Start Something Big

Sister Act

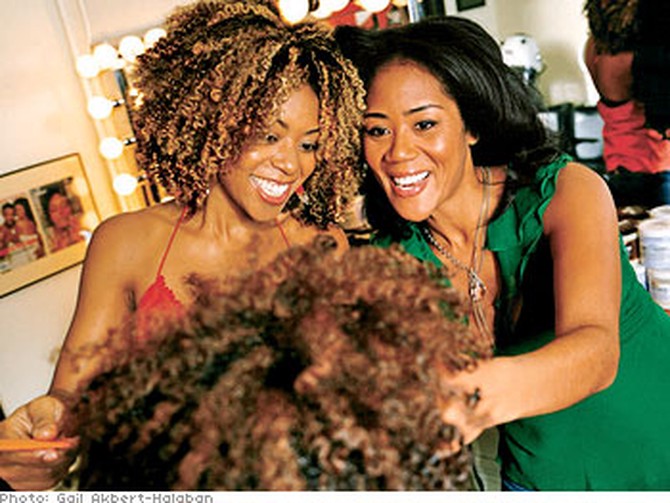

Titi and Miko Branch, Curve Salon

Titi and Miko Branch have a Japanese mother, an African-American father, and hair that defies easy description. "It's not kinky, it's not straight," Titi says. "It's multitextured." Managing their curls and waves has been a lifelong challenge, but the sisters got help early on from their paternal grandmother, Miss Jessie, who mixed homemade treatments for them made of eggs, castor oil and other ingredients. In 1997, Titi and Miko opened a salon in Brooklyn to cater to people with hair like theirs.

Sweat equity: "When we opened Curve Salon, we used our savings and did all the renovation work ourselves—stripping the floors, sanding them, plastering and painting," says Miko.

Present perfect: "We're a small operation: We have fewer than ten employees, and we see 15 to 20 clients every day," says Titi. "We're taking baby steps. We've learned that you want to grow at a rate you can handle."

The last resort: "Our salon is really a forum for sharing information. Most people come to us with a problem, and some of them come in with a notebook full of specific questions on how to manage their curly, kinky, or wavy hair," says Titi. "So in 1999, when we decided to really focus on those people, we became appointment only. We consult with each person—it's almost like a doctor's office."

Titi and Miko Branch, Curve Salon

Titi and Miko Branch have a Japanese mother, an African-American father, and hair that defies easy description. "It's not kinky, it's not straight," Titi says. "It's multitextured." Managing their curls and waves has been a lifelong challenge, but the sisters got help early on from their paternal grandmother, Miss Jessie, who mixed homemade treatments for them made of eggs, castor oil and other ingredients. In 1997, Titi and Miko opened a salon in Brooklyn to cater to people with hair like theirs.

Sweat equity: "When we opened Curve Salon, we used our savings and did all the renovation work ourselves—stripping the floors, sanding them, plastering and painting," says Miko.

Present perfect: "We're a small operation: We have fewer than ten employees, and we see 15 to 20 clients every day," says Titi. "We're taking baby steps. We've learned that you want to grow at a rate you can handle."

The last resort: "Our salon is really a forum for sharing information. Most people come to us with a problem, and some of them come in with a notebook full of specific questions on how to manage their curly, kinky, or wavy hair," says Titi. "So in 1999, when we decided to really focus on those people, we became appointment only. We consult with each person—it's almost like a doctor's office."

One Smart Cookie

Debbie Godowsky, Cookies Direct

Godowsky liked being a stay-at-home mom and substitute teacher in Yarmouth, Maine, but in 1991, when her children were in the fifth and eighth grades, she realized she'd have to start earning serious money so that she and her husband could afford to send their kids to college.

A sweet idea: "I was substitute-teaching a study hall for seniors at the high school, and I asked them if they had any ideas for a home business. They said, 'Why don't you do cookie care packages for kids in college?' It seemed like a good idea. I called our state's small business administration—every state has one—and they said for $4 they could send me a packet on how to start a business. I brought cookies to school and tested my recipes on the students. By summer I was taking orders, and in September we started shipping."

Word of mouth: "Right away I thought, How can we get the parents to buy more than one box of cookies? How about a cookie-of-the-month club? Before long, some of them said, 'I know you've been sending cookies to my child, but can you do client gifts?'"

Kitchen aid: "I couldn't make all the cookies in my own kitchen, and I didn't want to pay for an expensive industrial mixer, so I called a local restaurant that served only lunch and dinner and asked if I could use their mixer in the mornings. They said yes. After a year, I bought a mixer—used. I'm a firm believer in saving money where you can. Now we ship about 250 dozen cookies a week."

Sugar, spice and the bottom line: "A lot of people try to turn something they love to do into a business—let's say, baking pies or dog walking. But I went at it from the opposite end: I thought, What I'd love is to run a business—what will make it work? I didn't love baking cookies—I loved being able to send my kids to college."

Debbie Godowsky, Cookies Direct

Godowsky liked being a stay-at-home mom and substitute teacher in Yarmouth, Maine, but in 1991, when her children were in the fifth and eighth grades, she realized she'd have to start earning serious money so that she and her husband could afford to send their kids to college.

A sweet idea: "I was substitute-teaching a study hall for seniors at the high school, and I asked them if they had any ideas for a home business. They said, 'Why don't you do cookie care packages for kids in college?' It seemed like a good idea. I called our state's small business administration—every state has one—and they said for $4 they could send me a packet on how to start a business. I brought cookies to school and tested my recipes on the students. By summer I was taking orders, and in September we started shipping."

Word of mouth: "Right away I thought, How can we get the parents to buy more than one box of cookies? How about a cookie-of-the-month club? Before long, some of them said, 'I know you've been sending cookies to my child, but can you do client gifts?'"

Kitchen aid: "I couldn't make all the cookies in my own kitchen, and I didn't want to pay for an expensive industrial mixer, so I called a local restaurant that served only lunch and dinner and asked if I could use their mixer in the mornings. They said yes. After a year, I bought a mixer—used. I'm a firm believer in saving money where you can. Now we ship about 250 dozen cookies a week."

Sugar, spice and the bottom line: "A lot of people try to turn something they love to do into a business—let's say, baking pies or dog walking. But I went at it from the opposite end: I thought, What I'd love is to run a business—what will make it work? I didn't love baking cookies—I loved being able to send my kids to college."

Short-Order Wizard

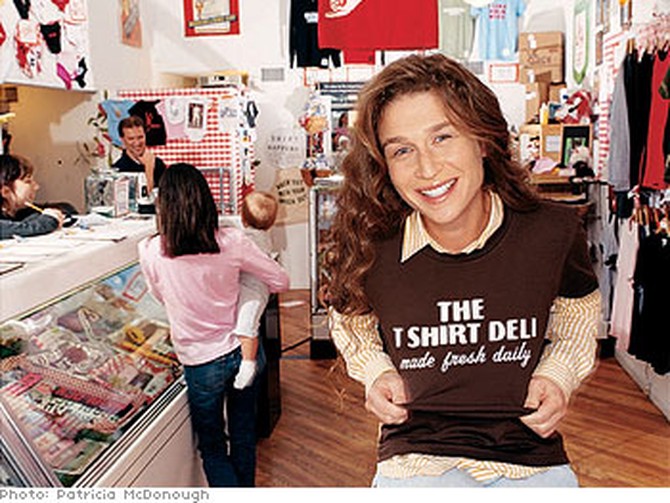

Ninel Pompushko, T-Shirt Deli

In 1999, after working in advertising for three years, writing headlines for beer campaigns and copy for TV commercials, Pompushko went freelance. Before long she began to get "beered out," but she didn't have a next step in mind. In June 2002, on a lark, she made a few dozen T-shirts with funny phrases on them and took them to a Chicago festival. They sold out.

The tees stand alone: "I started thinking how nice it would be to sell T-shirts with my funny phrases on them, but then I realized that not everybody has my sense of humor. So I thought, Why not open a T-shirt store where people can choose exactly what they want—like when you order a sandwich at a deli? It took me more than a year to open the T-Shirt Deli. I display the shirts in deli cases, we take the orders on deli checks, and you get the shirt while you wait. A basic T-shirt is $15, and everything else—letters and decals—is á la carte. When a shirt is done, we wrap it in white butcher paper and put it in a paper bag, along with a sack of potato chips."

Patent pending: "There's no store without the concept, so from the very beginning, we trademarked every single thing involved in the look of the store."

Clothes call: "I was afraid to quit freelancing, but three months after we opened, I had to—we were so busy. Now I can't believe that my business is not only paying for me but it's providing for six other people."

Unexpected bonus: "I haven't had to do any advertising—the T-shirts are their own advertisement."

Ninel Pompushko, T-Shirt Deli

In 1999, after working in advertising for three years, writing headlines for beer campaigns and copy for TV commercials, Pompushko went freelance. Before long she began to get "beered out," but she didn't have a next step in mind. In June 2002, on a lark, she made a few dozen T-shirts with funny phrases on them and took them to a Chicago festival. They sold out.

The tees stand alone: "I started thinking how nice it would be to sell T-shirts with my funny phrases on them, but then I realized that not everybody has my sense of humor. So I thought, Why not open a T-shirt store where people can choose exactly what they want—like when you order a sandwich at a deli? It took me more than a year to open the T-Shirt Deli. I display the shirts in deli cases, we take the orders on deli checks, and you get the shirt while you wait. A basic T-shirt is $15, and everything else—letters and decals—is á la carte. When a shirt is done, we wrap it in white butcher paper and put it in a paper bag, along with a sack of potato chips."

Patent pending: "There's no store without the concept, so from the very beginning, we trademarked every single thing involved in the look of the store."

Clothes call: "I was afraid to quit freelancing, but three months after we opened, I had to—we were so busy. Now I can't believe that my business is not only paying for me but it's providing for six other people."

Unexpected bonus: "I haven't had to do any advertising—the T-shirts are their own advertisement."

A Bright Bulb

Katrina Parris, Katrina Parris Flowers

After 15 years in human resources, Parris knew she wanted to do something a little more creative. In 1996 her mother died. "That was the point where I said, 'I don't want to continue in a job I don't enjoy. Life's too short.'" Parris remembered that when she was a child, her father would buy her mother an Easter lily every year, and plant the bulb in the yard where it would pop up the next spring. "I thought, wouldn't it be nice to have a flower shop in Harlem, where I live?" She decided to open one.

Growth spurt: "I couldn't quit my job, but I did take a lower-paying position that had more flexible hours. Then I signed up for night courses in flower arranging at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and at Parsons School of Design. I started taking orders out of my house. In May 2002, I quit that job and started running Katrina Parris Flowers out of our studio apartment; we launched a website, figuring since we didn't have an actual store we had to have a virtual one. In August 2003, using the money we'd saved to buy a house, we opened the shop."

Planting the seeds: "I made gift arrangements and left them at businesses in Harlem, along with my card. People called me, saying, 'I saw your flowers at the bakery.' I got our shop added to a list of approved minority suppliers that goes out to Fortune 500 companies looking to do business with minorities. We also sent out arrangements to corporations in New York with a letter of introduction, asking for a meeting. I'm very hands-on: I want to create relationships, not just projects. So each spring, I do a big complimentary delivery of a flowering bulb plant."

Katrina Parris, Katrina Parris Flowers

After 15 years in human resources, Parris knew she wanted to do something a little more creative. In 1996 her mother died. "That was the point where I said, 'I don't want to continue in a job I don't enjoy. Life's too short.'" Parris remembered that when she was a child, her father would buy her mother an Easter lily every year, and plant the bulb in the yard where it would pop up the next spring. "I thought, wouldn't it be nice to have a flower shop in Harlem, where I live?" She decided to open one.

Growth spurt: "I couldn't quit my job, but I did take a lower-paying position that had more flexible hours. Then I signed up for night courses in flower arranging at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and at Parsons School of Design. I started taking orders out of my house. In May 2002, I quit that job and started running Katrina Parris Flowers out of our studio apartment; we launched a website, figuring since we didn't have an actual store we had to have a virtual one. In August 2003, using the money we'd saved to buy a house, we opened the shop."

Planting the seeds: "I made gift arrangements and left them at businesses in Harlem, along with my card. People called me, saying, 'I saw your flowers at the bakery.' I got our shop added to a list of approved minority suppliers that goes out to Fortune 500 companies looking to do business with minorities. We also sent out arrangements to corporations in New York with a letter of introduction, asking for a meeting. I'm very hands-on: I want to create relationships, not just projects. So each spring, I do a big complimentary delivery of a flowering bulb plant."

The Givers

Donna Hilbert, Chicks with Checks

After the presidential election of 2004, the poet and writer Donna Hilbert in Long Beach, California, was dismayed. "I felt that tax cuts for the rich were not what this country needed," she says, "particularly when social programs were being starved and library budgets cut." She and some friends went to a restaurant and discussed their distress. Over dinner, they came up with a way to make a difference.

Cheap date: "We thought, what if we had a dinner at one of our houses and charged $35 per person—what you'd pay for a dinner out—and gave the money to a local children's charity, where even $1,000 would do a lot of good?"

Taste of success: "We gave our first Progressive Dinner Party the Sunday after Thanksgiving, to benefit a local center for homeless children. We served pasta salad, bread, cookies, white wine, and sparkling water. We wanted to raise $1,000—we raised $3,000! We've hosted five parties so far, one every other month. On the alternate months, we have a virtual dinner. We all stay at home and send the money we would have spent to a cause outside the community: tsunami relief, or the troubles in Sudan and Darfur."

Just desserts: "It's not only about raising money—it's raising consciousness about how much poverty exists beneath the surface of our communities. My great hope is that the word can spread, because this is something that can be done in any town."

Donna Hilbert, Chicks with Checks

After the presidential election of 2004, the poet and writer Donna Hilbert in Long Beach, California, was dismayed. "I felt that tax cuts for the rich were not what this country needed," she says, "particularly when social programs were being starved and library budgets cut." She and some friends went to a restaurant and discussed their distress. Over dinner, they came up with a way to make a difference.

Cheap date: "We thought, what if we had a dinner at one of our houses and charged $35 per person—what you'd pay for a dinner out—and gave the money to a local children's charity, where even $1,000 would do a lot of good?"

Taste of success: "We gave our first Progressive Dinner Party the Sunday after Thanksgiving, to benefit a local center for homeless children. We served pasta salad, bread, cookies, white wine, and sparkling water. We wanted to raise $1,000—we raised $3,000! We've hosted five parties so far, one every other month. On the alternate months, we have a virtual dinner. We all stay at home and send the money we would have spent to a cause outside the community: tsunami relief, or the troubles in Sudan and Darfur."

Just desserts: "It's not only about raising money—it's raising consciousness about how much poverty exists beneath the surface of our communities. My great hope is that the word can spread, because this is something that can be done in any town."

From the January 2006 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine