The Fateful Discovery a Woman Made After the Sudden Death Of Her Infant Child

After the sudden loss of her infant son, Rebecca Gummere made a discovery that upended everything she knew about life, death, faith—and the thread that connects us all.

Illustrations: Vivienne Flesher

In human gestation, the precursor of the heart, called the heart tube, forms in a region known as the cardiogenic field. On or around the 23rd day, tracing the path of some invisible template, the multiplying cells begin a right-looping arc, developing in the form of a spiral, as would a rose, or a seashell, or a galaxy.

More than 40 years ago, Spanish cardiologist Francisco Torrent-Guasp, using his gloved fingers, separated the tissue of a bovine heart at the naturally occurring juncture where the ventricular myocardial band circles around to meet itself. He unfurled the organ, spreading it out flat, a reminder that while for centuries science has continued to treat the heart as a four-chambered construct, there is an added dimension. The heart is also an elegant Gordian knot of one continuous muscle that with each beat contracts and relaxes, pumping blood out and allowing it back in. In the course of one day the adult heart will beat more than 86,000 times, in one year more than 31 million times. By age 70, a human heart will have logged upwards of 2.3 billion contractions, taking cues from the electrical impulses that move through it like lightning up a staircase.

Even the heart of a baby who lives just 42 days will pulsate more than 6 million times before its final, fluttering beat.

“Are you ready?” asks the pathologist.

I nod, making a chalice of my hands, and he reaches down into the plastic bucket and lifts my son’s heart and lungs out of the water. I feel a slight weight, as if I am holding a kitten or a bird.

I blink and the world turns sideways beneath me.

Cooper was born on a Sunday morning in October 1982. In every way, his arrival was ordinary. He was delivered after eight hours of labor; following his first breath, he let out a sharp, lusty cry, his body turning a healthy pink as oxygen moved through his bloodstream. He scored high marks on the standard Apgar newborn assessment. The pediatrician observed that his six-and- a-half-pound birth weight contrasted with that of our first child, Liam, born weighing nearly nine pounds, but she did not appear concerned and made no further comment.

That evening a report came on about a tropical storm that had hit the coast of Central America. Watching the grainy footage of tearing waves and flailing trees, I felt a wrenching, not of physical origin but something deeper, more terrifying, so that my breath came in short bursts. I turned off the television and pushed away the dinner tray. I was being silly, I told myself. Hormones and exhaustion, I thought.

That night Cooper fell asleep partway through his feeding, his mouth working the air for a brief moment before he sank into the crook of my arm. The nurse said some babies need encouragement and suggested I uncover his feet.

On the second day, after his circumcision, Cooper stayed in my room and nursed a little and slept, nursed and slept again. The nurse said he was probably worn out from the procedure.

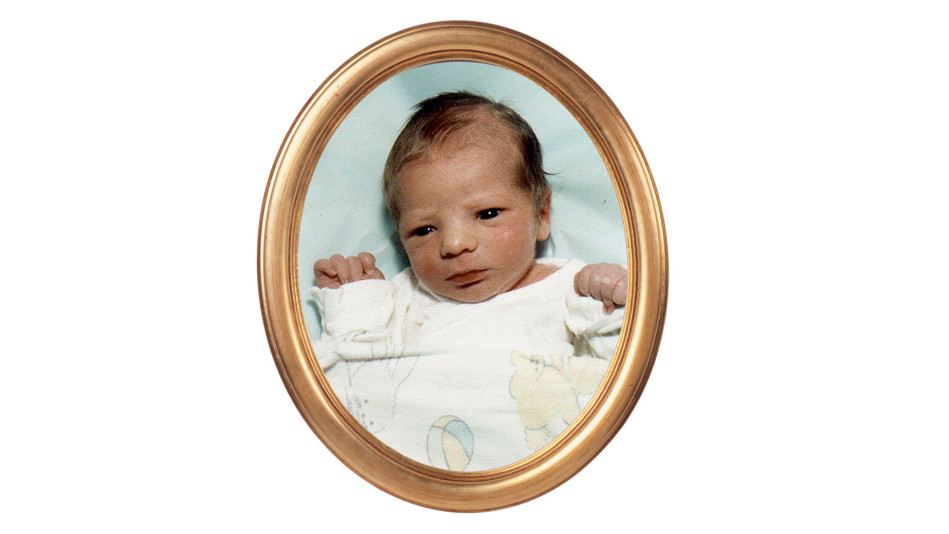

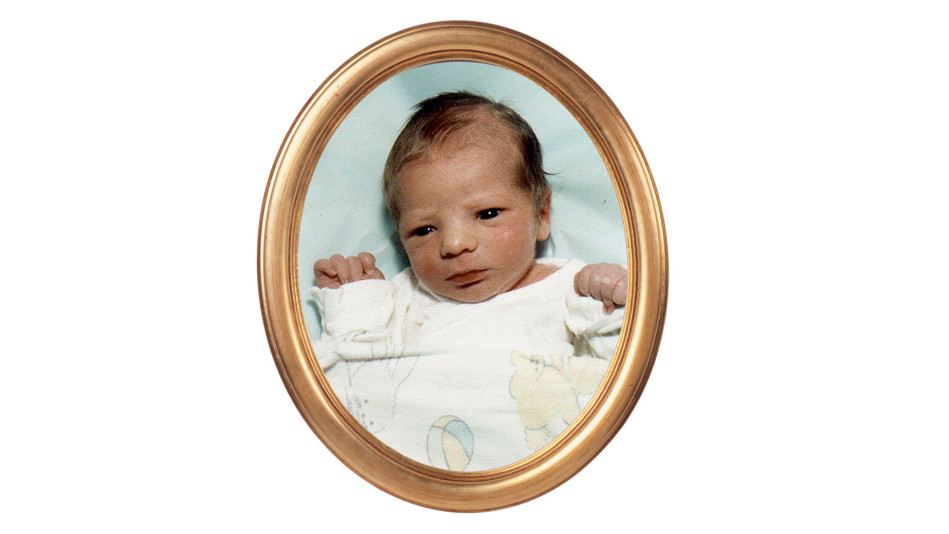

Cooper, the day after his birth, October 25, 1982.

On the morning of the third day, as we packed to go home, our pediatrician stopped by to say she was “hearing a little heart murmur.” She suggested we take Cooper to the children’s hospital to see her friend, a pediatric cardiologist. She said murmurs are common, that nearly half of all newborns have them. She did not seem overly concerned. “Just to give a listen,” she said, signing the discharge papers.

The cardiologist, a trim man who looked to be in his early 40s, met us in the hospital lobby. We followed him into the elevator and up two floors to his office, where he performed a brief examination, narrowing his eyes as he listened to our son’s heart. Then he draped the stethoscope around his neck and with a quick smile told us he’d like to get some X-rays.

We followed him down a hall and into a room where two technicians were waiting. One took Cooper and held him while I removed his clothing, leaving him in his diaper. She placed him on a small saddle with his arms above his head while a hard plastic case was fastened around his torso, holding him there like the tiny victim of a stickup. He wailed furiously. We watched from a window in the next room as the X-ray machine swiveled around him, capturing images from numerous angles.

After the X-rays, he was taken for an ultrasound. This time my husband and I sat holding hands in the waiting area. It’s probably nothing, we assured each other. They’re just being cautious, we agreed.

When at last we sat in the cardiologist’s office, he placed a chair across from us so that his knees almost touched ours. He held a notepad in one hand, a pen in the other. We moved forward to see what he was drawing, to listen as he deciphered the blue scrawls filling the empty page.

“Do you know what a heart looks like?” he asked, and I remember having one distinct thought: We should run.

Outside in the bright October day, traffic hummed along as if everything were normal, as if I were not holding a baby whose blood pressure was at once too high and too low, blood backed up in some vessels like a clogged river, slowing to a trickle in others, whose aorta narrowed to the width of a sewing thread just below the heart, whose lungs were compressed by his enlarged right atrium and ventricle.

Early the next morning, we returned to hand him over again, this time to a lion of a man with massive hands and a mane of graying reddish hair, a pediatric heart surgeon who—while we paced like animals in a crowded waiting room awash in the smells of French fries and cigarette smoke and body odor—would make a long, delicate incision in our son’s small torso, beginning just under the sternum and traversing the left side of his body around to the back, removing the scalpel just under the left shoulder blade. He would pull back the flesh and uncover the mistake, cut out the narrowed section and resect the aorta so blood would flow unimpeded and pressure would stabilize, and the small heart that had been working so hard could ease into a sure and steady rhythm.

Six hours later, the surgeon came to find us. “Everything went fine,” he said. I wept into his broad chest.

In the NICU—the neonatal intensive care unit—there was neither night nor day but another kind of time altogether. In a far corner of that too-bright room was a plastic bassinet, and inside lay Cooper, his eyes wide with shock and pain.

Four days later, my husband and I were able to hold him. The next day I was able to nurse him. When we brought him home on the tenth day, he had already gained a pound, and once he was in a regular feeding routine, he was able to sleep. His cheeks grew round, and he kicked his legs in excitement.

I let myself breathe.

On an overcast morning in early December, Cooper, now 6 weeks old, wakened fretful and vomited after his morning feeding. My husband was away on a business trip, so I dropped off Liam at a friend’s and took Cooper to our pediatrician. She gave him a thorough examination, listening intently to his heart, his lungs, his pulse points—all, she said, sounding normal. She thought he had likely picked up a virus and prescribed electrolyte fluids and rest.

Back home he continued to fuss, ate little, and toward evening had a short bout of diarrhea. After Liam was in bed, I called my husband, who was preparing to board his overnight return flight. We chatted about his predawn arrival and the trip he’d been on—anything to avoid naming our fear. Then I sat in the quiet house and listened to the ticking mantel clock and rocked Cooper, and after a time he quieted and was able to take a little fluid, and we both dozed in the chair.

Then this: He wakes, fussing, squirming. I change his diaper and notice he is cool, so cool to the touch, and his skin has gone white, his surgical scar now a harsh purple line against his pale torso.

And then: I am on the phone with the pediatrician, hating to bother her because it is nearly 11 at night, hating to be so inept, but I tell her about this new thing, this coolness, and she says, “Try putting him in a warm bath and see if that doesn’t help.”

So I do. And it calms us both, but now I cry, too, afraid and very tired, and I talk to him between my fits of weeping, saying, “There. Isn’t that nice? Doesn’t that feel good? Aren’t you better?” He lies in the tub without kicking or moving, looking up at me. I listen to his quiet breathing and watch his dark eyes watching me.

I dry him off and dress him in a pine green fleece romper and tuck him inside a cotton flannel receiving blanket and then wrap a crocheted afghan around him. I bring him downstairs and rock him some more. Now he sleeps, but I am unsettled. His face feels so cool. I call the pediatrician again.

“Okay,” she says, “let’s put him back in the hospital till he gets over this,” and tells me she will meet us there.

I call my neighbor Jerry to come take Liam to their house. I call my sister-in-law to come with me to the hospital. I put Cooper on the sofa. I notice his lungs sound congested, and this is concerning, this rattling sound is new, but he is resting at last, so I lay him next to a cushion and run upstairs to pull Liam from his bed, and he is sleeping so hard, he cannot wake up. His legs buckle; he’s just 2 years old, but I struggle to hold up his dead weight as I try to dress him. I carry him downstairs, where I place him on the shag carpet and slide his arms into his winter jacket, stuff his limp feet into his boots, pull his hat onto his head. He sleeps through it all.

My neighbor arrives. I am saying things like “the baby” and “my sister-in-law” and “the hospital.” Everything is whirling.

And then in an instant I feel a terrible pulling inside me. I let Liam slide to the floor and look across the room at Cooper.

“He is not breathing,” I say, and I know it is true.

“What?” Jerry is confused.

“He’s not breathing.” I run to the sofa, peel away the layers, unzip the fleece, draw up his undershirt. Lay my ear to his cool chest. All I hear is the thud of my own heart. I take a deep breath, lift my head, place it on his chest again.

“Call 911,” I shout, and then everything is changed.

I hold him, panicked, try to breathe into his mouth, try to push on his small chest, but I don’t know what I’m doing, so instead I rock him and I whisper because I have no voice. “Please, God, not my baby, not my baby. Please don’t take my baby.”

The door bangs open. For a moment there is confusion. At first the EMTs go to Liam, asleep on the floor, thinking he is the one in distress.

I cannot speak, hunched over Cooper, trying to breathe for both of us.

“Over here,” yells Jerry.

They take Cooper from me, put him on the dining room table, a table I will later have to give away. They listen and look and listen some more, for a long time, with grim faces.

At last one of the paramedics pronounces what we all know: “This baby is deceased.”

A sob escapes from one of the squad members, a young dark-haired man, and he wipes his eyes. “I’m so sorry,” he says.

My husband arrives home sometime before 4 in the morning. I meet him at the door. He sees my face and behind me our pastor and the pediatrician and friends and neighbors, and he shakes his head, saying no, and refusing to come inside, putting his hand out and saying no, no, and no. Then his legs give way and he falls to his knees. We kneel together on our front porch, first light creeping from the east.

When the coroner arrives, my husband and I hold our baby and stroke the blanket covering his small, cold body. We kiss his forehead and tell him we love him, and we hand him over one last time.

Since he has died at home, an autopsy is mandatory. We are devastated to think of him being cut open again, but we have no say in the matter, and we sign the papers, allowing the hospital to do what it must.

Liam sits next to me on the sofa and asks again where the baby has gone, and I tell him again that the baby was very sick, and it was a kind of sick that couldn’t get better, but it’s not a kind of sick you can catch, you are fine. But the baby was sick and the baby died and now he is in heaven with God. I tell Liam God is taking good care of our baby, but I am not sure I believe it, not sure at all.

I want God to be real. I need there to be Someone in charge, and I need there to be a heaven, some place where I know my baby is safe and cared for and loved. I think back to when I was a child, moments when I sensed a presence—at 8, seated between my mother and sister in a church pew, the sun painting my leg in reds and golds and blues, believing God was somehow in that dance of color; at 12, perched on a hillside as a wild wind stirred then quieted in the field behind me, and then in the utter stillness came the piercing call of one lone bird, sending chills over my skin, the very voice of God in my ear.

Where are You now? I wonder. Friends from a Bible study I’ve recently joined come to sit with me, read psalms, offer prayers against the descending darkness. Where are You now?

Sometimes, late in the afternoon when Liam is napping and the house is quiet, I hear a baby’s cries coming as if from some distant room. I startle each time before I remember what my doctor has told me, that these are “phantom cries,” common with women who have lost a child.

In time the phantom crying ceases. I clean Cooper’s room and box up his clothing, keeping his cotton hospital blanket and a small stuffed bear, and some days I sit in the rocker and hold them close to me.

Six months later, I am pregnant again. My husband and I are terrified at the thought of another loss, and we know this baby will not replace the one who died, and yet there is an urgency toward more life, our arms aching and empty.

When Maggie is born, healthy and lively, I am filled with joy and fear. I am on my guard so if she starts to slip away, I can snatch her back. This time I will be ready.

I worry Maggie will suffocate while I nurse her. After she finishes, I put her on my chest, where she falls asleep. I stay awake and count every breath until the birds begin to stir and I know we have made it through another night. I worry, too, that Liam will catch something fatal. My stomach aches, and sometimes I feel dizzy and far away. My church friends tell me to trust God. They tell me they are praying for me.

But Maggie doesn’t die, and spring comes, and she is robust and round, and when her brother makes her laugh, a tiny dimple appears in her right cheek. Then it is another year and another, and I am forgetting altogether about dusting the pictures of Cooper on the mantel.

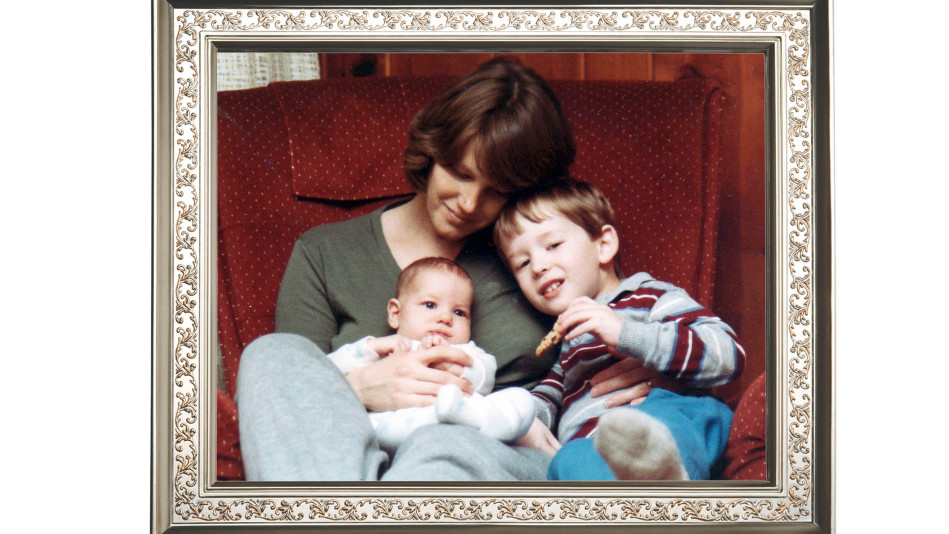

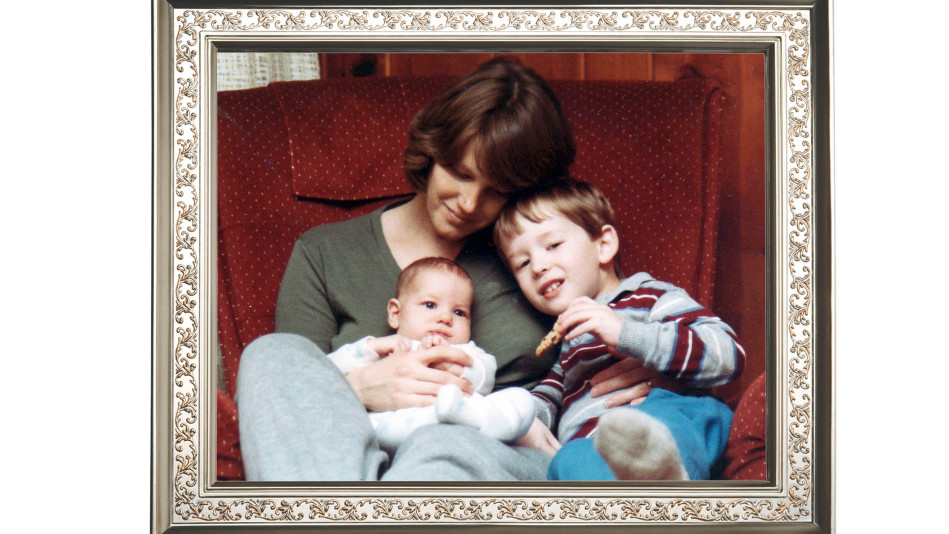

The author with 3-month-old Maggie and 4-year-old Liam, 1984.

By this time, Liam is in kindergarten, and Maggie is in daycare. Now also, faint fault lines begin to show in our marriage’s foundation; grief is the uninvited third party that has refused to leave.

All the while, I attend my Bible study class. I am on a mission now, poring over the scriptures, looking for clues, patterns, a key that unlocks the secret door to the place that holds the answers I seek. At the end of the class, I am still searching.

It is early fall when I enter seminary. I am part scholar, part detective, both parts waiting to be struck like Paul on the road to Damascus, knocked facedown in the dust, then renamed, remade, given new eyes to see some revelation of God woven in the very fabric of the universe. I find I’m good at constructing the theological system. There is a certain satisfying logic to the if-then sequences that I’m able to make solid in my academic essays.

I falter, though, when a friend with headaches is diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor that will take her from her three young children in a couple of years. I lose my footing when a local teen shoots himself one night while sitting on the seminary steps and we come to class the next day to find his blood puddled on the pavement. I can barely stand to watch the devastation on TV; it seems the world is unraveling at its center. I learn Hebrew, deciphering from right to left the cryptic marks on the page, and wait for something to be revealed. I parse Greek sentences, looking for the meaning behind the meaning. I read the Desert Fathers and Mothers, peering through their eyes at ancient sunrises, trying with them to see beyond the far horizon. I study the systematic theologians, listen to their conclusions, weigh and measure them against what I know about babies who slip away in the night.

Always with the same question: Where are You now?

Seven years after Cooper’s death, I begin the supervised chaplaincy I would need to complete in order to be ordained. In our city there are several possible sites: four hospitals, an addiction treatment center, and two nursing care facilities.

One of the sites is the children’s hospital. Many who choose it quit the program before completing it, crushed by the horror of suffering and dying children and their own terrible helplessness in the face of it. I had driven past this hospital each day on my way to the seminary and never without a stab of sadness, recalling Cooper’s tiny form in the bassinet in the corner of the NICU, where the babies were too sick to cry. Since he died, I had been there only once, to visit an ailing niece, and that day I could barely make it through the front doors.

Having counseled me through my ongoing crises of faith, my adviser strongly suggests I cross the site off my list. I know he has good intentions. Still, I feel an overwhelming urge to apply there.

“I can’t explain it,” I tell him as he shakes his head, “but I feel like a fish being reeled in.”

On a blustery day in January, I begin the 20-week program and am assigned to work with children who have infectious diseases, mostly serious respiratory infections and AIDS. I am placed on the Saturday night on-call rotation, which means spending most weekends tethered to my pager and the emergency room. During the first weeks, several children die on my watch: A house fire takes a 3-year-old boy, an aneurysm kills a 4-year-old boy, meningitis ravages the body of a 7-year-old boy, a 5-year-old girl riding without a seat belt is catapulted through a car’s windshield. I am frequently called up to the NICU.

I lose weight, unable to eat more than a few bites at a time, and become exhausted and frequently ill from sleepless overnight shifts, the days and nights bleeding into one another. While I offer prayers for and consolation to frightened children and shattered parents, my raging conversations with God continue, shared only with my colleagues and supervisor.

As part of our instruction, we gather weekly for training with various hospital staff. Halfway through the program, we are visited by a pathologist, a soft-spoken older man who has come to talk with us about the autopsy procedure. Toward the end of the session, he passes around a photocopy of a sample autopsy form, and at the bottom of the page is a familiar signature. This is the man who performed my son’s autopsy.

Later that day I go to the morgue and ask for an appointment. I want to know more; I want to know anything I can know. The pathologist asks me to come back the next day, when he will be better prepared to meet with me.

The following afternoon he shows me into a conference room, sits me at the large table where he has placed Cooper’s full autopsy report, and goes over it, page by page, translating every detail and stopping to answer each of my questions.

When he closes the binder, he turns to me and begins explaining his role in training medical students and his special area of interest, the heart-lung system, describing how he procures and preserves the organs during the autopsy to use them in teaching, injecting them with dye so students can see where problems have occurred and how repairs might be made.

He is quiet for a long moment and then says, “I still have your son’s heart and lungs. Do you want to see them?”

Is it odd to be joyful in such a moment? Do you think it unseemly that my own heart leaps, that I feel an indescribable elation, the breath in me suddenly expansive?

In the brightly lit morgue, the pathologist and I draw on latex gloves and move together to a stainless steel sink, where water is running into a white plastic bucket. Reaching down into the bucket, he brings up all that remains of my son, and in the next instant I hold in my hands the heart that had been inside the infant who had been inside of me.

I peer at the small, gray mismatched lungs and examine the stitches on the aorta, stitches that were sewn in nearly 2,700 days before, while his father and I sat in the waiting room, holding on to each other when we still knew how.

As I cradle my son’s organs, the doctor uses one gloved finger to open the dissected heart, showing me the holes in the septum, the wall between the two atria. “Here, and here, and here,” he says, pointing, and I stare at each in turn, at the defects that in 1982 had been undetectable in our 3-day-old infant, yet powerful enough to kill him.

I stand there for I don’t know how long, breathing in the faint odor of formalin, trying to see what I am seeing, so unreal does it seem that I actually stand holding my son’s remains.

At some point I begin to do a new thing, to move beyond grief and guilt into wonder, to celebrate what I was part of creating— not what was lost but what was alive, what moved and pulsated deep inside of me, what seems to be in some way part of me still.

After a while I hand my son’s organs back to the pathologist, who lowers them into the bucket, where they float like rare creatures of the sea.

Do I believe God led me there to find Cooper’s heart?

Yes.

No.

I don’t know.

What is God, anyway? I am no longer certain, if I ever was. Over the years, visited again by loss—of my marriage, parents, dear friends—I stepped past the boundaries that seek to define where God resides and moved beyond ordained service, beyond church, dancing now along the far borders of what might be called faith.

Here is what I can attest to: I went into a hospital basement broken in certain places and returned mended, restored. I went there thinking I knew what I knew, autopsy report in hand, and discovered I knew next to nothing at all, for here my son had been all along, teaching. And here was my answer: There is no answer. But there is love, the kind that binds us to each other in ways beyond our knowing, ways that span distance, melt time, rupture the membrane between the living and the dead.

I like to imagine we are all of us part of a many-chambered construct that love is continually building, its glimmering hallways winding in and around us, and from time to time an unheard sound comes from another room, noiseless, beyond our comprehension, received as a tug, a whirring in our heads, a flicker in a dream, a vibration along the invisible thread that connects us.

We are troubled, we are stirred, and we are not certain why, but something in us answers.

Rebecca Gummere is chronicling her nine-month cross-country RV trip at ChasingLight-AJourney.com. She's also working on a memoir about the experience.

Photos courtesy of subject

Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the Oprah.com Spirit Newsletter!

More than 40 years ago, Spanish cardiologist Francisco Torrent-Guasp, using his gloved fingers, separated the tissue of a bovine heart at the naturally occurring juncture where the ventricular myocardial band circles around to meet itself. He unfurled the organ, spreading it out flat, a reminder that while for centuries science has continued to treat the heart as a four-chambered construct, there is an added dimension. The heart is also an elegant Gordian knot of one continuous muscle that with each beat contracts and relaxes, pumping blood out and allowing it back in. In the course of one day the adult heart will beat more than 86,000 times, in one year more than 31 million times. By age 70, a human heart will have logged upwards of 2.3 billion contractions, taking cues from the electrical impulses that move through it like lightning up a staircase.

Even the heart of a baby who lives just 42 days will pulsate more than 6 million times before its final, fluttering beat.

“Are you ready?” asks the pathologist.

I nod, making a chalice of my hands, and he reaches down into the plastic bucket and lifts my son’s heart and lungs out of the water. I feel a slight weight, as if I am holding a kitten or a bird.

I blink and the world turns sideways beneath me.

Cooper was born on a Sunday morning in October 1982. In every way, his arrival was ordinary. He was delivered after eight hours of labor; following his first breath, he let out a sharp, lusty cry, his body turning a healthy pink as oxygen moved through his bloodstream. He scored high marks on the standard Apgar newborn assessment. The pediatrician observed that his six-and- a-half-pound birth weight contrasted with that of our first child, Liam, born weighing nearly nine pounds, but she did not appear concerned and made no further comment.

That evening a report came on about a tropical storm that had hit the coast of Central America. Watching the grainy footage of tearing waves and flailing trees, I felt a wrenching, not of physical origin but something deeper, more terrifying, so that my breath came in short bursts. I turned off the television and pushed away the dinner tray. I was being silly, I told myself. Hormones and exhaustion, I thought.

That night Cooper fell asleep partway through his feeding, his mouth working the air for a brief moment before he sank into the crook of my arm. The nurse said some babies need encouragement and suggested I uncover his feet.

On the second day, after his circumcision, Cooper stayed in my room and nursed a little and slept, nursed and slept again. The nurse said he was probably worn out from the procedure.

Cooper, the day after his birth, October 25, 1982.

On the morning of the third day, as we packed to go home, our pediatrician stopped by to say she was “hearing a little heart murmur.” She suggested we take Cooper to the children’s hospital to see her friend, a pediatric cardiologist. She said murmurs are common, that nearly half of all newborns have them. She did not seem overly concerned. “Just to give a listen,” she said, signing the discharge papers.

The cardiologist, a trim man who looked to be in his early 40s, met us in the hospital lobby. We followed him into the elevator and up two floors to his office, where he performed a brief examination, narrowing his eyes as he listened to our son’s heart. Then he draped the stethoscope around his neck and with a quick smile told us he’d like to get some X-rays.

We followed him down a hall and into a room where two technicians were waiting. One took Cooper and held him while I removed his clothing, leaving him in his diaper. She placed him on a small saddle with his arms above his head while a hard plastic case was fastened around his torso, holding him there like the tiny victim of a stickup. He wailed furiously. We watched from a window in the next room as the X-ray machine swiveled around him, capturing images from numerous angles.

After the X-rays, he was taken for an ultrasound. This time my husband and I sat holding hands in the waiting area. It’s probably nothing, we assured each other. They’re just being cautious, we agreed.

When at last we sat in the cardiologist’s office, he placed a chair across from us so that his knees almost touched ours. He held a notepad in one hand, a pen in the other. We moved forward to see what he was drawing, to listen as he deciphered the blue scrawls filling the empty page.

“Do you know what a heart looks like?” he asked, and I remember having one distinct thought: We should run.

Outside in the bright October day, traffic hummed along as if everything were normal, as if I were not holding a baby whose blood pressure was at once too high and too low, blood backed up in some vessels like a clogged river, slowing to a trickle in others, whose aorta narrowed to the width of a sewing thread just below the heart, whose lungs were compressed by his enlarged right atrium and ventricle.

Early the next morning, we returned to hand him over again, this time to a lion of a man with massive hands and a mane of graying reddish hair, a pediatric heart surgeon who—while we paced like animals in a crowded waiting room awash in the smells of French fries and cigarette smoke and body odor—would make a long, delicate incision in our son’s small torso, beginning just under the sternum and traversing the left side of his body around to the back, removing the scalpel just under the left shoulder blade. He would pull back the flesh and uncover the mistake, cut out the narrowed section and resect the aorta so blood would flow unimpeded and pressure would stabilize, and the small heart that had been working so hard could ease into a sure and steady rhythm.

Six hours later, the surgeon came to find us. “Everything went fine,” he said. I wept into his broad chest.

In the NICU—the neonatal intensive care unit—there was neither night nor day but another kind of time altogether. In a far corner of that too-bright room was a plastic bassinet, and inside lay Cooper, his eyes wide with shock and pain.

Four days later, my husband and I were able to hold him. The next day I was able to nurse him. When we brought him home on the tenth day, he had already gained a pound, and once he was in a regular feeding routine, he was able to sleep. His cheeks grew round, and he kicked his legs in excitement.

I let myself breathe.

On an overcast morning in early December, Cooper, now 6 weeks old, wakened fretful and vomited after his morning feeding. My husband was away on a business trip, so I dropped off Liam at a friend’s and took Cooper to our pediatrician. She gave him a thorough examination, listening intently to his heart, his lungs, his pulse points—all, she said, sounding normal. She thought he had likely picked up a virus and prescribed electrolyte fluids and rest.

Back home he continued to fuss, ate little, and toward evening had a short bout of diarrhea. After Liam was in bed, I called my husband, who was preparing to board his overnight return flight. We chatted about his predawn arrival and the trip he’d been on—anything to avoid naming our fear. Then I sat in the quiet house and listened to the ticking mantel clock and rocked Cooper, and after a time he quieted and was able to take a little fluid, and we both dozed in the chair.

Then this: He wakes, fussing, squirming. I change his diaper and notice he is cool, so cool to the touch, and his skin has gone white, his surgical scar now a harsh purple line against his pale torso.

And then: I am on the phone with the pediatrician, hating to bother her because it is nearly 11 at night, hating to be so inept, but I tell her about this new thing, this coolness, and she says, “Try putting him in a warm bath and see if that doesn’t help.”

So I do. And it calms us both, but now I cry, too, afraid and very tired, and I talk to him between my fits of weeping, saying, “There. Isn’t that nice? Doesn’t that feel good? Aren’t you better?” He lies in the tub without kicking or moving, looking up at me. I listen to his quiet breathing and watch his dark eyes watching me.

I dry him off and dress him in a pine green fleece romper and tuck him inside a cotton flannel receiving blanket and then wrap a crocheted afghan around him. I bring him downstairs and rock him some more. Now he sleeps, but I am unsettled. His face feels so cool. I call the pediatrician again.

“Okay,” she says, “let’s put him back in the hospital till he gets over this,” and tells me she will meet us there.

I call my neighbor Jerry to come take Liam to their house. I call my sister-in-law to come with me to the hospital. I put Cooper on the sofa. I notice his lungs sound congested, and this is concerning, this rattling sound is new, but he is resting at last, so I lay him next to a cushion and run upstairs to pull Liam from his bed, and he is sleeping so hard, he cannot wake up. His legs buckle; he’s just 2 years old, but I struggle to hold up his dead weight as I try to dress him. I carry him downstairs, where I place him on the shag carpet and slide his arms into his winter jacket, stuff his limp feet into his boots, pull his hat onto his head. He sleeps through it all.

My neighbor arrives. I am saying things like “the baby” and “my sister-in-law” and “the hospital.” Everything is whirling.

And then in an instant I feel a terrible pulling inside me. I let Liam slide to the floor and look across the room at Cooper.

“He is not breathing,” I say, and I know it is true.

“What?” Jerry is confused.

“He’s not breathing.” I run to the sofa, peel away the layers, unzip the fleece, draw up his undershirt. Lay my ear to his cool chest. All I hear is the thud of my own heart. I take a deep breath, lift my head, place it on his chest again.

“Call 911,” I shout, and then everything is changed.

I hold him, panicked, try to breathe into his mouth, try to push on his small chest, but I don’t know what I’m doing, so instead I rock him and I whisper because I have no voice. “Please, God, not my baby, not my baby. Please don’t take my baby.”

The door bangs open. For a moment there is confusion. At first the EMTs go to Liam, asleep on the floor, thinking he is the one in distress.

I cannot speak, hunched over Cooper, trying to breathe for both of us.

“Over here,” yells Jerry.

They take Cooper from me, put him on the dining room table, a table I will later have to give away. They listen and look and listen some more, for a long time, with grim faces.

At last one of the paramedics pronounces what we all know: “This baby is deceased.”

A sob escapes from one of the squad members, a young dark-haired man, and he wipes his eyes. “I’m so sorry,” he says.

My husband arrives home sometime before 4 in the morning. I meet him at the door. He sees my face and behind me our pastor and the pediatrician and friends and neighbors, and he shakes his head, saying no, and refusing to come inside, putting his hand out and saying no, no, and no. Then his legs give way and he falls to his knees. We kneel together on our front porch, first light creeping from the east.

When the coroner arrives, my husband and I hold our baby and stroke the blanket covering his small, cold body. We kiss his forehead and tell him we love him, and we hand him over one last time.

Since he has died at home, an autopsy is mandatory. We are devastated to think of him being cut open again, but we have no say in the matter, and we sign the papers, allowing the hospital to do what it must.

Liam sits next to me on the sofa and asks again where the baby has gone, and I tell him again that the baby was very sick, and it was a kind of sick that couldn’t get better, but it’s not a kind of sick you can catch, you are fine. But the baby was sick and the baby died and now he is in heaven with God. I tell Liam God is taking good care of our baby, but I am not sure I believe it, not sure at all.

I want God to be real. I need there to be Someone in charge, and I need there to be a heaven, some place where I know my baby is safe and cared for and loved. I think back to when I was a child, moments when I sensed a presence—at 8, seated between my mother and sister in a church pew, the sun painting my leg in reds and golds and blues, believing God was somehow in that dance of color; at 12, perched on a hillside as a wild wind stirred then quieted in the field behind me, and then in the utter stillness came the piercing call of one lone bird, sending chills over my skin, the very voice of God in my ear.

Where are You now? I wonder. Friends from a Bible study I’ve recently joined come to sit with me, read psalms, offer prayers against the descending darkness. Where are You now?

Sometimes, late in the afternoon when Liam is napping and the house is quiet, I hear a baby’s cries coming as if from some distant room. I startle each time before I remember what my doctor has told me, that these are “phantom cries,” common with women who have lost a child.

In time the phantom crying ceases. I clean Cooper’s room and box up his clothing, keeping his cotton hospital blanket and a small stuffed bear, and some days I sit in the rocker and hold them close to me.

Six months later, I am pregnant again. My husband and I are terrified at the thought of another loss, and we know this baby will not replace the one who died, and yet there is an urgency toward more life, our arms aching and empty.

When Maggie is born, healthy and lively, I am filled with joy and fear. I am on my guard so if she starts to slip away, I can snatch her back. This time I will be ready.

I worry Maggie will suffocate while I nurse her. After she finishes, I put her on my chest, where she falls asleep. I stay awake and count every breath until the birds begin to stir and I know we have made it through another night. I worry, too, that Liam will catch something fatal. My stomach aches, and sometimes I feel dizzy and far away. My church friends tell me to trust God. They tell me they are praying for me.

But Maggie doesn’t die, and spring comes, and she is robust and round, and when her brother makes her laugh, a tiny dimple appears in her right cheek. Then it is another year and another, and I am forgetting altogether about dusting the pictures of Cooper on the mantel.

The author with 3-month-old Maggie and 4-year-old Liam, 1984.

By this time, Liam is in kindergarten, and Maggie is in daycare. Now also, faint fault lines begin to show in our marriage’s foundation; grief is the uninvited third party that has refused to leave.

All the while, I attend my Bible study class. I am on a mission now, poring over the scriptures, looking for clues, patterns, a key that unlocks the secret door to the place that holds the answers I seek. At the end of the class, I am still searching.

It is early fall when I enter seminary. I am part scholar, part detective, both parts waiting to be struck like Paul on the road to Damascus, knocked facedown in the dust, then renamed, remade, given new eyes to see some revelation of God woven in the very fabric of the universe. I find I’m good at constructing the theological system. There is a certain satisfying logic to the if-then sequences that I’m able to make solid in my academic essays.

I falter, though, when a friend with headaches is diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor that will take her from her three young children in a couple of years. I lose my footing when a local teen shoots himself one night while sitting on the seminary steps and we come to class the next day to find his blood puddled on the pavement. I can barely stand to watch the devastation on TV; it seems the world is unraveling at its center. I learn Hebrew, deciphering from right to left the cryptic marks on the page, and wait for something to be revealed. I parse Greek sentences, looking for the meaning behind the meaning. I read the Desert Fathers and Mothers, peering through their eyes at ancient sunrises, trying with them to see beyond the far horizon. I study the systematic theologians, listen to their conclusions, weigh and measure them against what I know about babies who slip away in the night.

Always with the same question: Where are You now?

Seven years after Cooper’s death, I begin the supervised chaplaincy I would need to complete in order to be ordained. In our city there are several possible sites: four hospitals, an addiction treatment center, and two nursing care facilities.

One of the sites is the children’s hospital. Many who choose it quit the program before completing it, crushed by the horror of suffering and dying children and their own terrible helplessness in the face of it. I had driven past this hospital each day on my way to the seminary and never without a stab of sadness, recalling Cooper’s tiny form in the bassinet in the corner of the NICU, where the babies were too sick to cry. Since he died, I had been there only once, to visit an ailing niece, and that day I could barely make it through the front doors.

Having counseled me through my ongoing crises of faith, my adviser strongly suggests I cross the site off my list. I know he has good intentions. Still, I feel an overwhelming urge to apply there.

“I can’t explain it,” I tell him as he shakes his head, “but I feel like a fish being reeled in.”

On a blustery day in January, I begin the 20-week program and am assigned to work with children who have infectious diseases, mostly serious respiratory infections and AIDS. I am placed on the Saturday night on-call rotation, which means spending most weekends tethered to my pager and the emergency room. During the first weeks, several children die on my watch: A house fire takes a 3-year-old boy, an aneurysm kills a 4-year-old boy, meningitis ravages the body of a 7-year-old boy, a 5-year-old girl riding without a seat belt is catapulted through a car’s windshield. I am frequently called up to the NICU.

I lose weight, unable to eat more than a few bites at a time, and become exhausted and frequently ill from sleepless overnight shifts, the days and nights bleeding into one another. While I offer prayers for and consolation to frightened children and shattered parents, my raging conversations with God continue, shared only with my colleagues and supervisor.

As part of our instruction, we gather weekly for training with various hospital staff. Halfway through the program, we are visited by a pathologist, a soft-spoken older man who has come to talk with us about the autopsy procedure. Toward the end of the session, he passes around a photocopy of a sample autopsy form, and at the bottom of the page is a familiar signature. This is the man who performed my son’s autopsy.

Later that day I go to the morgue and ask for an appointment. I want to know more; I want to know anything I can know. The pathologist asks me to come back the next day, when he will be better prepared to meet with me.

The following afternoon he shows me into a conference room, sits me at the large table where he has placed Cooper’s full autopsy report, and goes over it, page by page, translating every detail and stopping to answer each of my questions.

When he closes the binder, he turns to me and begins explaining his role in training medical students and his special area of interest, the heart-lung system, describing how he procures and preserves the organs during the autopsy to use them in teaching, injecting them with dye so students can see where problems have occurred and how repairs might be made.

He is quiet for a long moment and then says, “I still have your son’s heart and lungs. Do you want to see them?”

Is it odd to be joyful in such a moment? Do you think it unseemly that my own heart leaps, that I feel an indescribable elation, the breath in me suddenly expansive?

In the brightly lit morgue, the pathologist and I draw on latex gloves and move together to a stainless steel sink, where water is running into a white plastic bucket. Reaching down into the bucket, he brings up all that remains of my son, and in the next instant I hold in my hands the heart that had been inside the infant who had been inside of me.

I peer at the small, gray mismatched lungs and examine the stitches on the aorta, stitches that were sewn in nearly 2,700 days before, while his father and I sat in the waiting room, holding on to each other when we still knew how.

As I cradle my son’s organs, the doctor uses one gloved finger to open the dissected heart, showing me the holes in the septum, the wall between the two atria. “Here, and here, and here,” he says, pointing, and I stare at each in turn, at the defects that in 1982 had been undetectable in our 3-day-old infant, yet powerful enough to kill him.

I stand there for I don’t know how long, breathing in the faint odor of formalin, trying to see what I am seeing, so unreal does it seem that I actually stand holding my son’s remains.

At some point I begin to do a new thing, to move beyond grief and guilt into wonder, to celebrate what I was part of creating— not what was lost but what was alive, what moved and pulsated deep inside of me, what seems to be in some way part of me still.

After a while I hand my son’s organs back to the pathologist, who lowers them into the bucket, where they float like rare creatures of the sea.

Do I believe God led me there to find Cooper’s heart?

Yes.

No.

I don’t know.

What is God, anyway? I am no longer certain, if I ever was. Over the years, visited again by loss—of my marriage, parents, dear friends—I stepped past the boundaries that seek to define where God resides and moved beyond ordained service, beyond church, dancing now along the far borders of what might be called faith.

Here is what I can attest to: I went into a hospital basement broken in certain places and returned mended, restored. I went there thinking I knew what I knew, autopsy report in hand, and discovered I knew next to nothing at all, for here my son had been all along, teaching. And here was my answer: There is no answer. But there is love, the kind that binds us to each other in ways beyond our knowing, ways that span distance, melt time, rupture the membrane between the living and the dead.

I like to imagine we are all of us part of a many-chambered construct that love is continually building, its glimmering hallways winding in and around us, and from time to time an unheard sound comes from another room, noiseless, beyond our comprehension, received as a tug, a whirring in our heads, a flicker in a dream, a vibration along the invisible thread that connects us.

We are troubled, we are stirred, and we are not certain why, but something in us answers.

Rebecca Gummere is chronicling her nine-month cross-country RV trip at ChasingLight-AJourney.com. She's also working on a memoir about the experience.

Photos courtesy of subject

Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the Oprah.com Spirit Newsletter!