Want to be one of life's winners? Stop trying! You'll be a lot healthier, maybe wealthier, and altogether happier if you learn the glory in giving up.

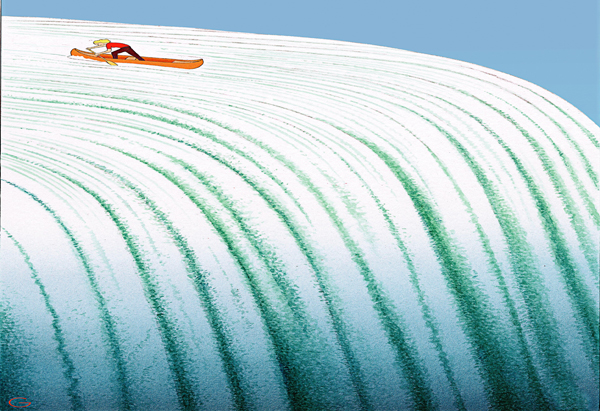

Illustration by Guy Billout

I call my friend Betsy "Best-y" for two reasons: first, because she's one of the best-beloved people in my life, and second, because anything she tries, she does better than anyone else in the world. The one thing that occasionally ruffles our mutual affection is that we're both rather competitive, in the sense that if you wondered aloud which of us could most quickly remove her own gall bladder with kitchen implements, Besty and I would be fighting for steak knives before the words left your mouth.

That doesn't bother me, though, because I'm less competitive than Besty. If someone were to rank us on noncompetitiveness, I would definitely win.

Anyway, one January—resolution time, goal time, gotta-shed-holiday-weight time—Besty and I joined some pals at a spa, planning to refocus, get in shape, prove that when the going gets tough, the tough get going. Instead, that week taught me to honor W.C. Fields's profound statement "If at first you don't succeed, try again. Then quit. No use being a damn fool about it." The thing is, science supports this. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the ability to quit easily makes us healthier—and wealthier—than does leechlike tenacity.

After settling in at the spa, Besty and I considered the activities being offered the following day.

"Oh, look!" said Besty. "There's a morning hike at 5 a.m.!"

"Great!" I said, trying not to show horror. If Besty could haul herself out of bed and frolic athletically in the middle of the night, then, dammit, so could I.

"We'll be back in time for water aerobics," said Besty. "And after that, weight training and then kickboxing. This'll be so fun!"

"Fun!" I echoed. Then I heard my own voice, like a train with no brakes, saying, "How about Pilates and Jazzercise after that?"

"Cool!" said Besty. "I'm in!"

Dammit!

The next day was a blur of sweaty, exhausting, recondite competition. Besty walked faster than I did on the hike, because I'm not a morning person. Then I edged her out in weight training. Kickboxing was a draw—her kicks were higher, but she's tall, which must be considered. Besty got more praise from the Pilates coach, but I got more in Jazzercise. After seven straight hours of strenuous exercise, I felt as though my muscles had been taken apart, scoured, then badly reassembled by a team of evil student nurses. Besty still looked fresh. Pert. She looked really pert.

"Ready to call it a day?" I asked.

"Well..." Besty said. "There's still an advanced yoga class before dinner."

I looked at my schedule. Dammit! Dammit! Dammit!

"Shall we?" asked Besty, like a kid on Christmas morning.

"Absolutely!" I gagged. "Wouldn't miss it!" That class lasted approximately as long as the Pleistocene epoch. I try never to think of it. Sometimes, though, despite heavy medication, the memory returns unbidden, and I hear again the yoga instructor's comment, "The key to success is persistence. Quitting is failure." My mind reacted to this with numb acquiescence—I'd heard it so often, after all. But my body silently screamed, "Not always!"

Turns out my body was right.

That doesn't bother me, though, because I'm less competitive than Besty. If someone were to rank us on noncompetitiveness, I would definitely win.

Anyway, one January—resolution time, goal time, gotta-shed-holiday-weight time—Besty and I joined some pals at a spa, planning to refocus, get in shape, prove that when the going gets tough, the tough get going. Instead, that week taught me to honor W.C. Fields's profound statement "If at first you don't succeed, try again. Then quit. No use being a damn fool about it." The thing is, science supports this. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the ability to quit easily makes us healthier—and wealthier—than does leechlike tenacity.

Quitters Win and Winners Quit

After settling in at the spa, Besty and I considered the activities being offered the following day.

"Oh, look!" said Besty. "There's a morning hike at 5 a.m.!"

"Great!" I said, trying not to show horror. If Besty could haul herself out of bed and frolic athletically in the middle of the night, then, dammit, so could I.

"We'll be back in time for water aerobics," said Besty. "And after that, weight training and then kickboxing. This'll be so fun!"

"Fun!" I echoed. Then I heard my own voice, like a train with no brakes, saying, "How about Pilates and Jazzercise after that?"

"Cool!" said Besty. "I'm in!"

Dammit!

The next day was a blur of sweaty, exhausting, recondite competition. Besty walked faster than I did on the hike, because I'm not a morning person. Then I edged her out in weight training. Kickboxing was a draw—her kicks were higher, but she's tall, which must be considered. Besty got more praise from the Pilates coach, but I got more in Jazzercise. After seven straight hours of strenuous exercise, I felt as though my muscles had been taken apart, scoured, then badly reassembled by a team of evil student nurses. Besty still looked fresh. Pert. She looked really pert.

"Ready to call it a day?" I asked.

"Well..." Besty said. "There's still an advanced yoga class before dinner."

I looked at my schedule. Dammit! Dammit! Dammit!

"Shall we?" asked Besty, like a kid on Christmas morning.

"Absolutely!" I gagged. "Wouldn't miss it!" That class lasted approximately as long as the Pleistocene epoch. I try never to think of it. Sometimes, though, despite heavy medication, the memory returns unbidden, and I hear again the yoga instructor's comment, "The key to success is persistence. Quitting is failure." My mind reacted to this with numb acquiescence—I'd heard it so often, after all. But my body silently screamed, "Not always!"

Turns out my body was right.

Recently, psychologists Gregory Miller and Carsten Wrosch set out to investigate the mental and physical health of people who resist quitting, and of those who throw in the towel when facing unattainable goals. The second group—the quitters—were healthier than their persistent peers on almost every variable. They suffered fewer health problems, from digestive trouble to rashes, and showed fewer signs of psychological stress.

In another study, which followed a group of teenagers for a year, subjects who quit easily had much lower levels of a protein linked to inflammation than did their more tenacious peers. This made them less likely to develop many debilitating illnesses later in life.

The mechanism that helps people quit appropriately, Miller and Wrosch discovered, was not wisdom but dejection. People who are trying in vain eventually get depressed about their ongoing failure, and those who respond to this depression by quitting when it first appears enjoy all kinds of benefits.

I didn't think about this scientifically during that yoga class—though I experienced it subjectively when the teacher guided us into a shoulder stand. The pose caused my body to quake violently with exhaustion as my workout shorts fell back around my pelvis and my gaze was forced upward. Gentle reader, you cannot imagine a ghastlier view: The depression evoked by the gelatinous consistency of my thighs beggars description.

I should've quit right then. I would have, if Besty weren't so competitive.

The fact that I continued with the class exemplifies my approach to life and no doubt explains my digestive troubles, rashes, and inflammatory illnesses. But the implications don't stop there: Not quitting may be at the root of fiscal problems as well as physical ones. That's right—quitters prosper not only physically but financially.

Every first-year economics student learns about the "sunk-cost fallacy," though virtually no one remembers it when making spending choices. The sunk-cost fallacy is a universal human error. It refers to our tendency to throw good money after bad, trying to justify our mistakes by devoting more resources to them. For example, a gambler who's lost a small fortune is likely to stay and keep hemorrhaging cash precisely because he's losing. "I'm down $10,000," the thinking goes. "I have to keep playing until I get it back—this rotten luck can't go on forever." This is how human psychology works.

It is not how reality works.

A gambler is no more likely to win on the 500th roulette spin than on any of the previous 499. But a huge amount of effort goes into attempts at redeeming things—lemon cars, money–pit houses, horrible relationships, wars—that just aren't working. Learning to quit while you're not ahead, when the dull ooze of depression tells you things are not going to get any better, is one of the best financial and life skills you can master.

This should have occurred to me well before Besty and I hit that yoga studio. It should have occurred to me several years earlier, when I first realized that she was simply better than I was at everything. But even after a thousand failed attempts—and even though I once actually taught at a business school—I forged on.

Moving from shoulder stand to triangle pose, I was hit by two things: a back spasm and the realization that though I was ready to quit, I didn't know how. I'd never practiced quitting. I didn't know the right path out of the room, the right facial expression, the right way to give up.

So there I stood, befuddled, trying to touch my right foot with my right hand while bending sideways, when I heard a complicated thumping from the other side of the studio. By rolling my eyes far back into my skull, I saw what had made the sound. Besty had toppled from triangle pose directly into corpse pose.

She seemed too tired to speak, but from her feeble movements, she might have been trying to signal something—perhaps that she wished to be rinsed. But I took my own message from her example. In that moment, I saw with great clarity that (to paraphrase poet Elizabeth Bishop) the art of quitting isn't hard to master. We can always just go limp.

In another study, which followed a group of teenagers for a year, subjects who quit easily had much lower levels of a protein linked to inflammation than did their more tenacious peers. This made them less likely to develop many debilitating illnesses later in life.

The mechanism that helps people quit appropriately, Miller and Wrosch discovered, was not wisdom but dejection. People who are trying in vain eventually get depressed about their ongoing failure, and those who respond to this depression by quitting when it first appears enjoy all kinds of benefits.

I didn't think about this scientifically during that yoga class—though I experienced it subjectively when the teacher guided us into a shoulder stand. The pose caused my body to quake violently with exhaustion as my workout shorts fell back around my pelvis and my gaze was forced upward. Gentle reader, you cannot imagine a ghastlier view: The depression evoked by the gelatinous consistency of my thighs beggars description.

I should've quit right then. I would have, if Besty weren't so competitive.

The Quitting Bonus

The fact that I continued with the class exemplifies my approach to life and no doubt explains my digestive troubles, rashes, and inflammatory illnesses. But the implications don't stop there: Not quitting may be at the root of fiscal problems as well as physical ones. That's right—quitters prosper not only physically but financially.

Every first-year economics student learns about the "sunk-cost fallacy," though virtually no one remembers it when making spending choices. The sunk-cost fallacy is a universal human error. It refers to our tendency to throw good money after bad, trying to justify our mistakes by devoting more resources to them. For example, a gambler who's lost a small fortune is likely to stay and keep hemorrhaging cash precisely because he's losing. "I'm down $10,000," the thinking goes. "I have to keep playing until I get it back—this rotten luck can't go on forever." This is how human psychology works.

It is not how reality works.

A gambler is no more likely to win on the 500th roulette spin than on any of the previous 499. But a huge amount of effort goes into attempts at redeeming things—lemon cars, money–pit houses, horrible relationships, wars—that just aren't working. Learning to quit while you're not ahead, when the dull ooze of depression tells you things are not going to get any better, is one of the best financial and life skills you can master.

This should have occurred to me well before Besty and I hit that yoga studio. It should have occurred to me several years earlier, when I first realized that she was simply better than I was at everything. But even after a thousand failed attempts—and even though I once actually taught at a business school—I forged on.

How to Quit

Moving from shoulder stand to triangle pose, I was hit by two things: a back spasm and the realization that though I was ready to quit, I didn't know how. I'd never practiced quitting. I didn't know the right path out of the room, the right facial expression, the right way to give up.

So there I stood, befuddled, trying to touch my right foot with my right hand while bending sideways, when I heard a complicated thumping from the other side of the studio. By rolling my eyes far back into my skull, I saw what had made the sound. Besty had toppled from triangle pose directly into corpse pose.

She seemed too tired to speak, but from her feeble movements, she might have been trying to signal something—perhaps that she wished to be rinsed. But I took my own message from her example. In that moment, I saw with great clarity that (to paraphrase poet Elizabeth Bishop) the art of quitting isn't hard to master. We can always just go limp.

That's something any toddler intuitively knows. For instance, when my daughter Katie was 3, she said she'd just met "that fat lady next door." I told her that was wonderful, except that it was better to refer to "the fat lady" as Mrs. Ellis.

"What if I forget?" Katie asked.

"Well, honey, then I'll remind you."

Katie thought for a minute and asked, "What if I refuse?"

That, frankly, was a stumper. I had no real way to force my daughter—or anyone else—to continue doing something she simply refused to do.

So, how do you quit doing something when depression, inflammation, and financial disaster loom? If worst comes to worst, just stop. The formalities will take care of themselves. I'm not advocating this, but if you stop showing up at work, they'll fire you. If you refuse to act married, your spouse will eventually drift away or file for divorce. It's far better karma to be up-front and honorable about quitting. I'm just pointing out that you always have the power to quit something at a physical level. In other words: Corpse pose is always an option.

This applies to everything, including (stay with me here) the process of quitting itself. If you're trying in vain to quit something you do compulsively, like overspending or smoking or macramé, try quitting the effort to quit. As therapists like to say, "What we resist, persists," and this is especially true of bad habits. Imagine trying not to eat one sinfully delicious chocolate truffle. Got it? Okay, now imagine trying to eat 10,000 truffles at one sitting. For most of us, the thought of not-quitting in this enormous way—indulging ourselves beyond desire—actually dampens the appetite. It's a counterintuitive method, but if the "I will abstain from..." resolutions you make each year are utter, depressing failures, you might quit quitting and see what happens. When my clients stop unsuccessful efforts to quit, they often experience such a sense of relief and empowerment that quitting becomes easier—it's paradoxical but true. (Try it before you dismiss it.)

I didn't know what made Besty hit the floor of the yoga studio. I assumed she'd simply misplaced her center of gravity, due to having lost so much weight in one day. But I was wrong. She'd had enough—and her giving in to the force of gravity had a liberating effect on me. I found myself shuffling toward the door, and as I did, my depression lightened. I'd stumbled across a transformative resolution I'd keep all that year: to quit when I was behind, without shame or self-recrimination. It was a watershed moment in my life and in my friendship with Besty. She was fitter and more determined than I was, and even when it came to quitting, my friend had done the job first, and best.

Dammit.

More Martha Beck Advice

"What if I forget?" Katie asked.

"Well, honey, then I'll remind you."

Katie thought for a minute and asked, "What if I refuse?"

That, frankly, was a stumper. I had no real way to force my daughter—or anyone else—to continue doing something she simply refused to do.

So, how do you quit doing something when depression, inflammation, and financial disaster loom? If worst comes to worst, just stop. The formalities will take care of themselves. I'm not advocating this, but if you stop showing up at work, they'll fire you. If you refuse to act married, your spouse will eventually drift away or file for divorce. It's far better karma to be up-front and honorable about quitting. I'm just pointing out that you always have the power to quit something at a physical level. In other words: Corpse pose is always an option.

This applies to everything, including (stay with me here) the process of quitting itself. If you're trying in vain to quit something you do compulsively, like overspending or smoking or macramé, try quitting the effort to quit. As therapists like to say, "What we resist, persists," and this is especially true of bad habits. Imagine trying not to eat one sinfully delicious chocolate truffle. Got it? Okay, now imagine trying to eat 10,000 truffles at one sitting. For most of us, the thought of not-quitting in this enormous way—indulging ourselves beyond desire—actually dampens the appetite. It's a counterintuitive method, but if the "I will abstain from..." resolutions you make each year are utter, depressing failures, you might quit quitting and see what happens. When my clients stop unsuccessful efforts to quit, they often experience such a sense of relief and empowerment that quitting becomes easier—it's paradoxical but true. (Try it before you dismiss it.)

I didn't know what made Besty hit the floor of the yoga studio. I assumed she'd simply misplaced her center of gravity, due to having lost so much weight in one day. But I was wrong. She'd had enough—and her giving in to the force of gravity had a liberating effect on me. I found myself shuffling toward the door, and as I did, my depression lightened. I'd stumbled across a transformative resolution I'd keep all that year: to quit when I was behind, without shame or self-recrimination. It was a watershed moment in my life and in my friendship with Besty. She was fitter and more determined than I was, and even when it came to quitting, my friend had done the job first, and best.

Dammit.

More Martha Beck Advice