Behind the Headlines

Residents of Palmdale, California, have brought their families to the local baseball field for years. For the Rourke and Harris families, April 12, 2005, was a day that changed everything.

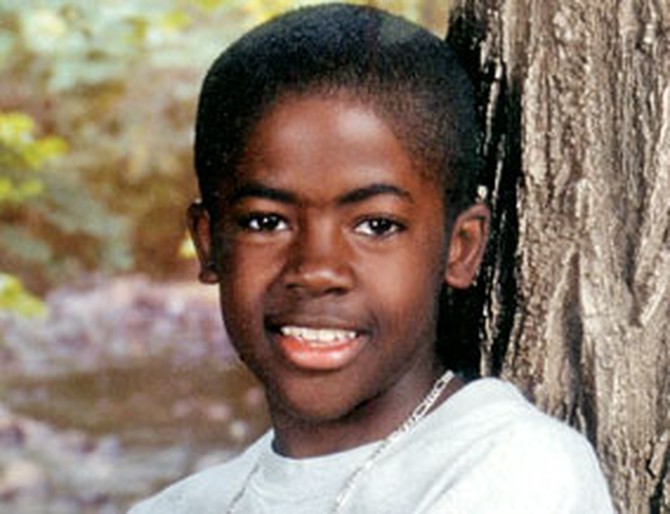

Thirteen-year-old Greg Harris Jr.—nicknamed Little Greg, or L.G.—pitched three innings that day. He was an honor student with a love for baseball, fishing, singing and dancing. Meanwhile, 15-year-old Jeremy Rourke and his father, Brian, sat in the stands watching the game. L.G.'s team ended up losing the game.

After the game, L.G. spoke briefly with his dad, Greg Sr., and then walked to the snack bar carrying his equipment bag. Jeremy was on his way to the snack bar too.

According to eyewitnesses, L.G. was standing in line at the snack bar when Jeremy approached and started to tease and push L.G. Moments later, L.G. pulled his bat from his bag and swung at Jeremy twice: hitting him first in the leg, and then in the head.

Jeremy was rushed to the emergency room and was pronounced dead two hours later. L.G.—who had no history of violence or criminal behavior—was taken into police custody and was later convicted of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to 12 years of confinement in a youth detention center.

In 2007, L.G.'s second-degree murder conviction was reduced to voluntary manslaughter.

Thirteen-year-old Greg Harris Jr.—nicknamed Little Greg, or L.G.—pitched three innings that day. He was an honor student with a love for baseball, fishing, singing and dancing. Meanwhile, 15-year-old Jeremy Rourke and his father, Brian, sat in the stands watching the game. L.G.'s team ended up losing the game.

After the game, L.G. spoke briefly with his dad, Greg Sr., and then walked to the snack bar carrying his equipment bag. Jeremy was on his way to the snack bar too.

According to eyewitnesses, L.G. was standing in line at the snack bar when Jeremy approached and started to tease and push L.G. Moments later, L.G. pulled his bat from his bag and swung at Jeremy twice: hitting him first in the leg, and then in the head.

Jeremy was rushed to the emergency room and was pronounced dead two hours later. L.G.—who had no history of violence or criminal behavior—was taken into police custody and was later convicted of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to 12 years of confinement in a youth detention center.

In 2007, L.G.'s second-degree murder conviction was reduced to voluntary manslaughter.

Gigi and Greg Sr., L.G.'s parents, think that while some punishment is appropriate, the 12-year sentence L.G. originally received for the second-degree murder conviction was too harsh.

"I want everyone to know our hearts do go out to the Rourkes, and we know that this was a mistake," Gigi says. "We know, and my son knows, this was an accident. He didn't intentionally go to that baseball field to harm Jeremy."

They say that the media portrayal of L.G. was never accurate. "He's not that monster that he's been portrayed as. He's a very kind-hearted person, a good kid," Gigi says.

They say that the reason L.G. pulled the bat out of his bag was that he was scared of Jeremy, who was older and bigger. The Harrises say Jeremy weighed 190 pounds and L.G. weighed 87 pounds. "I think it was more of a fear factor for him with the size difference, and it just escalated," Gigi says. "[The teasing] would not stop; it just kept going and going. And he didn't know how to get himself out of the situation ... because he hasn't been in a confrontation [like that]. He's well liked; he's a very confident kid."

"He was just scared," Greg Sr. says. "I think that's really what bothers us the most about [the second-degree murder] they [originally] charged him with."

"I want everyone to know our hearts do go out to the Rourkes, and we know that this was a mistake," Gigi says. "We know, and my son knows, this was an accident. He didn't intentionally go to that baseball field to harm Jeremy."

They say that the media portrayal of L.G. was never accurate. "He's not that monster that he's been portrayed as. He's a very kind-hearted person, a good kid," Gigi says.

They say that the reason L.G. pulled the bat out of his bag was that he was scared of Jeremy, who was older and bigger. The Harrises say Jeremy weighed 190 pounds and L.G. weighed 87 pounds. "I think it was more of a fear factor for him with the size difference, and it just escalated," Gigi says. "[The teasing] would not stop; it just kept going and going. And he didn't know how to get himself out of the situation ... because he hasn't been in a confrontation [like that]. He's well liked; he's a very confident kid."

"He was just scared," Greg Sr. says. "I think that's really what bothers us the most about [the second-degree murder] they [originally] charged him with."

Gigi and Greg Sr. visit L.G. every weekend at the detention center. They're worried about how much he'll change during his incarceration. "Hopefully he'll 'be L.G.' when he returns home," Gigi says. "He's mentoring other kids now [in the youth detention facility]. That's his personality, to help other kids stay out of trouble."

"Our hearts—my heart and my wife's—go out," Greg Sr. says. "When I visit my son, I always think about [Jeremy]. I think about [Jeremy's dad, Brian,] because I know, as a father, it hurts me just because my son is not home. I have to see him once a week. I can't put myself in his shoes, but I can imagine how he feels."

"Our hearts—my heart and my wife's—go out," Greg Sr. says. "When I visit my son, I always think about [Jeremy]. I think about [Jeremy's dad, Brian,] because I know, as a father, it hurts me just because my son is not home. I have to see him once a week. I can't put myself in his shoes, but I can imagine how he feels."

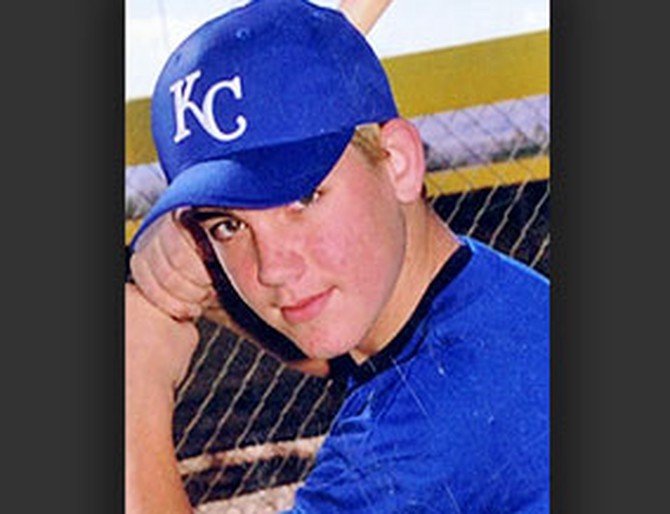

Jeremy's parents disagree with the Harrises about the fairness of L.G.'s original sentence. The Rourkes dispute the claims that Jeremy had been bullying or provoking L.G., or any other boy, before he was killed. The Rourkes also dismiss the idea that Jeremy was destructive or overly aggressive in some way.

In a vigil after the incident, the Rourkes made a statement in which they asked that L.G. not be vilified for Jeremy's death. They also stated that they preferred for L.G. to be tried as a juvenile and not as an adult, removing the chance that L.G. would be given a life sentence. "He was a good boy, and he made a bad mistake," says Angela, Jeremy's mother.

Jeremy's parents disagree with the Harrises about the fairness of L.G.'s original sentence. "If [L.G.] were tried as an adult," Brian, Jeremy's father, reasons, "he would have gotten 15 to life. And age-wise he was within, what, a few months of being at that age to be tried as an adult [according to California law]."

In a vigil after the incident, the Rourkes made a statement in which they asked that L.G. not be vilified for Jeremy's death. They also stated that they preferred for L.G. to be tried as a juvenile and not as an adult, removing the chance that L.G. would be given a life sentence. "He was a good boy, and he made a bad mistake," says Angela, Jeremy's mother.

Jeremy's parents disagree with the Harrises about the fairness of L.G.'s original sentence. "If [L.G.] were tried as an adult," Brian, Jeremy's father, reasons, "he would have gotten 15 to life. And age-wise he was within, what, a few months of being at that age to be tried as an adult [according to California law]."

Oprah: When somebody is killed tragically this way, the talk is always about the way he died. Since you have an audience of people around the world to listen to you, let's talk for a moment about the kind of life Jeremy lived.

Brian: I'll tell you, he lived life every day. He never missed a moment for Jeremy—that's actually the way he talked about himself, in third [person] all the time. He was always full of life all the time, no matter where he was. One thing we've actually learned from this is to live life a little fuller. You never know when something's going to happen.

Brian: I'll tell you, he lived life every day. He never missed a moment for Jeremy—that's actually the way he talked about himself, in third [person] all the time. He was always full of life all the time, no matter where he was. One thing we've actually learned from this is to live life a little fuller. You never know when something's going to happen.

Much like the Rourke and Harris families, Bruce has learned that it only takes a moment for your world to come crashing down.

For Bruce, the moment came on a beautiful fall day, minutes after finishing lunch with Cindy, his wife of 20 years, and Chelsea, their adopted daughter.

On his way out the door, he kissed Cindy and Chelsea goodbye and left for work. Before he got far, Bruce realized he had forgotten something at home and turned the car around. As he got closer to his neighborhood, he noticed a thick cloud of black smoke hovering on the horizon.

"I thought it was a house fire," Bruce says. "When I got to the intersection of our complex, I noticed smoke was coming from a car crash. Something came over me. I just had a feeling that this was not good."

When Bruce arrived on the scene, he saw his wife's minivan in flames.

"The last thing I remember was [the van] exploded," Bruce says. "I remember freaking out, and then, all of a sudden, I tried to gather my thoughts and started looking around to see if they were out of the vehicle. Within seconds, I realized there's no way anyone could survive that."

For Bruce, the moment came on a beautiful fall day, minutes after finishing lunch with Cindy, his wife of 20 years, and Chelsea, their adopted daughter.

On his way out the door, he kissed Cindy and Chelsea goodbye and left for work. Before he got far, Bruce realized he had forgotten something at home and turned the car around. As he got closer to his neighborhood, he noticed a thick cloud of black smoke hovering on the horizon.

"I thought it was a house fire," Bruce says. "When I got to the intersection of our complex, I noticed smoke was coming from a car crash. Something came over me. I just had a feeling that this was not good."

When Bruce arrived on the scene, he saw his wife's minivan in flames.

"The last thing I remember was [the van] exploded," Bruce says. "I remember freaking out, and then, all of a sudden, I tried to gather my thoughts and started looking around to see if they were out of the vehicle. Within seconds, I realized there's no way anyone could survive that."

What could have caused such a tragic accident? Bruce learned a few days later that Justin, the 19-year-old driver of the other car, was drag racing when he crashed into Cindy's minivan.

Justin says before the day he hit Cindy's car, he had never participated in any sort of drag race. He was a good student, had never gotten into trouble and had never even had a speeding ticket.

"[The race] started as an acceleration contest that went out of control," Justin recalls. "The last thing I remember is coming around the bend and seeing the minivan pulling out in front of me. Shortly after, I blanked out. When I came back, I could remember hearing sirens and seeing smoke everywhere. I could hear a man outside crying about his wife and daughter."

According to reports, Justin's car was traveling at speeds of 80 to 100 mph when the collision occurred.

Justin says before the day he hit Cindy's car, he had never participated in any sort of drag race. He was a good student, had never gotten into trouble and had never even had a speeding ticket.

"[The race] started as an acceleration contest that went out of control," Justin recalls. "The last thing I remember is coming around the bend and seeing the minivan pulling out in front of me. Shortly after, I blanked out. When I came back, I could remember hearing sirens and seeing smoke everywhere. I could hear a man outside crying about his wife and daughter."

According to reports, Justin's car was traveling at speeds of 80 to 100 mph when the collision occurred.

Bruce spent the next three years of his life on a mission to convict Justin of murdering his wife and daughter.

"I was outraged," Bruce says. "I was still numb from having lost my wife and my daughter, but I was very outraged. I thought, you know, [it was] over something so stupid and careless that two innocent people were killed."

During his quest for justice, Bruce quit his job, hired a private investigator and paid thousands of dollars to put Justin behind bars. Eventually, Bruce got what he wanted. He was in a Florida court, face-to-face with the person who had killed his family.

Justin was charged with two counts of vehicular homicide. He pled guilty to all charges and was awaiting sentencing when he received an unexpected request. Bruce wanted to meet Justin in person...without any lawyers.

"I was outraged," Bruce says. "I was still numb from having lost my wife and my daughter, but I was very outraged. I thought, you know, [it was] over something so stupid and careless that two innocent people were killed."

During his quest for justice, Bruce quit his job, hired a private investigator and paid thousands of dollars to put Justin behind bars. Eventually, Bruce got what he wanted. He was in a Florida court, face-to-face with the person who had killed his family.

Justin was charged with two counts of vehicular homicide. He pled guilty to all charges and was awaiting sentencing when he received an unexpected request. Bruce wanted to meet Justin in person...without any lawyers.

Bruce says that over time, his heart softened toward Justin, and he began to think of his two sons, who were around Justin's age. Bruce says he wanted to meet with Justin one-on-one to hear what Justin had to say from his heart.

"I thought, what good is it going to do putting this kid in prison for 30 years?" Bruce says. "Everyone's going to forget about him. Everyone's going to forget [about] Cindy and Chelsea. And I felt that there was a better way to handle this. I chose to, number one, forgive him for what he had done, but I also wanted to go further...I wanted to meet this young man and see what he had to say."

For the first eight minutes of the meeting, Justin says he was too emotional to speak. Then, Bruce handed him some tissues, and the words came pouring out. "I immediately asked for forgiveness," Justin says. "I told him I was sorry and that I never intended for any of this to happen."

Bruce spoke to his sons soon after the meeting, and they decided to make a plea agreement with Justin. Instead of the possible 30 years in prison, Justin was sentenced to eight years of probation, two years of house arrest, 300 hours of community service and a five-year license revocation.

Since then, Bruce and Justin have teamed up to speak at high schools about irrational driving. Justin has also changed the way he lives his life.

"[Bruce's] wife was a wonderful woman," Justin says. "I try to live my life by those standards that they lived their lives by, and in some small way, to make up for them not being here. I'm not saying I'm a saint, and I'm not saying that I can possibly ever live [up] to those standards. But I will try my best every day to."

"I thought, what good is it going to do putting this kid in prison for 30 years?" Bruce says. "Everyone's going to forget about him. Everyone's going to forget [about] Cindy and Chelsea. And I felt that there was a better way to handle this. I chose to, number one, forgive him for what he had done, but I also wanted to go further...I wanted to meet this young man and see what he had to say."

For the first eight minutes of the meeting, Justin says he was too emotional to speak. Then, Bruce handed him some tissues, and the words came pouring out. "I immediately asked for forgiveness," Justin says. "I told him I was sorry and that I never intended for any of this to happen."

Bruce spoke to his sons soon after the meeting, and they decided to make a plea agreement with Justin. Instead of the possible 30 years in prison, Justin was sentenced to eight years of probation, two years of house arrest, 300 hours of community service and a five-year license revocation.

Since then, Bruce and Justin have teamed up to speak at high schools about irrational driving. Justin has also changed the way he lives his life.

"[Bruce's] wife was a wonderful woman," Justin says. "I try to live my life by those standards that they lived their lives by, and in some small way, to make up for them not being here. I'm not saying I'm a saint, and I'm not saying that I can possibly ever live [up] to those standards. But I will try my best every day to."

There's a terrifying new trend sweeping the nation...and it's considered a "game" by many teens. Unlike reckless driving, teen violence and drug use, the choking game or "pass-out" game isn't illegal and is easily hidden from parents. But the consequences are just as deadly.

Using everything from shoelaces to belts to bike chains, kids cut off the oxygen flow to the brain, which creates a tingling sensation and causes a person to pass out. Children as young as 8 years old have started playing the choking game to get a quick high.

Usually, the unconscious state lasts only a few seconds...but some children never wake up. Dennis and Tricia, the parents of a thrill-seeking 16-year-old, first learned about the choking game in the summer of 2005. But the lesson came too late.

Using everything from shoelaces to belts to bike chains, kids cut off the oxygen flow to the brain, which creates a tingling sensation and causes a person to pass out. Children as young as 8 years old have started playing the choking game to get a quick high.

Usually, the unconscious state lasts only a few seconds...but some children never wake up. Dennis and Tricia, the parents of a thrill-seeking 16-year-old, first learned about the choking game in the summer of 2005. But the lesson came too late.

In August 2005, Dennis and Tricia's son Jeff died while playing the choking game.

"I worried most every day what he might get into or try," Tricia says. "[Jeff] was always taking things to the highest level you could push it. We were just always holding our breath."

Dennis and Tricia say they warned their kids about high-risk behaviors like underage drinking and drug abuse, but, like most parents, they weren't aware of this "modern-day Russian roulette."

"He wasn't drinking," Dennis says. "He wasn't driving fast. He wasn't doing any drugs. He wasn't doing any of the things that we always made sure our kids didn't do. ... In his mind, he wasn't doing anything that would violate or hurt us."

As Dennis thinks back over the summer, he remembers one subtle hint that Jeff was involved in something dangerous. He says the he saw Jeff wrapping a rope around his neck in the backyard one afternoon and asked his son what he was doing. Startled, Jeff gave his father a believable excuse, and Dennis let it slide.

"I worried most every day what he might get into or try," Tricia says. "[Jeff] was always taking things to the highest level you could push it. We were just always holding our breath."

Dennis and Tricia say they warned their kids about high-risk behaviors like underage drinking and drug abuse, but, like most parents, they weren't aware of this "modern-day Russian roulette."

"He wasn't drinking," Dennis says. "He wasn't driving fast. He wasn't doing any drugs. He wasn't doing any of the things that we always made sure our kids didn't do. ... In his mind, he wasn't doing anything that would violate or hurt us."

As Dennis thinks back over the summer, he remembers one subtle hint that Jeff was involved in something dangerous. He says the he saw Jeff wrapping a rope around his neck in the backyard one afternoon and asked his son what he was doing. Startled, Jeff gave his father a believable excuse, and Dennis let it slide.

Throughout the summer, Mike says he'd seen Jeff play the choking game many times, but was never tempted to try it himself. Greg, Mike's younger brother, also saw Jeff pass out on four occasions...and chose to play the "game."

"[Jeff] just made it sound like it was kind of fun," Greg says. "He said that, I don't know, like it tingled and stuff...like you were kind of high. And I was kind of curious how it felt, so I had done it."

Greg says he used a rope to play the "game" that cut off the oxygen to his brain.

To achieve the desired "high," Greg says you choke yourself until you're about to lose consciousness and then let go of the rope. The real danger comes when children try this game alone and accidentally pass out with the rope still around their necks.

Unlike Jeff, Greg didn't like the sensation the choking game gave him, and he says he'll never try it again.

According to experts, the choking game is most common among children ages 9 to 14. Find out more about the warning signs.

"[Jeff] just made it sound like it was kind of fun," Greg says. "He said that, I don't know, like it tingled and stuff...like you were kind of high. And I was kind of curious how it felt, so I had done it."

Greg says he used a rope to play the "game" that cut off the oxygen to his brain.

To achieve the desired "high," Greg says you choke yourself until you're about to lose consciousness and then let go of the rope. The real danger comes when children try this game alone and accidentally pass out with the rope still around their necks.

Unlike Jeff, Greg didn't like the sensation the choking game gave him, and he says he'll never try it again.

According to experts, the choking game is most common among children ages 9 to 14. Find out more about the warning signs.

Published 11/18/2005