The Day a Stranger Taught Gloria Steinem a Lesson She Never Forgot

The woman synonymous with American feminism has learned her most important lessons in the company of strangers.

Photo: Gloria Steinem Papers, Sophia Smith Collection

Gloria Steinem is often asked why she still has hope and energy after more than 50 years as an activist. Her answer: "Because I travel." My Life on the Road (Random House) chronicles her itinerant adventures and the connections she's made all over the world as a result. The memoir, like Steinem herself, is thoughtful and astonishingly humble. It is also filled with a sense of the momentous while offering deeply personal insights into what shaped her, among them this simple coda: "We have to behave as if everything we do matters," she writes. "Because it might." In this excerpt, she recalls one of the days that mattered the most.

In 1963, I was making a living as a freelance journalist, writing style pieces and profiles of celebrities—not the kind of writing I had imagined when I came home from India after two years of traveling and studying there in the late 1950s. One day I read that Martin Luther King Jr. was leading a March on Washington—a massive campaign for jobs, justice, new legislation, and federal protection for civil rights marchers who were being beaten, jailed, and sometimes murdered in the South, all with police collusion. However, I couldn't get an assignment to write about it.

Steinem with new friends in Calcutta, circa 1957.

For all those reasons, I decided not to go to the march—right up until I found myself on my way.

All I can say years later is: If you find yourself drawn to something against all logic, go for it. The universe is telling you something.

On that hot August day, I was just one person being carried slowly along in a sea of humanity. I washed up next to "Mrs. Greene with an e," an older, plump woman wearing a straw hat who was marching with her grown-up, elegant daughter. As Mrs. Greene explained, she had worked in Washington during the Truman administration, in the same big room as white clerks, yet she had been segregated behind a screen. She hadn't been able to protest then, so she was protesting now.

As we neared the Lincoln Memorial, Mrs. Greene pointed out that the only woman seated on the speakers' platform was Dorothy Height, head of the National Council of Negro Women, an organization that had been doing the work of racial justice since the 1930s, and even she hadn't been asked to speak. Mrs. Greene wanted to know: Where is Ella Baker? She trained all those SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] young people. What about Fannie Lou Hamer? She got beaten up in jail and sterilized in a Mississippi hospital when she went in for something else entirely. That's what happens—we're supposed to give birth to field hands when they need them, and not when they don't. My grandmother was dirt poor and got paid seventy-five dollars for every live birth. The difference between her and Fannie Lou? Farm equipment. They didn't need so many field hands anymore. This is black women's story, from rape to sterilization. Who will speak about that?

I had not even noticed the absence of women speakers. And I'd never thought about the racial reasons for controlling women's bodies. I felt a gear click into place in my mind. It was like India, where high-caste women were restricted and women at the bottom were exploited. Living in India had made me aware of how segregated my own country was. But Mrs. Greene made me understand the parallels between race and caste—and between women forced to give birth as society dictated. Different prisons. Same key.

Mrs. Greene's daughter rolled her eyes as her mother told me about complaining to their state delegation leader. He had countered that Mahalia Jackson and Marian Anderson were singing. Singing isn't speaking, she told him in no uncertain terms.

I was impressed. Not only had I never made any such complaints, but at political meetings I had given my suggestions to whatever man was sitting next to me, knowing that if a man offered them, they would be taken more seriously. You white women, Mrs. Greene said kindly, as if reading my mind, if you don't stand up for yourselves, how can you stand up for anybody else?

As streams of people surged toward the Lincoln Memorial and the speakers' platform, the three of us were separated. I used my press credentials to climb the steps, hoping to see Mrs. Greene and her daughter. But when I turned around, what I saw instead was a vista I will never forget. Stretching over the expanse of green, past the reflecting pool, past the Washington Monument, all the way to the Capitol, were a quarter of a million people. They looked calm, peaceful, not even pressing to come closer to the speakers, as if each individual felt responsible for proving that the fears of violence were wrong. We were like a nation within a nation. I thought: I wouldn't be anywhere else on this earth.

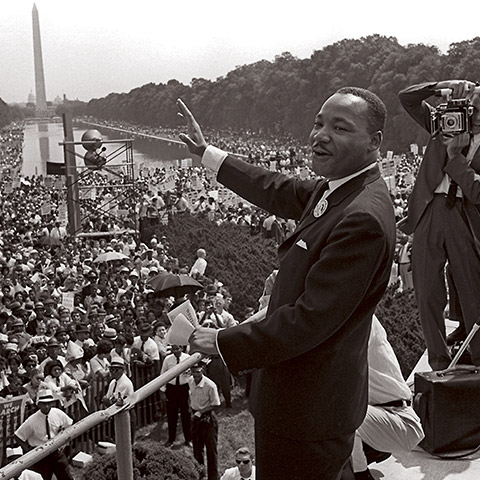

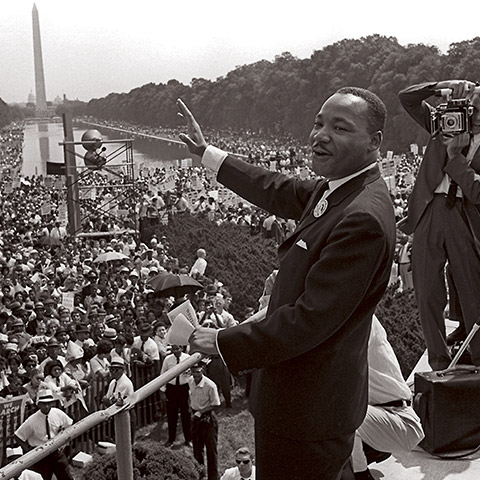

Martin Luther King Jr. waving to supporters during the March on Washington, 1963.

As King ended his speech, I heard Mahalia Jackson call out, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!" And he began the "I have a dream" litany from memory, with the crowd calling out to him after each image—Tell it! What would be most remembered had been least planned.

I hoped Mrs. Greene heard a woman speak—and make all the difference.

Steinem in 1965.

In 1963, I was making a living as a freelance journalist, writing style pieces and profiles of celebrities—not the kind of writing I had imagined when I came home from India after two years of traveling and studying there in the late 1950s. One day I read that Martin Luther King Jr. was leading a March on Washington—a massive campaign for jobs, justice, new legislation, and federal protection for civil rights marchers who were being beaten, jailed, and sometimes murdered in the South, all with police collusion. However, I couldn't get an assignment to write about it.

Steinem with new friends in Calcutta, circa 1957.

Ivan Massar/Take Stock/The Image Works

True, I did have a long-sought assignment to write a profile of James Baldwin—who was expected to speak at the march—but the prospect of following him around amid multitudes seemed impossible, intrusive, or both. Plus I'd be able to see and hear his speech better on television. Also, the press was full of dire warnings about too few people and a failed event, or too many people and violence. The march was being called too dangerous (by a White House worried that it could turn off moderates in Congress who were needed to pass the Civil Rights Act), and too tame (by Malcolm X, who said that asking for help from Washington was needy, not self-sufficient, and unlikely to succeed).

For all those reasons, I decided not to go to the march—right up until I found myself on my way.

All I can say years later is: If you find yourself drawn to something against all logic, go for it. The universe is telling you something.

On that hot August day, I was just one person being carried slowly along in a sea of humanity. I washed up next to "Mrs. Greene with an e," an older, plump woman wearing a straw hat who was marching with her grown-up, elegant daughter. As Mrs. Greene explained, she had worked in Washington during the Truman administration, in the same big room as white clerks, yet she had been segregated behind a screen. She hadn't been able to protest then, so she was protesting now.

As we neared the Lincoln Memorial, Mrs. Greene pointed out that the only woman seated on the speakers' platform was Dorothy Height, head of the National Council of Negro Women, an organization that had been doing the work of racial justice since the 1930s, and even she hadn't been asked to speak. Mrs. Greene wanted to know: Where is Ella Baker? She trained all those SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] young people. What about Fannie Lou Hamer? She got beaten up in jail and sterilized in a Mississippi hospital when she went in for something else entirely. That's what happens—we're supposed to give birth to field hands when they need them, and not when they don't. My grandmother was dirt poor and got paid seventy-five dollars for every live birth. The difference between her and Fannie Lou? Farm equipment. They didn't need so many field hands anymore. This is black women's story, from rape to sterilization. Who will speak about that?

I had not even noticed the absence of women speakers. And I'd never thought about the racial reasons for controlling women's bodies. I felt a gear click into place in my mind. It was like India, where high-caste women were restricted and women at the bottom were exploited. Living in India had made me aware of how segregated my own country was. But Mrs. Greene made me understand the parallels between race and caste—and between women forced to give birth as society dictated. Different prisons. Same key.

Mrs. Greene's daughter rolled her eyes as her mother told me about complaining to their state delegation leader. He had countered that Mahalia Jackson and Marian Anderson were singing. Singing isn't speaking, she told him in no uncertain terms.

I was impressed. Not only had I never made any such complaints, but at political meetings I had given my suggestions to whatever man was sitting next to me, knowing that if a man offered them, they would be taken more seriously. You white women, Mrs. Greene said kindly, as if reading my mind, if you don't stand up for yourselves, how can you stand up for anybody else?

As streams of people surged toward the Lincoln Memorial and the speakers' platform, the three of us were separated. I used my press credentials to climb the steps, hoping to see Mrs. Greene and her daughter. But when I turned around, what I saw instead was a vista I will never forget. Stretching over the expanse of green, past the reflecting pool, past the Washington Monument, all the way to the Capitol, were a quarter of a million people. They looked calm, peaceful, not even pressing to come closer to the speakers, as if each individual felt responsible for proving that the fears of violence were wrong. We were like a nation within a nation. I thought: I wouldn't be anywhere else on this earth.

Martin Luther King Jr. waving to supporters during the March on Washington, 1963.

Photo: AFP/Getty Images

Martin Luther King Jr. read his much-anticipated speech in a deep and familiar voice. I'd always imagined that if I were present at an historic moment, I would know it only long afterward, but I recognized this was history in the moment.

As King ended his speech, I heard Mahalia Jackson call out, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!" And he began the "I have a dream" litany from memory, with the crowd calling out to him after each image—Tell it! What would be most remembered had been least planned.

I hoped Mrs. Greene heard a woman speak—and make all the difference.

Steinem in 1965.

Photo: Yale Joel/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images