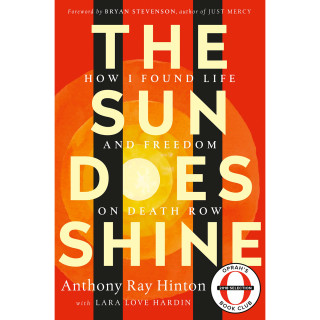

Deliverance: Oprah Talks to The Sun Does Shine Author Anthony Ray Hinton

For nearly 30 years, Ray Hinton's home was death row, where he desperately hoped the courts would finally acknowledge his innocence. Now he's free, and his memoir, The Sun Does Shine, is the new Oprah's Book Club pick.

Photo: Kwaku Alston

I was in Alabama interviewing social-justice warrior Bryan Stevenson and noticed a book on his desk. As I was leaving, he gave it to me. And for the next two days I was glued to Ray Hinton's soul-searing memoir. It will stay with me forever. As Stevenson—who personally took up Hinton's case 12 years into his sentence and finally got him released from prison after he'd served 28 years for two murders he didn't commit—puts it, the tale is "a textbook example of injustice." I was honored, a few weeks after I finished reading, to sit down with Ray and find out more about what he went through and how, remarkably, he kept the faith.

OPRAH: Ray, I've been listening to people's stories for a long time, but yours is about the most incredible. You spent almost three decades in prison for crimes you were not guilty of. Take us back to your arrest, when you were 29.

RAY HINTON: I was cutting the grass in the back of the house where I lived with my mother, in Burnwell, Alabama. After a few minutes, I looked up and there were two white gentlemen standing there. One asked, "Are you Anthony Ray Hinton?" I said I was. They said they were detectives and had a warrant for my arrest. When I asked what for, they wouldn't say. They handcuffed me and put me into the squad car.

OW: Your mom was still inside?

RH: I begged them to let me tell her what was happening. They took me into the house in handcuffs. Mama screamed and hollered and told them I hadn't done anything, but it didn't matter. It wasn't until later that they said the charges were first-degree robbery, kidnapping, and attempted murder.

OW: What did you say?

RH: I said I hadn't done any of that. But they told me that because there would be a white prosecutor, judge, and jury, they'd make sure I'd be found guilty.

OW: How did you respond?

RH: I asked the detective when this crime took place. When he told me, I said, "Thank you, Jesus." I was at work at that time, and my supervisor—who was white—could confirm that. I gave the detective his number.

OW: So you figured your boss would clear up the misunderstanding and the police would realize they had the wrong man.

RH: Yes. The detective left the room. When he got back, he said: "The good news is, your alibi checks out. The bad news is, we're going to charge you with capital murder."

OW: Now, your mother was one of those strong, black, Southern women who believed in authority, that the police were there to help.

RH: Yes, and that's what I believed.

OW: So then they go back to your mother's house and take her gun, which hadn't been fired in 25 years, and claim the bullets matched those found at the crime scene.

RH: They dusted it off and polished it up and lied—they actually lied.

OW: And after you were charged, you never even got to go home. They held you for 13 months before you went to trial. And the trial was a fiasco—they'd already decided.

RH: When I was indicted and the judge read the charges and asked if I could afford an attorney, I said no, so he appointed one. That attorney didn't even ask me my name. He told me he hadn't gone to law school to do pro bono work. I asked, "Would it make a difference if I told you I was innocent?" He said, "The problem with that statement is that all of y'all is always doing something, and then saying you didn't do it."

OW: Take us to the courtroom after a year has passed, and the ballistics expert your lawyer hired—missing an eye and no expert—has messed up badly. At that point did you think, I'm done for?

RH: Until that moment I thought justice would prevail. When I realized it wouldn't, it just sucked everything out of me. But I wanted to protect my mama. I didn't know if she understood that conviction meant the death penalty.

OW: You were immediately put on death row, where you had some very dark nights of the soul. You literally stopped speaking.

RH: I didn't speak for the first three years. The guards thought I couldn't talk. It was as if God had taken out my vocal cords.

OW: But three years in, you heard the man in the next cell crying—wailing and wailing.

RH: He'd lost his mother. I'd lived next to him and never even known his name. I wasn't there to make friends. But I thought of his mother and my mother, and how from an early age mine had taught me compassion. So I hollered through the wall: "Is something wrong over there?" At first he didn't answer. Then he told me his mom had passed. I said I was sorry. I told a corny joke, and we laughed a little bit. The next morning I realized my voice was back, and my sense of humor, too.

OW: On that night you realized you weren't the only man on death row.

RH: I realized we were both still human, and it's human nature to reach out.

OW: All that time, you knew you were innocent. Did you have to let that go?

RH: Yes. That, and my life as it was. Gone. To stay sane I lived in my head, where I could travel and imagine. In my mind, I played a championship game with the Knicks. I won Wimbledon five times. If the Yankees needed a home run, I came to bat.

OW: But you also started getting to know the other prisoners, like Henry.

RH: Henry was KKK. His father was a Klan leader who'd gotten upset that a black man hadn't been convicted of killing a white man, and ordered his son and other Klansmen to kill the first black man they came across. They hanged that poor kid.

OW: Henry was convicted of that crime— and would become the first white man to be executed for a lynching in 84 years.

RH: Yes. I didn't know that's who he was at first. We were just talking.

OW: Nobody can see each other on the row, so you know one another only by voices.

RH: Yes. Henry had been taught to hate all his life. He didn't know any different. Me and some of the other blacks there didn't judge him, since everyone on death row was accused of killing somebody. We became friends.

OW: Knowing what he'd done, you could still be friends?

RH: I was there for something I didn't do. I didn't know whether he'd done it or not.

OW: You never asked him?

RH: That was between him and his God.

OW: But he eventually admitted he'd been raised a racist.

RH: Death row was the only place where I never witnessed racism. We all went to bed with a death sentence on our heads and woke up that way. We had to become each other's support system.

OW: So much so that you created a book club! I'm very proud of my book club.

RH: I'm proud of mine!

OW: What gave you the idea?

RH: I felt society had let the men down. Most of the guys I was in with had dropped out of school in seventh or eighth grade. I knew books would open their minds. I convinced the warden to let me do it. For the first I chose Go Tell It on the Mountain.

OW: So you had the KKK reading James Baldwin.

RH: We also read To Kill a Mockingbird, and I thought, Tom is me!

OW: You put it this way in your book: "We were all slowly dying from our own fear—our minds killing us quicker than the State of Alabama ever could. Men would do all kinds of crazy things rather than spend another night with their own thoughts. Bring in the books, I thought. Let every man on the row have a week away, inside the world of a book. I knew if the mind could open, the heart would follow." Is that what happened to Henry?

RH: On the night of an execution, they ask you two things: What do you want for your last meal, and do you have anything you want to say? I was told Henry said, "All my life, everyone told me to hate. The people I was taught to hate taught me to love. As I leave this world, I leave knowing what love feels like."

OW: Death row taught Henry to love. What did it teach you?

RH: It taught me that either you love or you hate—you help or you harm. The men on death row had been told the world would be better without them. I tried to say that this may not be where we want to be, but let's do what we can for one another.

OW: Your mother didn't get to see you free.

RH: On September 22, 2002, my mama, Buhlar Hinton, died. When the guards told me, I gave up. She'd been deteriorating for a long time—I believe she died of a broken heart. I told Mr. Stevenson to forget about my case. But I also heard Mama saying, "I didn't bring you up to be a quitter. I want you to fight." She was always my biggest cheerleader. When I would strike out at a baseball game, she was there to say I'd hit it the next time, to tell me how good I was. But now I heard her telling me she was disappointed in me.

OW: Because you were thinking about killing yourself.

RH: Yes. The next morning I apologized to Mr. Stevenson and said I wanted him to give Alabama all the hell he could.

OW: By that time, Bryan Stevenson had already been on your case for years—and they still wouldn't reopen it.

RH: Mr. Stevenson said the Alabama judges would never do the right thing and that he needed to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. But he said, "Ray, if they rule against you, you'll be executed within two years." I was tired of sitting in that cage. I told him to file.

OW: Mr. Stevenson wanted the Supreme Court to review your case. They ended up vacating your conviction. Then local prosecutors dropped the charges. You were going to be free. What did that feel like?

RH: I cried like a baby. Then I asked when I'd get out. I got out 13 months later, on April 3, 2015—Good Friday. I hadn't been to a regular church in 30 years, but that Sunday I went to an Easter service.

OW: At one point there'd been a lawyer who offered you the opportunity to accept a sentence of life without parole, but you didn't take him up on it.

RH: Life without parole is for guilty people. When I was 12, my mother told me, "If you're man enough to bend down and pick up a rock, and if you're man enough to throw that rock, be man enough to admit you threw the rock." But this rock I hadn't thrown, so I couldn't say I had.

OW: On the day you were released, your best friend, Lester—who had visited you every single week for nearly 30 years—picked you up. You'd been behind bars since 1985. So you got in his car, and what was the first thing you wanted to do?

RH: Lester thought I'd want to get something decent to eat. But I wanted to go where they laid my mother's body. I see him messing with the radio dial, then we start driving down the road. I heard this little white lady say, "In one-tenth of a mile, turn right." I jumped and said, "What the hell?!"

OW: You thought there was a white lady in the car?

RH: Yes, and Lester's laughing so hard he has to pull over. He says, "That's a GPS!" When he explained what it does, it really hit me how long I'd been locked up. The world had changed.

OW: You've never gotten an apology from the state of Alabama. Would it mean something if you did?

RH: Yes. The victims' families still think I'm the person who killed their loved ones. I want them to have proof of who did do it. If the state said they're sorry, it won't give me back what I lost, but it would mean a lot to hear them say, We made a mistake; we won't do this again to someone else.

OW: Do you spend a lot of time thinking about what you lost?

RH: Sometimes, especially when I think about the years I lost with my mother. I wish I could have been there to give her some cold water when she was sick, or make her some soup and feed it to her, like she would've done for me. I didn't get to say goodbye.

OW: Do you feel her presence with you?

RH: Sometimes I can hear her saying, "I'm proud of you." Whenever I used to get an A or something, she was always there to bake me a nice peach cobbler or blackberry pie. I don't have anyone to do that for me.

OW: I feel like she's still guiding you, Ray. You're a good man.

More About Oprah's Book Club

Order your copy of The Sun Does Shine online or pick it up at your local bookstore or library. Visit Oprah.com/BookClub to learn more about the book.

Oprah and Anthony Ray Hinton on Oprah's Super Soul Conversations

Tune in to a televised special featuring a conversation between Oprah and Anthony Ray Hinton on Sunday, June 10, at 11 a.m. PT/ET on OWN. Plus, listen to the conversation on Oprah's podcast, Oprah's Super Soul Conversations. Part 1 will be available Monday, June 11, and Part 2 will be available Wednesday, June 13. You can find both on Apple Podcasts.