This Writer's Aha! Moment After Clearing Out Her Late Mother's House

Short shorts, ratty posters, iffy eggnog: Suzanne Rico never saw her mother pass up a deal—and now she knows why.

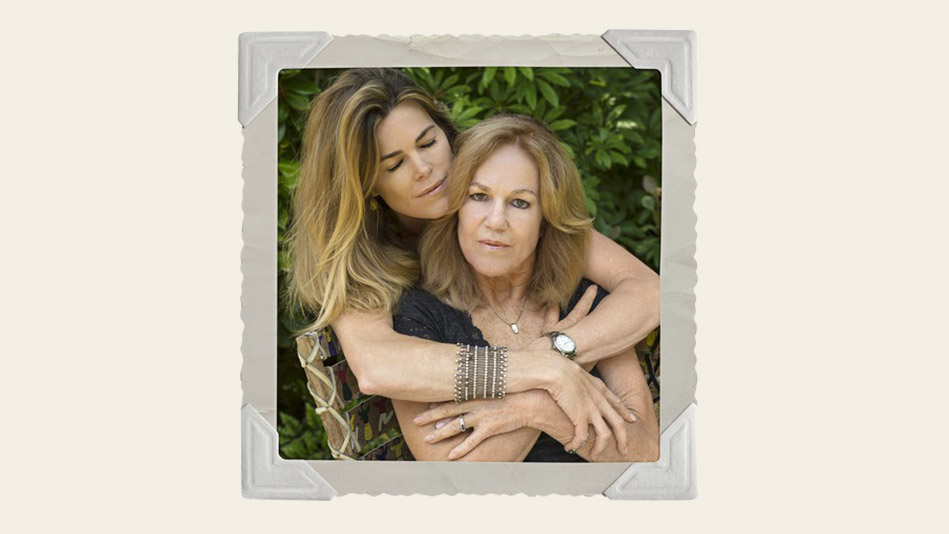

Courtesy of Suzanne Rico

Early birds were already crowding the driveway of the Los Angeles estate when I approached with my mother, her gait tilted by the feeding tube in her side. Spread on tables were objects left behind by the house's late owners, Bob Hope and his wife, Dolores: boater hats, a dart board, kitchen utensils. Here was Bob on a magazine cover, golf club in hand, a monkey as his caddy. Here was a plastic statue of Bob in fatigues, one finger missing from his salute. He'd been dead for nine years, Dolores for one. But Hollywood legends didn't interest my mother. What mattered were bargains.

She was born in Germany, two years before World War II began. Her mother was killed when a bomb struck their Bavarian farmhouse; her father was forced to send his children to an orphanage while he looked for work. "I didn't even have a toothbrush!" Mom would say when, as a kid, I balked at brushing. She was 11 when she crossed the Atlantic and first saw America—a dream for the taking if, she came to believe, one could stretch a dollar.

During my childhood, waste—of shampoo, paper towels, a squashed tuna sandwich in my sack lunch—was a crime. My sisters and I understood the concept of frugality but were baffled by our mother's definition of a "deal." She'd buy cartons of eggnog after Christmas—10 cents each since they were about to spoil—and cram them into our freezer; we'd drink them until Easter.

Now, at the Hopes', a snow globe glinted in the November sun, the flakes the same color as my mother's post-chemo hair. She picked up a 1950s-era colander—only a buck!—and ran her fingers over its metal rim.

Linda Hope, Bob and Dolores's first child, manned the nearest till. I wanted to speak to her. I wanted her to bestow some wisdom about the road of loss she had just traveled with her mother—the road I was now on.

"This must be weird," I said. Linda nodded as strangers rifled through her history. "But," she said, "life moves on." She rang up a woman clutching a turkey-shaped candle.

Linda's words pressed hard against my heart. How could she let it all go so easily? When my mother was gone, I told myself, I'd make a shrine of her things. I'd love my mother better than Linda had loved hers. I searched the crowd for my mom and found her near the white-brick house, behind which lay the lawn where Nixon's helicopter had once landed for a golf date. Mom looked like a stick figure in the yoga pants we'd bought in Target's children's section. She held a poster of the horses of San Marcos. "Cropped and framed," she said, beaming.

Soon after, a plunging blood count landed her in the hospital. A month later, I bought a dress at an outlet mall for her funeral: Calvin Klein, $19.99.

Photo: Richard Ressman

Photo: Richard Ressman

Afterward, my sisters and I sat on our mother's bed, sorting her possessions. A colorful pile of short shorts—Mom's Daisy Dukes, we joked—sat on a shelf, tags attached. COMPARE AT $29.99. CLEARANCE PRICE, $2.99. "What the hell was she doing with all this junk?" I asked. Eager to banish any reminder of the battle we'd just lost, I donated nearly everything.

Days later, this scattering of my mother's stuff began to sting. I understood now: The thrill of finding a diamond in T.J. Maxx's rough had helped remedy the desolation of her childhood. My mother had decided she would never again have nothing. The stuff had been a stockpile against loss.

One spring morning, I dug out my mother's denim short shorts and tried them on. They fit perfectly. Wearing them conjures the mom who climbed a ladder to trim her orange trees. She's up there in the California sun, her legs summer brown. The Hopes' colander is with me, too. When I use it to rinse bitter arugula and sweet strawberries, I no longer judge Linda for letting it go.

Suzanne Rico is a Los Angeles-based journalist. She is currently working on a memoir.

She was born in Germany, two years before World War II began. Her mother was killed when a bomb struck their Bavarian farmhouse; her father was forced to send his children to an orphanage while he looked for work. "I didn't even have a toothbrush!" Mom would say when, as a kid, I balked at brushing. She was 11 when she crossed the Atlantic and first saw America—a dream for the taking if, she came to believe, one could stretch a dollar.

During my childhood, waste—of shampoo, paper towels, a squashed tuna sandwich in my sack lunch—was a crime. My sisters and I understood the concept of frugality but were baffled by our mother's definition of a "deal." She'd buy cartons of eggnog after Christmas—10 cents each since they were about to spoil—and cram them into our freezer; we'd drink them until Easter.

Now, at the Hopes', a snow globe glinted in the November sun, the flakes the same color as my mother's post-chemo hair. She picked up a 1950s-era colander—only a buck!—and ran her fingers over its metal rim.

Linda Hope, Bob and Dolores's first child, manned the nearest till. I wanted to speak to her. I wanted her to bestow some wisdom about the road of loss she had just traveled with her mother—the road I was now on.

"This must be weird," I said. Linda nodded as strangers rifled through her history. "But," she said, "life moves on." She rang up a woman clutching a turkey-shaped candle.

Linda's words pressed hard against my heart. How could she let it all go so easily? When my mother was gone, I told myself, I'd make a shrine of her things. I'd love my mother better than Linda had loved hers. I searched the crowd for my mom and found her near the white-brick house, behind which lay the lawn where Nixon's helicopter had once landed for a golf date. Mom looked like a stick figure in the yoga pants we'd bought in Target's children's section. She held a poster of the horses of San Marcos. "Cropped and framed," she said, beaming.

Soon after, a plunging blood count landed her in the hospital. A month later, I bought a dress at an outlet mall for her funeral: Calvin Klein, $19.99.

Photo: Richard Ressman

Photo: Richard Ressman

Afterward, my sisters and I sat on our mother's bed, sorting her possessions. A colorful pile of short shorts—Mom's Daisy Dukes, we joked—sat on a shelf, tags attached. COMPARE AT $29.99. CLEARANCE PRICE, $2.99. "What the hell was she doing with all this junk?" I asked. Eager to banish any reminder of the battle we'd just lost, I donated nearly everything.

Days later, this scattering of my mother's stuff began to sting. I understood now: The thrill of finding a diamond in T.J. Maxx's rough had helped remedy the desolation of her childhood. My mother had decided she would never again have nothing. The stuff had been a stockpile against loss.

One spring morning, I dug out my mother's denim short shorts and tried them on. They fit perfectly. Wearing them conjures the mom who climbed a ladder to trim her orange trees. She's up there in the California sun, her legs summer brown. The Hopes' colander is with me, too. When I use it to rinse bitter arugula and sweet strawberries, I no longer judge Linda for letting it go.

Suzanne Rico is a Los Angeles-based journalist. She is currently working on a memoir.