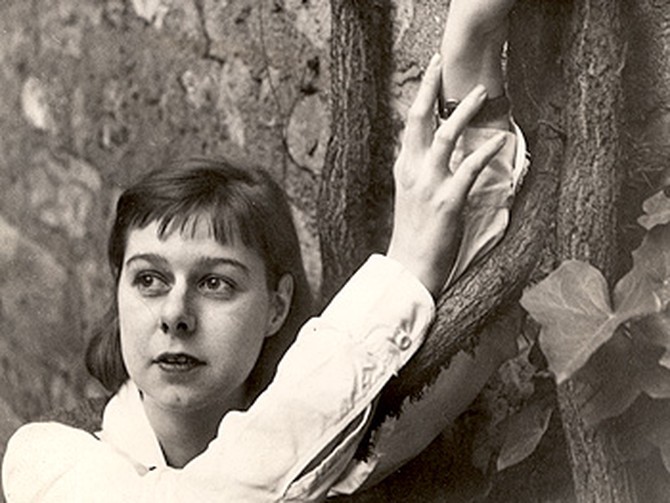

Carson's Literary Crowd

The February House

Located at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights, New York it was home to a charter membership of writers and artists that included Carson, Gypsy Rose Lee, W.H. Auden, Oliver Smith and George Davis. Writer Anais Nin gave the house its name when she discovered that Davis, Auden and McCullers had all been born under the sign of Pisces, and described it in her diary as "an amazing house, like some of the houses in Belgium, the north of France or Austria. It is like a museum of Americana which I had never seen anywhere before." Moving in October 1940 into two rooms on the second floor, McCullers says that she loved what she called "living in a real neighborhood."

Carson McCullers lived here on-and-off from 1940 to 1945, until the house was demolished by the city to make way for an expansion of the Brooklyn Bridge. While McCullers was in residence, the February House was home to a host of other notable artistic types, including writers Paul Bowles, Richard Wright and Christopher Isherwood and composers Leonard Bernstein, David Diamond, Peter Pears and Aaron Copeland.

Carson McCullers lived here on-and-off from 1940 to 1945, until the house was demolished by the city to make way for an expansion of the Brooklyn Bridge. While McCullers was in residence, the February House was home to a host of other notable artistic types, including writers Paul Bowles, Richard Wright and Christopher Isherwood and composers Leonard Bernstein, David Diamond, Peter Pears and Aaron Copeland.

George Davis, W.H. Auden and Gypsy Rose Lee

When novelist George Davis, member of the Algonquin Round Table and the young literary editor for Harper's Bazaar, found the sprawling three-story brownstone at 7 Middagh street, he invited two of his favorite people to move in with him—Carson McCullers and poet W.H. Auden. Frequently Gypsy Rose Lee, a statuesque striptease artist and burlesque entertainer who was also friends with George Davis, joined the other three for an evening meal or a jaunt to bars on nearby Sand Street.

McCullers was said to find Gypsy Rose Lee fascinating. She towered over the petite Carson and charmed her with her magnetic charisma—and both women came to hold their own with the gay repartee of W.H. Auden and George Davis. Auden was humorous and loved to play the clown; Davis was more genial and intellectual. The four of them, especially after Lee moved into the house in the fall of 1940, spent a great deal of time philosophizing, entertaining and cavorting. Over time, McCullers and Lee's friendship blossomed and they became close confidants during the year they lived together at February House. It is said to be on a walk with Lee when McCullers first imagined the "we of me" scene that later shaped her novella The Member of the Wedding.

McCullers was said to find Gypsy Rose Lee fascinating. She towered over the petite Carson and charmed her with her magnetic charisma—and both women came to hold their own with the gay repartee of W.H. Auden and George Davis. Auden was humorous and loved to play the clown; Davis was more genial and intellectual. The four of them, especially after Lee moved into the house in the fall of 1940, spent a great deal of time philosophizing, entertaining and cavorting. Over time, McCullers and Lee's friendship blossomed and they became close confidants during the year they lived together at February House. It is said to be on a walk with Lee when McCullers first imagined the "we of me" scene that later shaped her novella The Member of the Wedding.

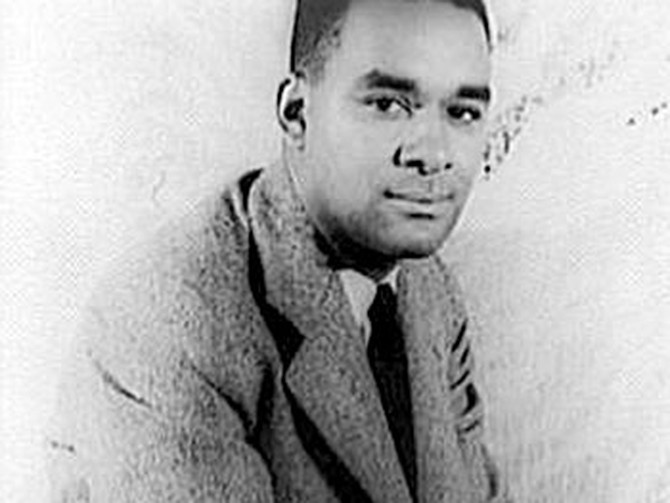

Richard Wright

Richard Wright had reviewed The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter in New Republic before he ever met Carson McCullers. In it he applauded her "astonishing humanity that enables a white writer, for the first time in Southern Fiction, to handle Negro characters with as much ease and justice as those of her own race."

Once he met her, it was not only her writing that attracted Wright to McCullers, but in his opinion also her "tortured soul, her zest for the ordinary moments of life." Frequently moody, Wright found his spirits lifted when McCullers greeted him. Wright felt a sense of brotherhood with the other writers in the February House while he lived there, and felt that McCullers was a positive force in the house during her first stay. The two reconnected in Paris in the fall of 1946 when they were both integral parts of the Paris and American literati, which at that time included Alice B. Toklas, James Baldwin, William Burroughs, Sherwood Anderson, Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean Cocteau and Samuel Beckett.

Once he met her, it was not only her writing that attracted Wright to McCullers, but in his opinion also her "tortured soul, her zest for the ordinary moments of life." Frequently moody, Wright found his spirits lifted when McCullers greeted him. Wright felt a sense of brotherhood with the other writers in the February House while he lived there, and felt that McCullers was a positive force in the house during her first stay. The two reconnected in Paris in the fall of 1946 when they were both integral parts of the Paris and American literati, which at that time included Alice B. Toklas, James Baldwin, William Burroughs, Sherwood Anderson, Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean Cocteau and Samuel Beckett.

Truman Capote

After the publication of McCullers's first two novels, she was known as a very influential Southern writer and someone other young (especially Southern) writers flocked to. Originally a friend of her sister Rita, McCullers met writer Truman Capote in 1946 at the Yaddo artists colony in Saratoga Springs, New York, where he was a humorous young newcomer working on his first book, Other Voices, Other Rooms. The Yaddo group at that time was very congenial, and McCullers and Capote became fast friends. Later that year when McCullers and husband Reeves were setting off for France, Capote appointed himself personal ambassador to help them off, and ended up staying at the McCullers's family home in Nyack, New York for several days attending to last minute details. McCullers, along with her sister Rita, was helpful in launching Truman's career, but in the end she felt ill-thanked for her help. After the publication of Capote's first two novels, McCullers became convinced that certain passages had been plagiarized from her own writings. Her retribution was swift—she broke ties with Capote and treated him standoffishly from then on.

Capote never lost his fondness for McCullers and her family, however, and is the only person to attend both Reeves funeral in Paris and McCullers's funeral in Nyack several years later.

Capote never lost his fondness for McCullers and her family, however, and is the only person to attend both Reeves funeral in Paris and McCullers's funeral in Nyack several years later.

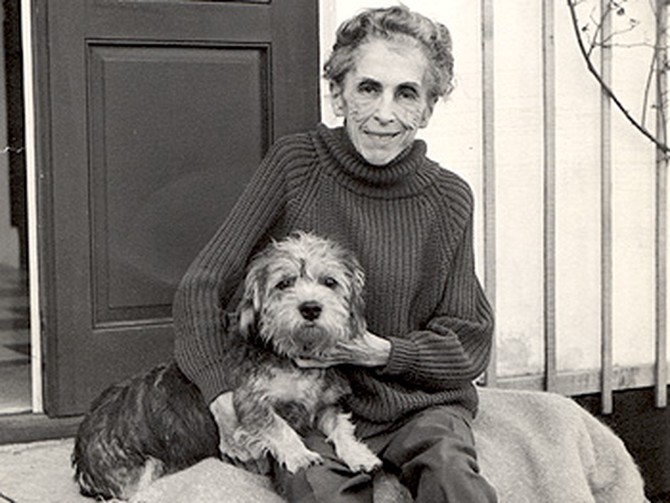

Isak Dinesen

In her early development as a writer, McCullers returned again and again to the writers she particularly admired, among them D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce, Katherine Mansfield, and Isak Dinesen, whose novel Out of Africa she discovered in 1937. She reread Dinesen's novels every year, and considered the Danish writer a creative idol. When Dinesen came to the United States in 1959 to address the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters, she said there were four Americans she'd like to meet: Carson McCullers, Marilyn Monroe, E. E. Cummings and Ernest Hemmingway. Dinesen and McCullers were seated next to each other at the dinner, and they were enthralled with one another. Of this dinner meeting, McCullers said: "When I met her, she was very, very frail and old but as she talked her face was lit like a candle in an old church."

After that, McCullers took it upon herself to host a luncheon where Dinesen could meet Marilyn Monroe. To McCullers, it was one of the best parties she had ever given—an infamous gathering between kindred souls. McCullers spoke of it with fondness for the rest of her life, and maintained a close friendship with Dinesen until Dinesen died in 1962.

After that, McCullers took it upon herself to host a luncheon where Dinesen could meet Marilyn Monroe. To McCullers, it was one of the best parties she had ever given—an infamous gathering between kindred souls. McCullers spoke of it with fondness for the rest of her life, and maintained a close friendship with Dinesen until Dinesen died in 1962.

Carson's European Compatriots

A social butterfly who operated according to her own ideas in social groups, Carson McCullers (along with husband Reeves until his death) was very popular with American ex-patriots in Europe, and also with European writers and artists that she met in Italy, France and England. Audacious in some ways, McCullers dropped in uninvited to writer Elizabeth Bowen and writer Dame Edith Sitwell's country estates during her travels abroad, and struck up an easy friendship with both.

Throughout the early 1950s, McCullers spent time with many of her oldest literary friends in Rome, including W.H. Auden, Truman Capote (who was much closer with Reeves by this time), Gore Vidal and Tennessee Williams. She maintained a great love of Western Europe even in her darkest hours, and made her last trip to Ireland shortly before her final stroke in 1967. Her travel was at the request of director John Huston, a close friend toward the end of her life, who was in the process of shooting the movie adaptation of Reflections in a Golden Eye.

Throughout the early 1950s, McCullers spent time with many of her oldest literary friends in Rome, including W.H. Auden, Truman Capote (who was much closer with Reeves by this time), Gore Vidal and Tennessee Williams. She maintained a great love of Western Europe even in her darkest hours, and made her last trip to Ireland shortly before her final stroke in 1967. Her travel was at the request of director John Huston, a close friend toward the end of her life, who was in the process of shooting the movie adaptation of Reflections in a Golden Eye.

Flannery O'Connor, Eudora Welty and Katherine Anne Porter

Of the Southern women writers who helped to pioneer the southern gothic literary tradition, the four majors were Carson McCullers, short-storytellers Flannery O'Connor and Katherine Anne Porter, and novelist Eudora Welty. Interestingly, they were all contemporaries, born around the same time and publishing major works in the 1940s and '50s. McCullers and O'Connor both died fairly young while Porter lived until 1980 and Welty to the ripe age of 90, dying in 2001.

Despite their closeness in age and some similarities in their themes and writing styles, the four were not close or particularly supportive of each other. McCullers met Porter on her first visit to Yaddo artist's colony, and they initially struck up a friendship that eroded when Porter and Welty became close in the mid-1940s. To some degree, all four writers were vying for a similar spot in literary infamy—a spot that at that time must have seemed rather limited: they were women from the seemingly unsophisticated South. Part of the intrigue of their legacy is that all of them did find success, and a lasting place in the annals of American literature and hearts of their readers.

Despite their closeness in age and some similarities in their themes and writing styles, the four were not close or particularly supportive of each other. McCullers met Porter on her first visit to Yaddo artist's colony, and they initially struck up a friendship that eroded when Porter and Welty became close in the mid-1940s. To some degree, all four writers were vying for a similar spot in literary infamy—a spot that at that time must have seemed rather limited: they were women from the seemingly unsophisticated South. Part of the intrigue of their legacy is that all of them did find success, and a lasting place in the annals of American literature and hearts of their readers.

Tennessee Williams

Of all Carson McCullers's literary friendships, her close relationship with playwright Tennessee Williams was the most significant and lasting. There are several pieces of correspondence between the two that survive, and paint a portrait of very tender and devoted friends. Not only were they confidants, they also enjoyed a bond of mutual respect for one another's writing and writing process. It was this bond that spurred each of them, at times, to new heights in their own literary output.

In the summer and fall of 1948, at Williams' suggestion while they were vacationing together in Nantucket, McCullers revised her novella The Member of the Wedding into a play that later earned her fame on the Broadway stage. In the end, Williams was a lifelong supporter of Carson and her work. He called her second novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye a pure and powerful work "conceived in that Sense of the Awful that is the desperate black root of nearly all significant modern art." In a touching introduction to Virginia Spencer Carr's biography The Lonely Hunter: A Biography of Carson McCullers Williams said this of his dear friend, "Carson's heart was often lonely and it was a tireless hunter for those to whom she could offer it, but it was a heart that was graced with light that eclipsed the shadows."

In the summer and fall of 1948, at Williams' suggestion while they were vacationing together in Nantucket, McCullers revised her novella The Member of the Wedding into a play that later earned her fame on the Broadway stage. In the end, Williams was a lifelong supporter of Carson and her work. He called her second novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye a pure and powerful work "conceived in that Sense of the Awful that is the desperate black root of nearly all significant modern art." In a touching introduction to Virginia Spencer Carr's biography The Lonely Hunter: A Biography of Carson McCullers Williams said this of his dear friend, "Carson's heart was often lonely and it was a tireless hunter for those to whom she could offer it, but it was a heart that was graced with light that eclipsed the shadows."

Published 01/01/2006