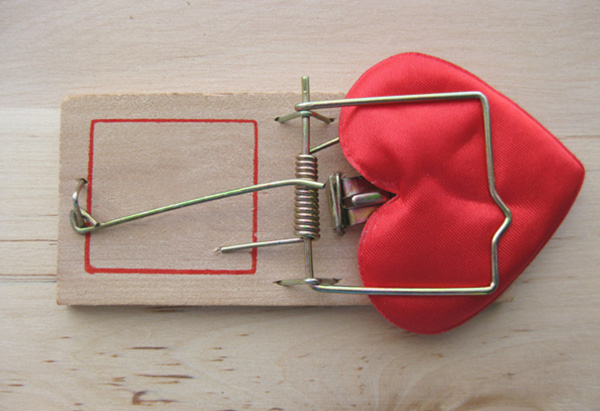

How did you find him, the guy who pushes all your wrong buttons? O reports on an amazingly effective new therapy that just might transform what we think about when we think about love.

Photo: Thinkstock

Not long ago, Jeffrey E. Young, PhD, a cognitive psychologist and clinical researcher at Columbia University Medical Center, met with a couple in crisis. The woman, let's call her Chloe, was brutally critical of her boyfriend, let's call him Dan. She thought Dan's teeth were ugly and wanted him to get them whitened; she thought his back was too hairy and complained that he wouldn't get regular waxing. It sent her into a rage when he was a few minutes late to pick her up on dates, even though Dan lived an hour away and traffic made exact arrival times nearly impossible. As Chloe continued with her onslaught, Young realized that Dan agreed with Chloe: Dan believed himself to be horribly flawed and thought Chloe was right to be angry with him. Although she was terribly critical of Dan, Young noted, Chloe loved him and was terrified of losing him.

If Young had been a Freudian therapist, he might have encouraged Dan and Chloe to speculate on the painful effect of childhood problems without suggesting specific ways to change their behavior. But Young began his career in the early '80s as a new therapy was gaining popularity—cognitive therapy, which teaches that how people think about events in their lives determines how they feel about them. Young, who studied with the man behind the therapy, Aaron T. Beck, was excited to be a part of a dynamic new method. But early on, he found that this approach alone was not enough to help clients with lifelong relationship troubles. "It was fine with people who'd been healthy and had problems only recently, but the majority of patients had problems that stemmed from their early life, and those people didn't respond well," he says.

Young began to spot a number of distinct, recurring patterns in his patients' psychological profiles—patterns laid down in early childhood that continued to shape their adult thoughts, actions, relationships, careers, and life choices. He called these habits "schemas," borrowing the ancient Greek word for "form," and he nicknamed them "lifetraps" to make it easier for his clients to understand both the concept and the risk of letting their schemas define them.

Although schema therapy began as an individual therapeutic strategy, it quickly turned into a couples therapy technique. "More than half the people we saw were coming in with problems with their relationship," Young says. "We thought, 'What if we got the partner in?' Once we did, we began to notice there was an interplay between them that was creating problems. One partner's schema would trigger the other's schema, and tensions would escalate." Some of the schemas dovetail—in a catastrophic way—each exacerbating the other. In fact, Young says, head-over-heels romantic attraction is often a sign of bad schema chemistry.

Young suspected that Dan suffered from the Defectiveness schema, which means that, when he was a child, his peers or family put him down, criticized him, and made him feel inferior. By asking questions in further sessions, he learned that Dan's mother favored his older brother and his father told him he was incompetent.

Chloe, on the other hand, was plagued by Unrelenting Standards. As a child, her family made her feel that, unless she was completely above reproach, she was a total failure. These are two of the 18 schemas Young has identified; a person may be affected or defined by any number of schemas—just as in astrology, people speak of an Aries who has a Cancer moon and Virgo rising. For instance, a patient may have the core schema of Emotional Deprivation and also be affected by the Abandonment and Self-Sacrifice schemas. (Take a quiz on common schemas.)

If Young had been a Freudian therapist, he might have encouraged Dan and Chloe to speculate on the painful effect of childhood problems without suggesting specific ways to change their behavior. But Young began his career in the early '80s as a new therapy was gaining popularity—cognitive therapy, which teaches that how people think about events in their lives determines how they feel about them. Young, who studied with the man behind the therapy, Aaron T. Beck, was excited to be a part of a dynamic new method. But early on, he found that this approach alone was not enough to help clients with lifelong relationship troubles. "It was fine with people who'd been healthy and had problems only recently, but the majority of patients had problems that stemmed from their early life, and those people didn't respond well," he says.

Young began to spot a number of distinct, recurring patterns in his patients' psychological profiles—patterns laid down in early childhood that continued to shape their adult thoughts, actions, relationships, careers, and life choices. He called these habits "schemas," borrowing the ancient Greek word for "form," and he nicknamed them "lifetraps" to make it easier for his clients to understand both the concept and the risk of letting their schemas define them.

Although schema therapy began as an individual therapeutic strategy, it quickly turned into a couples therapy technique. "More than half the people we saw were coming in with problems with their relationship," Young says. "We thought, 'What if we got the partner in?' Once we did, we began to notice there was an interplay between them that was creating problems. One partner's schema would trigger the other's schema, and tensions would escalate." Some of the schemas dovetail—in a catastrophic way—each exacerbating the other. In fact, Young says, head-over-heels romantic attraction is often a sign of bad schema chemistry.

Young suspected that Dan suffered from the Defectiveness schema, which means that, when he was a child, his peers or family put him down, criticized him, and made him feel inferior. By asking questions in further sessions, he learned that Dan's mother favored his older brother and his father told him he was incompetent.

Chloe, on the other hand, was plagued by Unrelenting Standards. As a child, her family made her feel that, unless she was completely above reproach, she was a total failure. These are two of the 18 schemas Young has identified; a person may be affected or defined by any number of schemas—just as in astrology, people speak of an Aries who has a Cancer moon and Virgo rising. For instance, a patient may have the core schema of Emotional Deprivation and also be affected by the Abandonment and Self-Sacrifice schemas. (Take a quiz on common schemas.)

Young's work has a curious parallel with recent developments in the field of interpersonal neurobiology, which suggest that our personal relationships affect the way the mind builds neural pathways. Your emotional memories—of a parent you adored or feared, of a partner you loved or lost—create pathways in the limbic part of the brain. Every time you revisit those memories, positive or negative, you reinforce the path, deepening a trench of emotional connection. Throughout life, your unconscious mind embraces any new person who reminds you of those older paths. They exert an almost irresistible pull, compelling you to make decisions that feel like choices but are actually automatic responses guided by the map of your past: It's like a ghost road that lures in passers-by. "We think what we call schemas are really what some people call neural pathways," Young says. People who want healthy relationships but have a history of unhealthy ones must work hard to resist the pull of habit and strike out along new pathways, literally and figuratively.

Young's first step is to help his patients recognize that they have schemas: "They've affected their view of everything," says Young. "But they don't see that there's anything wrong with the way they look at the world." He began by asking Chloe about her parents. She described them as high-level professionals who had been extremely critical of her. If she came home with an A- instead of an A+, for instance, her mother would withdraw her affection for a week, withholding kisses and kindness.

"I tried to get Chloe to remember what it felt like when her mother would withdraw from her and to remember how bad she felt about herself," Young says. As an adult, Chloe remained stuck in her schema, clinging stubbornly to her childhood fear that if she or anyone she was associated with was less than perfect, she would be a disappointment. Young knew that she had internalized her parents' harsh judgments and was not aware they weren't her own. His questions helped her make the connection that the way her mother hurt her was the way she hurt the men in her life—at which point, Chloe got it, saying, "I don't want to make Dan feel the way I felt."

Young also helped Dan realize that he was repeating his unhappy childhood cycle with Chloe: trying to prove that he was good enough. Young spent the next several sessions helping Chloe and Dan understand that when they upset each other, it was not out of deliberate cruelty but often because one partner had set off the other's core schemas.

"Chloe had to become more aware of when her Unrelenting Standards were being triggered, making her critical and mean," Young says. "Dan had to become aware of when he was starting to feel inadequate and trying to prove himself to her." When a fight began to escalate, Young instructed, they should say out loud, "Schema clash!"—as unnatural as it might feel—and then call a time-out. They should retreat into separate rooms and read through a flash card to remind them of the havoc their schemas were trying to unleash (Young helps couples create a variety of notes, tailored to common issues of discord—arguments over money or parenting, for example). A card for Chloe might read in part:

Even though I feel as if my criticisms are valid, it's almost certain that I'm being much too hard on Dan and too judgmental, the same way my mother was with me. Therefore I need to let up on him, stop criticizing him, and apologize for what I did.

Young's first step is to help his patients recognize that they have schemas: "They've affected their view of everything," says Young. "But they don't see that there's anything wrong with the way they look at the world." He began by asking Chloe about her parents. She described them as high-level professionals who had been extremely critical of her. If she came home with an A- instead of an A+, for instance, her mother would withdraw her affection for a week, withholding kisses and kindness.

"I tried to get Chloe to remember what it felt like when her mother would withdraw from her and to remember how bad she felt about herself," Young says. As an adult, Chloe remained stuck in her schema, clinging stubbornly to her childhood fear that if she or anyone she was associated with was less than perfect, she would be a disappointment. Young knew that she had internalized her parents' harsh judgments and was not aware they weren't her own. His questions helped her make the connection that the way her mother hurt her was the way she hurt the men in her life—at which point, Chloe got it, saying, "I don't want to make Dan feel the way I felt."

Young also helped Dan realize that he was repeating his unhappy childhood cycle with Chloe: trying to prove that he was good enough. Young spent the next several sessions helping Chloe and Dan understand that when they upset each other, it was not out of deliberate cruelty but often because one partner had set off the other's core schemas.

"Chloe had to become more aware of when her Unrelenting Standards were being triggered, making her critical and mean," Young says. "Dan had to become aware of when he was starting to feel inadequate and trying to prove himself to her." When a fight began to escalate, Young instructed, they should say out loud, "Schema clash!"—as unnatural as it might feel—and then call a time-out. They should retreat into separate rooms and read through a flash card to remind them of the havoc their schemas were trying to unleash (Young helps couples create a variety of notes, tailored to common issues of discord—arguments over money or parenting, for example). A card for Chloe might read in part:

Even though I feel as if my criticisms are valid, it's almost certain that I'm being much too hard on Dan and too judgmental, the same way my mother was with me. Therefore I need to let up on him, stop criticizing him, and apologize for what I did.

Young admits this technique can seem awkward in the beginning. As therapy progresses and communication improves, the flash cards can be left behind. "Eventually, the partners catch their pattern much more quickly, and they don't have to have time-outs," Young says. They can head off the conflict before it arises. "When therapy is successful, it doesn't mean the schema inside each person isn't being triggered," he says. "But they learn that they don't need to let it out." As patients come to recognize their schemas, they realize that, although they are not entirely to blame for their strong feelings, they are responsible for learning to control them better.

Schema therapy saved Chloe and Dan's relationship. "We have a very high success rate with couples like this," Young says. Both partners genuinely wanted to change, and, still more important, both of them were willing to accept the idea that there was something wrong with their behavior. (Young estimates schema therapy succeeds with about 70 percent of couples he and his colleagues see.)

Those who have benefited from schema therapy have one thing in common: They felt the thrill and relief of learning that there was a name for the impulses that had directed their actions for so long. They could see there was a more accurate explanation for the unhealthy patterns in their lives and relationships than the one they'd been telling themselves. They stepped back from their lifetraps and studied the map of their behavior. And slowly, but perseveringly, they dared to set out on a different course, with a new understanding not only of the direction they wanted to take but of themselves.

Keep Reading: Which schemas do you fall into?

Schema therapy saved Chloe and Dan's relationship. "We have a very high success rate with couples like this," Young says. Both partners genuinely wanted to change, and, still more important, both of them were willing to accept the idea that there was something wrong with their behavior. (Young estimates schema therapy succeeds with about 70 percent of couples he and his colleagues see.)

Those who have benefited from schema therapy have one thing in common: They felt the thrill and relief of learning that there was a name for the impulses that had directed their actions for so long. They could see there was a more accurate explanation for the unhealthy patterns in their lives and relationships than the one they'd been telling themselves. They stepped back from their lifetraps and studied the map of their behavior. And slowly, but perseveringly, they dared to set out on a different course, with a new understanding not only of the direction they wanted to take but of themselves.

Keep Reading: Which schemas do you fall into?

People tend to relate to one or more of these 18 schemas. Which schema or schemas sound familiar to you?

Abandonment

People who cling to others because they're afraid of being left and don't feel important relationships will last. They're usually attracted to partners who cannot be there in a committed way.

Emotional Deprivation

Most of the time, these patients haven't had someone to nurture them, to care deeply about everything that happens to them or someone who was tuned in to their true feelings and needs.

Entitlement

Those who hate to be constrained or kept from doing what they want or feel that they shouldn't have to follow the normal rules and conventions other people do.

Defectiveness

People who think they're unworthy of the love, attention, and respect of others and believe that no matter how hard they try, they won't be able to get a significant partner to respect them or feel they are worthwhile.

Subjugation

In relationships, these people let the other person have the upper hand and worry a lot about pleasing other people so they won't be rejected.

Unrelenting Standards

People who must be the best at most of what they do and feel there is constant pressure to achieve and get things done. Their relationships suffer because they push themselves so hard.

Mistrust/Abuse

Those who feel that they cannot let their guard down in the presence of other people, or else that person will intentionally hurt them. If someone acts nicely toward them, they assume that he/she must be after something.

Self-Sacrifice

People who puts others' needs before their own, or else they feel guilty, and usually end up taking care of the people they're close to.

Social Isolation

Individuals who don't think that they relate well to other people and/or feel that they don't fit in with any sort of group.

Dependence

People who often feel helpless or aren't capable of making a decision without the aid of another person.

Vulnerability to Harm or Illness

Hypochondriacs and/or those who consistently fear that they will be involved in a catastrophe like an airplane crash or hurricane.

Enmeshment

Young's patients who have a weak sense of personal identity and habitually cling to or "mesh" with other people do so in order to feel like a complete person.

Failure

Someone who believes they will never succeed or that they're not as bright or talented as the people around them.

Insufficient Self-Control

Those who lack self-discipline and want to quit a task at the first sign of frustration or failure. (People with milder forms of this schema will give up personal satisfaction or fulfillment in order to avoid conflict or confrontation; could be described as a slacker.)

Approval Seeking

Individuals can place an extreme importance on other people's opinions and sometimes put a high level of significance on appearance and social status as a means to get attention.

Negativity

Someone who focuses on the worst parts of life (disappointments, missteps, and embarrassing moments) and might have inflated fears that they will make a mistake that will result in a personal crisis, like financial ruin.

Inhibition

People who are afraid to show emotion or, for that matter, initiate conversation—might be described as wallflowers.

Punitiveness

Those that believe even the smallest mistake deserves punishment. Usually hold themselves—and others—to very high expectations; find it hard to empathize or forgive mistakes, their own and those of others.

Keep Reading

Abandonment

People who cling to others because they're afraid of being left and don't feel important relationships will last. They're usually attracted to partners who cannot be there in a committed way.

Emotional Deprivation

Most of the time, these patients haven't had someone to nurture them, to care deeply about everything that happens to them or someone who was tuned in to their true feelings and needs.

Entitlement

Those who hate to be constrained or kept from doing what they want or feel that they shouldn't have to follow the normal rules and conventions other people do.

Defectiveness

People who think they're unworthy of the love, attention, and respect of others and believe that no matter how hard they try, they won't be able to get a significant partner to respect them or feel they are worthwhile.

Subjugation

In relationships, these people let the other person have the upper hand and worry a lot about pleasing other people so they won't be rejected.

Unrelenting Standards

People who must be the best at most of what they do and feel there is constant pressure to achieve and get things done. Their relationships suffer because they push themselves so hard.

Mistrust/Abuse

Those who feel that they cannot let their guard down in the presence of other people, or else that person will intentionally hurt them. If someone acts nicely toward them, they assume that he/she must be after something.

Self-Sacrifice

People who puts others' needs before their own, or else they feel guilty, and usually end up taking care of the people they're close to.

Social Isolation

Individuals who don't think that they relate well to other people and/or feel that they don't fit in with any sort of group.

Dependence

People who often feel helpless or aren't capable of making a decision without the aid of another person.

Vulnerability to Harm or Illness

Hypochondriacs and/or those who consistently fear that they will be involved in a catastrophe like an airplane crash or hurricane.

Enmeshment

Young's patients who have a weak sense of personal identity and habitually cling to or "mesh" with other people do so in order to feel like a complete person.

Failure

Someone who believes they will never succeed or that they're not as bright or talented as the people around them.

Insufficient Self-Control

Those who lack self-discipline and want to quit a task at the first sign of frustration or failure. (People with milder forms of this schema will give up personal satisfaction or fulfillment in order to avoid conflict or confrontation; could be described as a slacker.)

Approval Seeking

Individuals can place an extreme importance on other people's opinions and sometimes put a high level of significance on appearance and social status as a means to get attention.

Negativity

Someone who focuses on the worst parts of life (disappointments, missteps, and embarrassing moments) and might have inflated fears that they will make a mistake that will result in a personal crisis, like financial ruin.

Inhibition

People who are afraid to show emotion or, for that matter, initiate conversation—might be described as wallflowers.

Punitiveness

Those that believe even the smallest mistake deserves punishment. Usually hold themselves—and others—to very high expectations; find it hard to empathize or forgive mistakes, their own and those of others.

Keep Reading