By Norris Church Mailer

432 pages; Random House

Just how irresistible was Norman Mailer? Gloria Steinem said that anybody who would marry him couldn't be "healthy, well-adjusted, conscious, or aware"—but she was friends with him. Ditto the feminist Germaine Greer, close to him around the time Mailer was quoted as saying, "A little bit of rape is good for a man's soul." And then there was New York congresswoman Bella Abzug, who, when she first met Norris, his sixth wife, offered her home phone number in case Norris ever needed to get away from him. Yet Abzug had wholeheartedly supported Mailer in his quixotic bid for New York City mayor in 1969. Go figure.

These are just a few of the revelations in A Ticket to the Circus, Norris Church Mailer's funny, generous, shockingly forthright memoir about life with the lion of literature—a notorious philanderer until age and infirmity declawed him. Ticket is at once a glimpse into New York's social and literary whirl, a love story, and an attempt to explain the unexplainable: why any woman would choose to live with Mailer's innumerable cruelties—as large as his compulsive womanizing and as small as his habit of walking up to Norris at a party if she was having too good a time and whispering in her ear, "You're losing your looks."

Seeking to understand why such a gorgeous, funny woman would put up with this nonsense, I'm meeting with her in the living room of the wood-paneled Brooklyn Heights apartment she and Mailer shared for most of their marriage. Photographs and paintings of his nine children and assorted extended family are everywhere. There is a ravishing series of photos of the couple: A pregnant Norris, draped languidly over her husband, wears a diaphanous gown; Mailer, an expression of lordly possession. The sexual chemistry is palpable. "When you have that," Norris says with a sly smile, "you can forgive a lot."

The woman raised as Barbara Jean Davis in Russellville, Arkansas, was blessed with a russet beauty. Crowned Little Miss Little Rock at the age of 3, she later caught the eye of an up-and-coming Arkansas politician whom she saw throughout 1974. "Dating" doesn't exactly describe Norris's time with Bill Clinton, but the term booty call had not yet been invented. "He would drop by my house at 2 a.m.," she says. "We weren't really talking about public policy."

In 1975 Barbara Jean met Mailer when he was speaking at a local college. He was still married to one wife and living with someone else, but these entanglements did not impede the epic affair that followed. "We bounce into each other like sunlight," he wrote to her after their first night together. "The time in Little Rock keeps reflecting back into the room for me so that no matter the hour or the place there we are swimming in that red gold light and there you are smelling like cinnamon. God, you're attractive."

Like all mash letters not intended for publication, Mailer's are, well, a little cringeworthy. So why did Norris decide to publish them? "I gave a lot of thought to it," she says. "I guess...so much happened later, and he was such a cheat later on, I just wanted this aspect of our relationship to be known. That he was crazy about me. That it was real."

An unsettling discovery—and why she didn't leave

432 pages; Random House

Just how irresistible was Norman Mailer? Gloria Steinem said that anybody who would marry him couldn't be "healthy, well-adjusted, conscious, or aware"—but she was friends with him. Ditto the feminist Germaine Greer, close to him around the time Mailer was quoted as saying, "A little bit of rape is good for a man's soul." And then there was New York congresswoman Bella Abzug, who, when she first met Norris, his sixth wife, offered her home phone number in case Norris ever needed to get away from him. Yet Abzug had wholeheartedly supported Mailer in his quixotic bid for New York City mayor in 1969. Go figure.

These are just a few of the revelations in A Ticket to the Circus, Norris Church Mailer's funny, generous, shockingly forthright memoir about life with the lion of literature—a notorious philanderer until age and infirmity declawed him. Ticket is at once a glimpse into New York's social and literary whirl, a love story, and an attempt to explain the unexplainable: why any woman would choose to live with Mailer's innumerable cruelties—as large as his compulsive womanizing and as small as his habit of walking up to Norris at a party if she was having too good a time and whispering in her ear, "You're losing your looks."

Seeking to understand why such a gorgeous, funny woman would put up with this nonsense, I'm meeting with her in the living room of the wood-paneled Brooklyn Heights apartment she and Mailer shared for most of their marriage. Photographs and paintings of his nine children and assorted extended family are everywhere. There is a ravishing series of photos of the couple: A pregnant Norris, draped languidly over her husband, wears a diaphanous gown; Mailer, an expression of lordly possession. The sexual chemistry is palpable. "When you have that," Norris says with a sly smile, "you can forgive a lot."

The woman raised as Barbara Jean Davis in Russellville, Arkansas, was blessed with a russet beauty. Crowned Little Miss Little Rock at the age of 3, she later caught the eye of an up-and-coming Arkansas politician whom she saw throughout 1974. "Dating" doesn't exactly describe Norris's time with Bill Clinton, but the term booty call had not yet been invented. "He would drop by my house at 2 a.m.," she says. "We weren't really talking about public policy."

In 1975 Barbara Jean met Mailer when he was speaking at a local college. He was still married to one wife and living with someone else, but these entanglements did not impede the epic affair that followed. "We bounce into each other like sunlight," he wrote to her after their first night together. "The time in Little Rock keeps reflecting back into the room for me so that no matter the hour or the place there we are swimming in that red gold light and there you are smelling like cinnamon. God, you're attractive."

Like all mash letters not intended for publication, Mailer's are, well, a little cringeworthy. So why did Norris decide to publish them? "I gave a lot of thought to it," she says. "I guess...so much happened later, and he was such a cheat later on, I just wanted this aspect of our relationship to be known. That he was crazy about me. That it was real."

An unsettling discovery—and why she didn't leave

Curiously, given his history, Norris claims it never occurred to her—even after she'd moved to New York and borne his son—that there may have been other women. And perhaps for a number of years there weren't. Then came the fateful day when, after 11 years of marriage, she stepped foot in her husband's office. He had given her the key, so "he must have wanted me to find everything." Bursting out of his desk drawer were photos and letters from innumerable liaisons. In his typical fashion, Mailer confessed—and kept on confessing, in lurid detail, for months. Here, in his wife's rather hilarious recounting, Mailer becomes a small man—the comical, mealy-mouthed husband. With a straight face, Mailer told his wife that his cheating was part of his research for Harlot's Ghost: To understand CIA operatives, he had to live a double life, he said.

He was complex; that's for sure. "Part of him was this wonderful, sweet, intelligent, terrific, funny guy that I was madly in love with. And another part, I just couldn't stand," Norris says now. Still, she did not leave; instead she made the decision to "take a step away from [him] in my heart...it was better to be a little bit less in love." Mailer noticed the withdrawal and would have liked to win her back, she says, but he was incorrigible. On his deathbed in 2007, he awoke from a coma long enough to sip his favorite drink—rum and orange juice—and kiss a family friend on the mouth.

Remembering that day, Norris is surprised it wasn't she in the hospital; diagnosed with a rare form of gastrointestinal cancer ten years ago, she was not expected to last more than a year or two. But she's still here at age 61, fragile although stunning as ever. She remains determined to tell her truth. "I needed to exorcise some parts of my life," she says, "and maybe I wanted my own bit of immortality, too." —Judith Newman

He was complex; that's for sure. "Part of him was this wonderful, sweet, intelligent, terrific, funny guy that I was madly in love with. And another part, I just couldn't stand," Norris says now. Still, she did not leave; instead she made the decision to "take a step away from [him] in my heart...it was better to be a little bit less in love." Mailer noticed the withdrawal and would have liked to win her back, she says, but he was incorrigible. On his deathbed in 2007, he awoke from a coma long enough to sip his favorite drink—rum and orange juice—and kiss a family friend on the mouth.

Remembering that day, Norris is surprised it wasn't she in the hospital; diagnosed with a rare form of gastrointestinal cancer ten years ago, she was not expected to last more than a year or two. But she's still here at age 61, fragile although stunning as ever. She remains determined to tell her truth. "I needed to exorcise some parts of my life," she says, "and maybe I wanted my own bit of immortality, too." —Judith Newman

By Diana Joseph

224 pages; Amy Einhorn

Diana Joseph is one scrappy, wisecracking memoirist whose brazen sexuality, golden heart and hard-boiled sense of humor will have readers snorting and shaking their heads. In I'm Sorry You Feel That Way, Joseph pulls no punches in describing her roughneck upbringing, disastrous relationships and difficulties raising her son as a single mom. Then there's the incorrigible nameless dog: "The puppy would get depressed," she writes. "He'd sigh. He'd stare at the wall or at his feet in an impassive way. He'd burp like a human burps. Or he'd shred something...a book, a sweater, a 20-dollar bill under the dining room table...I understood him completely." Make like that puppy and devour this book along with some double-stuff Oreos after a bad day, and you might live to see the sun. — Kristy Davis

224 pages; Amy Einhorn

Diana Joseph is one scrappy, wisecracking memoirist whose brazen sexuality, golden heart and hard-boiled sense of humor will have readers snorting and shaking their heads. In I'm Sorry You Feel That Way, Joseph pulls no punches in describing her roughneck upbringing, disastrous relationships and difficulties raising her son as a single mom. Then there's the incorrigible nameless dog: "The puppy would get depressed," she writes. "He'd sigh. He'd stare at the wall or at his feet in an impassive way. He'd burp like a human burps. Or he'd shred something...a book, a sweater, a 20-dollar bill under the dining room table...I understood him completely." Make like that puppy and devour this book along with some double-stuff Oreos after a bad day, and you might live to see the sun. — Kristy Davis

Photo: Ben Goldstein/Studio D

By Roger Rosenblatt

176 pages; Ecco

Comparing heartbreaks is a zero-sum game. Between the loss of a child and the childhood loss of a parent, there is no determining which hurts more. But as veteran journalist and essayist Roger Rosenblatt reveals in Making Toast, a deeply affecting and unsparing memoir of moving in with his three grandchildren after his daughter's sudden death, sharing grief can double the chance of survival.

Soon after 38-year-old Amy Solomon dies of a heart attack in her home gym, Rosenblatt and his wife, Ginny, leave Long Island and take up residence in Amy's house in Bethesda, Maryland, with Jessica, 6; Sammy, 4; Bubbies, as 1-year-old James is called; and Harris, the son-in-law whom they always liked but never expected to have as a housemate. A situation fraught with possible disaster becomes an occasion for mutual healing. It turns out that getting his family through this enormous sadness is the only way Rosenblatt can get through it himself.

Making Toast pays tribute to the quotidian pleasures of living with children, to the agony of watching them suffer, and to the serious business of growing up. Rosenblatt tells his story anecdotally, and the moments he chooses go for the gut: a small boy lying on the floor playing dead, the way his mom seemed to be when he found her. A little girl at a family gathering raging against the unfairness of her cousins having mothers while she is motherless. A posthumous birthday party where a child, when asked what Mommy would have wished for, answers, "To be alive." A grandfather taking out his fury on a punching bag bought for his grandchildren. Sad but somehow triumphant, this memoir is a celebration of family, and of how, even in the deepest sorrow, we can discover new links of love and the will to go on. — Ellen Feldman

176 pages; Ecco

Comparing heartbreaks is a zero-sum game. Between the loss of a child and the childhood loss of a parent, there is no determining which hurts more. But as veteran journalist and essayist Roger Rosenblatt reveals in Making Toast, a deeply affecting and unsparing memoir of moving in with his three grandchildren after his daughter's sudden death, sharing grief can double the chance of survival.

Soon after 38-year-old Amy Solomon dies of a heart attack in her home gym, Rosenblatt and his wife, Ginny, leave Long Island and take up residence in Amy's house in Bethesda, Maryland, with Jessica, 6; Sammy, 4; Bubbies, as 1-year-old James is called; and Harris, the son-in-law whom they always liked but never expected to have as a housemate. A situation fraught with possible disaster becomes an occasion for mutual healing. It turns out that getting his family through this enormous sadness is the only way Rosenblatt can get through it himself.

Making Toast pays tribute to the quotidian pleasures of living with children, to the agony of watching them suffer, and to the serious business of growing up. Rosenblatt tells his story anecdotally, and the moments he chooses go for the gut: a small boy lying on the floor playing dead, the way his mom seemed to be when he found her. A little girl at a family gathering raging against the unfairness of her cousins having mothers while she is motherless. A posthumous birthday party where a child, when asked what Mommy would have wished for, answers, "To be alive." A grandfather taking out his fury on a punching bag bought for his grandchildren. Sad but somehow triumphant, this memoir is a celebration of family, and of how, even in the deepest sorrow, we can discover new links of love and the will to go on. — Ellen Feldman

Photo: Marko Metzinger/Studio D

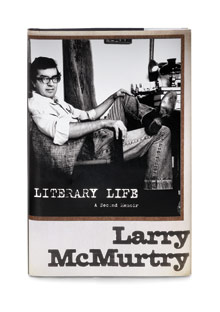

By Larry McMurtry

192 pages; Simon & Schuster

"For much of my adult life I've been tempted, sporadically, to visit fortune-tellers, just to get their opinion on my prospects, as it were," says Larry McMurtry in Literary Life, his second memoir in the trilogy that began with Books and will culminate in Hollywood, a juicy (we hope) exposé of his screenwriting years. Whether ogling racecars with Susan Sontag or waxing skeptical about winning the Pulitzer Prize, McMurtry, now 73, is the master of the showstopping anecdote: Stumped midway through a novel, he saw an old church bus parked alongside the road near Ponder, Texas. On its side: LONESOME DOVE BAPTIST CHURCH. Writer's block, hasta luego. —Kristy Davis

192 pages; Simon & Schuster

"For much of my adult life I've been tempted, sporadically, to visit fortune-tellers, just to get their opinion on my prospects, as it were," says Larry McMurtry in Literary Life, his second memoir in the trilogy that began with Books and will culminate in Hollywood, a juicy (we hope) exposé of his screenwriting years. Whether ogling racecars with Susan Sontag or waxing skeptical about winning the Pulitzer Prize, McMurtry, now 73, is the master of the showstopping anecdote: Stumped midway through a novel, he saw an old church bus parked alongside the road near Ponder, Texas. On its side: LONESOME DOVE BAPTIST CHURCH. Writer's block, hasta luego. —Kristy Davis

By Malcolm Jones

240 ages; Pantheon

Some people fear losing their parents; others couldn't lose them if they tried. "Nothing about her dying surprised me much," writes Malcolm Jones about the death of his mother. "It's how fiercely she stayed alive after she was dead that caught me unaware." Jones's warmly elegant memoir, Little Boy Blues, recalls his childhood in an impoverished, fractured North Carolina household of the 1950s and '60s. Smitten as a young boy with movies and magic tricks, and "furtively vain about my hard life," Jones retrieves elusive memories—of his emotionally stranded mother; his alcoholic, mostly absent father; his devout, "casually racist" aunt and uncle—and creates a rich tapestry of Southern life. —Cathleen Medwick

240 ages; Pantheon

Some people fear losing their parents; others couldn't lose them if they tried. "Nothing about her dying surprised me much," writes Malcolm Jones about the death of his mother. "It's how fiercely she stayed alive after she was dead that caught me unaware." Jones's warmly elegant memoir, Little Boy Blues, recalls his childhood in an impoverished, fractured North Carolina household of the 1950s and '60s. Smitten as a young boy with movies and magic tricks, and "furtively vain about my hard life," Jones retrieves elusive memories—of his emotionally stranded mother; his alcoholic, mostly absent father; his devout, "casually racist" aunt and uncle—and creates a rich tapestry of Southern life. —Cathleen Medwick

By Frank Bruni

368 pages; Penguin

When he was a toddler, he screamed for seconds, thirds. Later, he lunged at precooked chicken pieces while driving ("If I needed to liberate both hands, I used my left knee to steer"). Born Round is New York Times writer Frank Bruni's hugely enjoyable memoir about the shame and saucy joys of overeating, about endless dieting ("Yo-Yo Me"), desperate dating, "sleep-eating" in the dead of night, and learning to think judiciously about the dizzying danger zone of dinner.—Cathleen Medwick

368 pages; Penguin

When he was a toddler, he screamed for seconds, thirds. Later, he lunged at precooked chicken pieces while driving ("If I needed to liberate both hands, I used my left knee to steer"). Born Round is New York Times writer Frank Bruni's hugely enjoyable memoir about the shame and saucy joys of overeating, about endless dieting ("Yo-Yo Me"), desperate dating, "sleep-eating" in the dead of night, and learning to think judiciously about the dizzying danger zone of dinner.—Cathleen Medwick

By Tim Page

208 pages; Doubleday

As a child and teenager, Tim Page had to master making eye contact. He didn't like being touched. His artwork was borderline-bizarre, his writing single-mindedly detailed, his early fascinations (silent movies and music) headlong, his social instincts basically nonexistent. Teachers sometimes dubbed him a genius—then flunked him. "Perhaps I am not quite a mammal," Page recalls speculating at one point in his fascinating new memoir, Parallel Play.

After a lifetime of silently wondering and fretting about his own "driven, uncomfortable" personality, nine years ago the now-54-year-old Pulitzer Prize–winning former music critic for The Washington Post was diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome—a developmental disorder with links to autism, whose symptoms include obsessiveness, an inability to connect with same-age peers, and a tendency to misread social cues. In this tender but unsparing look back, Page holds up the pages of his own life for reappraisal—Wait, so this is what I had all along?—leaving readers to ponder how a condition that bedevils and isolates can also yield magicianly talent, originality, and grit.—Peter Smith

208 pages; Doubleday

As a child and teenager, Tim Page had to master making eye contact. He didn't like being touched. His artwork was borderline-bizarre, his writing single-mindedly detailed, his early fascinations (silent movies and music) headlong, his social instincts basically nonexistent. Teachers sometimes dubbed him a genius—then flunked him. "Perhaps I am not quite a mammal," Page recalls speculating at one point in his fascinating new memoir, Parallel Play.

After a lifetime of silently wondering and fretting about his own "driven, uncomfortable" personality, nine years ago the now-54-year-old Pulitzer Prize–winning former music critic for The Washington Post was diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome—a developmental disorder with links to autism, whose symptoms include obsessiveness, an inability to connect with same-age peers, and a tendency to misread social cues. In this tender but unsparing look back, Page holds up the pages of his own life for reappraisal—Wait, so this is what I had all along?—leaving readers to ponder how a condition that bedevils and isolates can also yield magicianly talent, originality, and grit.—Peter Smith

By Staceyann Chin

288 pages; Scribner

A feisty, fresh-mouthed waif, poet and performer Staceyann Chin was born on the floor of a shack in rural Jamaica and batted from one brutal, Bible-thumping "auntie" to another after her mother flew the coop and her likely father, a Chinese-Jamaican businessman, denied his paternity. Chin's hurricane-strength memoir of social and sexual dislocation, The Other Side of Paradise, might make her seem pathetic if she weren't so hell-bent on thriving. "It tickles me to think that from my very first breath, everyone expected me to stop breathing," she writes, laughing, as always, in the dark.—Cathleen Medwick

288 pages; Scribner

A feisty, fresh-mouthed waif, poet and performer Staceyann Chin was born on the floor of a shack in rural Jamaica and batted from one brutal, Bible-thumping "auntie" to another after her mother flew the coop and her likely father, a Chinese-Jamaican businessman, denied his paternity. Chin's hurricane-strength memoir of social and sexual dislocation, The Other Side of Paradise, might make her seem pathetic if she weren't so hell-bent on thriving. "It tickles me to think that from my very first breath, everyone expected me to stop breathing," she writes, laughing, as always, in the dark.—Cathleen Medwick

By Water Kirn

288 pages; Doubleday

Walter Kirn is an idealist. His keen and up-to-the-minute novels and short stories over the years have often pitted the gloriously, even delusionally well-intentioned against corrupt institutions and powers that masquerade as all that is proper and approved. Now, as he tells his own story in a tough, funny, and moving memoir, Lost in the Meritocracy, we learn that Kirn's original beleaguered innocent was himself. He examines with a kind of pained amusement his dogged Midwestern faith—in his schools, his parents, his church, and in the whole construct of morality and achievement as it was peddled to the late-20th-century American kid of a certain class and intellect. What's such great fun about the book is the intense good humor with which he looks back, and the wonderful portraits he provides of the side characters in his life: a vividly traditional older man who acted as an early mentor, a deranged sex-maniac schoolteacher, the lofty and the strange among his childhood peers—and then his soul-salting years at Princeton, where he expected enlightenment and discovered fecklessness, thievery, and self-promotion instead. There's a kind of joyous cackle behind these colorful scenes, and a sadness, too, both finally giving way to a clean-edged wisdom that infiltrates his story as he leads us toward his moral awakening. — Vince Passaro

288 pages; Doubleday

Walter Kirn is an idealist. His keen and up-to-the-minute novels and short stories over the years have often pitted the gloriously, even delusionally well-intentioned against corrupt institutions and powers that masquerade as all that is proper and approved. Now, as he tells his own story in a tough, funny, and moving memoir, Lost in the Meritocracy, we learn that Kirn's original beleaguered innocent was himself. He examines with a kind of pained amusement his dogged Midwestern faith—in his schools, his parents, his church, and in the whole construct of morality and achievement as it was peddled to the late-20th-century American kid of a certain class and intellect. What's such great fun about the book is the intense good humor with which he looks back, and the wonderful portraits he provides of the side characters in his life: a vividly traditional older man who acted as an early mentor, a deranged sex-maniac schoolteacher, the lofty and the strange among his childhood peers—and then his soul-salting years at Princeton, where he expected enlightenment and discovered fecklessness, thievery, and self-promotion instead. There's a kind of joyous cackle behind these colorful scenes, and a sadness, too, both finally giving way to a clean-edged wisdom that infiltrates his story as he leads us toward his moral awakening. — Vince Passaro

By Christopher Buckley

251 pages; Twelve

Christopher Buckley's lovely Losing Mum and Pup is the story of two deaths—that of his glamorous and funny mother, socialite Pat Buckley, and brilliant and funny father, conservative writer William F. Buckley—within a year of each other in 2007 and 2008.

Buckley, a veteran satirist, wrings a lot of laughs out of upsetting material, namely the experience of wrangling sick and willful parents, along with kindly doctors, an unctuous funeral director, bloodthirsty reporters, and some very famous friends. Like most memoirs written soon after the events they describe, this one is not terribly introspective. Instead the pleasure lies in getting to know one of New York's great power couples better. We learn of Bill's penchant for peeing out of moving cars, Pat's for telling whopping lies at dinner parties, and we get to read a bit of Bill's writing, which is so lucid and graceful it's obvious why he became the voice of conservative politics in America. While Buckley's memories of his parents are often unsparing—he is frequently appalled at their recklessness—they add up to the sweetest possible tribute. These were charming people, Buckley makes clear, and charming because they always knew exactly who they were.

251 pages; Twelve

Christopher Buckley's lovely Losing Mum and Pup is the story of two deaths—that of his glamorous and funny mother, socialite Pat Buckley, and brilliant and funny father, conservative writer William F. Buckley—within a year of each other in 2007 and 2008.

Buckley, a veteran satirist, wrings a lot of laughs out of upsetting material, namely the experience of wrangling sick and willful parents, along with kindly doctors, an unctuous funeral director, bloodthirsty reporters, and some very famous friends. Like most memoirs written soon after the events they describe, this one is not terribly introspective. Instead the pleasure lies in getting to know one of New York's great power couples better. We learn of Bill's penchant for peeing out of moving cars, Pat's for telling whopping lies at dinner parties, and we get to read a bit of Bill's writing, which is so lucid and graceful it's obvious why he became the voice of conservative politics in America. While Buckley's memories of his parents are often unsparing—he is frequently appalled at their recklessness—they add up to the sweetest possible tribute. These were charming people, Buckley makes clear, and charming because they always knew exactly who they were.

By Azar Nafisi

368 pages; Random House

Living in Iran under the repressive Khomeini regime, Azar Nafisi jotted down a list of things she was obliged—for personal and political reasons—to keep secret. One item she recorded, "reading Lolita in Tehran," would become the title of her 2003 international best-seller. Her absorbing new book, Things I've Been Silent About, revisits that list to consider how deeply her family history was affected by the history of her native land. With dispassionate intelligence, Nafisi explores her troubled relationship with her difficult, remarkable mother, who became a member of the Iranian parliament, and with her loving father, whose career as mayor of Tehran was cut short by the false accusations that earned him a prison term during the Shah's regime. She writes about her father's infidelities, her parents' unhappy marriage and their eventual divorce, about the colorful cast of relatives and friends who frequented their home, the growth of her passion for books, her education in England and the United States, and about the upheavals that accompanied her country's transformation from a despotic monarchy to a state in which every detail of daily life was dictated by the clerics. Like Reading Lolita in Tehran, Things I've Been Silent About is a testament to the ways in which narrative truth-telling—from the greatest works of literature to the most intimate family stories—sustains and strengthens us as we struggle to weather the periodic violent storms that so drastically alter the landscape—and the world—in which we live. — Francine Prose

368 pages; Random House

Living in Iran under the repressive Khomeini regime, Azar Nafisi jotted down a list of things she was obliged—for personal and political reasons—to keep secret. One item she recorded, "reading Lolita in Tehran," would become the title of her 2003 international best-seller. Her absorbing new book, Things I've Been Silent About, revisits that list to consider how deeply her family history was affected by the history of her native land. With dispassionate intelligence, Nafisi explores her troubled relationship with her difficult, remarkable mother, who became a member of the Iranian parliament, and with her loving father, whose career as mayor of Tehran was cut short by the false accusations that earned him a prison term during the Shah's regime. She writes about her father's infidelities, her parents' unhappy marriage and their eventual divorce, about the colorful cast of relatives and friends who frequented their home, the growth of her passion for books, her education in England and the United States, and about the upheavals that accompanied her country's transformation from a despotic monarchy to a state in which every detail of daily life was dictated by the clerics. Like Reading Lolita in Tehran, Things I've Been Silent About is a testament to the ways in which narrative truth-telling—from the greatest works of literature to the most intimate family stories—sustains and strengthens us as we struggle to weather the periodic violent storms that so drastically alter the landscape—and the world—in which we live. — Francine Prose

By Isabel Gillies

272 pages; Scribner

Josiah Robinson (not his real name) falls in love with Isabel Gillies (her real name) when he is 7. Fifteen years later, they remeet. This time Isabel reciprocates. Josiah, a beautiful poet ("Heathcliff with an earring"), says: "I will call you at 2:30 and if you aren't there I'll try every minute after until you are." Reader, she marries him. She abandons her New York acting career and follows him to a teaching post in Ohio.

"I missed any signs of trouble," Isabel writes in Happens Every Day: An All-Too-True Story. The reader won't. Isabel throws Josiah into her new best friend Sylvia's path over and over. She makes the thing happen she is most afraid of happening.

If Gillies weren't so plucky, she would break your heart. When the blow comes, it's her sons she is most devastated for. They are blessed to have her kind of love. It's the same kind of love Isabel got growing up, mother-lode mother love.

"I am not a writer, but I have been told I write good e-mails," Gillies says. I bet. — Patricia Volk

272 pages; Scribner

Josiah Robinson (not his real name) falls in love with Isabel Gillies (her real name) when he is 7. Fifteen years later, they remeet. This time Isabel reciprocates. Josiah, a beautiful poet ("Heathcliff with an earring"), says: "I will call you at 2:30 and if you aren't there I'll try every minute after until you are." Reader, she marries him. She abandons her New York acting career and follows him to a teaching post in Ohio.

"I missed any signs of trouble," Isabel writes in Happens Every Day: An All-Too-True Story. The reader won't. Isabel throws Josiah into her new best friend Sylvia's path over and over. She makes the thing happen she is most afraid of happening.

If Gillies weren't so plucky, she would break your heart. When the blow comes, it's her sons she is most devastated for. They are blessed to have her kind of love. It's the same kind of love Isabel got growing up, mother-lode mother love.

"I am not a writer, but I have been told I write good e-mails," Gillies says. I bet. — Patricia Volk

By Said Sayrafiezadeh

304 pages; Dial

When a 4-year-old boy defies his political activist mother and gobbles down boycotted grapes, it's a comic rebellion—one of many in Saïd Sayrafiezadeh's wry, lovely memoir, When Skateboards Will Be Free. From Brooklyn to Pittsburgh, Saïd snoozes through Socialist Workers Party meetings when all he really wants to do is hang out with the bigoted neighborhood kids who shun him. His American Jewish mother, a die-hard socialist, makes sure the two of them live in idealistic squalor, while his Iranian-born father, who has abandoned them, pursues his revolutionary dreams. "It was up to each of us to bear our private miseries alone," the author says, "until that glorious day in the future when...a perfect world would emerge." He's not holding his breath. — Cathleen Medwick

304 pages; Dial

When a 4-year-old boy defies his political activist mother and gobbles down boycotted grapes, it's a comic rebellion—one of many in Saïd Sayrafiezadeh's wry, lovely memoir, When Skateboards Will Be Free. From Brooklyn to Pittsburgh, Saïd snoozes through Socialist Workers Party meetings when all he really wants to do is hang out with the bigoted neighborhood kids who shun him. His American Jewish mother, a die-hard socialist, makes sure the two of them live in idealistic squalor, while his Iranian-born father, who has abandoned them, pursues his revolutionary dreams. "It was up to each of us to bear our private miseries alone," the author says, "until that glorious day in the future when...a perfect world would emerge." He's not holding his breath. — Cathleen Medwick

By Carrie Fisher

176 pages; Simon & Schuster

Don't cry for her. Carrie Fisher is too sassy to put up with sympathy—even if she did have a hellish Hollywood childhood, electroshock treatments for depression, bipolar episodes, and enough drugs and drink to explode a galaxy. "If my life wasn't funny it would just be true, and that is unacceptable," writes the iconic, ironic Star Wars heroine in Wishful Drinking, a memoir adapted from her one-woman show—and a star turn all its own. — Cathleen Medwick

176 pages; Simon & Schuster

Don't cry for her. Carrie Fisher is too sassy to put up with sympathy—even if she did have a hellish Hollywood childhood, electroshock treatments for depression, bipolar episodes, and enough drugs and drink to explode a galaxy. "If my life wasn't funny it would just be true, and that is unacceptable," writes the iconic, ironic Star Wars heroine in Wishful Drinking, a memoir adapted from her one-woman show—and a star turn all its own. — Cathleen Medwick

By Kelly McMasters

234 pages, PublicAffairs

The town of Shirley, on the East End of Long Island, has never been chic, and certainly never part of the fevered Hamptons summer scene, but to a 4-year-old and her hard-up young parents it did seem like a kind of paradise when they moved there in 1981. In Welcome to Shirley: A Memoir from an Atomic Town, Kelly McMasters charts how she came to understand that despite all she loved about Shirley (especially the loyalty of the neighborhood and the sense of open space and security she felt growing up there), it was somewhere to be ashamed of. More urgently, she learned that—all joking about Shirley's locals "glowing in the dark" aside—the acreage they lived on was the dumping site for three leaking nuclear reactors and countless chemical spills. Block by block, friend by friend, the number of cancer cases grows, including 16 local children diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer that typically hits one in four million children a year. In one of the book's most riveting moments, Randy Snell, the father of a stricken child, finds an official report that concludes that the only known cause of his daughter's disease is "low-level radiation exposure." McMasters tells the story of families such as the Snells and her own—her mother had benign tumors removed from her thyroid and breast—with passion and clarity. She also pulls off a small miracle in the telling, making rundown, unbeautiful Shirley a place of dignity, a place of heroic people and stubborn fighters, a place you'd be proud to call home. — Elaina Richardson

234 pages, PublicAffairs

The town of Shirley, on the East End of Long Island, has never been chic, and certainly never part of the fevered Hamptons summer scene, but to a 4-year-old and her hard-up young parents it did seem like a kind of paradise when they moved there in 1981. In Welcome to Shirley: A Memoir from an Atomic Town, Kelly McMasters charts how she came to understand that despite all she loved about Shirley (especially the loyalty of the neighborhood and the sense of open space and security she felt growing up there), it was somewhere to be ashamed of. More urgently, she learned that—all joking about Shirley's locals "glowing in the dark" aside—the acreage they lived on was the dumping site for three leaking nuclear reactors and countless chemical spills. Block by block, friend by friend, the number of cancer cases grows, including 16 local children diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer that typically hits one in four million children a year. In one of the book's most riveting moments, Randy Snell, the father of a stricken child, finds an official report that concludes that the only known cause of his daughter's disease is "low-level radiation exposure." McMasters tells the story of families such as the Snells and her own—her mother had benign tumors removed from her thyroid and breast—with passion and clarity. She also pulls off a small miracle in the telling, making rundown, unbeautiful Shirley a place of dignity, a place of heroic people and stubborn fighters, a place you'd be proud to call home. — Elaina Richardson

By Catherine Goldhammer

192 pages; Hudson Street

"I quickly learned that the primary joy and challenge of parenthood was to trust the spirit I had given birth to, and to know when to rein in and when to let go." So writes Catherine Goldhammer in Winging It (Hudson Street), a bemusing narrative about the struggles and pleasures of becoming a divorced-parent empty-nester. What will she do? Who will she be without the templates of marriage and motherhood? Fortunately, Goldhammer is strikingly imaginative (she wryly enjoys the excitement—and denouement—of a fantasy romance as much if not more than a real one), deeply engaged with her friends, family, and her small menagerie of pets, and, finally, optimistic about what she gracefully presents as the opportunities of aging. "We have our disappointments and our elations," she writes. "The twin cyclones of marriage and parenthood hit and consume our souls. ... Take away the newness of what we were, what our children now are, and maybe we have another chance to set forward into the promise of our future. Maybe everything unnecessary, everything false or fearful, is whittled away by time, and we do return to our essence, to whatever we have always been: what kind of tree, what kind of water, what kind of wind." — Valerie Monroe

192 pages; Hudson Street

"I quickly learned that the primary joy and challenge of parenthood was to trust the spirit I had given birth to, and to know when to rein in and when to let go." So writes Catherine Goldhammer in Winging It (Hudson Street), a bemusing narrative about the struggles and pleasures of becoming a divorced-parent empty-nester. What will she do? Who will she be without the templates of marriage and motherhood? Fortunately, Goldhammer is strikingly imaginative (she wryly enjoys the excitement—and denouement—of a fantasy romance as much if not more than a real one), deeply engaged with her friends, family, and her small menagerie of pets, and, finally, optimistic about what she gracefully presents as the opportunities of aging. "We have our disappointments and our elations," she writes. "The twin cyclones of marriage and parenthood hit and consume our souls. ... Take away the newness of what we were, what our children now are, and maybe we have another chance to set forward into the promise of our future. Maybe everything unnecessary, everything false or fearful, is whittled away by time, and we do return to our essence, to whatever we have always been: what kind of tree, what kind of water, what kind of wind." — Valerie Monroe

By Meredith Norton

224 pages Viking

With more gross-outs than a Judd Apatow comedy, Lopsided: How Having Breast Cancer Can Be Really Distracting is nonetheless a truly elegant memoir, thanks to the rigor of author Meredith Norton, who has never seen the situation that she doesn't find absurd. Being diagnosed with a deadly form of breast cancer in her early 30s, while living in Paris with her French husband and year-old son, is no exception. A cynic and self-deprecating clown, Norton is terrific at narrating the physical slapstick of battling this disease. But she's even better on the arrogance and pretense the cancer reveals, whether that of the four French doctors too full of themselves to look at her tumor-filled breast or her own dilettantish self.

"There we were," she concludes at the end of the 20-month ordeal she and her husband endured, "with the same annoying habits and bad manners, ungrateful, pessimistic, undisciplined, and bored. We were just as mediocre as when this whole drama began.

Ungrateful, pessimistic, undisciplined, bored. What can you say about a writer like this, except that she's fresh and adorable, and you hope she sticks around to produce at least another dozen surly, lovely books? — Michele Owens

224 pages Viking

With more gross-outs than a Judd Apatow comedy, Lopsided: How Having Breast Cancer Can Be Really Distracting is nonetheless a truly elegant memoir, thanks to the rigor of author Meredith Norton, who has never seen the situation that she doesn't find absurd. Being diagnosed with a deadly form of breast cancer in her early 30s, while living in Paris with her French husband and year-old son, is no exception. A cynic and self-deprecating clown, Norton is terrific at narrating the physical slapstick of battling this disease. But she's even better on the arrogance and pretense the cancer reveals, whether that of the four French doctors too full of themselves to look at her tumor-filled breast or her own dilettantish self.

"There we were," she concludes at the end of the 20-month ordeal she and her husband endured, "with the same annoying habits and bad manners, ungrateful, pessimistic, undisciplined, and bored. We were just as mediocre as when this whole drama began.

Ungrateful, pessimistic, undisciplined, bored. What can you say about a writer like this, except that she's fresh and adorable, and you hope she sticks around to produce at least another dozen surly, lovely books? — Michele Owens

By Meredith Hall

248 pages; Beacon

Nostalgic for the good old days of Norman Rockwell America? Without a Map may forever change the way you look at small-town life. Meredith Hall's memoir is a sobering portrayal of how punitive her close-knit New Hampshire community was in 1965 when, at the age of 16, she became pregnant in the course of a casual summer romance. Hall was expelled from high school, shunned by her friends and neighbors, cut loose by her parents, and forced to put up her baby for adoption. Unsurprisingly, the psychological damage she sustained was serious and persistent. After a reckless backpacking tour of Europe and the Middle East, Hall returned to her native state, married, had two sons, divorced, and was finally found by Paul, the son she'd been compelled to give away. Raised in New Hampshire, Paul had suffered through a childhood even more problematic than his (biological) mother's adolescence. As she documents her attempts to make sense of her parents' behavior and the cruelty of her son's adoptive father, Hall offers a testament to the importance of understanding and even forgiving the people who, however unconscious or unkind, have made us who we are. — Francine Prose

248 pages; Beacon

Nostalgic for the good old days of Norman Rockwell America? Without a Map may forever change the way you look at small-town life. Meredith Hall's memoir is a sobering portrayal of how punitive her close-knit New Hampshire community was in 1965 when, at the age of 16, she became pregnant in the course of a casual summer romance. Hall was expelled from high school, shunned by her friends and neighbors, cut loose by her parents, and forced to put up her baby for adoption. Unsurprisingly, the psychological damage she sustained was serious and persistent. After a reckless backpacking tour of Europe and the Middle East, Hall returned to her native state, married, had two sons, divorced, and was finally found by Paul, the son she'd been compelled to give away. Raised in New Hampshire, Paul had suffered through a childhood even more problematic than his (biological) mother's adolescence. As she documents her attempts to make sense of her parents' behavior and the cruelty of her son's adoptive father, Hall offers a testament to the importance of understanding and even forgiving the people who, however unconscious or unkind, have made us who we are. — Francine Prose

Steve Martin

224 pages; Scribner

Can a man who made comic history with a gag-arrow-through-the-head be frankly disarming? Yes, as comedian and writer Steve Martin demonstrates with warmth and precision in his memoir, Born Standing Up (Scribner). Read it for the intelligent musing, for the insights into burlesque, bombing (onstage, that is), and the wily art of getting laughs. — Cathleen Medwick

224 pages; Scribner

Can a man who made comic history with a gag-arrow-through-the-head be frankly disarming? Yes, as comedian and writer Steve Martin demonstrates with warmth and precision in his memoir, Born Standing Up (Scribner). Read it for the intelligent musing, for the insights into burlesque, bombing (onstage, that is), and the wily art of getting laughs. — Cathleen Medwick

By David Sheff

336 pages; Houghton Mifflin

Nic Sheff, charming, talented, college bound, was 18 when he discovered crystal meth. As he graphically describes it, "when I took those off-white crushed shards up that blue, cut plastic straw.... There was a feeling like—my God, this is what I've been missing my entire life. It completed me." At first his father had no idea. Then came the warning call from the school, the late nights, the lying, the ghoulish pallor and the wasting away. David's life became an eternity of waiting: for the phone to ring, the door to open; for a sign that his beautiful boy was safe. His fears were less gruesome than his son's reality: begging, dealing, promiscuous sex—whatever it took to dull the ache, the "feeling of torn-apartness" that had terrorized him at least since his parents' divorce when he was a child.

How does a father keep from drowning in guilt? How does a brilliant, tormented young man refuse a syringe full of bliss? Desperately seeking clues to Nic's disintegration, David Sheff became "addicted to [his] addiction," obsessing about Nic at the expense of his second wife and their two young children, while Nic kept emerging from rehab only to boomerang into an emotional black hole. The struggle is ongoing for both. As this narrative shows, fear still sabotages trust. Yet, David writes, "The constellation of these impulses that we call love feels like a miracle." — Cathleen Medwick

Looking for another great book? Find hundreds of ideas from O's Reading Room!

336 pages; Houghton Mifflin

Nic Sheff, charming, talented, college bound, was 18 when he discovered crystal meth. As he graphically describes it, "when I took those off-white crushed shards up that blue, cut plastic straw.... There was a feeling like—my God, this is what I've been missing my entire life. It completed me." At first his father had no idea. Then came the warning call from the school, the late nights, the lying, the ghoulish pallor and the wasting away. David's life became an eternity of waiting: for the phone to ring, the door to open; for a sign that his beautiful boy was safe. His fears were less gruesome than his son's reality: begging, dealing, promiscuous sex—whatever it took to dull the ache, the "feeling of torn-apartness" that had terrorized him at least since his parents' divorce when he was a child.

How does a father keep from drowning in guilt? How does a brilliant, tormented young man refuse a syringe full of bliss? Desperately seeking clues to Nic's disintegration, David Sheff became "addicted to [his] addiction," obsessing about Nic at the expense of his second wife and their two young children, while Nic kept emerging from rehab only to boomerang into an emotional black hole. The struggle is ongoing for both. As this narrative shows, fear still sabotages trust. Yet, David writes, "The constellation of these impulses that we call love feels like a miracle." — Cathleen Medwick

Looking for another great book? Find hundreds of ideas from O's Reading Room!