Why Reading Fiction Is More Important Than Ever

Liesl Schillinger curls up with a bold, beautiful new book by the author of The God of Small Things and finds a world of compassion and community.

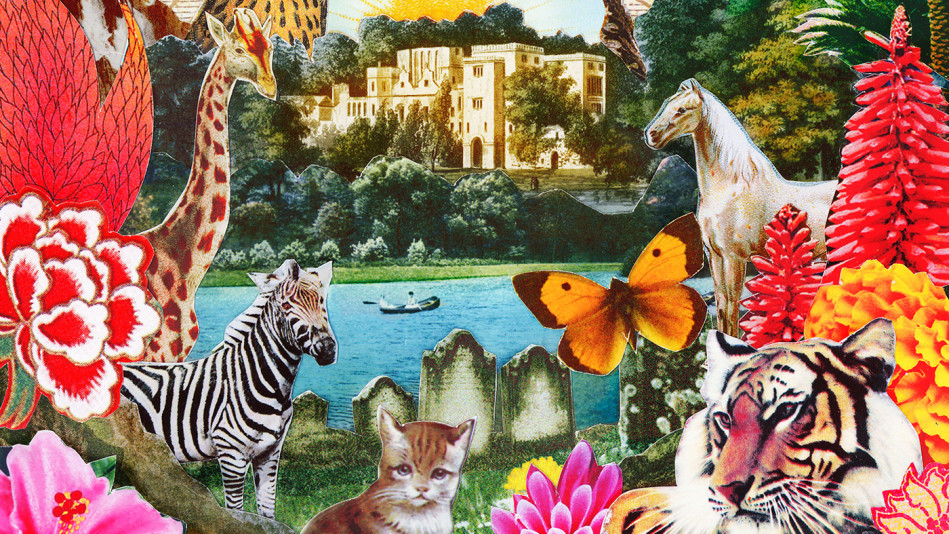

Illustration: Martin O'Neill

Early this year, days before Donald Trump's inauguration, President Obama met with The New York Times' chief book critic, Michiko Kakutani, at the White House to talk about why fiction matters. He told her: "When so much of our politics is trying to manage this clash of cultures brought about by globalization and technology and migration, the role of stories to unify—as opposed to divide, to engage rather than to marginalize—is more important than ever." Storytelling, Obama said, "brings people together to have the courage to take action on behalf of their lives."

Arundhati Roy's magisterial second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, (Knopf) works its empathetic magic upon a breathtakingly broad slate—India of the last half century—inviting us to stand in solidarity with a defiant, embattled group of characters who refuse to be stigmatized or cast aside. The engine of Roy's story is a hijra (India's so-called third gender) named Anjum. Seeking a place where she can live unharassed, Anjum creates a home for herself in an Old Delhi cemetery, sleeping between the resting places of her forebears. Over time, she adds a roof, a mortuary, a school, a pool, and even a zoo; her makeshift utopia comes to be called the Jannat Guest House; Jannat, in Urdu and Hindi, means "Paradise." Anjum's charisma draws a vibrant assemblage of outcasts to join her—hijras, Kashmiri freedom fighters, activists, orphans, and low-caste Hindus and Muslims, not to mention a host of horses, dogs, cats, and birds. "People...carry their tragic histories and their misfortunes around like trophies," Roy writes. Over the course of the book's 12 chapters, the stories behind these "trophies" are brought to life, but at Anjum's graveyard paradise, the formerly unwanted get to set aside those painful tokens and embrace one another's unburdened selves. The Guest House is a place where they can "repudiate the world they lived in and call forth another one, just as real."

More than a century ago, E.M. Forster implored readers of his novel Howards End to "only connect," urging them to "live in fragments no longer." What Forster couldn't know was what neuroscientists and social psychologists have since discovered: that when we become engrossed in a work of fiction, we don't just read—we rewrite our brain's neural map. We enfold the characters' experiences into our own. We increase our powers of empathy. We connect so deeply that we emerge from the experience as new people, more fully human, more sublimely whole.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy (Knopf).

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy (Knopf).

Keep Reading: O's Top 20 Books to Read This Summer

Arundhati Roy's magisterial second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, (Knopf) works its empathetic magic upon a breathtakingly broad slate—India of the last half century—inviting us to stand in solidarity with a defiant, embattled group of characters who refuse to be stigmatized or cast aside. The engine of Roy's story is a hijra (India's so-called third gender) named Anjum. Seeking a place where she can live unharassed, Anjum creates a home for herself in an Old Delhi cemetery, sleeping between the resting places of her forebears. Over time, she adds a roof, a mortuary, a school, a pool, and even a zoo; her makeshift utopia comes to be called the Jannat Guest House; Jannat, in Urdu and Hindi, means "Paradise." Anjum's charisma draws a vibrant assemblage of outcasts to join her—hijras, Kashmiri freedom fighters, activists, orphans, and low-caste Hindus and Muslims, not to mention a host of horses, dogs, cats, and birds. "People...carry their tragic histories and their misfortunes around like trophies," Roy writes. Over the course of the book's 12 chapters, the stories behind these "trophies" are brought to life, but at Anjum's graveyard paradise, the formerly unwanted get to set aside those painful tokens and embrace one another's unburdened selves. The Guest House is a place where they can "repudiate the world they lived in and call forth another one, just as real."

More than a century ago, E.M. Forster implored readers of his novel Howards End to "only connect," urging them to "live in fragments no longer." What Forster couldn't know was what neuroscientists and social psychologists have since discovered: that when we become engrossed in a work of fiction, we don't just read—we rewrite our brain's neural map. We enfold the characters' experiences into our own. We increase our powers of empathy. We connect so deeply that we emerge from the experience as new people, more fully human, more sublimely whole.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy (Knopf).

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy (Knopf).

Keep Reading: O's Top 20 Books to Read This Summer