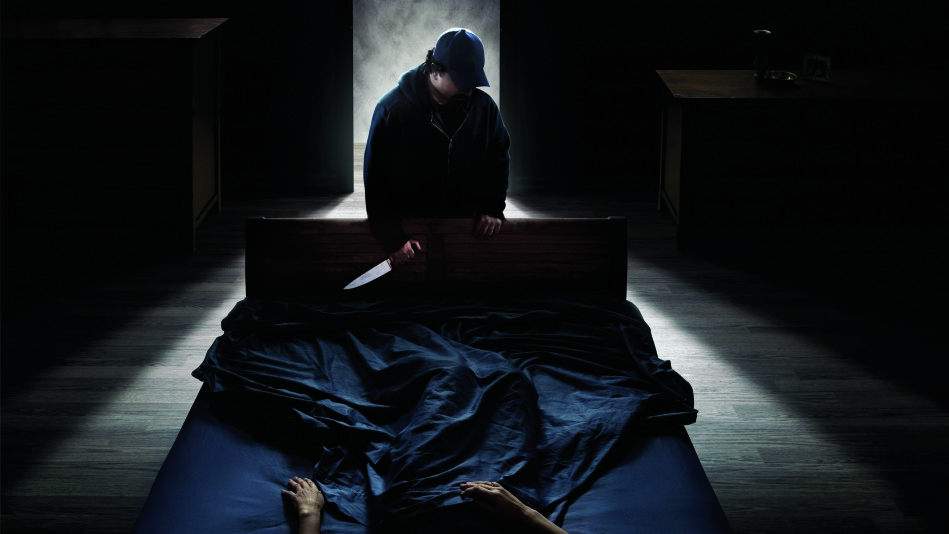

Photo Illustration: Jonathan Barkat

I was raped one night last summer in Miguel de Allende, Mexico, where I live. A friend and his sister had come over for dinner, and soon after they left, at 10:30, a neighbor came knocking. Water was gushing into her house from a construction site next door. I knew the builder, and the neighbor asked if I would call to tell him. I went upstairs, called the builder, then forgot to go back down and double lock the door. I was on the Internet, absorbed in looking up Benedictine monasteries, a recent preoccupation. I was investigating becoming a contemplative nun, trying to find a community that seemed right for me. At 12:10, shocked to be up so late, I put aside my laptop and promptly went to sleep.

At approximately 1 A.M., I was awakened by a rapist in my bed, his head inches from my own, a knife in his hand. I could make out the dark silhouette of a roundish man in a baseball cap, propped on his elbow beside me. I knew immediately who he was—the serial rapist who'd terrorized my town for the past eight months.

"Shhh, don't scream," he said in accented English. "I have a knife."

I recognized it immediately as the knife I'd cut limes with earlier and left on the counter. "Don't do this," I heard myself say. "This is not right. It's sick."

He told me I talked too much. He waved the knife closer to my face.

"Now I will be raped," I thought.

And a worse thought: "I could lose my faith in God. After all my devotion, God has permitted this."

I began to tremble.

"I'm going to be sick," I said. He knocked the heel of his hand on my shoulder. "Calm down," he said. "Look," and he placed the knife on the little altar beside the bed. "It's all right."

I will not write the details of the rape itself. Suffice it to say that I kept my arms crossed against my chest and my head turned away. The sexual ordeal lasted three minutes, the violating member was one inch long, the rapist never touched any other place on my body. Afterward he wanted to talk. "Are you Ingleterra?" he asked. "What's your name? Is your name Penelope? I see you on the street. You look good. Are you married? Where are you from?"

> I am blessed to live in a community of strong women, four of whom had been raped by this man. They had not hidden away in shame but let the details of their rapes be known. And so I was aware that the first two women had fought him and been badly beaten. The next two women had not resisted and escaped physically unharmed except for the horrific sexual violation. I knew, too, that the rapist stayed for four or five hours, repeating his sexual assaults, that he liked to talk, to confess that he is a sick man who can't help himself, a confession that would arouse him again. So I decided not to answer one question, not to engage him in any conversation. I would pray in order to freak him out.

I said the first Hail Mary in English, then realized I should be using the language of this man's childhood: "Dios te salve Maria..."

> "Stop it," he said. I said, "I'm praying for you"—which had not been true, but as soon as I said the words I understood that praying for him would be a very good thing to do, that I should be praying for him. So now, saying the next Hail Mary, I asked God, Jesus, the Virgin, the Holy Spirit, all the angels and saints and any other mystical agent of good to make this man see the harm he was doing. He kept talking as I prayed, patted my shoulder, told me everything would be okay, asked if I wanted wine or beer.

At approximately 1 A.M., I was awakened by a rapist in my bed, his head inches from my own, a knife in his hand. I could make out the dark silhouette of a roundish man in a baseball cap, propped on his elbow beside me. I knew immediately who he was—the serial rapist who'd terrorized my town for the past eight months.

"Shhh, don't scream," he said in accented English. "I have a knife."

I recognized it immediately as the knife I'd cut limes with earlier and left on the counter. "Don't do this," I heard myself say. "This is not right. It's sick."

He told me I talked too much. He waved the knife closer to my face.

"Now I will be raped," I thought.

And a worse thought: "I could lose my faith in God. After all my devotion, God has permitted this."

I began to tremble.

"I'm going to be sick," I said. He knocked the heel of his hand on my shoulder. "Calm down," he said. "Look," and he placed the knife on the little altar beside the bed. "It's all right."

I will not write the details of the rape itself. Suffice it to say that I kept my arms crossed against my chest and my head turned away. The sexual ordeal lasted three minutes, the violating member was one inch long, the rapist never touched any other place on my body. Afterward he wanted to talk. "Are you Ingleterra?" he asked. "What's your name? Is your name Penelope? I see you on the street. You look good. Are you married? Where are you from?"

> I am blessed to live in a community of strong women, four of whom had been raped by this man. They had not hidden away in shame but let the details of their rapes be known. And so I was aware that the first two women had fought him and been badly beaten. The next two women had not resisted and escaped physically unharmed except for the horrific sexual violation. I knew, too, that the rapist stayed for four or five hours, repeating his sexual assaults, that he liked to talk, to confess that he is a sick man who can't help himself, a confession that would arouse him again. So I decided not to answer one question, not to engage him in any conversation. I would pray in order to freak him out.

I said the first Hail Mary in English, then realized I should be using the language of this man's childhood: "Dios te salve Maria..."

> "Stop it," he said. I said, "I'm praying for you"—which had not been true, but as soon as I said the words I understood that praying for him would be a very good thing to do, that I should be praying for him. So now, saying the next Hail Mary, I asked God, Jesus, the Virgin, the Holy Spirit, all the angels and saints and any other mystical agent of good to make this man see the harm he was doing. He kept talking as I prayed, patted my shoulder, told me everything would be okay, asked if I wanted wine or beer.

I switched to a Padre Nuestro, a loud one to let him know I was not listening to him. And I was struck by a new thought: I pray to the Virgin Mary for help every day, why wasn't I praying to her for help for myself right now? I began another Salve Maria, this time imploring the Virgin to get this man out of my bed and out of my house. Amazingly, seconds later, the rapist said, "Okay, I'm going," kissed me on the cheek, and backed out of the bed. I continued to pray as he said, "Goodbye, you'll be okay. Don't call the police."

As soon as I heard the door slam shut, I ran down the steps and locked the front door. As I walked back up the stairs, a dribble of sperm leaked onto my inner thigh and I considered the night ahead. The interrogation, the medical exam, the humiliating details confessed to strangers could feel like as much of a violation as the rape. It was possible, I realized, not even to call the police. Did I really want the whole town to know? Did I want to cause my son pain? Did I want to go through the rest of my life being known as a woman who had been raped? A victim? How I've always hated that word.

But before two minutes had passed, I understood I had no choice. People needed to know that the rapist had struck again, that he had not left town. It was my duty to report the crime.

I called my friends a block away, Caren and David Cross. Caren reached the police, and an army of them—on horseback, motorcycles, piled into trucks—arrived at my house even before Caren and David did. They were courteous and concerned. I was taken to the Ministerio Público, where, flanked by David and Caren, I told a competent and compassionate woman, a lawyer, the whole story.

Outside the office, a plainclothes detective pulled up a chair and told me to tell him every detail of what had happened. I began; moments later, feeling intensely irritated at having to relive it all, especially because this man was leaning in entirely too closely, I said, "I'm not telling you. I'm not repeating the story again."

I began in that instant to take back my power.

At dawn, after the report had been typed and the medical examiner had taken digital photos of my vagina along with a DNA sample, Caren and I drove back to my house, where 20 men combed through the rooms and the grounds, collecting evidence. A rope ladder still hung from my balcony rail.

Two state detectives arrived. It was very important, they said, that I tell them everything I could remember. "Read the report!" I said, then explained more calmly that I'd been traumatized enough for one night.

As soon as I heard the door slam shut, I ran down the steps and locked the front door. As I walked back up the stairs, a dribble of sperm leaked onto my inner thigh and I considered the night ahead. The interrogation, the medical exam, the humiliating details confessed to strangers could feel like as much of a violation as the rape. It was possible, I realized, not even to call the police. Did I really want the whole town to know? Did I want to cause my son pain? Did I want to go through the rest of my life being known as a woman who had been raped? A victim? How I've always hated that word.

But before two minutes had passed, I understood I had no choice. People needed to know that the rapist had struck again, that he had not left town. It was my duty to report the crime.

I called my friends a block away, Caren and David Cross. Caren reached the police, and an army of them—on horseback, motorcycles, piled into trucks—arrived at my house even before Caren and David did. They were courteous and concerned. I was taken to the Ministerio Público, where, flanked by David and Caren, I told a competent and compassionate woman, a lawyer, the whole story.

Outside the office, a plainclothes detective pulled up a chair and told me to tell him every detail of what had happened. I began; moments later, feeling intensely irritated at having to relive it all, especially because this man was leaning in entirely too closely, I said, "I'm not telling you. I'm not repeating the story again."

I began in that instant to take back my power.

At dawn, after the report had been typed and the medical examiner had taken digital photos of my vagina along with a DNA sample, Caren and I drove back to my house, where 20 men combed through the rooms and the grounds, collecting evidence. A rope ladder still hung from my balcony rail.

Two state detectives arrived. It was very important, they said, that I tell them everything I could remember. "Read the report!" I said, then explained more calmly that I'd been traumatized enough for one night.

By the time everyone left, it was 10 in the morning. I had not slept and did not feel tired. In fact I felt rather energetic—and on a mission. The rapist had begun his attacks eight months earlier, scaling walls, lassoing balcony rails, removing skylights, cutting through glass. Women had installed alarm systems and put bars on their windows. They bought Mace and adopted dogs. One friend bolted herself into her bedroom every night and peed in a potty. Everywhere we walked, we were aware he might be observing us. It was a reign of terror. But the rapist hadn't struck for four months and we had begun to feel safe, even complacent. I had to let the town know what had happened. Women needed to become vigilant again. I had been lax. I hadn't locked my upstairs patio door or double locked my front door. If I had, the rape might never have happened.

I asked Caren to post a notice on the town's website. And as weeping friends flooded into my house, I began to believe that if anyone had to be raped, it was good that it was me. The rape was just one more knock in a life of hard knocks. I could handle it. Plus I was a writer. I could write about it; I could be the messenger.

Virtually nothing had been publicized about the crimes in the local English-language paper. So I did an article sharing everything I'd learned from the other victims and the police. "The rapist has a pattern," I wrote. "He rapes women between 50 and 60 who live alone. He stalks them and attacks in their homes between 1 and 2 in the morning. The rapist needs to dominate, to feel powerful. If you fight you enrage him because you have ruined his fantasy, and if you act terrified you titillate him." At the end of the article, I wrote: "The outpouring of love and concern from both foreign and Mexican communities has been heartening and healing. I have always heard that we are all one. I never quite understood it the way I do now. Each time I'd heard how a woman among us had been raped, I felt sick and outraged. Now I am the one who was raped, and am the instrument of suffering. One person is hurt and everyone hurts. This is easy to see because we are a community. But it applies to the whole world. In our community, there is a sick member. That is all that he is."

The article was published exactly one week after the rape. Accompanying the article was the Hail Mary in Spanish. In shops notices appeared in Spanish and English saying that "a courageous sister" was raped and that by praying the Hail Mary she found strength. All over town English-speaking women kept the Hail Mary in Spanish by their beds, they carried it in their bags when they left home, they memorized it, and they prayed it.

People in town were saying that the energy felt different, lighter. People began to believe this man would be caught.

Meanwhile the police informed me that I was at high risk for a return attack. I stayed every night at Caren and Dave's. But during the day, even though it was scary imagining the rapist watching from the field beyond my courtyard walls, I lived in my house. I'd be damned if I'd let him keep me from my home.

Rapists are notoriously hard to catch. But five days after my article appeared, five days after everyone began praying, at 11 in the evening on the corner of my street, carrying a rope with a hook fastened to the end, he was caught.

I didn't have to be strong anymore, and I collapsed. I had no defenses. I cried because I'd been raped. And I cried at the drop of a hat. Strangely, while the rapist was still at large, it had not for one moment occurred to me to leave town. A friend had invited me to her cottage on Lake Huron, which I'd refused. Now I accepted. Walking all over the island, kayaking, skinny-dipping, canoeing, playing Scrabble with her other guests, I began to heal. One evening I wept to my friend. I needed to talk about what had happened, I said, but I felt that no one wanted to hear. She told me to talk as much as I wanted.

And so I did. As I write this article, it has been six months since the attack. It seems much longer. It was disturbing to be a celebrity because I'd been raped. But that has been more than made up for by the people thanking me for writing about it. Or the people who've approached me simply to say, "I'm sorry about what happened to you."

But most important, what happened has strengthened my faith in God and in prayer. When the rapist came into bed, I felt that God had betrayed me. But once I'd remembered to ask for help, I'd received it. Praying had turned despair into faith. And then the whole town prayed with me, and the rapist was caught. I am unutterably grateful that the rapist is behind bars.

I still talk about what happened to me once in a while, the way I might talk about having been caught in a tsunami. Rape has been a plague through all of history. It happens to women everywhere. It happens all the time. So why not admit that it happened to me?

Please, if you are ever raped, think of it as a physical attack that has absolutely nothing to do with sex as a tender act. Shout out loudly and open yourself to the respect due a survivor. You have done nothing to be ashamed of. The rapist has.

Beverly Donofrio is the author of Mary and the Mouse, the Mouse and Mary, a children's book from Random House

I asked Caren to post a notice on the town's website. And as weeping friends flooded into my house, I began to believe that if anyone had to be raped, it was good that it was me. The rape was just one more knock in a life of hard knocks. I could handle it. Plus I was a writer. I could write about it; I could be the messenger.

Virtually nothing had been publicized about the crimes in the local English-language paper. So I did an article sharing everything I'd learned from the other victims and the police. "The rapist has a pattern," I wrote. "He rapes women between 50 and 60 who live alone. He stalks them and attacks in their homes between 1 and 2 in the morning. The rapist needs to dominate, to feel powerful. If you fight you enrage him because you have ruined his fantasy, and if you act terrified you titillate him." At the end of the article, I wrote: "The outpouring of love and concern from both foreign and Mexican communities has been heartening and healing. I have always heard that we are all one. I never quite understood it the way I do now. Each time I'd heard how a woman among us had been raped, I felt sick and outraged. Now I am the one who was raped, and am the instrument of suffering. One person is hurt and everyone hurts. This is easy to see because we are a community. But it applies to the whole world. In our community, there is a sick member. That is all that he is."

The article was published exactly one week after the rape. Accompanying the article was the Hail Mary in Spanish. In shops notices appeared in Spanish and English saying that "a courageous sister" was raped and that by praying the Hail Mary she found strength. All over town English-speaking women kept the Hail Mary in Spanish by their beds, they carried it in their bags when they left home, they memorized it, and they prayed it.

People in town were saying that the energy felt different, lighter. People began to believe this man would be caught.

Meanwhile the police informed me that I was at high risk for a return attack. I stayed every night at Caren and Dave's. But during the day, even though it was scary imagining the rapist watching from the field beyond my courtyard walls, I lived in my house. I'd be damned if I'd let him keep me from my home.

Rapists are notoriously hard to catch. But five days after my article appeared, five days after everyone began praying, at 11 in the evening on the corner of my street, carrying a rope with a hook fastened to the end, he was caught.

I didn't have to be strong anymore, and I collapsed. I had no defenses. I cried because I'd been raped. And I cried at the drop of a hat. Strangely, while the rapist was still at large, it had not for one moment occurred to me to leave town. A friend had invited me to her cottage on Lake Huron, which I'd refused. Now I accepted. Walking all over the island, kayaking, skinny-dipping, canoeing, playing Scrabble with her other guests, I began to heal. One evening I wept to my friend. I needed to talk about what had happened, I said, but I felt that no one wanted to hear. She told me to talk as much as I wanted.

And so I did. As I write this article, it has been six months since the attack. It seems much longer. It was disturbing to be a celebrity because I'd been raped. But that has been more than made up for by the people thanking me for writing about it. Or the people who've approached me simply to say, "I'm sorry about what happened to you."

But most important, what happened has strengthened my faith in God and in prayer. When the rapist came into bed, I felt that God had betrayed me. But once I'd remembered to ask for help, I'd received it. Praying had turned despair into faith. And then the whole town prayed with me, and the rapist was caught. I am unutterably grateful that the rapist is behind bars.

I still talk about what happened to me once in a while, the way I might talk about having been caught in a tsunami. Rape has been a plague through all of history. It happens to women everywhere. It happens all the time. So why not admit that it happened to me?

Please, if you are ever raped, think of it as a physical attack that has absolutely nothing to do with sex as a tender act. Shout out loudly and open yourself to the respect due a survivor. You have done nothing to be ashamed of. The rapist has.

Beverly Donofrio is the author of Mary and the Mouse, the Mouse and Mary, a children's book from Random House