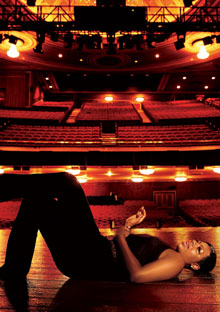

Photo: Timothy White

She once was lost, a single mother living on welfare. Then, Fantasia Barrino found the faith to rise above her situation and take a long shot: an open call for American Idol. That led to two albums, one memoir, and spectacular success as the star of The Color Purple—proof that the American Dream is alive and well and living on Broadway.

Three years ago, Fantasia Barrino—then a 19-year-old single mother surviving on food stamps in the projects of High Point, North Carolina—arrived at the Georgia Dome in Atlanta with 50 borrowed dollars and an unlikely dream: becoming the next American Idol. Not that she didn't have the talent. At the age of 5, Fantasia, then the youngest of three children and the only daughter, was already mesmerizing churchgoers with her performances as part of the Barrino Family, a gospel group formed by her father, Joseph; her mother, Diane, wrote their songs. But as the group became more successful, Fantasia's schoolwork suffered. At 14 she dropped out of high school and moved out; at 17 she became pregnant. Unable to get a job, she went on welfare. Her story could have ended there; so many others have. But something in Fantasia refused to accept that this was all her life—and her daughter Zion's life—would be. One night she watched Ruben Studdard win the second season of American Idol, and something ignited inside her. A few weeks later, Fantasia was on her way to an open call for the show. She was among the few chosen from thousands of hopefuls, and as her fellow contestants were voted off week after week, she remained. On the final episode, Fantasia put everything she had left in her heart into a song called "I Believe." That night more than 60 million viewers lit up the phone lines to vote, and Fantasia became the third American Idol. That was just the beginning. Since then she's released two albums, Free Yourself and Fantasia; written a book, Life Is Not a Fairy Tale; and watched her life story be made into a TV movie. Her most recent victory was taking on the role of Celie in the Broadway musical The Color Purple.

Since I discovered Alice Walker's novel years ago, I've loved this story of the triumph of the spirit in all its forms—as a book (it remains one of my favorites), a movie (I played Sofia), and a Broadway musical (I co-produced it). Yet when I saw Fantasia's transformative performance, I experienced this work in a completely new way. Fantasia—a rape survivor who is every bit as victorious over adversity as Celie—fully embodies the character. By the end, there is not a dry eye in the house as she sings Celie's famous refrain: "I'm beautiful, and I'm here."

Oprah: When did you first realize that you had a voice that could move people?

Fantasia: I've been singing in church since I was little; my grandmother is a pastor. When I was about 9, an elderly woman came up to me, crying, and said, "I want you to know that you touched me." My mother later told me that God had given me a gift, but I had low self-esteem. I seemed so different from other kids; I grew up in church and felt a connection with God, and a lot of kids my age really didn't understand that.

Oprah: We've all heard the story that you once couldn't read very well. Were you having problems in school?

Fantasia: Our family made two gospel albums that were pretty successful, and we were out on the road a lot, so I missed classes. When I realized I was having trouble reading, I was too embarrassed to ask for help. Some teachers believed in me, but I just wasn't focused on school—I was into the music and trying to please my dad.

Oprah: When you were growing up, did you ever feel pretty?

Fantasia: No. I got picked on because my lips were so big—my head just recently caught up with them! I'm going through this with my daughter now; she's 5 years old, and she wants to look a certain way—she wants hair or skin like somebody else at school. I say, "Zion, you're beautiful," but when my mama tried to tell me that, I didn't want to hear it. When I was a teenager, all the other girls were getting attention, but I had this skinny little body with no shape. I thought, "Maybe if I show off some leg, the guys will look at me," so I tried to get attention with tight little dresses and miniskirts.

Oprah: You were raped in high school. Can you tell me how it happened?

Fantasia: I had a crush on this guy. He was the best ballplayer, and all the girls wanted him. I thought I had no chance with him. One day during a game after school, I was flaunting around in an itty-bitty dress. I was flirting, and he told me, "You're going to get something you don't want." And that's exactly what happened.

Oprah: He raped you at school?

Fantasia: Yes. I went home and threw away my clothes. I didn't tell my mama because I thought she would say, "I told you so." I just lay on my bed, and I didn't go to school for a couple of days. My mom came to me and said, "Something's not right with you. I know that somebody put his hands on you." That's when I knew I had her support. We turned the guy in, but going back to school was hell; his homeboys would say, "I'm going to do to you exactly what he did." They thought it was funny. That's when I quit school.

Oprah: How old were you?

Fantasia: I was about 14. I got a cheap apartment in the ghetto, and a boy I'd been dating moved in. That's when the fighting began; this guy was no good for me.

Oprah: When did you get pregnant?

Fantasia: When I was 17. That's when everybody seemed to give up on me. I was the girl who could sing and was supposed to grow up and do something with my life. But when I moved out, started hanging out with the wrong people, and got pregnant, people were like, "She ain't goin' nowhere now." I'd lost myself.

Oprah: I was an adult before I understood how sexual violation was directly related to the search for love through sexual connection. Have you realized that?

Fantasia: Yes. I messed up a lot of relationships because I believed that sex means love. I want real love.

Oprah: Your grandmother is a pastor, your mother is an evangelist. What was it like for you to have to tell your family that you were pregnant at 17?

Fantasia: My grandmother already knew—she came into my room and said, "You're pregnant." I said, "No, ma'am," but she told my mother I had to see a doctor. I did, and he confirmed it. My mother was heartbroken. She and my grandmother had both gotten pregnant at 17, and they'd wanted something different for me. This was like a family curse.

Oprah: It's not a curse. It's a family cycle. And you can break that cycle with knowledge, which gives you power. That is why you must insist on an education for your daughter. When you know better, you do better.

Fantasia: That's true.

Fantasia: No. I got picked on because my lips were so big—my head just recently caught up with them! I'm going through this with my daughter now; she's 5 years old, and she wants to look a certain way—she wants hair or skin like somebody else at school. I say, "Zion, you're beautiful," but when my mama tried to tell me that, I didn't want to hear it. When I was a teenager, all the other girls were getting attention, but I had this skinny little body with no shape. I thought, "Maybe if I show off some leg, the guys will look at me," so I tried to get attention with tight little dresses and miniskirts.

Oprah: You were raped in high school. Can you tell me how it happened?

Fantasia: I had a crush on this guy. He was the best ballplayer, and all the girls wanted him. I thought I had no chance with him. One day during a game after school, I was flaunting around in an itty-bitty dress. I was flirting, and he told me, "You're going to get something you don't want." And that's exactly what happened.

Oprah: He raped you at school?

Fantasia: Yes. I went home and threw away my clothes. I didn't tell my mama because I thought she would say, "I told you so." I just lay on my bed, and I didn't go to school for a couple of days. My mom came to me and said, "Something's not right with you. I know that somebody put his hands on you." That's when I knew I had her support. We turned the guy in, but going back to school was hell; his homeboys would say, "I'm going to do to you exactly what he did." They thought it was funny. That's when I quit school.

Oprah: How old were you?

Fantasia: I was about 14. I got a cheap apartment in the ghetto, and a boy I'd been dating moved in. That's when the fighting began; this guy was no good for me.

Oprah: When did you get pregnant?

Fantasia: When I was 17. That's when everybody seemed to give up on me. I was the girl who could sing and was supposed to grow up and do something with my life. But when I moved out, started hanging out with the wrong people, and got pregnant, people were like, "She ain't goin' nowhere now." I'd lost myself.

Oprah: I was an adult before I understood how sexual violation was directly related to the search for love through sexual connection. Have you realized that?

Fantasia: Yes. I messed up a lot of relationships because I believed that sex means love. I want real love.

Oprah: Your grandmother is a pastor, your mother is an evangelist. What was it like for you to have to tell your family that you were pregnant at 17?

Fantasia: My grandmother already knew—she came into my room and said, "You're pregnant." I said, "No, ma'am," but she told my mother I had to see a doctor. I did, and he confirmed it. My mother was heartbroken. She and my grandmother had both gotten pregnant at 17, and they'd wanted something different for me. This was like a family curse.

Oprah: It's not a curse. It's a family cycle. And you can break that cycle with knowledge, which gives you power. That is why you must insist on an education for your daughter. When you know better, you do better.

Fantasia: That's true.

Photo: Timothy White

Oprah: Did you feel like your life was over once you got pregnant?

Fantasia: That's what everybody made it seem like. I knew I couldn't just get a job in a store, because I wasn't good at counting, and I didn't want to mess up anybody's money. And every time I tried to fill out an application, I wouldn't finish it because I wasn't a strong enough reader. My only plan was to sing.

Oprah: When was the first time you saw American Idol?

Fantasia: My daughter was about 2, and I was living with a man who took good care of us. I had been in abusive relationships with constant fighting and black eyes, but this man taught me that abuse wasn't love. He told me I was beautiful. Anyway, I remember all my friends talking about the show, but I never watched until the episode Ruben Studdard won. I just cried and cried.

Oprah: For him or for yourself?

Fantasia: Both. I had given up on myself. I was crying because someone had finally gotten something he wanted. I was also a little angry: Why am I sitting here in the ghetto, living on food stamps and a tiny government check? I'll be honest: Those checks just weren't enough, and I had to steal what I needed—diapers, milk, food. Some of the girls I hung out with, dated guys who were drug dealers. They had the money to provide for their children, and they would brag about what they had. At Christmas I stole a couple of educational toys for Zion because I didn't want her to turn out like me—I tried to teach her everything I could. Even now I want to get all the education I can so that when she gets home from school, I can help her with her homework. But living like that was hard.

Oprah: It's designed to be hard. It's not the government's job to break the cycle of educational impoverishment; that's your responsibility. If it was easy, you might still be in that situation.

Fantasia: It's true. After I saw Ruben win, that's when I thought, "Okay, I've got to do something." I found out that the next auditions were in Atlanta. I didn't have money or a car, so my grandmother and aunt gave me about $50 and filled up the gas tank of my brother Rico's Oldsmobile. People in High Point started talking: "I think that Fantasia girl is tryin' to sing again." I felt like I was coming back; I had faith again.

Oprah: So when you got to the audition at the Georgia Dome—I love this part of your story—the place is flooded with potential contestants…

Fantasia: There were thousands of people! I couldn't believe there were so many singers in the world. After I made it past the first round, one of the security guards—a sweet old black man—called me over and we talked and laughed as if we'd known each other forever. He said, "You're going to make it through." I had my doubts, but he kept reassuring me. Rico and I were up at 6 the next morning, but when we got there, the doors were already locked. About a hundred of us were outside, but the security guards told us to go home. While everyone else was cussing and fussing, I prayed like I ain't never prayed before! But they didn't let us in. We cried on the way to our cousin's house, where we were staying. We called home, and everyone said, "You go back there!" So we did. Everyone else was gone, but just then, the security guard I'd met the day before walked by. I told him what happened, and he went inside and came back with an American Idol assistant, who got me in. Out of more than 40,000 people, I was the last person to audition. I've never seen that security guard again, never even knew his name. I talk about him in interviews, thinking he'll pop up and say, "That was me." He never has.

Oprah: He was your angel, honey. You've said the experience restored your hope.

Fantasia: That's what everybody made it seem like. I knew I couldn't just get a job in a store, because I wasn't good at counting, and I didn't want to mess up anybody's money. And every time I tried to fill out an application, I wouldn't finish it because I wasn't a strong enough reader. My only plan was to sing.

Oprah: When was the first time you saw American Idol?

Fantasia: My daughter was about 2, and I was living with a man who took good care of us. I had been in abusive relationships with constant fighting and black eyes, but this man taught me that abuse wasn't love. He told me I was beautiful. Anyway, I remember all my friends talking about the show, but I never watched until the episode Ruben Studdard won. I just cried and cried.

Oprah: For him or for yourself?

Fantasia: Both. I had given up on myself. I was crying because someone had finally gotten something he wanted. I was also a little angry: Why am I sitting here in the ghetto, living on food stamps and a tiny government check? I'll be honest: Those checks just weren't enough, and I had to steal what I needed—diapers, milk, food. Some of the girls I hung out with, dated guys who were drug dealers. They had the money to provide for their children, and they would brag about what they had. At Christmas I stole a couple of educational toys for Zion because I didn't want her to turn out like me—I tried to teach her everything I could. Even now I want to get all the education I can so that when she gets home from school, I can help her with her homework. But living like that was hard.

Oprah: It's designed to be hard. It's not the government's job to break the cycle of educational impoverishment; that's your responsibility. If it was easy, you might still be in that situation.

Fantasia: It's true. After I saw Ruben win, that's when I thought, "Okay, I've got to do something." I found out that the next auditions were in Atlanta. I didn't have money or a car, so my grandmother and aunt gave me about $50 and filled up the gas tank of my brother Rico's Oldsmobile. People in High Point started talking: "I think that Fantasia girl is tryin' to sing again." I felt like I was coming back; I had faith again.

Oprah: So when you got to the audition at the Georgia Dome—I love this part of your story—the place is flooded with potential contestants…

Fantasia: There were thousands of people! I couldn't believe there were so many singers in the world. After I made it past the first round, one of the security guards—a sweet old black man—called me over and we talked and laughed as if we'd known each other forever. He said, "You're going to make it through." I had my doubts, but he kept reassuring me. Rico and I were up at 6 the next morning, but when we got there, the doors were already locked. About a hundred of us were outside, but the security guards told us to go home. While everyone else was cussing and fussing, I prayed like I ain't never prayed before! But they didn't let us in. We cried on the way to our cousin's house, where we were staying. We called home, and everyone said, "You go back there!" So we did. Everyone else was gone, but just then, the security guard I'd met the day before walked by. I told him what happened, and he went inside and came back with an American Idol assistant, who got me in. Out of more than 40,000 people, I was the last person to audition. I've never seen that security guard again, never even knew his name. I talk about him in interviews, thinking he'll pop up and say, "That was me." He never has.

Oprah: He was your angel, honey. You've said the experience restored your hope.

Fantasia: Yes, but I had a hard time in the beginning of the show. Some of the voters didn't like the fact that I had dropped out of school and had a baby out of wedlock. How could I be a role model for their kids? Also, I had no money for clothes to wear onstage. I felt like I didn't belong in this fancy competition with all these people who could go shopping when they wanted. I knew that if they didn't make it, they would have something else to do with their lives. This was all I had.

Oprah: In your book you wrote, "I just kept wearin' my same pair of tight jeans with different tops and different big hoop earrings and matching high heel shoes. But when I sang, I just sang from my heart and my voice probably sounded better than those jeans looked…I knew whatever happened it was gonna be okay." I love that.

Fantasia: The person I was rooming with offered to buy me some clothes, but I didn't want to feel like a charity case. I thought, "They're not looking at my clothes, and I'm going to sing like I ain't never sang before."

Oprah: At the beginning of the competition, you were just happy to be participating. When did you start wanting to win?

Fantasia: I never allowed myself to want that because I was scared of the disappointment. I thought, "Even if I don't win, I feel like a winner because I've come this far; whoever wins, God bless, and if I don't, I can still get a record deal."

Oprah: But there was a shift the night you performed your unforgettable rendition of the George Gershwin song "Summertime."

Fantasia: That was the night that everything changed. People came up to me and said, "I wasn't voting for you at first, but I have no other choice now, baby." That night, I wanted to be pure. I wanted the world to hear me cry out [sings]: "One of these mornings, y'all gonna rise up singing, then you'll spread your wings, and fly to the sky." I wanted people to see me, to change their minds about me. And that night, they did.

Oprah: A few weeks later, what did it feel like to be one of the last two singers standing?

Fantasia: It was between me and Diana DeGarmo, and I didn't think they were going to give it to me. But by that time it didn't matter; I had made it to the top two, out of all of those people. Little ol' 'Tasia, the girl everyone gave up on. The one who dropped out of school. The one who had the baby at 17. When I was announced as the winner, I fell into Diana's arms and hugged her so hard that my bracelet, my necklace, and my heel broke. It was as if the chains of bondage had finally been removed from my life.

Oprah: Let's move from one stage to another: What did you think when you were approached to perform in The Color Purple?

Fantasia: I didn't think I could do it. My manager took me to see the show and said that two men wanted to meet with me. They turned out to be Scott Sanders and Gary Griffin [the show's producer and director], and Scott pulled out a picture of the marquee with my name on it and said, "I want you to be Celie." But I was scared. For days, I thought and prayed, and I finally decided to try it. On opening night, I thought, "I've got to do my best for all the people who've come to see the show." When the crowd applauded during my first lines, I knew they wanted to see me do good, and I thought, "I can do this."

Oprah: In your book you wrote, "I just kept wearin' my same pair of tight jeans with different tops and different big hoop earrings and matching high heel shoes. But when I sang, I just sang from my heart and my voice probably sounded better than those jeans looked…I knew whatever happened it was gonna be okay." I love that.

Fantasia: The person I was rooming with offered to buy me some clothes, but I didn't want to feel like a charity case. I thought, "They're not looking at my clothes, and I'm going to sing like I ain't never sang before."

Oprah: At the beginning of the competition, you were just happy to be participating. When did you start wanting to win?

Fantasia: I never allowed myself to want that because I was scared of the disappointment. I thought, "Even if I don't win, I feel like a winner because I've come this far; whoever wins, God bless, and if I don't, I can still get a record deal."

Oprah: But there was a shift the night you performed your unforgettable rendition of the George Gershwin song "Summertime."

Fantasia: That was the night that everything changed. People came up to me and said, "I wasn't voting for you at first, but I have no other choice now, baby." That night, I wanted to be pure. I wanted the world to hear me cry out [sings]: "One of these mornings, y'all gonna rise up singing, then you'll spread your wings, and fly to the sky." I wanted people to see me, to change their minds about me. And that night, they did.

Oprah: A few weeks later, what did it feel like to be one of the last two singers standing?

Fantasia: It was between me and Diana DeGarmo, and I didn't think they were going to give it to me. But by that time it didn't matter; I had made it to the top two, out of all of those people. Little ol' 'Tasia, the girl everyone gave up on. The one who dropped out of school. The one who had the baby at 17. When I was announced as the winner, I fell into Diana's arms and hugged her so hard that my bracelet, my necklace, and my heel broke. It was as if the chains of bondage had finally been removed from my life.

Oprah: Let's move from one stage to another: What did you think when you were approached to perform in The Color Purple?

Fantasia: I didn't think I could do it. My manager took me to see the show and said that two men wanted to meet with me. They turned out to be Scott Sanders and Gary Griffin [the show's producer and director], and Scott pulled out a picture of the marquee with my name on it and said, "I want you to be Celie." But I was scared. For days, I thought and prayed, and I finally decided to try it. On opening night, I thought, "I've got to do my best for all the people who've come to see the show." When the crowd applauded during my first lines, I knew they wanted to see me do good, and I thought, "I can do this."

Oprah: That was the first play you'd ever seen, and now you're starring in it. When the little girl from High Point who didn't like her lips or her body or herself sings, "I'm beautiful and I'm here"—how does it feel?

Fantasia: I feel like Celie. Every night when I sing those words, I always break down; I'm talking to myself. I finally feel pretty. I want my own daughter to live by those words. One night, after Zion had seen the show, she said, "Were you singing to me?" I said, "Yes—because you are beautiful."

Oprah: I want Celie's song to become the anthem of women everywhere. Do you have a vision for your life beyond The Color Purple?

Fantasia: I want to still be singing at 70 years old. I want to be open to the dreams I haven't even dreamed up, because I never thought I'd be on Broadway! Every night when I play Celie, I feel myself growing up. Now I do things I never would've done before: I listen to jazz, light candles, read books—and I didn't used to like reading! I am becoming a woman.

Oprah: What has it been like to go from living in the projects to having such a big life?

Fantasia: Crazy! When I was a child, I used to dream about being onstage in front of thousands of people, and it happened. It's not about the fame; it's about people being touched. One night a 70-year-old woman came up to me after the show and told me she'd also been a single mother who had dropped out of school, and now she's taking nursing classes. She said, "You inspired me." You can't tell me that dreams don't come true. My life is proof that they do.

Fantasia: I feel like Celie. Every night when I sing those words, I always break down; I'm talking to myself. I finally feel pretty. I want my own daughter to live by those words. One night, after Zion had seen the show, she said, "Were you singing to me?" I said, "Yes—because you are beautiful."

Oprah: I want Celie's song to become the anthem of women everywhere. Do you have a vision for your life beyond The Color Purple?

Fantasia: I want to still be singing at 70 years old. I want to be open to the dreams I haven't even dreamed up, because I never thought I'd be on Broadway! Every night when I play Celie, I feel myself growing up. Now I do things I never would've done before: I listen to jazz, light candles, read books—and I didn't used to like reading! I am becoming a woman.

Oprah: What has it been like to go from living in the projects to having such a big life?

Fantasia: Crazy! When I was a child, I used to dream about being onstage in front of thousands of people, and it happened. It's not about the fame; it's about people being touched. One night a 70-year-old woman came up to me after the show and told me she'd also been a single mother who had dropped out of school, and now she's taking nursing classes. She said, "You inspired me." You can't tell me that dreams don't come true. My life is proof that they do.