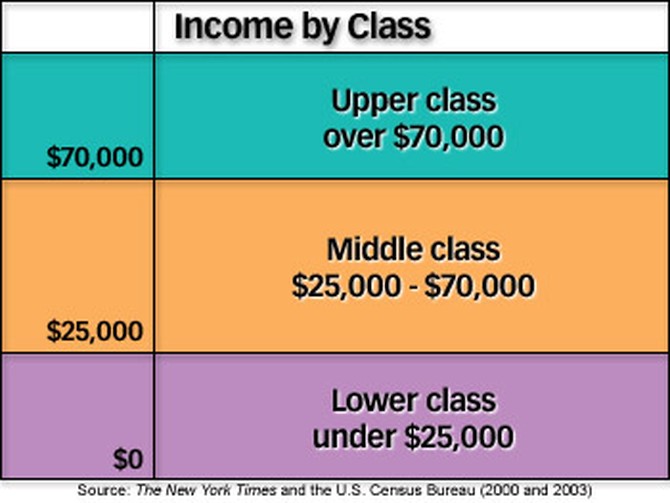

According to The New York Times' Class Matters series and the U.S. Census Bureau statistics from 2000 and 2003, if you make up to $25,000 per year, you are lower class; if you make between $25,000–$70,000, you are middle class; if you make over $70,000 per year, you are upper class.

Can you tell a person's class by the way they look or talk? An audience member named Patience says she believes things like hair plastered up with hairspray, long acrylic fingernails and crude table manners are all signs of being lower class. She also says poor diction and bad grammar are class indicators. "English is our friend and so we don't have to fight it," says Patience. "You can use it to serve you—to expand your opportunities as a person."

In reality, what sets the different classes apart is more than skin deep.

In reality, what sets the different classes apart is more than skin deep.

Although Carrie and Erin are both stay-at-home moms living in the Chicago area, they live worlds apart. Carrie and her husband, Jerry, are working class parents who live with their two sons (left) in Cicero, Illinois. Due to the high cost of daycare, Carrie stays home to take care of the kids while Jerry works more than 60 hours a week between two jobs. Their neighborhood is largely made up of factories and elderly residents. Carrie says gangs and crime keep her from letting her boys play outside unsupervised.

Erin, her husband, Kip, and their five children (right) are an upper-middle class family who live in the affluent suburb of Naperville, Illinois. Erin stays busy taking care of the kids while Kip works as a managing director of insurance. In her neighborhood, Erin says furniture, cars, engagement rings and well-manicured lawns are all signs of status. She says her neighborhood is a safe place for her kids to play outside and ride bikes unattended.

Erin, her husband, Kip, and their five children (right) are an upper-middle class family who live in the affluent suburb of Naperville, Illinois. Erin stays busy taking care of the kids while Kip works as a managing director of insurance. In her neighborhood, Erin says furniture, cars, engagement rings and well-manicured lawns are all signs of status. She says her neighborhood is a safe place for her kids to play outside and ride bikes unattended.

Carrie's boys (left) are not currently involved in any extracurricular activities because of the high costs, especially fees for sports. After school, the boys typically play video games, go play outside or enjoy a trip to the park. Carrie's boys attend the public school near their home where classes are oversized and a parking lot serves as the school playground. "For the boys' future, I hope that they do get the chance to go to college," says Carrie. "I would like them to be able to afford the things that they need and not to struggle the way I did."

Erin says a typical "crazy day" is jam-packed with sports and activities for all five children, from soccer practices to swimming classes. School is another top priority. Erin says she and her husband chose their neighborhood (right) for the quality of schools in the district. "College is expected for all of our children," says Erin. "We want all of them to have the best education they can and to be whoever they want to be."

Erin says a typical "crazy day" is jam-packed with sports and activities for all five children, from soccer practices to swimming classes. School is another top priority. Erin says she and her husband chose their neighborhood (right) for the quality of schools in the district. "College is expected for all of our children," says Erin. "We want all of them to have the best education they can and to be whoever they want to be."

Out of financial necessity, Carrie (left) says she's a big bargain shopper and can't get her kids everything they ask for. "Jerry and Caleb know that they don't just get something, that they have to earn it," says Carrie. "I feel that if you give them everything they want when they want it, that there is no learning of values."

Erin (right) says she likes to wear certain clothes and carry designer purses to fit into the upper class level. She says her kids are also touched by class—if they don't wear the right clothes, Erin says they simply won't fit in. "Our kids feel a sense of entitlement," says Erin, "If they're at the store and they want something, and I say 'No,' they say, 'Why not?'"

Carrie and Erin each have different methods for disciplining their children. "There's no talking back in our house, they know the rules and they know that that is unacceptable to us and disrespectful," says Carrie.

Erin says she wishes she could be a better disciplinarian with her kids. "I try to be strict, but unfortunately I fall back to negotiation," says Erin.

Erin (right) says she likes to wear certain clothes and carry designer purses to fit into the upper class level. She says her kids are also touched by class—if they don't wear the right clothes, Erin says they simply won't fit in. "Our kids feel a sense of entitlement," says Erin, "If they're at the store and they want something, and I say 'No,' they say, 'Why not?'"

Carrie and Erin each have different methods for disciplining their children. "There's no talking back in our house, they know the rules and they know that that is unacceptable to us and disrespectful," says Carrie.

Erin says she wishes she could be a better disciplinarian with her kids. "I try to be strict, but unfortunately I fall back to negotiation," says Erin.

Robert Reich, former Secretary of Labor for the Clinton Administration, is an expert on social policy and class in America. Robert says that a family's ability to provide their children with a quality education, health care and access to other resources determines one's class. "A lot of kids who are poor or working class are not getting the schools that they need and are not having the connections and the models of success that they need."

Robert says there are three common indicators of class: weight, teeth and dialect. In terms of appearance, people who are overweight or have poor teeth are generally regarded as lower class. The way someone talks says even more about their class. "People pay attention to dialect, to language," says Robert. "If you have the local dialect, wherever you're from, you're considered to be not as educated."

These class designators also lend themselves to their own kind of discrimination. "People speak different forms of English and there is prejudice," says Robert. "We have sexism in this country, we have racism, but we also have classism—and we are very sensitive to language."

Robert says there are three common indicators of class: weight, teeth and dialect. In terms of appearance, people who are overweight or have poor teeth are generally regarded as lower class. The way someone talks says even more about their class. "People pay attention to dialect, to language," says Robert. "If you have the local dialect, wherever you're from, you're considered to be not as educated."

These class designators also lend themselves to their own kind of discrimination. "People speak different forms of English and there is prejudice," says Robert. "We have sexism in this country, we have racism, but we also have classism—and we are very sensitive to language."

Though Robert calls the rags-to-riches story "a very important part of the American creed," he says the middle class is actually shrinking. He compares the range of incomes and classes in America to a ladder. "That ladder is getting longer and longer and longer," Robert says. "So even though people are working harder than they ever have in their lives, they are not making it today. ... The middle rungs on that ladder are not there any longer."

According to Robert, most people end up in the same class as their parents. "We live in a society in which the most important predictor in where you're going to end up—in terms of class and also wealth—is your parents' class and their wealth."

According to Robert, most people end up in the same class as their parents. "We live in a society in which the most important predictor in where you're going to end up—in terms of class and also wealth—is your parents' class and their wealth."

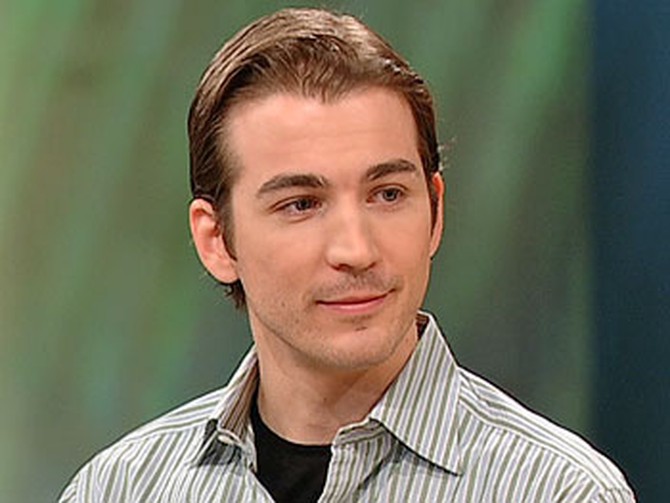

Through his documentary films, Jamie Johnson brings viewers inside the culture of megarich families and exposes how they think, act and spend. As an heir to the Johnson & Johnson pharmaceutical fortune, Jamie has access to this exclusive world that 99 percent of America would never see.

His first film, Born Rich, exposed how 10 children from wealthy families spent their time and their money. For his new film, The One Percent, Jamie turns the camera on his own family, breaking what he calls an "unspoken rule" of families with old money—he confronted them about their class, wealth and inheritance.

His first film, Born Rich, exposed how 10 children from wealthy families spent their time and their money. For his new film, The One Percent, Jamie turns the camera on his own family, breaking what he calls an "unspoken rule" of families with old money—he confronted them about their class, wealth and inheritance.

In addition to exposing the culture of super-rich families, in The One Percent Jamie also discusses what life is like on the other end of the economic spectrum. His film explains the widening gap between haves and have-nots in America.

According to The One Percent, since 1979...

Jamie says this rising inequality gap could be an ominous sign. "Historians always list a growing wealth gap among the many reasons for the decline of great civilizations," he says.

Robert Reich agrees. "Societies are fragile things, they're based on trust," he says. "If people don't feel that they have a fair chance of getting ahead...a lot of people feel excluded. That's not good for society. That doesn't keep America together."

According to The One Percent, since 1979...

- The top one percent of Americans own roughly 40 percent of the country's wealth.

- The top one percent possesses more wealth than the bottom 90 percent combined.

- An average member of the top one percent earns roughly $862,000 a year while a majority of Americans earn only $34,736. That's what the average CEO earns in less than one day of work!

Jamie says this rising inequality gap could be an ominous sign. "Historians always list a growing wealth gap among the many reasons for the decline of great civilizations," he says.

Robert Reich agrees. "Societies are fragile things, they're based on trust," he says. "If people don't feel that they have a fair chance of getting ahead...a lot of people feel excluded. That's not good for society. That doesn't keep America together."

By confronting rich families about their massive inherited wealth, Jamie admits he may have upset many people, including family members who could conceivably cut him out of the fortune. Would he be upset if that happened?

"I've had opportunities to have any educational opportunity I wanted. I've traveled all around the world. Money has never been a worry for me in my life. I'm aware to the degree that it's done wonderful things for me. It also has given me the great opportunity to pursue making films and that's really a great part of my life. I really love doing it. And I feel lucky to be in that position. So certainly, I feel like money has been a tremendous asset in my life in every way," he says. "My life would not be as good if I were cut out of the will."

"I've had opportunities to have any educational opportunity I wanted. I've traveled all around the world. Money has never been a worry for me in my life. I'm aware to the degree that it's done wonderful things for me. It also has given me the great opportunity to pursue making films and that's really a great part of my life. I really love doing it. And I feel lucky to be in that position. So certainly, I feel like money has been a tremendous asset in my life in every way," he says. "My life would not be as good if I were cut out of the will."

Nicole Buffett is the granddaughter of billionaire investor Warren Buffett—the second-richest man in the world. Warren is particularly known for a lifestyle that is far less flamboyant than his wealth could allow. Although he paid for her education, Nicole says she isn't counting on receiving any more money from her grandfather. "He would never want any of his children or grandchildren to be [born too wealthy]," Nicole says. "He thinks it would kind of rob of us our experience."

Nicole works as an artist and also earns money organizing the house of a wealthy family in San Francisco. "It's a very weird thing to be working for a very wealthy family considering I do come from one of the wealthiest families in America," Nicole says. "And I feel that the family I work for feels a bit of humor around the fact that I am from one of the wealthiest families—a wealthier family than, I believe, they are."

She recognizes that she lives between two classes—she is from a wealthy family but doesn't actually have that wealth. Does she wish she had more money? "I'm at peace with [not having inherited wealth]," she says, "but I do feel that it would be nice to be involved with creating things for others with that money and to be involved in it. I feel completely excluded from it."

Nicole works as an artist and also earns money organizing the house of a wealthy family in San Francisco. "It's a very weird thing to be working for a very wealthy family considering I do come from one of the wealthiest families in America," Nicole says. "And I feel that the family I work for feels a bit of humor around the fact that I am from one of the wealthiest families—a wealthier family than, I believe, they are."

She recognizes that she lives between two classes—she is from a wealthy family but doesn't actually have that wealth. Does she wish she had more money? "I'm at peace with [not having inherited wealth]," she says, "but I do feel that it would be nice to be involved with creating things for others with that money and to be involved in it. I feel completely excluded from it."

Published 04/21/2006