They're footballers. Fraternity men. Big, burly guys like ex-quarterback Don McPherson, who's hoping to lead a new generation of men into a violence-free end zone.

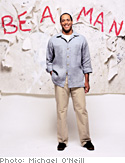

Several New York Dragons football players limp into the room with what Don McPherson calls the midseason walk, meaning they have weeks of scrapes and bruises that haven't yet had a chance to heal. They reach out to shake Don's hand and the contrast is dramatic. The Dragons—members of a professional arena (indoor) football team—have their injuries, their baggy clothes, and their faint hopes for a future in the National Football League, while the 37-year-old Don has already had his dash in the NFL, his injuries have long since healed, and his crisp khaki pants, lapis-blue shirt, and easy smile make him look like a corporate executive on retreat. Still, Don will be mining the similarities between himself and these men in his presentation—not just their shared experience in football but also their shared history as men in a country where sexual violence runs rampant. A country in which, experts estimate, a woman is battered by a man—usually an intimate partner—every 15 seconds, raped every two minutes, and murdered by a spouse or boyfriend every six hours."Let's look at the semantics of sexism," Don begins, writing on a whiteboard. The Dragons lean forward intently, as if he's a coach outlining strategy for an upcoming game. Then he stands back and reads these words aloud.

Jack beats Jill.

Jill was beaten by Jack.

Jill was beaten.

Jill is a battered woman.

"What's happened here?" Don asks, pointing his marker at the last line. After a few seconds, one of the players speaks up. "Jack's missing?" Don nods. "Jack is out of the picture and Jill is stigmatized. That shows that even our language about sexual violence blames women for the things that men do."

The Dragons pay rapt attention for the next two hours, not only because this is a startling concept but because Don cuts a heroic figure. As a quarterback at Syracuse University, he was first in the NCAA in passing and led Syracuse to an undefeated season in 1987. He won more than 18 national collegiate-player-of-the-year honors, then played for the Philadelphia Eagles and Houston Oilers before retiring in 1994.

This kind of career isn't just a dream for arena football players, of course—many men have such dreams and idolize the men who achieve them. Whenever Don would return to his hometown during his football years, old acquaintances were quick to cluster around him. "You still playing football?" they'd crow. "You the man!" But it's in the eight years since he left football that Don has emerged as a real hero. He's parlayed his superstar credibility into speaking engagements with thousands of people—especially male athletes and college students—to talk about sexual violence, male privilege, and the culture that breeds them.

For some 30 years, activists—mostly women—have struggled to provide services to victims of sexual violence, pressure the criminal justice system to punish offenders, and drag sexual violence into the court of public censure. In the past few years, there's been a dazzling explosion of new energy in this movement as a small but growing number of men like Don McPherson join the fray. "Daily violence is a part of our culture—school shootings, the Oklahoma City bombing," Don tells the Dragons. "Does it ever occur to any of us that girls are doing it? No. What about rape, sexual assault, harassment, date rape, domestic violence—if we call these things women's issues, what does that allow men to do? That's right, take no responsibility for it. We are the perpetrators." In the process of challenging other men to take responsibility for male behavior, male activists like Don are taking on the whole structure of sexism—gender prejudice plus power—that encourages such crimes. Many even call themselves feminists.

"I use the f-word a lot," says Mark Wynn, a former Nashville police lieutenant and another sexual violence missionary who educates medical, social service, and criminal justice professionals around the world about the dynamics of domestic violence. Mark can describe the powerlessness felt by victims firsthand: His own mother endured years of escalating abuse but was too terrified, isolated, and ashamed to leave her abuser. "My definition of a feminist is someone who protects the rights of women, so I'm proud of this," Mark says. "I think all of us should be feminists."

Certainly, some men have toiled against sexual violence in the past, but their numbers have been tiny and they've been concentrated in academia or social work. This new wave of male activists is not only much bigger but their backgrounds allow them to wield a different kind of clout: men like Don and Mark, for instance, who hail from traditional male bastions and have lived the kind of rough-and-tumble masculinity so admired by other men. When "real men" like these blast long-cherished sexually aggressive male behaviors, other men tend to take notice.

Some male activists are in the entertainment industry and use their showbiz glitter to highlight male violence: men like country rocker Andy Griggs, a national spokesperson for the Family Violence Prevention Fund, who recorded "Waitin' On Sundown," a song about a woman fleeing an abusive spouse. "You hear a lot of women talk about sexual violence, but not men. It's time for men to stand up and say, 'I will not abuse women and I will not support violence against them.'"

For some 30 years, activists—mostly women—have struggled to provide services to victims of sexual violence, pressure the criminal justice system to punish offenders, and drag sexual violence into the court of public censure. In the past few years, there's been a dazzling explosion of new energy in this movement as a small but growing number of men like Don McPherson join the fray. "Daily violence is a part of our culture—school shootings, the Oklahoma City bombing," Don tells the Dragons. "Does it ever occur to any of us that girls are doing it? No. What about rape, sexual assault, harassment, date rape, domestic violence—if we call these things women's issues, what does that allow men to do? That's right, take no responsibility for it. We are the perpetrators." In the process of challenging other men to take responsibility for male behavior, male activists like Don are taking on the whole structure of sexism—gender prejudice plus power—that encourages such crimes. Many even call themselves feminists.

"I use the f-word a lot," says Mark Wynn, a former Nashville police lieutenant and another sexual violence missionary who educates medical, social service, and criminal justice professionals around the world about the dynamics of domestic violence. Mark can describe the powerlessness felt by victims firsthand: His own mother endured years of escalating abuse but was too terrified, isolated, and ashamed to leave her abuser. "My definition of a feminist is someone who protects the rights of women, so I'm proud of this," Mark says. "I think all of us should be feminists."

Certainly, some men have toiled against sexual violence in the past, but their numbers have been tiny and they've been concentrated in academia or social work. This new wave of male activists is not only much bigger but their backgrounds allow them to wield a different kind of clout: men like Don and Mark, for instance, who hail from traditional male bastions and have lived the kind of rough-and-tumble masculinity so admired by other men. When "real men" like these blast long-cherished sexually aggressive male behaviors, other men tend to take notice.

Some male activists are in the entertainment industry and use their showbiz glitter to highlight male violence: men like country rocker Andy Griggs, a national spokesperson for the Family Violence Prevention Fund, who recorded "Waitin' On Sundown," a song about a woman fleeing an abusive spouse. "You hear a lot of women talk about sexual violence, but not men. It's time for men to stand up and say, 'I will not abuse women and I will not support violence against them.'"