Editor's note: We, along with the rest of the world, were deeply saddened to learn of Nelson Mandela's passing. The following is from an interview with O magazine in 2001.

Photo: Louise Gubb

Start reading Oprah's interview with Nelson Mandela

This is a moment I will never forget: Nelson Mandela, a man sentenced to life in prison because of his fight to end segregation in South Africa, walking away free after 27 years. As I watched him emerge from a car that day in 1990, I felt what many around the world did—overwhelming hope and joy. That Mandela survived was a testament to the power of the human spirit to overcome anything.

A few years later I had the honor of meeting Mandela in person—and just sitting in the same room with him was like being in the presence of both grace and royalty. Even now, I can hardly believe that after living in a cell for nearly three decades, he is unscathed by bitterness. He is heralded as a legend around the world because of his brave stand for freedom, yet what's even more amazing is that he allowed none of the indignities he withstood to turn his heart cold.

He could have become vengeful—easily. Born a member of the Madiba clan, Mandela spent his early years in Qunu (pronounced koo-noo). At the age of 9, after his father's death, he was sent away to be raised by the tribal king. But when he moved to Johannesburg as a 23-year-old in the 1940s, he met with the humiliation of white oppression. Under the system of racial segregation called apartheid, South Africans were required to classify themselves as white, Bantu (all black), colored (those of mixed race), or Asian. Blacks could not vote, own property, marry whites, work in white-only jobs, or travel through restricted areas without carrying a passbook. Eventually, nine million blacks were stripped of their homes and jobs as they were forced to relocate to designated "homelands"—outlying areas to which the government banished them, to ensure they'd never be citizens of South Africa.

The injustice infuriated Mandela—and catapulted him into action. In his twenties, he joined an antiapartheid group, the African National Congress (ANC), and, with his colleague Oliver Tambo, opened the country's first black law firm. He married Evelyn Mase, a nurse, and had four children, but by 1957 his commitment to the struggle for freedom overwhelmed his home life and he divorced. The next year he married Winnie Madikizela, with whom he eventually had two daughters.

After the police killed 69 blacks during a peaceful demonstration in Sharpeville, Mandela, who'd become one of South Africa's most wanted men, was forced to leave his family and take his work underground. He and his comrades endorsed an armed struggle of their own—one that targeted government offices and symbols of apartheid, not people.

Mandela fled his country to travel in Africa and Europe, and when he returned he was arrested and ultimately charged with treason. During his trial, he showed remarkable courage, donning tribal dress and saying: "I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society.... If needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die." At 46, in the winter of 1964, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison at Robben Island, South Africa's Alcatraz.

Next: How his prison stay changed everything

This is a moment I will never forget: Nelson Mandela, a man sentenced to life in prison because of his fight to end segregation in South Africa, walking away free after 27 years. As I watched him emerge from a car that day in 1990, I felt what many around the world did—overwhelming hope and joy. That Mandela survived was a testament to the power of the human spirit to overcome anything.

A few years later I had the honor of meeting Mandela in person—and just sitting in the same room with him was like being in the presence of both grace and royalty. Even now, I can hardly believe that after living in a cell for nearly three decades, he is unscathed by bitterness. He is heralded as a legend around the world because of his brave stand for freedom, yet what's even more amazing is that he allowed none of the indignities he withstood to turn his heart cold.

He could have become vengeful—easily. Born a member of the Madiba clan, Mandela spent his early years in Qunu (pronounced koo-noo). At the age of 9, after his father's death, he was sent away to be raised by the tribal king. But when he moved to Johannesburg as a 23-year-old in the 1940s, he met with the humiliation of white oppression. Under the system of racial segregation called apartheid, South Africans were required to classify themselves as white, Bantu (all black), colored (those of mixed race), or Asian. Blacks could not vote, own property, marry whites, work in white-only jobs, or travel through restricted areas without carrying a passbook. Eventually, nine million blacks were stripped of their homes and jobs as they were forced to relocate to designated "homelands"—outlying areas to which the government banished them, to ensure they'd never be citizens of South Africa.

The injustice infuriated Mandela—and catapulted him into action. In his twenties, he joined an antiapartheid group, the African National Congress (ANC), and, with his colleague Oliver Tambo, opened the country's first black law firm. He married Evelyn Mase, a nurse, and had four children, but by 1957 his commitment to the struggle for freedom overwhelmed his home life and he divorced. The next year he married Winnie Madikizela, with whom he eventually had two daughters.

After the police killed 69 blacks during a peaceful demonstration in Sharpeville, Mandela, who'd become one of South Africa's most wanted men, was forced to leave his family and take his work underground. He and his comrades endorsed an armed struggle of their own—one that targeted government offices and symbols of apartheid, not people.

Mandela fled his country to travel in Africa and Europe, and when he returned he was arrested and ultimately charged with treason. During his trial, he showed remarkable courage, donning tribal dress and saying: "I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society.... If needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die." At 46, in the winter of 1964, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison at Robben Island, South Africa's Alcatraz.

Next: How his prison stay changed everything

Even strenuous labor in the lime quarries and unrelenting isolation didn't break Mandela's spirit. During his long years in a cell barely large enough for sleeping, Mandela lost his eldest son and his mother—and wasn't allowed to attend either funeral. His wife, Winnie, who fought to keep his name alive, was often arrested and beaten. Yet from his first hours of confinement, he demanded that the prison guards respect him and refer to him only as Mandela or Mr. Mandela. As he and his comrades worked side by side in the quarries, he encouraged them to read and study, and he himself devoured books because he wanted what he believed to be freedom's most powerful weapon: education. In 1985, after more than two decades in prison, Mandela shocked the world when he rejected an offer to be released if he would renounce violence. His reason for declining: He refused to leave prison under conditions—and he would not allow himself to be singled out from the men who'd worked alongside him.

But Mandela was indeed singled out when government officials moved him to private quarters in another prison in 1988 so they could hold private negotiations for his release. Responding to the international campaign to free Mandela that had erupted in the 1980s, then-president F.W. de Klerk finally announced to Parliament on February 2, 1990, that he would lift the ban on the ANC and release the man whose long imprisonment had made him a mythical figure. Nine days later, on February 11, as millions around the world looked on in elation and disbelief, Mandela passed through the prison gates a free man.

Yet soon after Mandela's release, tribal and racial violence flared up, in part because whites rebuffed efforts for a free election. In 1992, with the death toll climbing, Mandela met with de Klerk, hoping to ward off a civil war; in the following months he urged South Africans to seek not revenge but reconciliation. For their efforts to unite the country, Mandela and de Klerk were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. They accepted the award jointly. The next year, people of every race were allowed, for the first time, to vote in a democratic election. For four days, millions of blacks lined up across South Africa to exercise the right for which Mandela had been willing to give his life. A candidate himself, Mandela cast his vote, something he later told reporters made him feel like a "complete man." After a landslide victory, Mandela became South Africa's leader—and he appointed de Klerk his deputy president.

As Mandela's political career reached its height, his marriage crashed. Nearly 30 years of separation from Winnie were too taxing a burden on their relationship. In 1992, amid reports of his wife's infidelity and political scandals, Mandela made one of the toughest choices of his life: to leave Winnie. "To part with a lady with whom you had enjoyed some of the best moments in life, who had suffered and worked hard for your liberation and who had given you two beautiful children—that was not an easy decision," he later told me. After an intense period of grieving and isolation, he found love again in Graça Machel, the widow of Mozambique's founding president, Samora Machel. In a secret ceremony on Mandela's 80th birthday, Graça gave Mandela what she called a present: her hand in marriage. The next day, at an extravagant birthday bash filled with celebrities from around the world, Mandela introduced his bride.

Next: Oprah visits Nelson Mandela at home

But Mandela was indeed singled out when government officials moved him to private quarters in another prison in 1988 so they could hold private negotiations for his release. Responding to the international campaign to free Mandela that had erupted in the 1980s, then-president F.W. de Klerk finally announced to Parliament on February 2, 1990, that he would lift the ban on the ANC and release the man whose long imprisonment had made him a mythical figure. Nine days later, on February 11, as millions around the world looked on in elation and disbelief, Mandela passed through the prison gates a free man.

Yet soon after Mandela's release, tribal and racial violence flared up, in part because whites rebuffed efforts for a free election. In 1992, with the death toll climbing, Mandela met with de Klerk, hoping to ward off a civil war; in the following months he urged South Africans to seek not revenge but reconciliation. For their efforts to unite the country, Mandela and de Klerk were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. They accepted the award jointly. The next year, people of every race were allowed, for the first time, to vote in a democratic election. For four days, millions of blacks lined up across South Africa to exercise the right for which Mandela had been willing to give his life. A candidate himself, Mandela cast his vote, something he later told reporters made him feel like a "complete man." After a landslide victory, Mandela became South Africa's leader—and he appointed de Klerk his deputy president.

As Mandela's political career reached its height, his marriage crashed. Nearly 30 years of separation from Winnie were too taxing a burden on their relationship. In 1992, amid reports of his wife's infidelity and political scandals, Mandela made one of the toughest choices of his life: to leave Winnie. "To part with a lady with whom you had enjoyed some of the best moments in life, who had suffered and worked hard for your liberation and who had given you two beautiful children—that was not an easy decision," he later told me. After an intense period of grieving and isolation, he found love again in Graça Machel, the widow of Mozambique's founding president, Samora Machel. In a secret ceremony on Mandela's 80th birthday, Graça gave Mandela what she called a present: her hand in marriage. The next day, at an extravagant birthday bash filled with celebrities from around the world, Mandela introduced his bride.

Next: Oprah visits Nelson Mandela at home

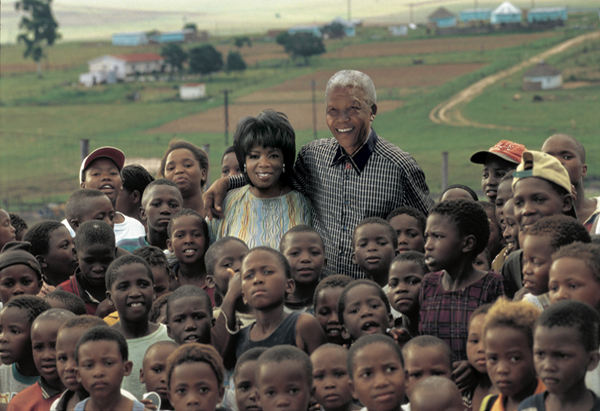

It is in the couple's home, with the hills of Qunu in the background, that I again meet with my dear friend. I have made the trip from Chicago to South Africa because I want to better understand what Mandela has lived through. (A few days before our conversation, I visited Robben Island and stood in his tiny cell, trying to imagine spending years there.)

On the two-lane highway that weaves through the town where Mandela began his life 82 years ago, sheep and goats dot the green, sweeping landscape. Along dirt roads, barefoot women balance baskets on their heads, while the few men actually around—many go off for months at a time to work in the mines in Johannesburg—drag oxcarts along small plots of farmland. Most of the people still live in severe poverty and struggle to come by clean water; even the more fortunate families live in small shanty structures that often provide shelter for two or three families. I have already learned that in the neighboring African nation of Botswana, one in three adults is infected with the AIDS virus. I know that even in this small town, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, children, aunts, and uncles could not have altogether escaped the illness that is ravishing their continent.

When I finally arrive at Mandela's home, he greets me with a huge embrace— he is one of the warmest and most humble people I know. Amid kids and grandchildren who roam freely about the Mandela estate, a spirited Graça ushers me to a table set for an amazing feast: lamb stew, pork chops, seafood paella, and a traditional South African dish made with tripe. After we share the meal, Mandela settles into the corner of the couch that Graça calls his seat; from it, he can peer through a huge window overlooking most of Qunu. Here in his homeland, Mandela tells me what spending 27 years in prison taught him about himself—and why there is one thing he has never feared.

Start reading Oprah's interview with Nelson Mandela

Note: This interview appeared in the April 2001 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine.

On the two-lane highway that weaves through the town where Mandela began his life 82 years ago, sheep and goats dot the green, sweeping landscape. Along dirt roads, barefoot women balance baskets on their heads, while the few men actually around—many go off for months at a time to work in the mines in Johannesburg—drag oxcarts along small plots of farmland. Most of the people still live in severe poverty and struggle to come by clean water; even the more fortunate families live in small shanty structures that often provide shelter for two or three families. I have already learned that in the neighboring African nation of Botswana, one in three adults is infected with the AIDS virus. I know that even in this small town, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, children, aunts, and uncles could not have altogether escaped the illness that is ravishing their continent.

When I finally arrive at Mandela's home, he greets me with a huge embrace— he is one of the warmest and most humble people I know. Amid kids and grandchildren who roam freely about the Mandela estate, a spirited Graça ushers me to a table set for an amazing feast: lamb stew, pork chops, seafood paella, and a traditional South African dish made with tripe. After we share the meal, Mandela settles into the corner of the couch that Graça calls his seat; from it, he can peer through a huge window overlooking most of Qunu. Here in his homeland, Mandela tells me what spending 27 years in prison taught him about himself—and why there is one thing he has never feared.

Start reading Oprah's interview with Nelson Mandela

Note: This interview appeared in the April 2001 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine.

Photo: Louise Gubb

Oprah: The last time we talked, you said that if you hadn't been in prison, you wouldn't have achieved the most difficult task in life—changing yourself. How did 27 years of reflection make you a different man?

Nelson Mandela: Before I went to jail, I was active in politics as a member of South Africa's leading organization—and I was generally busy from 7 A.M. until midnight. I never had time to sit and think. As I worked, physical and mental fatigue set in and I was unable to operate to the maximum of my intellectual ability. But in a single cell in prison, I had time to think. I had a clear view of my past and present, and I found that my past left much to be desired, both in regard to my relations with other humans and in developing personal worth.

Oprah: In what way did your past leave much to be desired?

Nelson Mandela: When I reached Johannesburg in the 1940s, I was neglected by my family because I had disappointed them—I'd run away from being forced into an arranged marriage, which was a big blow to them. In Johannesburg, many people were kind to me—but when I finished my studies and qualified as a lawyer, I got busy with politics and never thought of them. It was only when I was in jail that I wondered, "What happened to so-and-so? Why didn't I go back and say thank you?" I had become very small and had not behaved like a human who appreciates hospitality and support. I decided that if I ever got out of prison, I would make it up to those people or to their children and grandchildren. That is how I was able to change my life—by knowing that if somebody does something good for you, you have to respond.

Oprah: All the time.

Nelson Mandela: And that is what I am doing now—responding. There is nothing I fear more than waking up without a program that will help me bring a little happiness to those with no resources, those who are poor, illiterate, and ridden with terminal disease. If there is anything that will one day kill me, it will be the inability to help them. If I can spend a tiny part of my life making them happy, I'll be happy.

Oprah: So when you wake up in the morning, your day is all about giving?

Nelson Mandela: In particular, it's about building schools, clinics, and community halls and arranging scholarships for children. And of course, I have duties to my family.

Oprah: Are you making up for all the years you weren't there to help?

Nelson Mandela: That is not uppermost in my mind, but I will use the rest of my life to help the poor overcome the problems confronting them—poverty is the greatest challenge facing humanity. That is why I build schools; I want to free people from poverty and illiteracy.

Oprah: I recently spent time at Robben Island, the prison where you lived for the first 18 years of your sentence. I heard that you saw your youngest daughters when they were 2 and 3, and then didn't see them again until they were around 16! What was that like?

Nelson Mandela: Not seeing them may be why I've developed an obsession with children—I missed seeing any for 27 years. It's one of the most severe punishments prison life can impose, because children are the most important asset in a country. For them to become that asset, they must receive education and love from their parents. And when you are in jail, you are unable to give those things to your children.

Next: His greatest loss

Nelson Mandela: Before I went to jail, I was active in politics as a member of South Africa's leading organization—and I was generally busy from 7 A.M. until midnight. I never had time to sit and think. As I worked, physical and mental fatigue set in and I was unable to operate to the maximum of my intellectual ability. But in a single cell in prison, I had time to think. I had a clear view of my past and present, and I found that my past left much to be desired, both in regard to my relations with other humans and in developing personal worth.

Oprah: In what way did your past leave much to be desired?

Nelson Mandela: When I reached Johannesburg in the 1940s, I was neglected by my family because I had disappointed them—I'd run away from being forced into an arranged marriage, which was a big blow to them. In Johannesburg, many people were kind to me—but when I finished my studies and qualified as a lawyer, I got busy with politics and never thought of them. It was only when I was in jail that I wondered, "What happened to so-and-so? Why didn't I go back and say thank you?" I had become very small and had not behaved like a human who appreciates hospitality and support. I decided that if I ever got out of prison, I would make it up to those people or to their children and grandchildren. That is how I was able to change my life—by knowing that if somebody does something good for you, you have to respond.

Oprah: All the time.

Nelson Mandela: And that is what I am doing now—responding. There is nothing I fear more than waking up without a program that will help me bring a little happiness to those with no resources, those who are poor, illiterate, and ridden with terminal disease. If there is anything that will one day kill me, it will be the inability to help them. If I can spend a tiny part of my life making them happy, I'll be happy.

Oprah: So when you wake up in the morning, your day is all about giving?

Nelson Mandela: In particular, it's about building schools, clinics, and community halls and arranging scholarships for children. And of course, I have duties to my family.

Oprah: Are you making up for all the years you weren't there to help?

Nelson Mandela: That is not uppermost in my mind, but I will use the rest of my life to help the poor overcome the problems confronting them—poverty is the greatest challenge facing humanity. That is why I build schools; I want to free people from poverty and illiteracy.

Oprah: I recently spent time at Robben Island, the prison where you lived for the first 18 years of your sentence. I heard that you saw your youngest daughters when they were 2 and 3, and then didn't see them again until they were around 16! What was that like?

Nelson Mandela: Not seeing them may be why I've developed an obsession with children—I missed seeing any for 27 years. It's one of the most severe punishments prison life can impose, because children are the most important asset in a country. For them to become that asset, they must receive education and love from their parents. And when you are in jail, you are unable to give those things to your children.

Next: His greatest loss

Oprah: It's hard to imagine a world where you're not allowed to see, touch, or hold your own children. Was that your greatest loss?

Nelson Mandela: Absolutely.

Oprah: What else did you miss?

Nelson Mandela: My family, of course. And I missed my people. In many respects, people on the outside suffered more than those of us in jail. In prison, we ate three times a day, we had clothing, we had free medical services, and we could sleep for 12 hours. Others did not enjoy these things.

Oprah: Did you feel disconnected from the world?

Nelson Mandela: We had our ways of communicating with the outside. And though we would get the news two or three days after it had happened, we still got it. Because we became friendly with certain wardens, we'd ask them, "Can't you take us to the rubbish dump?" Newspapers were dumped there, and we'd clean them off, hide them, and take them back to our cells to read.

Oprah: You became even more disciplined in prison than you had been before, studying regularly and encouraging your colleagues to study. Why?

Nelson Mandela: No country can really develop unless its citizens are educated. Any nation that is progressive is led by people who have had the privilege of studying. I knew we could improve our lives even in jail. We could come out as different men, and we could even come out with two degrees. Educating ourselves was a way to give ourselves the most powerful weapon for freedom.

Oprah: Did you come out a wiser man?

Nelson Mandela: All I can say is that I was less foolish than I was when I went in. I equipped myself by reading literature, especially classic novels such as The Grapes of Wrath.

Oprah: That's one of my favorite books.

Nelson Mandela: When I closed that book, I was a different man. It enriched my powers of thinking and discipline, and my relationships. I left prison more informed than when I went in. And the more informed you are, the less arrogant and aggressive you are.

Oprah: Do you disdain arrogance?

Nelson Mandela: Of course. In my younger days, I was arrogant—jail helped me to get rid of it. I did nothing but make enemies because of my arrogance.

Oprah: What other characteristics do you abhor?

Nelson Mandela: Ignorance—and a person's inability to see what unites us instead of only those things that divide us. A good leader can engage in a debate frankly and thoroughly, knowing that at the end he and the other side must be closer, and thus emerge stronger. You don't have that idea when you are arrogant, superficial, and uninformed.

Next: What it takes to be a great leader

Nelson Mandela: Absolutely.

Oprah: What else did you miss?

Nelson Mandela: My family, of course. And I missed my people. In many respects, people on the outside suffered more than those of us in jail. In prison, we ate three times a day, we had clothing, we had free medical services, and we could sleep for 12 hours. Others did not enjoy these things.

Oprah: Did you feel disconnected from the world?

Nelson Mandela: We had our ways of communicating with the outside. And though we would get the news two or three days after it had happened, we still got it. Because we became friendly with certain wardens, we'd ask them, "Can't you take us to the rubbish dump?" Newspapers were dumped there, and we'd clean them off, hide them, and take them back to our cells to read.

Oprah: You became even more disciplined in prison than you had been before, studying regularly and encouraging your colleagues to study. Why?

Nelson Mandela: No country can really develop unless its citizens are educated. Any nation that is progressive is led by people who have had the privilege of studying. I knew we could improve our lives even in jail. We could come out as different men, and we could even come out with two degrees. Educating ourselves was a way to give ourselves the most powerful weapon for freedom.

Oprah: Did you come out a wiser man?

Nelson Mandela: All I can say is that I was less foolish than I was when I went in. I equipped myself by reading literature, especially classic novels such as The Grapes of Wrath.

Oprah: That's one of my favorite books.

Nelson Mandela: When I closed that book, I was a different man. It enriched my powers of thinking and discipline, and my relationships. I left prison more informed than when I went in. And the more informed you are, the less arrogant and aggressive you are.

Oprah: Do you disdain arrogance?

Nelson Mandela: Of course. In my younger days, I was arrogant—jail helped me to get rid of it. I did nothing but make enemies because of my arrogance.

Oprah: What other characteristics do you abhor?

Nelson Mandela: Ignorance—and a person's inability to see what unites us instead of only those things that divide us. A good leader can engage in a debate frankly and thoroughly, knowing that at the end he and the other side must be closer, and thus emerge stronger. You don't have that idea when you are arrogant, superficial, and uninformed.

Next: What it takes to be a great leader

Oprah: You just want your point of view to prevail. But a good leader always has the intention of making peace.

Nelson Mandela: That's true. When there is danger, a good leader takes the front line; but when there is celebration, a good leader stays in the back of the room.

Oprah: What characteristics do you most admire in those you respect?

Nelson Mandela: Sometimes a leader has to criticize those with whom he works—it cannot be avoided. I like a leader who can, while pointing out a mistake, bring up the good things the other person has done. If you do that, then the person sees that you have a complete picture of him. There is nobody more dangerous than one who has been humiliated, even when you humiliate him rightly.

Oprah: As I sit here and talk with you, I find it hard to imagine that you can be the man you are after spending all that time in a seven-by-nine-foot cell. When you went back to see the cell years later, could you believe it was that tiny?

Nelson Mandela: Back then I was used to it, and I could do all sorts of things in there, like exercise every morning and evening. But now that I'm on the outside, I don't know how we survived it—the space was so small.

Oprah: During the day, when you were forced to do hard labor in the lime quarries, you also had the chance to talk with your colleagues. But when I visited the prison I was told that at 4 P.M. each day, the cell doors were closed and you weren't allowed to speak.

Nelson Mandela: That's true, but we challenged that rule. The officers who were senior to the wardens treated them like vermin, but because we treated the wardens with respect, they helped us. Once the cells were locked and the senior officers went away, the wardens allowed us to do anything except open the cell doors, because they didn't have keys. They let us speak to those in the cells opposite us. As a result of the way we treated the wardens, they tended to become good people.

Oprah: Do you believe people are good at their core?

Nelson Mandela: There is no doubt whatsoever, provided you are able to arouse the goodness inherent in every human. Those of us in the fight against apartheid changed many people who hated us because they discovered that we respected them.

Oprah: How can you respect people who oppress you?

Nelson Mandela: You must understand that individuals get caught up in the policy of their country. In prison, for instance, a warden or officer is not promoted if he doesn't follow the policy of the government—though he himself does not believe in that policy.

Oprah: So you can change someone who is only carrying out a policy, since that person himself isn't the policy.

Nelson Mandela: Absolutely. When I went to jail, I was a trained lawyer. And when the wardens received letters of demands or summonses, they didn't have the resources to go to an attorney to help them. I would help them settle their cases, so they became attached to me and the other prisoners.

Next: The secret to defeating any opponent

Nelson Mandela: That's true. When there is danger, a good leader takes the front line; but when there is celebration, a good leader stays in the back of the room.

Oprah: What characteristics do you most admire in those you respect?

Nelson Mandela: Sometimes a leader has to criticize those with whom he works—it cannot be avoided. I like a leader who can, while pointing out a mistake, bring up the good things the other person has done. If you do that, then the person sees that you have a complete picture of him. There is nobody more dangerous than one who has been humiliated, even when you humiliate him rightly.

Oprah: As I sit here and talk with you, I find it hard to imagine that you can be the man you are after spending all that time in a seven-by-nine-foot cell. When you went back to see the cell years later, could you believe it was that tiny?

Nelson Mandela: Back then I was used to it, and I could do all sorts of things in there, like exercise every morning and evening. But now that I'm on the outside, I don't know how we survived it—the space was so small.

Oprah: During the day, when you were forced to do hard labor in the lime quarries, you also had the chance to talk with your colleagues. But when I visited the prison I was told that at 4 P.M. each day, the cell doors were closed and you weren't allowed to speak.

Nelson Mandela: That's true, but we challenged that rule. The officers who were senior to the wardens treated them like vermin, but because we treated the wardens with respect, they helped us. Once the cells were locked and the senior officers went away, the wardens allowed us to do anything except open the cell doors, because they didn't have keys. They let us speak to those in the cells opposite us. As a result of the way we treated the wardens, they tended to become good people.

Oprah: Do you believe people are good at their core?

Nelson Mandela: There is no doubt whatsoever, provided you are able to arouse the goodness inherent in every human. Those of us in the fight against apartheid changed many people who hated us because they discovered that we respected them.

Oprah: How can you respect people who oppress you?

Nelson Mandela: You must understand that individuals get caught up in the policy of their country. In prison, for instance, a warden or officer is not promoted if he doesn't follow the policy of the government—though he himself does not believe in that policy.

Oprah: So you can change someone who is only carrying out a policy, since that person himself isn't the policy.

Nelson Mandela: Absolutely. When I went to jail, I was a trained lawyer. And when the wardens received letters of demands or summonses, they didn't have the resources to go to an attorney to help them. I would help them settle their cases, so they became attached to me and the other prisoners.

Next: The secret to defeating any opponent

Oprah: In your autobiography, you say that you understood you could defeat your opponent without dishonoring him. How did you learn that?

Nelson Mandela: My colleagues and I did not want to speak to the apartheid rulers at all, but some of us did the type of work that brought us into contact with our oppressors. For instance, when blacks were forced to leave Johannesburg and go back to their homelands, a man would come to me and say, "Help me. I have lost my job. I have a wife and children in school, and I am now required to leave my home." As a lawyer, I would go to the top authorities and say, "Look, I'm approaching you as a human, and here is my problem. I have to rely on you." Invariably, the person would allow the man to look for a job. So I discovered even before I went to jail that apartheid was not run by people who were monolithic in their approach. Some of them didn't even believe in apartheid.

If you sit down and talk to a person, it's easy to convince him that apartheid can never save a country and will lead to the slaughtering of innocent people—including his own people. So we changed the hardened apartheid rulers into people who could work with us, because we exploited their good qualities.

Oprah: You've written that when you were a boy, all the townspeople brought their problems to the regent, who listened to each person before giving his answer.

Nelson Mandela: That principle influenced me throughout my life. I learned to have the patience to listen when people put forward their views, even if I think those views are wrong. You can't reach a just decision in a dispute unless you listen to both sides, ask questions, and view the evidence placed before you. If you don't allow people to contribute, to offer their point of view, or to criticize what has been put before them, then they can never like you. And you can never build that instrument of collective leadership.

Oprah: At one point you were offered the chance to leave prison early if you renounced violence—and you chose not to. Did you believe that violence was a solution?

Nelson Mandela: No. When I was told, "You'll be released as soon as you renounce violence," I said, "You started violence—our violence is a defense. The methods of political action that oppressed people use are determined by the oppressor." And I didn't want to leave jail under conditions. I also wouldn't allow myself to be singled out from my colleagues.

Oprah: I read that you never allowed yourself to be treated better than other prisoners because you saw yourself and the men who'd worked alongside you as a collective leadership.

Nelson Mandela: Our people outside of prison used my name to mobilize the community locally and internationally. But for me to be treated separately from my colleagues, who had contributed as much as and even more than I had, would have been a betrayal of them.

Oprah: There you all were, brothers side by side who had all gone to prison at the same time—and yet much of the world knew only your name. We never knew there was a Mandela group.

Nelson Mandela: I'm not just saying this out of humility, but some of those men were more intelligent and more determined as fighters for freedom than I was.

Next: How he finally was set free

Nelson Mandela: My colleagues and I did not want to speak to the apartheid rulers at all, but some of us did the type of work that brought us into contact with our oppressors. For instance, when blacks were forced to leave Johannesburg and go back to their homelands, a man would come to me and say, "Help me. I have lost my job. I have a wife and children in school, and I am now required to leave my home." As a lawyer, I would go to the top authorities and say, "Look, I'm approaching you as a human, and here is my problem. I have to rely on you." Invariably, the person would allow the man to look for a job. So I discovered even before I went to jail that apartheid was not run by people who were monolithic in their approach. Some of them didn't even believe in apartheid.

If you sit down and talk to a person, it's easy to convince him that apartheid can never save a country and will lead to the slaughtering of innocent people—including his own people. So we changed the hardened apartheid rulers into people who could work with us, because we exploited their good qualities.

Oprah: You've written that when you were a boy, all the townspeople brought their problems to the regent, who listened to each person before giving his answer.

Nelson Mandela: That principle influenced me throughout my life. I learned to have the patience to listen when people put forward their views, even if I think those views are wrong. You can't reach a just decision in a dispute unless you listen to both sides, ask questions, and view the evidence placed before you. If you don't allow people to contribute, to offer their point of view, or to criticize what has been put before them, then they can never like you. And you can never build that instrument of collective leadership.

Oprah: At one point you were offered the chance to leave prison early if you renounced violence—and you chose not to. Did you believe that violence was a solution?

Nelson Mandela: No. When I was told, "You'll be released as soon as you renounce violence," I said, "You started violence—our violence is a defense. The methods of political action that oppressed people use are determined by the oppressor." And I didn't want to leave jail under conditions. I also wouldn't allow myself to be singled out from my colleagues.

Oprah: I read that you never allowed yourself to be treated better than other prisoners because you saw yourself and the men who'd worked alongside you as a collective leadership.

Nelson Mandela: Our people outside of prison used my name to mobilize the community locally and internationally. But for me to be treated separately from my colleagues, who had contributed as much as and even more than I had, would have been a betrayal of them.

Oprah: There you all were, brothers side by side who had all gone to prison at the same time—and yet much of the world knew only your name. We never knew there was a Mandela group.

Nelson Mandela: I'm not just saying this out of humility, but some of those men were more intelligent and more determined as fighters for freedom than I was.

Next: How he finally was set free

Oprah: In 1986 you began the negotiations that led to your release. Did you really believe you would be freed?

Nelson Mandela: We always knew that one day we would be released—we just did not know when. The prison would send a warden to say to us, "Give me your names, the places you came from, and exactly where you'd go if you were released." Sometimes the wardens would tell us, "You chaps cannot be kept, because the whole world is insisting that you be released."

There were times when the government seemed to have crushed the antiapartheid movement completely—and our spirits were down. But the dominating idea was that one day we'd get out.

When Mr. de Klerk called me [on February 10, 1990], he said, "I've decided to release you—tomorrow." I said, "You have taken me by surprise. Give me at least a week to inform our people outside so they can prepare." I also told de Klerk that once I reached the gate of the jail, he would have no control over me. I wanted to be released from the Victor Verster prison, which is where I had been held since 1988, so that I could talk with the people in that area who had looked after me. But de Klerk had intended to fly me to Pretoria, South Africa, and release me there. I refused. I had been jailed because I wanted to think for myself, so I would not let them think for me even then. They released me from Victor Verster the next day—they had already told the press of my release, and reporters had come from all over the world.

Oprah: So after 27 years of prison you said, "I will be released on my terms."

Nelson Mandela: Yes. And my fellow prisoners and I knew that the international community was supporting us.

Oprah: Is it true that when you were freed at age 71, it was like being born again?

Nelson Mandela: Yes. When I was inside the prison, I told the wardens to come to the gate with their families because I wanted to thank them. I honestly thought they would be the only people who would be at the gate! I had no idea that I would meet a huge crowd.

Oprah: You once told me that humility is one of the greatest qualities a leader can have. Did you come out of prison a more humble man?

Nelson Mandela: If you are humble, you are no threat to anybody. Some behave in a way that dominates others. That's a mistake. If you want the cooperation of humans around you, you must make them feel they are important—and you do that by being genuine and humble. You know that other people have qualities that may be better than your own. Let them express them.

Oprah: Maya Angelou says that humility is knowing your place in the world. It's understanding that you are not the first person who has ever done anything important.

Nelson Mandela: That is a truism.

Next: The family tragedy he faced during prison

Nelson Mandela: We always knew that one day we would be released—we just did not know when. The prison would send a warden to say to us, "Give me your names, the places you came from, and exactly where you'd go if you were released." Sometimes the wardens would tell us, "You chaps cannot be kept, because the whole world is insisting that you be released."

There were times when the government seemed to have crushed the antiapartheid movement completely—and our spirits were down. But the dominating idea was that one day we'd get out.

When Mr. de Klerk called me [on February 10, 1990], he said, "I've decided to release you—tomorrow." I said, "You have taken me by surprise. Give me at least a week to inform our people outside so they can prepare." I also told de Klerk that once I reached the gate of the jail, he would have no control over me. I wanted to be released from the Victor Verster prison, which is where I had been held since 1988, so that I could talk with the people in that area who had looked after me. But de Klerk had intended to fly me to Pretoria, South Africa, and release me there. I refused. I had been jailed because I wanted to think for myself, so I would not let them think for me even then. They released me from Victor Verster the next day—they had already told the press of my release, and reporters had come from all over the world.

Oprah: So after 27 years of prison you said, "I will be released on my terms."

Nelson Mandela: Yes. And my fellow prisoners and I knew that the international community was supporting us.

Oprah: Is it true that when you were freed at age 71, it was like being born again?

Nelson Mandela: Yes. When I was inside the prison, I told the wardens to come to the gate with their families because I wanted to thank them. I honestly thought they would be the only people who would be at the gate! I had no idea that I would meet a huge crowd.

Oprah: You once told me that humility is one of the greatest qualities a leader can have. Did you come out of prison a more humble man?

Nelson Mandela: If you are humble, you are no threat to anybody. Some behave in a way that dominates others. That's a mistake. If you want the cooperation of humans around you, you must make them feel they are important—and you do that by being genuine and humble. You know that other people have qualities that may be better than your own. Let them express them.

Oprah: Maya Angelou says that humility is knowing your place in the world. It's understanding that you are not the first person who has ever done anything important.

Nelson Mandela: That is a truism.

Next: The family tragedy he faced during prison

Oprah: I want to talk about what being in Qunu means to you. Do you come here often?

Nelson Mandela: As much as possible. My wife and I don't celebrate family days in Johannesburg, though we have a home there. My eldest son died in a car accident while I was in jail, and—

Oprah: And you weren't allowed to go to the funeral?

Nelson Mandela: No. We buried him in Johannesburg, but later my wife said, "That child must be buried in Qunu, next to your father." I also lost a daughter who died when she was a baby, and she was buried here. So Graça told me, "You must have a day with the family in Qunu, when you aren't running around the world. You can invite your children, your grandchildren, and your close relatives to come and bond."

Oprah: Did you ever think you could fall in love again at your age?

Nelson Mandela: When I first saw this lady, it was not a question of love. I regarded her as the wife of a president I had never met. I respected her very much.

Oprah: How has she changed you?

Nelson Mandela: Oh, very much. She is more stable than me, she does not get easily excited—and she keeps on warning me not to be overly enthusiastic in my work. She is a very good adviser, both on family issues and things of an international nature because she has traveled all over the world.

Oprah: One of the greatest lessons your life teaches us all is the power in forgiving our oppressors. As you once told me, you "made the brain dominate the blood." How were you able to practice that principle?

Nelson Mandela: We all struggled with it, especially since we were dealing with an enemy who was more powerful than us. But because we wanted to avoid slaughtering each other, we had to suppress our feelings. That is the only way to bring about a peaceful transformation.

Oprah: Many people can't even do that in their own families.

Nelson Mandela: True, but we must teach people that when they've been wronged, they must talk to their enemies and resolve their differences for the sake of peace.

Oprah: Now that you are in what you call the evening of your life, what do you most look forward to?

Nelson Mandela: I want to continue the work I'm doing. In some areas, poor people haven't had proper roads, electricity, water, or even toilets. But things are changing. The whole process will take many years.

Next: What Nelson Mandela knows for sure

Nelson Mandela: As much as possible. My wife and I don't celebrate family days in Johannesburg, though we have a home there. My eldest son died in a car accident while I was in jail, and—

Oprah: And you weren't allowed to go to the funeral?

Nelson Mandela: No. We buried him in Johannesburg, but later my wife said, "That child must be buried in Qunu, next to your father." I also lost a daughter who died when she was a baby, and she was buried here. So Graça told me, "You must have a day with the family in Qunu, when you aren't running around the world. You can invite your children, your grandchildren, and your close relatives to come and bond."

Oprah: Did you ever think you could fall in love again at your age?

Nelson Mandela: When I first saw this lady, it was not a question of love. I regarded her as the wife of a president I had never met. I respected her very much.

Oprah: How has she changed you?

Nelson Mandela: Oh, very much. She is more stable than me, she does not get easily excited—and she keeps on warning me not to be overly enthusiastic in my work. She is a very good adviser, both on family issues and things of an international nature because she has traveled all over the world.

Oprah: One of the greatest lessons your life teaches us all is the power in forgiving our oppressors. As you once told me, you "made the brain dominate the blood." How were you able to practice that principle?

Nelson Mandela: We all struggled with it, especially since we were dealing with an enemy who was more powerful than us. But because we wanted to avoid slaughtering each other, we had to suppress our feelings. That is the only way to bring about a peaceful transformation.

Oprah: Many people can't even do that in their own families.

Nelson Mandela: True, but we must teach people that when they've been wronged, they must talk to their enemies and resolve their differences for the sake of peace.

Oprah: Now that you are in what you call the evening of your life, what do you most look forward to?

Nelson Mandela: I want to continue the work I'm doing. In some areas, poor people haven't had proper roads, electricity, water, or even toilets. But things are changing. The whole process will take many years.

Next: What Nelson Mandela knows for sure

Oprah: One reason I hold you and your comrades in such high reverence is that you maintained your dignity in the face of oppression. You must be proud of yourself for that.

Nelson Mandela: You are very generous, Oprah. All I can tell you is that if I am the person you say I am, I was not always that man.

Oprah: At the end of the magazine each month, I write a column called "What I Know for Sure". What do you know for sure?

Nelson Mandela: I know that my wife will always support me. And I know that, throughout the world, there are good men and women concerned with the greatest challenges facing society today—poverty, illiteracy, and disease.

Oprah: Do you fear death?

Nelson Mandela: No. Shakespeare put it very well: "Cowards die many times before their deaths; the valiant never taste of death but once. Of all the wonders that I yet have heard, it seems to me most strange that men should fear; seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come." When you believe that, you disappear under a cloud of glory. Your name lives beyond the grave—and that is my approach.

More Inspiration from Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela: You are very generous, Oprah. All I can tell you is that if I am the person you say I am, I was not always that man.

Oprah: At the end of the magazine each month, I write a column called "What I Know for Sure". What do you know for sure?

Nelson Mandela: I know that my wife will always support me. And I know that, throughout the world, there are good men and women concerned with the greatest challenges facing society today—poverty, illiteracy, and disease.

Oprah: Do you fear death?

Nelson Mandela: No. Shakespeare put it very well: "Cowards die many times before their deaths; the valiant never taste of death but once. Of all the wonders that I yet have heard, it seems to me most strange that men should fear; seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come." When you believe that, you disappear under a cloud of glory. Your name lives beyond the grave—and that is my approach.

More Inspiration from Nelson Mandela