2 New Books Reveal Another Side of Langston Hughes

Celebrated actress and playwright Anna Deavere Smith contemplates the genius and humanity of the famous author.

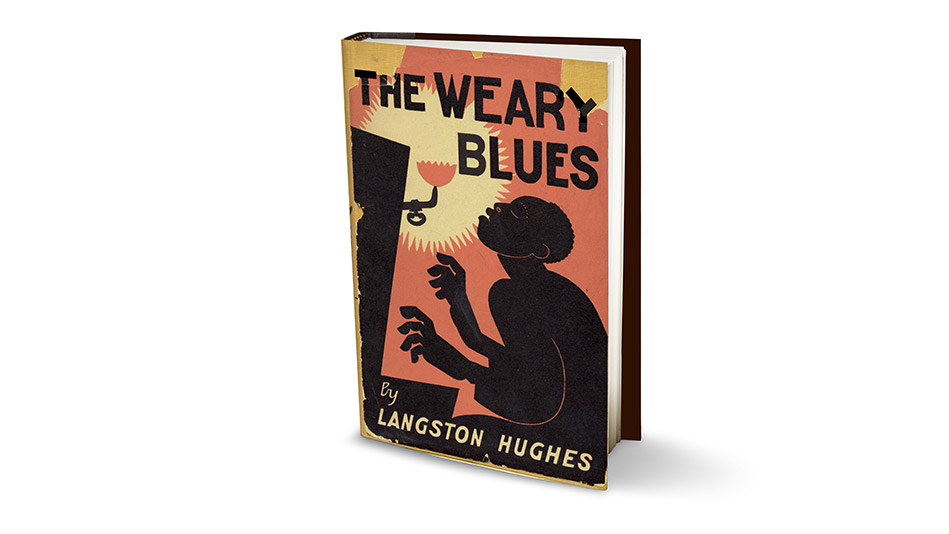

For nearly a century Langston Hughes has been essential reading. His poems, novels, essays and plays were at the forefront of the Harlem Renaissance and of modernism itself, and today are fundamentals of American culture. Now his 1926 book of poems, The Weary Blues, has been rereleased "in all its black, blues and symphonic glory," as poet Kevin Young puts it in the foreword for the new Knopf edition. Even more exciting: A collection of Hughes's letters—a volume every bit as revelatory as any memoir—is being published for the first time.

Hughes saved everything, and so the editors of Selected Letters of Langston Hughes (also from Knopf) had their work cut out for them. The letters start in the 1920s and cover every decade of Hughes's adult life up to his death in 1967, revealing him to be a compassionate and engaged man who possessed extraordinary talent, curiosity, and access to the literary and art worlds of his time.

I fell in love with Hughes early in the book when I read a letter he wrote to Alain Locke, the first African American Rhodes scholar, which he composed in 1923 while working as a messboy on a ship docked at Jones Point, New York. Even as a young man he wasn't content to be merely an intellectual—he was searching for more: "I'm stupid and only a young kid fascinated by his first glimpse of life, but then after so many years in a book-world and so much striving to be a 'bright boy' and an 'intelligent young man' it's rather nice to come here and be simple and stupid and to touch a life that is at least a living thing with no touch of books."

Hughes's graciousness and wit are evident throughout. James Baldwin once negatively reviewed a book of his poetry, writing, "Every time I read Langston Hughes I am amazed all over again by his genuine gifts—and depressed that he has done so little with them," an appraisal that must have cut Hughes deeply. Yet in a letter to Baldwin written two short years later, Hughes teases and then compliments him on his new essays: "Jimmy, I fear you are becoming a 'NEGRO' writer—and a propaganda one, at that! What's happening????? ... Anyhow, Nobody Knows My Name is fascinating reading, wonderful for many evenings of discussion for the talkative uptown and down—and surely makes of (you a) sage—a cullud sage—whose hair, once processed, seems to be reverting."

Serendipitously, just before reading the letters, I saw Bert Williams Lime Kiln Field Day Project at New York City's Museum of Modern Art. The recently restored film footage, originally shot in 1913, features a predominantly black cast supported by a white crew; it had never been shown before. Seeing what these actors and filmmakers were able to do together at a very segregated time in America took my breath away. Likewise, as I read Hughes's letters and reread his poetry, I marveled at the breadth and depth of his world view and at the opportunities he had—and embraced—to collaborate with whites. I wonder whether those of us who picked up where Hughes left off have done nearly as much. It's humbling and inspiring to think about, as are these reminders of Hughes's vision, and of his heart.