The Powerful Ways Poetry Shapes Our Lives

In an era of sensory overload, there is stillness and clarity to be found in verse. To commemorate National Poetry Month, we celebrate that singular form, with the help of a few leading practitioners.

By Natasha Trethewey, Laura Kasischke and Terre Roche

Illustration: Peter Oumanski

Why Poetry Matters

I was 19 when I lost my mom, but it wasn't until years later that I encountered Lisel Mueller's poem "When I Am Asked," about a day soon after her own mother died. It begins, "When I am asked / how I began writing poems, / I talk about the indifference of nature." It goes on to convey Mueller's sadness that the world seemed not to care about her loss and ends with this lovely declaration:

I sat on a gray stone bench

ringed with the ingenue faces

of pink and white impatiens

and placed my grief

in the mouth of language,

the only thing that would grieve with me.

Each time I return to these lines, I am reminded that loss is a shared, not a solo, experience. In that way, poetry makes for us the largest community; it shows us ourselves by illuminating the interior lives of others. One cannot read a poem without being aware of the poet's voice—whether loud or barely a whisper—speaking across the distances, time and space. Poems offer a form of refuge.

They can comfort us when we grieve or can celebrate joy, as in Kevin Young's "First Kick," which captures the thrill of feeling his baby's earliest movements:

More like

a flicker, a far

-off flutter

beneath my

broad hand—

then, two

weeks later,

a nudge, a knee

as you elbow round inside—

acrobat, apple

of our eye

we can't

yet see....

And poetry helps us remember—keeping alive the cultural legacy of a people. Here are the last lines of Jake Adam York's poem "Postscript," written for slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers:

Again, today, the light is new,

and because you are nowhere

you are everywhere,

in the face of which I'd ask

how can I say anything,

in the face of which I'd ask

how can I say nothing at all?

Occasions for the kind of quiet contemplation and focus that poetry seems to require are rare, and yet the need for poetry arises again and again. The act of making poetry is an act of hope.

—Natasha Trethewey, United States poet laureate from 2012 to 2014

ringed with the ingenue faces

of pink and white impatiens

and placed my grief

in the mouth of language,

the only thing that would grieve with me.

Each time I return to these lines, I am reminded that loss is a shared, not a solo, experience. In that way, poetry makes for us the largest community; it shows us ourselves by illuminating the interior lives of others. One cannot read a poem without being aware of the poet's voice—whether loud or barely a whisper—speaking across the distances, time and space. Poems offer a form of refuge.

They can comfort us when we grieve or can celebrate joy, as in Kevin Young's "First Kick," which captures the thrill of feeling his baby's earliest movements:

a flicker, a far

-off flutter

beneath my

broad hand—

then, two

weeks later,

a nudge, a knee

as you elbow round inside—

acrobat, apple

of our eye

we can't

yet see....

And poetry helps us remember—keeping alive the cultural legacy of a people. Here are the last lines of Jake Adam York's poem "Postscript," written for slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers:

and because you are nowhere

you are everywhere,

in the face of which I'd ask

how can I say anything,

in the face of which I'd ask

how can I say nothing at all?

Occasions for the kind of quiet contemplation and focus that poetry seems to require are rare, and yet the need for poetry arises again and again. The act of making poetry is an act of hope.

—Natasha Trethewey, United States poet laureate from 2012 to 2014

Illustration: Peter Oumanski

It's Not a Test

To enjoy poetry, the only requirement is to relax.

Have you a gold cup

dedicated to thought

that is like clear water

held in a flower?

—From "The Question" by Robert Duncan

Even in elementary school it troubled me when our teacher, with all good intentions, read a poem to the class, then asked, "What does it mean?"

My problem wasn't with the question, but with the idea that there was an Answer. I'm not sure why I resisted this way of reading poetry. I didn't come from a literary family. If there's a social class into which you must be born or an educational level you have to reach in order to appreciate poetry, no one ever told me, though someone must have patted me on the head at some point as I puzzled over a poem, and said, "You don't have to understand it."

A poem is not a test. Readers of poetry can't fail. When you read a poem, you can, if you like, cling stubbornly to a "wrong" answer to the question, "What does it mean?"

Poems aren't meant to express what can be expressed in everyday language. Like dreams, they come to offer us strange new experiences, or to remind us of those we thought we'd forgotten. They can be understood in the parts of our brain that appreciate sounds, or smell, or the experience of awakening and feeling unaccountably anxious. The need for poetry, and its insistence on its own sacred mystery, arrived with the first poet who spoke the first poem, which may have been shouted in anger, sung over a grave, or whispered to a lover. But it wasn't intended to be explained. So, "Do you have a gold cup...?"

Yes. You do. It is your openness to being filled. It's your willingness to let go of the need to understand, and to enjoy instead the thrillof feeling. Go out in search of poems you like, that can become yours. What they mean to anyone else is irrelevant. They mean what a leaf blowing across the freeway means. They mean what the open eye of a goldfish looking into your eye means. The limitless pleasures of poetry are yours for the taking.

—Laura Kasischke, 2012 recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry.

dedicated to thought

that is like clear water

held in a flower?

—From "The Question" by Robert Duncan

Even in elementary school it troubled me when our teacher, with all good intentions, read a poem to the class, then asked, "What does it mean?"

My problem wasn't with the question, but with the idea that there was an Answer. I'm not sure why I resisted this way of reading poetry. I didn't come from a literary family. If there's a social class into which you must be born or an educational level you have to reach in order to appreciate poetry, no one ever told me, though someone must have patted me on the head at some point as I puzzled over a poem, and said, "You don't have to understand it."

A poem is not a test. Readers of poetry can't fail. When you read a poem, you can, if you like, cling stubbornly to a "wrong" answer to the question, "What does it mean?"

Poems aren't meant to express what can be expressed in everyday language. Like dreams, they come to offer us strange new experiences, or to remind us of those we thought we'd forgotten. They can be understood in the parts of our brain that appreciate sounds, or smell, or the experience of awakening and feeling unaccountably anxious. The need for poetry, and its insistence on its own sacred mystery, arrived with the first poet who spoke the first poem, which may have been shouted in anger, sung over a grave, or whispered to a lover. But it wasn't intended to be explained. So, "Do you have a gold cup...?"

Yes. You do. It is your openness to being filled. It's your willingness to let go of the need to understand, and to enjoy instead the thrillof feeling. Go out in search of poems you like, that can become yours. What they mean to anyone else is irrelevant. They mean what a leaf blowing across the freeway means. They mean what the open eye of a goldfish looking into your eye means. The limitless pleasures of poetry are yours for the taking.

—Laura Kasischke, 2012 recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry.

On Reflection

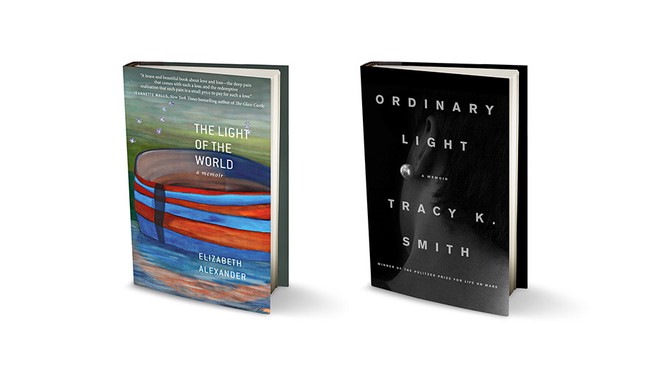

A pair of memoirs chronicle two poets' paths.

When good poets write memoirs, we get the benefit of experiencing actual events as filtered through a transcendent art form. Two sublime new examples are Elizabeth Alexander's The Light of the World (Grand Central) and Tracy K. Smith's Ordinary Light (Knopf).

"The story seems to begin with catastrophe but in fact began earlier and is not a tragedy but rather a love story." This is the opening sentence of Alexander's chronicle of her marriage and the sudden death of her husband, Ficre Ghebreyesus, at age 50. What unfolds is a glimpse into the very soul of true love. We don't often get to see that in this era of confessional accounts of dysfunctional relationships, and we wouldn't be seeing it now if not for the unspeakable heartbreak of Ficre's passing.

Theirs is a union made of art. Ficre was a chef and a painter, and Alexander weaves recipes that read like verse into her story. She shows us how feeding your family and remembering to be aware of the small details of everyday life are the bedrocks of true connection. In this book of prose, each page is a poem.

Ordinary Light is also a feast, one of startling insight into the complex doings of average people. Smith writes about her childhood with humor and acute insight; though raised in a military family with Christian values, she accepts nothing at face value. Her childhood self sees through human hypocrisy with laserlike precision, as when a visiting Bible thumper strikes her as "odd, a trifle cagey," someone whose life is such a wreck that he's thrown himself on God's mercy, where "relief could be seen to impart a feeling of redemption." A trip to Alabama, where her mother grew up, brings an awareness of what went before: the civil rights movement, segregation, slavery itself. Smith's attempts to reconcile this legacy with her own journey into the hallowed halls of the highly educated makes for a riveting read.

—Terre Roche

When good poets write memoirs, we get the benefit of experiencing actual events as filtered through a transcendent art form. Two sublime new examples are Elizabeth Alexander's The Light of the World (Grand Central) and Tracy K. Smith's Ordinary Light (Knopf).

"The story seems to begin with catastrophe but in fact began earlier and is not a tragedy but rather a love story." This is the opening sentence of Alexander's chronicle of her marriage and the sudden death of her husband, Ficre Ghebreyesus, at age 50. What unfolds is a glimpse into the very soul of true love. We don't often get to see that in this era of confessional accounts of dysfunctional relationships, and we wouldn't be seeing it now if not for the unspeakable heartbreak of Ficre's passing.

Theirs is a union made of art. Ficre was a chef and a painter, and Alexander weaves recipes that read like verse into her story. She shows us how feeding your family and remembering to be aware of the small details of everyday life are the bedrocks of true connection. In this book of prose, each page is a poem.

Ordinary Light is also a feast, one of startling insight into the complex doings of average people. Smith writes about her childhood with humor and acute insight; though raised in a military family with Christian values, she accepts nothing at face value. Her childhood self sees through human hypocrisy with laserlike precision, as when a visiting Bible thumper strikes her as "odd, a trifle cagey," someone whose life is such a wreck that he's thrown himself on God's mercy, where "relief could be seen to impart a feeling of redemption." A trip to Alabama, where her mother grew up, brings an awareness of what went before: the civil rights movement, segregation, slavery itself. Smith's attempts to reconcile this legacy with her own journey into the hallowed halls of the highly educated makes for a riveting read.

—Terre Roche

From the April 2015 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine