How to Raise a Carefree Kid, Even If You're Terrified

The author of Kickflip Boys explains his struggle with fear and self-control after his 6-year-old son's accident.

Photo: Tang Yau Hoong/Getty Images

I was in our backyard, flipping burgers, Dick Dale twanging through kitchen windows, when every parent's nightmare arrived, all crunching metal and screeching tires. A red ball had rolled into the street. Sean, age 6, the older of my two boys, who'd been playing out front with his brother and three friends, volunteered to fetch it.

He got midway across the street and picked up the ball as a Toyota Corolla sped toward him, doing 30 (the cops later estimated) in a 15-mile-an-hour "Slow Children Playing" zone.

Sean told us later that he thought the driver saw him, assumed she'd stop. When she didn't—because she was texting, we'd later learn—Sean tried to jump. His feet barely left the ground when the Corolla caught him midthigh, bounced him off its hood and sent him cartwheeling through the air as his brother and friends watched.

I followed the sound of screams and howls to find Sean in an awful heap in a neighbor's yard, his left leg smashed and wrong, his shoeless left foot bent impossibly up to his left ear, pants wrenched low. He was unconscious, covered in grass and dirt, and for the worst moments of my life, I screamed and clawed at the ground, certain my boy was dead.

During the awful wait for the EMTs, Sean's eyes fluttered open and a piece of me died at the exact moment my kid awoke and lived.

At the hospital, with Sean stabilized and IV'd, his leg in traction, my rattled wife, Mary (who'd been at work when the accident happened), at his bedside, I locked myself in a too-bright bathroom and fell to the floor, sobbing.

Six months later, after removing the pins from Sean's femur, pins that I kept in a lockbox like sacred objects, the doctor told us our kid was healed and to "just let him be a boy again." I don't think I ever healed, though. I had failed: my sons, my wife, failed us all. That day would follow us like a ghost dog. We referred to it as "Sean's accident," or just "the accident."

Although I had experienced, just for a moment, the loss of a child, I tried to scold and coach myself. You got him back! He didn't die! Every day is a gift! Why aren't you happy? Partly the answer was this: I knew it could happen again, in a snap. He wasn't charmed; he was vulnerable. So was his brother, Leo. The world was full of danger, of speeding and texting drivers. The possibility of further doom taunted me.

Especially when both of my sons became skateboarders. Their hobby was innocent enough at first. They skated slowly down our driveway, then at skate parks and summer skate camps, always sheathed in the protection of a helmet and pads. But after we moved to Seattle and the boys began middle school, their hobby became a passion and then an obsession, and it moved from skate parks to the streets, and the helmets and pads were left behind.

Mary and I had encouraged their skating after they'd bailed on soccer and baseball. It wasn't clear until later what we had endorsed: a sport and a culture built on the tenets of freedom and rebellion. Street skating became their preferred format, which meant their playing field was essentially a return to the scene of the crime of Sean's accident.

With their bus passes, they traversed the city, looking for curbs and ledges, off-limits spots that carried a whiff of danger. I'd spy on their YouTube channel, a daddy voyeur. I took calls from security guards, and eventually the police, when they got caught trespassing.

My wife and I handled this in our own ways. Mine was always tainted by the image of Sean in a heap on that lawn. Hers was leavened by hope that they were fully exploring their passion, that honing their sense of risk and reward, of danger and safety—rather than having it foisted on them by helicoptering parents—would develop street smarts and independence. But we weren't always in sync. While I fretted, my wife trusted.

We had so many conversations over the years about whether we were being overprotective (because of the accident) or underprotective (because of the accident). But we seemed incapable of keeping them from flying—heads first—toward increasingly treacherous skate tricks.

We once watched a YouTube video of Sean doing a trick at the indoor skate park called Innerspace, losing his footing while trying to kickflip onto a box called a mani-pad, and then cracking his forehead against the metal rim. He was bruised, but not badly injured.

We once watched Leo, the riskier one, fly off an eight-stair descent without a helmet. I thought: "Is this it? Is it Leo's turn now? Will I fail him too?" Leo often assured me that he'd never been injured skating, and never would, because: "You learn how to fall."

Sean's attitude throughout was encapsulated by the comment, after getting punished for some skate-related infraction: "Why did God give us lives? To have fun. I'm just having fun!"

Sean would return to the ER twice more. Once after a sidewalk wipeout and a jammed shoulder (no breaks). Once after he was beaten with his own skateboard by a drunk at a beach party. He was battered and bruised, but no breaks or concussion. A social worker came and asked to speak with Sean alone, and I knew what she would ask him ("Son, did your father hurt you?"), and I felt guilt and shame even if I'd done nothing wrong. Or had I?

Mary worried less than I. Partly because she was optimistic and hopeful, and partly (or so I told myself) because she wasn't there that day, hadn't seen our crumpled boy, didn't carry that image with her like a faded Polaroid.

At times, I've tried to find a positive spin. I had seen a scary thing, but it made me stronger. Didn't it? Just like the premature deaths of my sister and my mother gave me some sort of inner strength. Or did I have it all wrong? Was nursing and nurturing the worst memory of my life like picking at a scab, preventing it from healing? A therapist might've told me something like that, if I'd had the good sense to visit one.

"They're fine," my wife/therapist once told me. "You can't worry so much. We have to be patient. They're going to be fine."

I found therapy elsewhere—paddleboarding, skiing, yoga, bourbon—and sometimes a yoga instructor's words helped. Be here now. Judge not. Trust in the universe. Other times, lying there in corpse pose, I'd try to swat away the memory of Sean, gouged into that lawn, and I'd force myself to think of who he really was: nearly 6 feet tall now, skinny and pimply and handsome, still skating, not a victim or an injured boy but a young man.

I've learned this much: We can't keep our kids safe. Not really. And we can't raise them inside a protective bubble. Not without backlash and consequences. We need to accept them, trust them, be happy with the moments we've got, keep them grounded but not fenced in, let them know they're loved, and not alone. My boys are happy and free; they're not afraid. I wish I could say the same about me. I'll always remember. I don't think the ache will ever leave.

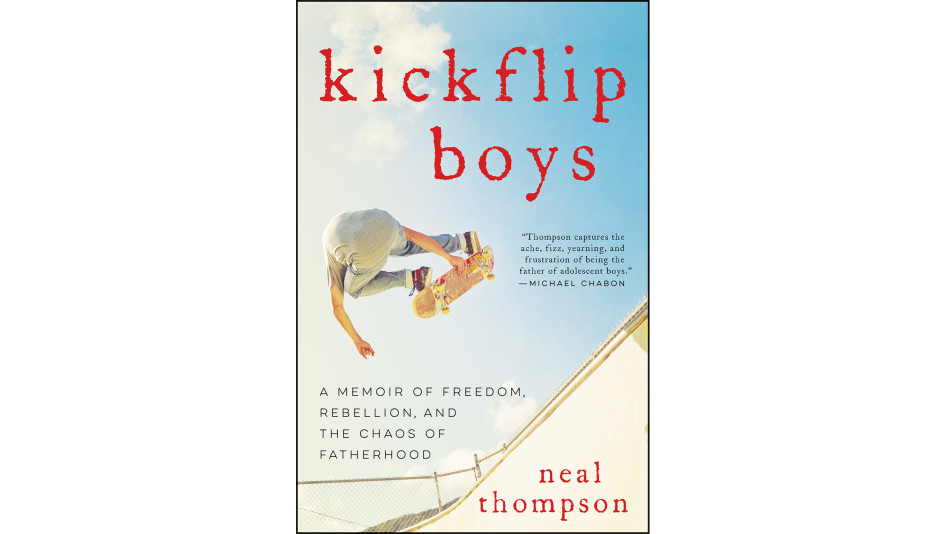

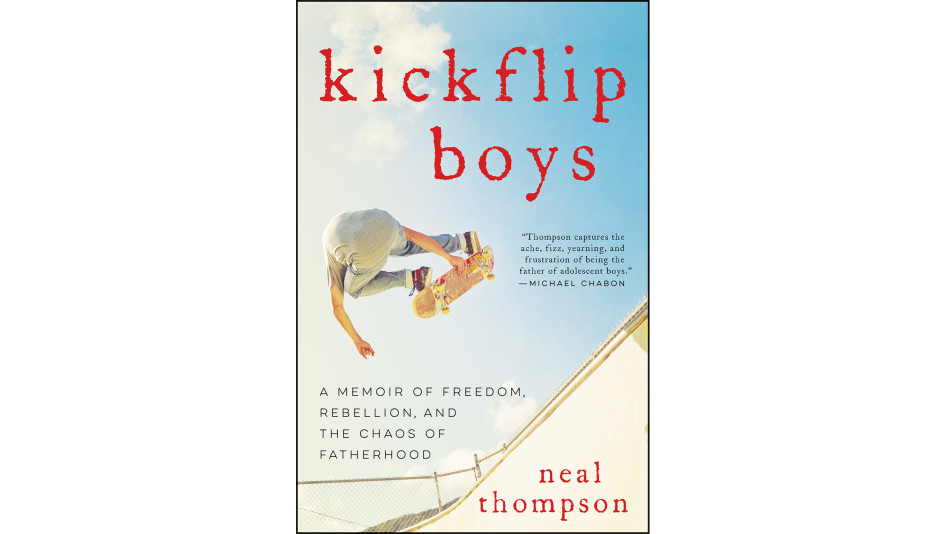

Neal Thompson is the author of the new memoir Kickflip Boys, the biography A Curious Man and three other books.

He got midway across the street and picked up the ball as a Toyota Corolla sped toward him, doing 30 (the cops later estimated) in a 15-mile-an-hour "Slow Children Playing" zone.

Sean told us later that he thought the driver saw him, assumed she'd stop. When she didn't—because she was texting, we'd later learn—Sean tried to jump. His feet barely left the ground when the Corolla caught him midthigh, bounced him off its hood and sent him cartwheeling through the air as his brother and friends watched.

I followed the sound of screams and howls to find Sean in an awful heap in a neighbor's yard, his left leg smashed and wrong, his shoeless left foot bent impossibly up to his left ear, pants wrenched low. He was unconscious, covered in grass and dirt, and for the worst moments of my life, I screamed and clawed at the ground, certain my boy was dead.

During the awful wait for the EMTs, Sean's eyes fluttered open and a piece of me died at the exact moment my kid awoke and lived.

At the hospital, with Sean stabilized and IV'd, his leg in traction, my rattled wife, Mary (who'd been at work when the accident happened), at his bedside, I locked myself in a too-bright bathroom and fell to the floor, sobbing.

Six months later, after removing the pins from Sean's femur, pins that I kept in a lockbox like sacred objects, the doctor told us our kid was healed and to "just let him be a boy again." I don't think I ever healed, though. I had failed: my sons, my wife, failed us all. That day would follow us like a ghost dog. We referred to it as "Sean's accident," or just "the accident."

Although I had experienced, just for a moment, the loss of a child, I tried to scold and coach myself. You got him back! He didn't die! Every day is a gift! Why aren't you happy? Partly the answer was this: I knew it could happen again, in a snap. He wasn't charmed; he was vulnerable. So was his brother, Leo. The world was full of danger, of speeding and texting drivers. The possibility of further doom taunted me.

Especially when both of my sons became skateboarders. Their hobby was innocent enough at first. They skated slowly down our driveway, then at skate parks and summer skate camps, always sheathed in the protection of a helmet and pads. But after we moved to Seattle and the boys began middle school, their hobby became a passion and then an obsession, and it moved from skate parks to the streets, and the helmets and pads were left behind.

Mary and I had encouraged their skating after they'd bailed on soccer and baseball. It wasn't clear until later what we had endorsed: a sport and a culture built on the tenets of freedom and rebellion. Street skating became their preferred format, which meant their playing field was essentially a return to the scene of the crime of Sean's accident.

With their bus passes, they traversed the city, looking for curbs and ledges, off-limits spots that carried a whiff of danger. I'd spy on their YouTube channel, a daddy voyeur. I took calls from security guards, and eventually the police, when they got caught trespassing.

My wife and I handled this in our own ways. Mine was always tainted by the image of Sean in a heap on that lawn. Hers was leavened by hope that they were fully exploring their passion, that honing their sense of risk and reward, of danger and safety—rather than having it foisted on them by helicoptering parents—would develop street smarts and independence. But we weren't always in sync. While I fretted, my wife trusted.

We had so many conversations over the years about whether we were being overprotective (because of the accident) or underprotective (because of the accident). But we seemed incapable of keeping them from flying—heads first—toward increasingly treacherous skate tricks.

We once watched a YouTube video of Sean doing a trick at the indoor skate park called Innerspace, losing his footing while trying to kickflip onto a box called a mani-pad, and then cracking his forehead against the metal rim. He was bruised, but not badly injured.

We once watched Leo, the riskier one, fly off an eight-stair descent without a helmet. I thought: "Is this it? Is it Leo's turn now? Will I fail him too?" Leo often assured me that he'd never been injured skating, and never would, because: "You learn how to fall."

Sean's attitude throughout was encapsulated by the comment, after getting punished for some skate-related infraction: "Why did God give us lives? To have fun. I'm just having fun!"

Sean would return to the ER twice more. Once after a sidewalk wipeout and a jammed shoulder (no breaks). Once after he was beaten with his own skateboard by a drunk at a beach party. He was battered and bruised, but no breaks or concussion. A social worker came and asked to speak with Sean alone, and I knew what she would ask him ("Son, did your father hurt you?"), and I felt guilt and shame even if I'd done nothing wrong. Or had I?

Mary worried less than I. Partly because she was optimistic and hopeful, and partly (or so I told myself) because she wasn't there that day, hadn't seen our crumpled boy, didn't carry that image with her like a faded Polaroid.

At times, I've tried to find a positive spin. I had seen a scary thing, but it made me stronger. Didn't it? Just like the premature deaths of my sister and my mother gave me some sort of inner strength. Or did I have it all wrong? Was nursing and nurturing the worst memory of my life like picking at a scab, preventing it from healing? A therapist might've told me something like that, if I'd had the good sense to visit one.

"They're fine," my wife/therapist once told me. "You can't worry so much. We have to be patient. They're going to be fine."

I found therapy elsewhere—paddleboarding, skiing, yoga, bourbon—and sometimes a yoga instructor's words helped. Be here now. Judge not. Trust in the universe. Other times, lying there in corpse pose, I'd try to swat away the memory of Sean, gouged into that lawn, and I'd force myself to think of who he really was: nearly 6 feet tall now, skinny and pimply and handsome, still skating, not a victim or an injured boy but a young man.

I've learned this much: We can't keep our kids safe. Not really. And we can't raise them inside a protective bubble. Not without backlash and consequences. We need to accept them, trust them, be happy with the moments we've got, keep them grounded but not fenced in, let them know they're loved, and not alone. My boys are happy and free; they're not afraid. I wish I could say the same about me. I'll always remember. I don't think the ache will ever leave.

Neal Thompson is the author of the new memoir Kickflip Boys, the biography A Curious Man and three other books.