Getting to Know Gabriel García Márquez

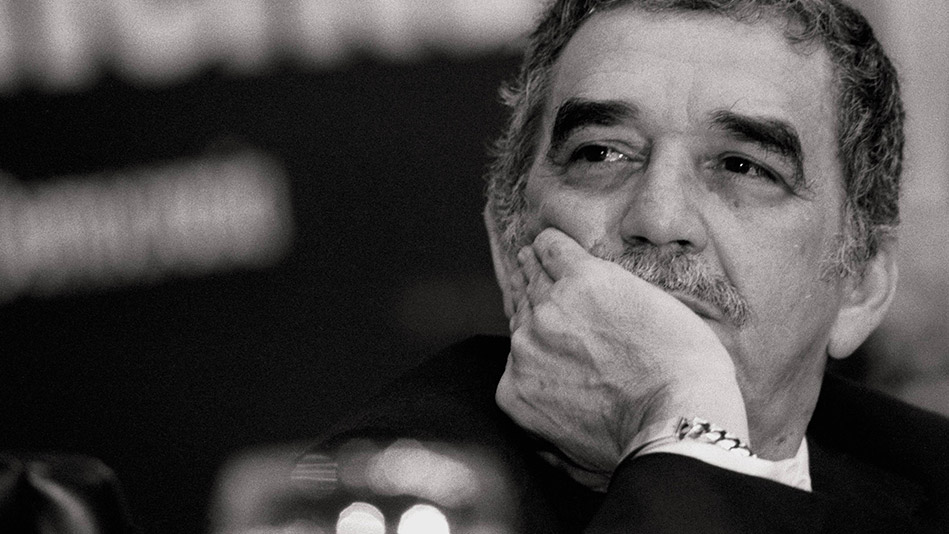

Photo: Paco Junquera/Cover/Getty Images

We were saddened to learn of the passing of one of the greatest writers of our time (whose novels One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera were both selected for Oprah's Book Club). Here we remember him in an interview with scholar Gene Bell-Villada in Mexico City June of 1982.

The following chat with García Márquez took place in his home on Calle Fuego, in the Pedregal section of Mexico City. It was June 1982. His wife, Mercedes—as beautiful and as warmly engaging as rumors say—had opened the front door for me, smiled, and then pointed me toward the inside driveway. "There he is," she said. "There's García Márquez."

Curly-haired and compact (about 5'6"), García Márquez emerged from [his] car wearing blue one-piece overalls with a front zipper—his morning writing gear, as it turns out. At this point their son Gonzalo, a very Mexican twenty-year-old, showed up with a shy, taciturn girlfriend. The in-family banter grew lively. In contrast to Gonzalo's Mexican-inflected speech, the novelist's soft voice and dropped s's immediately recalled to me the Caribbean accent of the northern Colombian coast where he had been born and raised.

García Márquez and Gonzalo soon led me across the backyard to the novelist's office, a separate bungalow equipped with special acclimatization (the author still could not take the morning chill in Mexico City), thousands of stereo LPs, various encyclopedias and other reference books, paintings by Latin American artists, and, on the coffee table, a Rubik's Cube. The remaining furnishings included a simple desk and chair and a matched sofa and armchair set, where our interview was held over beers.

Global fame notwithstanding—García Márquez remains a gentle and unassuming, indeed an admirably balanced and normal sort of man. Throughout our conversation I found it easy to imagine him in the downtown café, sipping drinks with the TV repairman or trading stories with the taco makers. He loves to chat; were it not for the cautious screening process set up by his friends and family, he could easily spend his entire day talking instead of writing.

Gene Bell-Villada: Your One Hundred Years of Solitude is required reading in many history and political science courses in the United States. There's a sense that it's the best general introduction to Latin America. How do you feel about that?

Gabriel García Márquez: I wasn't aware of that fact in particular, but I've had some interesting experiences along the way. On one occasion, a sociologist from Austin, Texas came to see me because he'd grown dissatisfied with his methods. So he asked me what my own method was. I told him I didn't have a method. All I do is read a lot, think a lot, and rewrite constantly. It's not a scientific thing.

GB-V: There's a very famous strike scene in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Was it much trouble for you to get it right?

GGM: That sequence sticks closely to the facts of the United Fruit strike of 1928, which dates from my childhood; I was born that year. The only exaggeration is in the number of the dead, although it does fit the proportions of the novel. So, instead of hundreds of dead, I upped it to thousands. But it's strange, a Colombian journalist the other day referred in passing to "the thousands who died in the 1928 strike." As my Patriarch says, it doesn't matter if it's true, because with enough time it will be!

GB-V: Some critics take you to task for not furnishing a more positive vision of Latin America. How do you answer them?

GGM: Yes, that happened to me in Cuba a while ago, where some critics gave One Hundred Years of Solitude high praise and then found fault with it for not offering a solution. I told them it's not the job of novels to furnish solutions.

GB-V: You're a writer with a very intimate knowledge of street life and plebeian ways. What do you owe it to?

GGM: [He reflects for a moment] It's in my origins; it's my vocation too. It's the life I know best, and I've deliberately cultivated it.

GB-V: With fame, is it hard, keeping up with your popular roots?

GGM: It's tough, but not as much as you'd think. I can go to a local café and at most one person will request an autograph. What's nice is that they treat me like one of their own, especially in hotels up in the States, where they feel good just meeting a Latin American. I never lose sight of the fact that I owe those experiences to the many readers of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

GB-V: And which of your books is your favorite?

GGM: It's always the latest, so right now it's Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Of course, there are always differences with readers, and every book is a process. I'm particularly fond of No One Writes to the Colonel, but then that book led me to One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Excerpted from Gene Bell-Villada's, casebook on the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.

The following chat with García Márquez took place in his home on Calle Fuego, in the Pedregal section of Mexico City. It was June 1982. His wife, Mercedes—as beautiful and as warmly engaging as rumors say—had opened the front door for me, smiled, and then pointed me toward the inside driveway. "There he is," she said. "There's García Márquez."

Curly-haired and compact (about 5'6"), García Márquez emerged from [his] car wearing blue one-piece overalls with a front zipper—his morning writing gear, as it turns out. At this point their son Gonzalo, a very Mexican twenty-year-old, showed up with a shy, taciturn girlfriend. The in-family banter grew lively. In contrast to Gonzalo's Mexican-inflected speech, the novelist's soft voice and dropped s's immediately recalled to me the Caribbean accent of the northern Colombian coast where he had been born and raised.

García Márquez and Gonzalo soon led me across the backyard to the novelist's office, a separate bungalow equipped with special acclimatization (the author still could not take the morning chill in Mexico City), thousands of stereo LPs, various encyclopedias and other reference books, paintings by Latin American artists, and, on the coffee table, a Rubik's Cube. The remaining furnishings included a simple desk and chair and a matched sofa and armchair set, where our interview was held over beers.

Global fame notwithstanding—García Márquez remains a gentle and unassuming, indeed an admirably balanced and normal sort of man. Throughout our conversation I found it easy to imagine him in the downtown café, sipping drinks with the TV repairman or trading stories with the taco makers. He loves to chat; were it not for the cautious screening process set up by his friends and family, he could easily spend his entire day talking instead of writing.

The Conversation

Gene Bell-Villada: Your One Hundred Years of Solitude is required reading in many history and political science courses in the United States. There's a sense that it's the best general introduction to Latin America. How do you feel about that?

Gabriel García Márquez: I wasn't aware of that fact in particular, but I've had some interesting experiences along the way. On one occasion, a sociologist from Austin, Texas came to see me because he'd grown dissatisfied with his methods. So he asked me what my own method was. I told him I didn't have a method. All I do is read a lot, think a lot, and rewrite constantly. It's not a scientific thing.

GB-V: There's a very famous strike scene in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Was it much trouble for you to get it right?

GGM: That sequence sticks closely to the facts of the United Fruit strike of 1928, which dates from my childhood; I was born that year. The only exaggeration is in the number of the dead, although it does fit the proportions of the novel. So, instead of hundreds of dead, I upped it to thousands. But it's strange, a Colombian journalist the other day referred in passing to "the thousands who died in the 1928 strike." As my Patriarch says, it doesn't matter if it's true, because with enough time it will be!

GB-V: Some critics take you to task for not furnishing a more positive vision of Latin America. How do you answer them?

GGM: Yes, that happened to me in Cuba a while ago, where some critics gave One Hundred Years of Solitude high praise and then found fault with it for not offering a solution. I told them it's not the job of novels to furnish solutions.

GB-V: You're a writer with a very intimate knowledge of street life and plebeian ways. What do you owe it to?

GGM: [He reflects for a moment] It's in my origins; it's my vocation too. It's the life I know best, and I've deliberately cultivated it.

GB-V: With fame, is it hard, keeping up with your popular roots?

GGM: It's tough, but not as much as you'd think. I can go to a local café and at most one person will request an autograph. What's nice is that they treat me like one of their own, especially in hotels up in the States, where they feel good just meeting a Latin American. I never lose sight of the fact that I owe those experiences to the many readers of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

GB-V: And which of your books is your favorite?

GGM: It's always the latest, so right now it's Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Of course, there are always differences with readers, and every book is a process. I'm particularly fond of No One Writes to the Colonel, but then that book led me to One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Excerpted from Gene Bell-Villada's, casebook on the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Photo: Alejandra Vega/AFP/Getty Images

Getting to Know Gabo

He's known throughout Latin America, with great fondness, as "Gabo." The people of his native country of Colombia, South America and his adopted hometown of Mexico City, Mexico regard him with love and reverence. They all claim him as one of their own. He's influenced writers and readers worldwide as a Nobel Prize winning author. He is a journalist, a mentor to journalists, a movie and television scriptwriter, a movie critic and a passionate advocate for his brand of politics. He speaks his mind and refuses to write or speak in anything but Spanish. Throughout the world, he is larger than life.

He is Gabriel García Márquez.

In the Beginning

Gabriel, nicknamed "Gabito" ("little Gabriel" after his father,) was born in March of 1927 in the tiny Colombian banana town of Aracataca. At the time of his birth, bananas were booming. The next year, the banana economy began to unravel and created a rift in the town that has never been repaired. Because his parents were struggling to make ends meet, he was taken in by his maternal grandparents and raised as a part of their family. They were colorful people; his grandfather was an old decorated Colonel and revered by the town and his grandmother, who sold candy animals to support the family, could deliver even the most outrageous, superstitious tale with conviction. They were both great storytellers and the house where they raised "Gabo" was haunted by ghosts. Such is the stuff of the life—and the art—of Gabriel García Márquez.

The Hungry Bohemian

At the age of 19, despite a passion to be a writer, García Márquez enrolled in the law program at the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, respecting his parents' desire for him to be "practical." Hungry for something to keep him engaged, Gabriel began wandering around Bogotá reading poetry instead of preparing for his law classes. He found genius in the works of Franz Kafka, William Faulkner (the most widely translated American writer of his generation,) Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. He began writing. His first novella, Leaf Storm, was rejected for publication in 1952 but later found a publisher in a fly-by-night operation, the CEO of which disappeared shortly thereafter.

The Lover

Before leaving his hometown for school at age eighteen, García Márquez met the 13-year-old Mercedes Barcha Pardo and pronounced her the most interesting woman he had ever met. He proposed to her in a fit of passion. At thirteen, she knew she wanted to finish school; she put off the engagement. Though they would not marry for another fourteen years, their love has lasted a lifetime and their marriage is a driving force for García Márquez. She is his muse, his champion. She was as sure of him as he was of her. While he traveled and found himself after dropping out of law school, she waited patiently for him in Colombia until he returned for her when she was 27-years-old.

The Exile

García Márquez transitioned to journalism after leaving school. He published a sensational but controversial piece about a shipwrecked sailor in Colombia. Worried he might be persecuted the government for his part in the scandalous piece, his editors sent him to Italy. In Europe, García Márquez' friends and editors kept him "moving" to keep him out of political trouble. In the course of five years he covered stories in Rome, Geneva, Poland, Hungary, Paris, Venezuela, Havana and New York City.

He continued to publish stories he believed in, but they made him an exile in his native Colombia and elsewhere. Because of the controversial nature of his political writings, he was not welcome in his own country in 1980. On a highly restricted visa, he was also denied entrance to the U.S.A. from 1962-1996—more than three decades. He was considered by many to be a renegade and a rebel—and he's never apologized.

Smoking, Scribbling and Success

After a three-year writers' block that lasted until the beginning of 1965, the personal novel he'd always hoped to write came pouring out of García Márquez. Within a week of the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967, all 8000 copies of the original printing had been sold.

It was translated into three-dozen languages and won the Chianchiano Prize in Italy, the Best Foreign Book in France, the Rómulo Gallegos Prize and ultimately the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Throughout this success, Gabo kept writing and smoking. He consumed sometimes six packs of cigarettes a day during the furious period of writing One Hundred Years of Solitude. His novels since, both magical and legendary, have kept him at the forefront of literature since 1970: The Autumn of the Patriarch, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Love in the Time of Cholera, The General in His Labyrinth, Of Love and Other Demons and his aptly named autobiography, Living to Tell the Tale.