16 Decade-Defying Superstars Who Prove Age is Just a Number

There's no rule that says getting older means you have to feel old—just ask these

high-flying, rodeo-riding, awe-inspiring women.

Photo: Jill Greenberg

The 17-Year-Old Pilot

Kimberly Anyadike

Kimberly Anyadike

When Kimberly Anyadike was little, her heroes were superheroes. "I'd see Superman or Wonder Woman flying on TV and think, 'That's so cool!'" she says. "My brother and sister and I would tie towels around our necks for capes and run around the house jumping off the couches and banisters. Every year I would ask Santa for a jet pack." In an after-school program at Tomorrow's Aeronautical Museum in Compton, California, the 12-year-old took a spin in a single-engine Cessna 172. Midflight, she was thrilled when the instructor handed her the controls. "Afterward my mom asked if I wanted to take flying lessons, and I said, 'Yes!'"

Three years later, in 2009, Anyadike became the youngest African-American female in history to pilot a round-trip, coast-to-coast flight. (Her chaperone for all 7,000 miles was Major Levi Thornhill, one of the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, the African-American pilots whose heroism in World War II inspired Anyadike's record-setting journey.) "Flying over Texas was the most fun because there were a lot of summer rainstorms," Anyadike says. "I wasn't scared—I'm never scared. I just focus. And before every flight, I pray."

Anyadike plans to become a cardiovascular surgeon after college, but for now the big goal is earning a couple of licenses this summer—pilot's and driver's. "When I'm flying, I'm in control. I trust myself," she says. "The sound of the engine, the movement of the propeller—it's like gravity gets suspended. It's as if you're closer to heaven." Or to being a superhero. —Marcia Desanctis

Three years later, in 2009, Anyadike became the youngest African-American female in history to pilot a round-trip, coast-to-coast flight. (Her chaperone for all 7,000 miles was Major Levi Thornhill, one of the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, the African-American pilots whose heroism in World War II inspired Anyadike's record-setting journey.) "Flying over Texas was the most fun because there were a lot of summer rainstorms," Anyadike says. "I wasn't scared—I'm never scared. I just focus. And before every flight, I pray."

Anyadike plans to become a cardiovascular surgeon after college, but for now the big goal is earning a couple of licenses this summer—pilot's and driver's. "When I'm flying, I'm in control. I trust myself," she says. "The sound of the engine, the movement of the propeller—it's like gravity gets suspended. It's as if you're closer to heaven." Or to being a superhero. —Marcia Desanctis

Photo: Jill Greenberg

The 52 to 82-Year-Old Synchronized Swimmers

In Sync

In Sync

Last summer retired IBM sales rep Kathleen Richards had barely recovered from chemotherapy when she strapped on her waterproof iPod, cranked up the Abba, and plunged into the pool at her health club in Hudson, Ohio. "I couldn't wait to get back in the water," she says. Richards, 64, is part of synchronized swim team In Sync, whose members range in age from 52 to 82. "I had no hair and a skinny spaghetti body, and could hardly put one foot in front of the other, but I thought, 'I'm going to do that 'Dancing Queen' solo!'"

In Sync—which includes four grandmothers and two great-grandmothers—began as a fitness class dreamed up by 1956 national synchro champion Betty Buckles, now 75; once the students had mastered basic skills (such as "sculling," a propeller-like stroking motion), they began choreographing routines and swimming for audiences. Last January, at the dedication of a retirement community's new aquatic center, they created floating kick lines and flowerlike formations worthy of Busby Berkeley, set to the tune of "You Make Me Feel So Young."

"I think I was an otter in a past life, or maybe a dolphin," Buckles says. But even those lacking cetacean DNA can learn synchro, and In Sync is the proof. "Whenever someone says, 'I can't do this skill,' there's someone else to say, 'Last year I couldn't do it either, but just watch me now!'" —Jessica Stockton Clancy

In Sync—which includes four grandmothers and two great-grandmothers—began as a fitness class dreamed up by 1956 national synchro champion Betty Buckles, now 75; once the students had mastered basic skills (such as "sculling," a propeller-like stroking motion), they began choreographing routines and swimming for audiences. Last January, at the dedication of a retirement community's new aquatic center, they created floating kick lines and flowerlike formations worthy of Busby Berkeley, set to the tune of "You Make Me Feel So Young."

"I think I was an otter in a past life, or maybe a dolphin," Buckles says. But even those lacking cetacean DNA can learn synchro, and In Sync is the proof. "Whenever someone says, 'I can't do this skill,' there's someone else to say, 'Last year I couldn't do it either, but just watch me now!'" —Jessica Stockton Clancy

Photo: Jill Greenberg

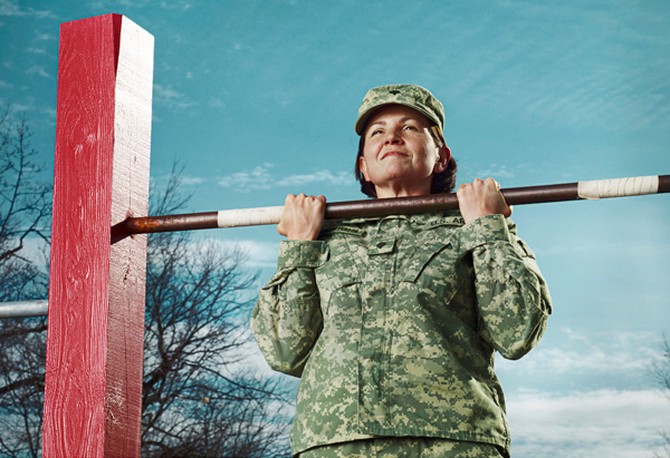

The 40-Year-Old Army Recruit

Marilee Herrera-Peterson

Marilee Herrera-Peterson

"You want to do what?" That was the general reaction when Marilee Herrera-Peterson decided to join the army. Her two daughters were divided (the 15-year-old thought she'd gone crazy; the 11-year-old thought she was the coolest mom ever), and her husband was skeptical. But Herrera-Peterson had longed to be a soldier since she was a little girl, when family members would tell mesmerizing stories about her great-uncle, a decorated veteran who served in the First and Second World Wars. Her parents, however, steered her toward college; later came marriage, children, and jobs in the restaurant and real estate industries. Then she found out that the army had raised its enlistment age to 42. And last April, on her 40th birthday, she reported for basic training. (The next-oldest female recruit at boot camp was 28.)

Since then, Herrera-Peterson has learned how to march in formation, spot an improvised explosive device, and shoot an M-16; her advanced training is in geospatial engineering (examining terrain in advance of combat operations). She's also learned that leadership comes naturally with age. "My fellow soldiers come to me to ask for advice," she says. "They're missing a boyfriend, a husband, the kids, and wondering how to deal with the situation."

Herrera-Peterson knows the feeling: She's stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, far from her family in Connecticut, and could be deployed overseas at any time. "Sometimes I think, 'Am I being selfish? Am I asking too much of my family?'" she says. "Then another voice says, 'I am finally doing what I really want to do.'" —Cynthia Ramnarace

Since then, Herrera-Peterson has learned how to march in formation, spot an improvised explosive device, and shoot an M-16; her advanced training is in geospatial engineering (examining terrain in advance of combat operations). She's also learned that leadership comes naturally with age. "My fellow soldiers come to me to ask for advice," she says. "They're missing a boyfriend, a husband, the kids, and wondering how to deal with the situation."

Herrera-Peterson knows the feeling: She's stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, far from her family in Connecticut, and could be deployed overseas at any time. "Sometimes I think, 'Am I being selfish? Am I asking too much of my family?'" she says. "Then another voice says, 'I am finally doing what I really want to do.'" —Cynthia Ramnarace

Photo: Jude Edginton

The 52-Year-Old Homemaker Turned Scientist

Patricia Alireza

Patricia Alireza

Physicist Patricia Alireza started college when she was 31 and her younger daughter was 4. "You can schedule every minute of your life," she says, "but you can never prepare for when a child gets sick or a family crisis happens. Many times I thought I would quit school." She didn't. Since completing her PhD at age 45, Alireza has published in top journals, won a research position at University College London, and in 2009 received the prestigious L'Oréal-UNESCO fellowship for promising women scientists—becoming the first and only grandmother to win this early-career award.

Born in Mexico City, Alireza moved at age 21 to California, where she met her husband; for some years they lived in his native Saudi Arabia, as he built an investing career and she raised their two girls. "We were from conservative societies, and we did what we thought was expected of us," she says. Back in California, Alireza started toward her long-deferred bachelor's degree at Occidental College while her husband took over cooking and carpooling duties. "Little by little, I went from being a housewife studying on the side to being a scientist," she says. "It wasn't easy, but when you really want something, and you're determined and dedicated, you can do it." —Darby Saxbe

Born in Mexico City, Alireza moved at age 21 to California, where she met her husband; for some years they lived in his native Saudi Arabia, as he built an investing career and she raised their two girls. "We were from conservative societies, and we did what we thought was expected of us," she says. Back in California, Alireza started toward her long-deferred bachelor's degree at Occidental College while her husband took over cooking and carpooling duties. "Little by little, I went from being a housewife studying on the side to being a scientist," she says. "It wasn't easy, but when you really want something, and you're determined and dedicated, you can do it." —Darby Saxbe

Photo: Jill Greenberg

The 23-Year-Old Mayor

Cassandra Coleman

Cassandra Coleman

Cassandra Coleman serves her constituents—literally. Twice a week, the 23-year-old mayor of Exeter, Pennsylvania, waits tables at her parents' Italian restaurant, where locals volley questions about taxes or the town budget. "I don't hesitate to give out my cell number," says Coleman, who takes calls at all hours about garbage routes and tardy snowplows. When an elderly resident needed to give her insurance company a police report following a car accident, the mayor drove to her house to deliver the paperwork. "I think of everyone as my grandma," she says, estimating that 70 percent of Exeter's 6,000 residents are over 50.

Coleman's political career began at age 3, when Exeter councilman Joseph Coyne—her grandfather—draped a sandwich board over her shoulders before she toddled off to work the polls. In 2007, after 11 years as mayor, Coyne was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor; he asked his granddaughter to finish his term. Elected to the part-time office in her own right in 2009 (current salary: $2,400 a year), Coleman has also earned a degree in political science and landed a job as Senator Bob Casey's deputy finance director; she hopes to become a congresswoman someday.

Despite all her achievements, Coleman still lives with her folks, sleeping in the bedroom she's had since age 12 (purple walls with seafoam green trim, Cabbage Patch Kids on the shelves). When her schedule gets hectic, she's been known to ask Mom to pack a sandwich or throw in some laundry for her. "When you're the mayor," she says, "living at home definitely has its privileges." —Hollace Schmidt

Coleman's political career began at age 3, when Exeter councilman Joseph Coyne—her grandfather—draped a sandwich board over her shoulders before she toddled off to work the polls. In 2007, after 11 years as mayor, Coyne was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor; he asked his granddaughter to finish his term. Elected to the part-time office in her own right in 2009 (current salary: $2,400 a year), Coleman has also earned a degree in political science and landed a job as Senator Bob Casey's deputy finance director; she hopes to become a congresswoman someday.

Despite all her achievements, Coleman still lives with her folks, sleeping in the bedroom she's had since age 12 (purple walls with seafoam green trim, Cabbage Patch Kids on the shelves). When her schedule gets hectic, she's been known to ask Mom to pack a sandwich or throw in some laundry for her. "When you're the mayor," she says, "living at home definitely has its privileges." —Hollace Schmidt

Photo: Jill Greenberg

The 64-Year-Old Rodeo Rider

Bettie Cox

Bettie Cox

Bettie Cox's long brown hair flies loose when she and her tawny horse, Merry, compete in the high-speed barrel race, zipping around a series of metal drums in a cloverleaf pattern. Their record is 18.973 seconds—not fast enough to reach the winner's circle, but Cox doesn't need a prize to feel victorious. "I don't think there's anybody as old as me with her butt on a horse's back," says the 64-year-old member of the Hawaii Women's Rodeo Association. "Riding is what keeps me 15."

Growing up, Cox spent many mornings galloping around the 100 acres her family owned in Virginia. But when she was 18, her parents divorced, her beloved horses were sold, and the land was absorbed into Washington Dulles airport. After marrying at 21, she settled down in Florida and later Hawaii for a quiet life as a mom and homemaker. Then one day in 2001, Cox was visiting a neighbor's ranch when a shy month-old filly rubbed up against her: "She wouldn't leave me alone. And when I found out she was born on my birthday, I decided on the spot to buy her and her brother." A month later Cox added Merry to the family ("the fastest feet I've ever seen"). Her husband built a stable for the equine trio on their acre of Oahu land, and Cox started rodeo lessons to keep herself and her horses in shape.

"It's taken ten years to get strong enough to do the things I do today," she says. "I ride, ride, ride, and when I'm not riding I'm picking up manure, pulling up weeds. I'm not out there to win anything. I'm there to have a great time with my horse, to improve my balance, my muscles, my health. When you're older, you'd best not be wasting your time. I'm not! I'm having fun." —Cynthia Ramnarace

Growing up, Cox spent many mornings galloping around the 100 acres her family owned in Virginia. But when she was 18, her parents divorced, her beloved horses were sold, and the land was absorbed into Washington Dulles airport. After marrying at 21, she settled down in Florida and later Hawaii for a quiet life as a mom and homemaker. Then one day in 2001, Cox was visiting a neighbor's ranch when a shy month-old filly rubbed up against her: "She wouldn't leave me alone. And when I found out she was born on my birthday, I decided on the spot to buy her and her brother." A month later Cox added Merry to the family ("the fastest feet I've ever seen"). Her husband built a stable for the equine trio on their acre of Oahu land, and Cox started rodeo lessons to keep herself and her horses in shape.

"It's taken ten years to get strong enough to do the things I do today," she says. "I ride, ride, ride, and when I'm not riding I'm picking up manure, pulling up weeds. I'm not out there to win anything. I'm there to have a great time with my horse, to improve my balance, my muscles, my health. When you're older, you'd best not be wasting your time. I'm not! I'm having fun." —Cynthia Ramnarace

From the May 2011 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine