How the 'School of Life' Can Help You Find Big Answers to Big Questions

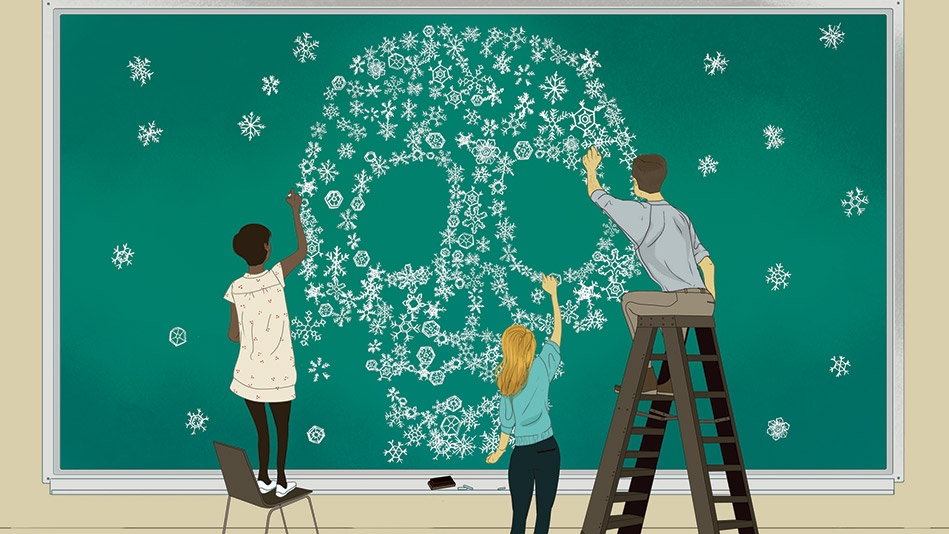

Illustration: Marcos Chin

PAGE 2

I've always been privately appalled by group therapy. All those judgmental strangers in chairs circled like one of the descending rings of hell. However, at the School of Life I found my fellow students funny and charming, prone to saying things like "People with a high degree of self-mastery and self-knowledge—I envy those bastards." In How to Stay Calm, everyone shared the triggers of their anxiety and rage, like transatlantic flights or the ex-husband who's "an absolute knob." None of it applied to me, and I wrote smugly in my notes, "No big revelations here." Then a 50-something man with the tiniest hole in his wool sweater said with urgency, "What if your anxiety is more low-level but...chronic? Since I turned 40, I've been walking around with it all the time." I sat up straighter then. I knew this song by heart.

The anxiety of aging doesn't make my palms clammy. I'll just be looking into a mirror with my head tilted a tiny bit and I'll see it—the skin that pulls at the hollow of my neck, so thin and delicate that I might as well be made of linen. Then the fear slips up from behind and puts me in a choke hold. But when I look around at the bright world with its crisp edges, everyone is joking about wrinkles, each passing birthday that, hardy har, "beats the alternative!" It was a balm to see another human being carrying the same burden I did, this middle manager type who could be standing behind me in a sandwich line. I fought the urge to turn to him and shout, "Me too!" I didn't think I'd ever fully felt the power of those two words.

When I caught up with him at the break, he said, "What did you do for your 40th? I just went into a cave." I brightened: "Oh, a cave! Where?" He said, "Er, not an actual cave. I just stayed in my apartment." I asked, "It gets better, though, right?" He looked at me kindly and answered, "Somewhat."

All these insights about reflection and connection smelled suspiciously like epiphanies. Suspicious is how I felt about epiphanies, because my own never lasted: I'd open my heart to humanity, and then some nimrod would block the napkin dispenser at Starbucks and I'd have to close it again. What good is a redemption story if you can't stay redeemed? I put this question to Roman Krznaric, one of the school's founding faculty members. (I highly recommend his latest book, Empathy: Why It Matters, and How to Get It—light on the exercises.)

"We do a course in mindfulness or we take a dance class, and we feel full of inspiration—but the feeling fades," he said. "The reality is that we don't 'find' meaning or direction but grow them, through the rough-and-tumble of life. There's a lovely Leonardo da Vinci line—he declared that experience was his mistress. That's how we learn, through experiment and change."

Experiment and change could take a long time, and writing a check takes a second—which may be why I once paid several hundred dollars for a class on how to breathe. When it was over, I stopped breathing in any kind of organized way, and I felt betrayed. I had shown up, and paid. Wasn't that enough? This is what happens in a free-market economy where we have little time and less patience, Krznaric told me: Once we've thrown money at a problem, we want an on-the-spot solution, preferably with a warranty. He said lightly, "You wanted to buy your happiness."

I thought about experiments—a cornerstone of the scientific method, as I learned in high school when we shattered our cryogenically frozen banana. No one performs an experiment once and considers her work done. She repeats it with different variables, correcting what she thought she knew, incorporating what she's learned. Without tests, we'd never get to the facts. Why should it be so different with the truth?

The classes on creativity and ambition were packed, but there were only about 15 students in How to Face Death. (They'd told me at the front desk that this one can be a hard sell.) One woman had come because her 98-year-old mother was dying of cancer and refused to acknowledge it. A slightly graying man nodded to the woman beside him and said, "It's our anniversary, and my wife thought this would be a nice way to end the week."

My own crisis of mortality had unspooled when my cat died, the year I turned 40. After the vet gave her that last shot, it was over so fast: She was there, and then she wasn't, and I was left holding her blankets. She'd been with me 18 years. Living suddenly seemed more conditional than it had before. I couldn't stand to put my ear to my husband's chest because his heart might stop beating while I lay there listening.

In class we learned that the American education activist Parker J. Palmer once compared death to winter, which "clears the landscape." Newcomers to the upper Midwest, he wrote, are often advised: "The winters will drive you crazy until you learn to get out into them." Walk straight ahead into winter—literal or metaphorical—or the dread of it will rule your life.

Our exercise, adapted from poet Stephen Levine's A Year to Live, was our walk into winter: We'd imagine that we were going to die in 365 days and plan the time we had left, month by month: conversations we'd like to have, things we'd longed to do.

I'd always assumed I'd...travel. I'd travel to...where? I wrote "Asia" because that covered a lot of ground. I wrote "India," and then put a question mark because it's so hot. I looked at the blank spots on the page. Filling them would have to be my homework. When I got around to it.

I'd forgotten the greatest thing about school—the feeling of possibility, that I was about to be launched into a wide world of imagination and ingenuity and beauty. Being a student again had reminded me of that expansiveness, as I made notes, asked questions, let experience—that saucy minx—be my mistress. I'd discovered that the wide world had been there all along, right where I had left it. And I considered that lesson enough.

The anxiety of aging doesn't make my palms clammy. I'll just be looking into a mirror with my head tilted a tiny bit and I'll see it—the skin that pulls at the hollow of my neck, so thin and delicate that I might as well be made of linen. Then the fear slips up from behind and puts me in a choke hold. But when I look around at the bright world with its crisp edges, everyone is joking about wrinkles, each passing birthday that, hardy har, "beats the alternative!" It was a balm to see another human being carrying the same burden I did, this middle manager type who could be standing behind me in a sandwich line. I fought the urge to turn to him and shout, "Me too!" I didn't think I'd ever fully felt the power of those two words.

When I caught up with him at the break, he said, "What did you do for your 40th? I just went into a cave." I brightened: "Oh, a cave! Where?" He said, "Er, not an actual cave. I just stayed in my apartment." I asked, "It gets better, though, right?" He looked at me kindly and answered, "Somewhat."

All these insights about reflection and connection smelled suspiciously like epiphanies. Suspicious is how I felt about epiphanies, because my own never lasted: I'd open my heart to humanity, and then some nimrod would block the napkin dispenser at Starbucks and I'd have to close it again. What good is a redemption story if you can't stay redeemed? I put this question to Roman Krznaric, one of the school's founding faculty members. (I highly recommend his latest book, Empathy: Why It Matters, and How to Get It—light on the exercises.)

"We do a course in mindfulness or we take a dance class, and we feel full of inspiration—but the feeling fades," he said. "The reality is that we don't 'find' meaning or direction but grow them, through the rough-and-tumble of life. There's a lovely Leonardo da Vinci line—he declared that experience was his mistress. That's how we learn, through experiment and change."

Experiment and change could take a long time, and writing a check takes a second—which may be why I once paid several hundred dollars for a class on how to breathe. When it was over, I stopped breathing in any kind of organized way, and I felt betrayed. I had shown up, and paid. Wasn't that enough? This is what happens in a free-market economy where we have little time and less patience, Krznaric told me: Once we've thrown money at a problem, we want an on-the-spot solution, preferably with a warranty. He said lightly, "You wanted to buy your happiness."

I thought about experiments—a cornerstone of the scientific method, as I learned in high school when we shattered our cryogenically frozen banana. No one performs an experiment once and considers her work done. She repeats it with different variables, correcting what she thought she knew, incorporating what she's learned. Without tests, we'd never get to the facts. Why should it be so different with the truth?

The classes on creativity and ambition were packed, but there were only about 15 students in How to Face Death. (They'd told me at the front desk that this one can be a hard sell.) One woman had come because her 98-year-old mother was dying of cancer and refused to acknowledge it. A slightly graying man nodded to the woman beside him and said, "It's our anniversary, and my wife thought this would be a nice way to end the week."

My own crisis of mortality had unspooled when my cat died, the year I turned 40. After the vet gave her that last shot, it was over so fast: She was there, and then she wasn't, and I was left holding her blankets. She'd been with me 18 years. Living suddenly seemed more conditional than it had before. I couldn't stand to put my ear to my husband's chest because his heart might stop beating while I lay there listening.

In class we learned that the American education activist Parker J. Palmer once compared death to winter, which "clears the landscape." Newcomers to the upper Midwest, he wrote, are often advised: "The winters will drive you crazy until you learn to get out into them." Walk straight ahead into winter—literal or metaphorical—or the dread of it will rule your life.

Our exercise, adapted from poet Stephen Levine's A Year to Live, was our walk into winter: We'd imagine that we were going to die in 365 days and plan the time we had left, month by month: conversations we'd like to have, things we'd longed to do.

I'd always assumed I'd...travel. I'd travel to...where? I wrote "Asia" because that covered a lot of ground. I wrote "India," and then put a question mark because it's so hot. I looked at the blank spots on the page. Filling them would have to be my homework. When I got around to it.

I'd forgotten the greatest thing about school—the feeling of possibility, that I was about to be launched into a wide world of imagination and ingenuity and beauty. Being a student again had reminded me of that expansiveness, as I made notes, asked questions, let experience—that saucy minx—be my mistress. I'd discovered that the wide world had been there all along, right where I had left it. And I considered that lesson enough.