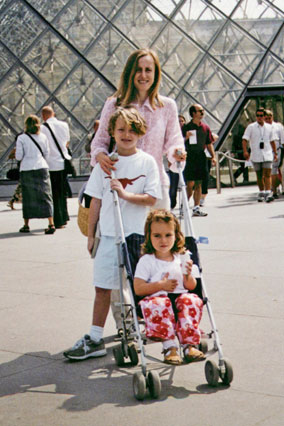

The Stroller Diaries

Photo: Courtesy of Mona Simpson

Mona Simpson, author of the modern mother-daughter classic Anywhere but Here, explores what happens when a nanny joins the family.

On an uncommonly windy Sunday afternoon, Mona Simpson meets me to talk about her first novel in ten years. That it's a weekend, a time she usually reserves for her two children, seems fitting, since the tension between work and motherhood is a major theme in the book. My Hollywood tells the parallel stories of Claire, a composer whose husband's work schedule regularly strands her with a newborn, and Lola, her middle-aged Filipina nanny. "It didn't start as a book about mothers," Simpson says, sitting at a small metal table outside a Brentwood coffeehouse. "Originally it was about children, or even more about the immigrant nannies who care for them." The inspiration came from a group of women she "fell in with" at the Santa Monica park where she took her baby son after moving to Southern California from New York in late 1993.Like Claire, Simpson came west for her husband's career (Simpson was married to Richard Appel, who was on a ten-week sitcom-writing contract). Also like Claire, she was often left alone with an infant and had to learn how to balance her professional and domestic life. But don't push her on the similarities; Simpson says she has used her life only as a jumping- off point for her work. "I don't really take the people as much as I take the situations," she says. Her novella, Off Keck Road, involved a woman coming of age and growing old in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where Simpson spent part of her childhood. A Regular Guy (1996) is loosely based on the story of her brother, Apple chairman Steve Jobs. (Because he was given up for adoption as an infant, the two never met until they were adults.)

With My Hollywood, Simpson has closed the circle that began with her debut, the 1986 best-seller Anywhere but Here. In that book, published when she was 29, she wrote elegantly and ruthlessly about the relationship between a mother and her adolescent daughter. "We fought," the girl tells us in the very first sentence. "When my mother and I crossed state lines in the stolen car, I'd sit against the window and wouldn't talk." By the bottom of the first page, that mother has left her daughter by the side of the road.

Twenty-four years later, Simpson writes from the perspective of a mother, overwhelmed and lacking in her own way. "I was becoming a woman who sighed," Claire observes early in the novel. "So now I had my baby and I saw why women got so little done. How much my own mother had given. Why so many people feel mad at their mothers; because whatever childhood was or wasn't, they're the ones who made it. Fathers loomed above it all, high trees."

This is where Lola comes in, as a caretaker not just to Claire's son, William, but also to Claire herself. The novel is deft in explaining the fluid role of the nanny, both in the family and outside it, essential and superfluous at once. "Do not worry," Lola tells William. "Your Lola will not leave you." Employers, however, are not nearly so steadfast. "You're part of the family until we fire you," Simpson says simply, her voice uninflected, her eyes flashing as she lays the matter bare. William outgrows Lola. And so does Claire, who has learned how to be a mother from the example that her nanny set. The family will go on as if she were never there.

This is classic Simpson; in her writing, as in her life, she is direct, unsentimental, an observer coolly marking down the customs of the domestic world. "It's all a question of balance," she says, referring to the small moments, the household dynamics, in which the most serious and potent truths are told. "There's a lot of ambiguity and contradiction in every family. And women get blamed when things go wrong."

Get the reading group guide

Browse O's complete 2010 summer reading list

Photo: Ben Goldstein/Studio D