AIDS Comes to a Small Town

In July 1987, the tiny town of Williamson, West Virginia—population 5,600—became part of the national discussion about AIDS. Mike Sisco, a man from Williamson who had tested positive for AIDS, took a dip in the local swimming pool. Word spread quickly, and by the next day fear, panic and rumors—including one that claimed Mike had spit on food at a grocery store—had forced the pool to be closed and prompted a front-page banner headline in the local newspaper.

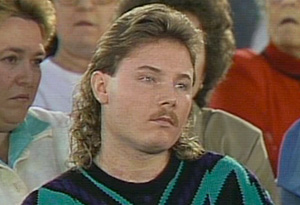

Watch Mike tell Oprah his story in his own words.

Mike says that when he went swimming at the Williamson pool, the lifeguard was the first person to recognize him, but soon the other bathers did as well. "They kind of ran like in those science fiction movies where Godzilla walks into the street."

This wasn't the first time the community had reacted negatively to seeing Mike in public. He says he returned to Williamson after contracting AIDS while living in Dallas. He says his illness quickly became known in the community through the whispers of small-town gossip.

Williamson residents were not alone in their incorrect fears that AIDS can spread through casual contact—through sweat or saliva, from kissing, in swimming pools and even on doorknobs.

Watch Mike tell Oprah his story in his own words.

Mike says that when he went swimming at the Williamson pool, the lifeguard was the first person to recognize him, but soon the other bathers did as well. "They kind of ran like in those science fiction movies where Godzilla walks into the street."

This wasn't the first time the community had reacted negatively to seeing Mike in public. He says he returned to Williamson after contracting AIDS while living in Dallas. He says his illness quickly became known in the community through the whispers of small-town gossip.

Williamson residents were not alone in their incorrect fears that AIDS can spread through casual contact—through sweat or saliva, from kissing, in swimming pools and even on doorknobs.

Mike says he has known he was gay since he was 14 years old but tried to fight it at first. "I started praying. I wanted God to change me," he says. "I dated girls and tried to hide it as best I could, and I think I did a pretty good job for a while."

When a job offer in Dallas arose, Mike says he knew it was time to leave home to get away from the homophobic harassment he experienced in Williamson. When he returned home after contracting AIDS, he says the negative reaction he received from his neighbors picked up right where it left off. "I was dying, and I thought they could overlook the fact that I am a homosexual and see that I needed some compassion and to be in my hometown," Mike says. "[I felt] anger at first because I couldn't understand why."

Even some of Mike's own relatives shunned him—a "No trespassing" sign was installed on an family member's lawn.

When a job offer in Dallas arose, Mike says he knew it was time to leave home to get away from the homophobic harassment he experienced in Williamson. When he returned home after contracting AIDS, he says the negative reaction he received from his neighbors picked up right where it left off. "I was dying, and I thought they could overlook the fact that I am a homosexual and see that I needed some compassion and to be in my hometown," Mike says. "[I felt] anger at first because I couldn't understand why."

Even some of Mike's own relatives shunned him—a "No trespassing" sign was installed on an family member's lawn.

After his return home, Mike wasn't the only person to feel the sting of rebuke by the people of Williamson. "This town has done every single one in my family wrong. They have shunned us. I have walked in grocery stores, and people have turned around and left because of this," Mike's sister Liz says. "Now he is one of God's children...just as we all are. And I think people here need to stop and think: 'What if he was yours? What would you do?'"

Read what happens when Oprah returns to Williamson in 2010 and talks to Mike's sisters.

Read what happens when Oprah returns to Williamson in 2010 and talks to Mike's sisters.

When given the opportunity to address Mike, some residents of Williamson are openly hostile.

"Mike had a choice," one man says. "He shirked his responsibility as a man. And when he did that, he gave up his choice."

"We have children. We don't want them contracting AIDS. When he publicly went in a swimming pool knowing he had AIDS, why did he do it? My child was there; a lot of other children were there," one woman says. "The doctors can say you can't get it this way, but what if they come back someday and say, 'We were wrong?' I don't know if you can or you can't [get AIDS from a swimming pool]. I just don't think he should have endangered the lives of the people that were there."

"Mike had a choice," one man says. "He shirked his responsibility as a man. And when he did that, he gave up his choice."

"We have children. We don't want them contracting AIDS. When he publicly went in a swimming pool knowing he had AIDS, why did he do it? My child was there; a lot of other children were there," one woman says. "The doctors can say you can't get it this way, but what if they come back someday and say, 'We were wrong?' I don't know if you can or you can't [get AIDS from a swimming pool]. I just don't think he should have endangered the lives of the people that were there."

Though it seems most of the town is against him, some residents offer their support.

"If the community knows that a person has the virus, then I feel they shouldn't shun him. They can speak to him, but they don't have to go and have sex with him and they don't have to drink after him or anything like that," one woman says. "They can speak to him and not shun him and put him in a closet like they did back in the old times."

"I really feel like there should be some type of center set up for the AIDS victims. A lot of the AIDS victims are out on the streets. It could be their choice if they would like to go to that center. They would have someone with the same problem that they could speak with, so they could go to the center if they would like to," another woman says. "He shouldn't be treated the way he's being treated. That's not fair."

"If the community knows that a person has the virus, then I feel they shouldn't shun him. They can speak to him, but they don't have to go and have sex with him and they don't have to drink after him or anything like that," one woman says. "They can speak to him and not shun him and put him in a closet like they did back in the old times."

"I really feel like there should be some type of center set up for the AIDS victims. A lot of the AIDS victims are out on the streets. It could be their choice if they would like to go to that center. They would have someone with the same problem that they could speak with, so they could go to the center if they would like to," another woman says. "He shouldn't be treated the way he's being treated. That's not fair."

The mayor of Williamson says closing the pool was his duty to the people of the town. "If there's just one chance in a million that somebody could catch that virus from a swimming pool, I think I did the right thing," he says. "I contacted the newspaper, which let everybody know an AIDS patient was in the pool. And I contacted the state health department, and of course they said I overreacted and that they felt the pool should be opened. However, in the meantime, everybody in the community knew that there was an AIDS patient in that pool, and they could use their own judgments if they want to go in or not."

Dr. Woodrow Myers, a public health official from Indiana, tries to separate fact from fiction about the spread of HIV and AIDS. "I understand that fear, and it's a fear that many communities across the United States have," he says. "It's very important that folks know the facts, and the facts are you get this disease in blood-to-blood contact, you get this disease through sexual contact, and a mother can give this disease to her child."

Watch as residents react to Dr. Myers.

Some want to know if it would be possible to contract AIDS through urine if Mike urinated in the pool. "Urine is a body fluid, and there have been small, small numbers of the AIDS virus found in urine. But that's not the way this disease is transmitted," Dr. Myers says. "We know for a fact that all of the cases that we have seen thus far have been transmitted in very definite ways. None of those ways have included touching a doorknob or being in the swimming pool or touching the AIDS patient him- or herself. That is not the way we have seen it transmitted."

See what happens when Oprah returns to Williamson 23 years later.

Watch as residents react to Dr. Myers.

Some want to know if it would be possible to contract AIDS through urine if Mike urinated in the pool. "Urine is a body fluid, and there have been small, small numbers of the AIDS virus found in urine. But that's not the way this disease is transmitted," Dr. Myers says. "We know for a fact that all of the cases that we have seen thus far have been transmitted in very definite ways. None of those ways have included touching a doorknob or being in the swimming pool or touching the AIDS patient him- or herself. That is not the way we have seen it transmitted."

See what happens when Oprah returns to Williamson 23 years later.