Roughly 90 percent of white women with breast cancer will survive five years after diagnosis. Only 79 percent of black women will. But even as the mortality gap persists, a small army of passionate advocates are proving this is a failure we can avoid.

Illustration: Rebekka Dunlap

In a quiet little cubicle tucked inside a boxy glass building in Chicago's medical district, a tall young woman in a long skirt and a white nursing coat picks up the phone. "Hi, this is DeShuna Dickens calling on behalf of South Shore Hospital about your mammogram results," she says in a practiced, even tone. "The radiologist is recommending you come back for additional testing. Have you had a chance to make an appointment?" Dickens listens as the patient on the other end explains why she hasn't followed up—some women never received their initial test results in the mail; others said they've been too busy—then offers to help arrange further testing. When the conversation ends, she makes a few detailed notes in her files, then moves on to the next patient in her stack.

Dickens barely looks old enough to have earned two master's degrees (one in public health, the other in nursing)—and she certainly doesn't look weary enough to have been doing this job for more than a year: Every day she spends hours making calls just like this one, imploring women to follow up with their doctor and explaining the process of managing their care. She helps them schedule appointments, change doctors and wade through insurance issues. Occasionally, she even goes to doctors' visits with those who need extra support. "I recently worked with one woman who was so scared and overwhelmed that I offered to go with her to her biopsy," Dickens tells me on a sunny summer morning. "It helps to have someone there who can understand the terminology and make sure you are clear on the treatment plan."

Dickens does this on behalf of three community hospitals in Chicago that, for one reason or another, lack the resources to do their own follow-up with all their at-risk patients. "One hospital I work with had a binder of at least 75 women with suspicious or incomplete test results, going back as far as 2012," Dickens says. "Women in some communities are falling through the cracks."

Related Stories | |

|---|---|

|  |

At Risk in Your State? | Against Breast Cancer |

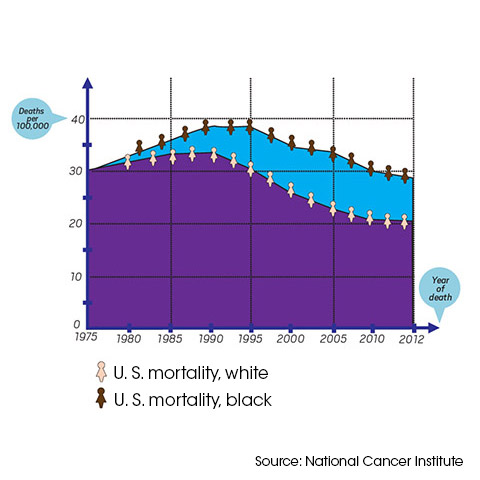

But it's not just "some" communities—specifically, it's black communities. Right now in America, black women are about 40 percent likelier to die from breast cancer than white women, despite the fact that they're less likely to get the disease in the first place. That translates to an estimated 1,710 black women each year, according to groundbreaking research released in 2014 by the Sinai Urban Health Institute and the Avon Foundation Breast Cancer Crusade. And the study found that between 1990 and 2009, in cities from Memphis to Los Angeles, the black-white survival gap actually grew. Thirty years ago, black and white women died of breast cancer at about the same rate, but as treatment and screenings improved, more white women survived the disease while the death rate among black women stayed stubbornly higher. "It's disgraceful how many black women are dying unnecessarily," says Anne Marie Murphy, PhD, former director of healthcare initiatives for the Illinois governor.

In 2007, a group of doctors, researchers, and community activists in Chicago, alarmed by the trend, launched Equal Hope (formerly the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force), an independent research and advocacy group that focuses exclusively on eradicating racial disparities in breast cancer. (Murphy is its executive director.) They wanted answers: Why the deadly gap? And what to do about it? Initially, some experts wrote them off, believing the mortality gap to be rooted in biological differences and therefore largely insoluble. But while it's true that African American women have higher rates of aggressive breast tumors known as triple-negative (for which there are no targeted treatments) and a higher prevalence of some breast cancer–related gene mutations, those differences don't account for the sheer size of the problem, says David Ansell, MD, a senior vice president at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and cofounder of the task force. In fact, the overall breast cancer incidence among black women is nearly 4 percentage points lower than in white women. Nor does biology explain the geographic variance in death rates, even between cities in the same state. (While black and white breast cancer patients in Sacramento fare about the same, black women in Los Angeles are 71 percent more likely to die than white women, according to the Sinai/Avon study.)

Others questioned whether the problem isn't so much a race issue as a matter of socioeconomics—those with more money survive while those with less die. The truth, according to many experts I spoke with, is that racial health disparities are attributed to biology, poverty, and race—specifically, America's legacy of racial segregation. In predominantly black Chicago neighborhoods, not a single hospital or clinic has earned the American College of Radiology's Breast Imaging Center of Excellence seal of approval, and only one carries Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation from the American College of Surgeons. Nonaccredited treatment centers typically use older equipment, employ fewer breast imaging specialists, and miss more incidences of cancer than hospitals like Rush and University of Chicago, both of which are accredited and are located in whiter neighborhoods. Breast imaging specialists—radiologists who spend a majority of their time reading mammograms and often have specialized training—are almost twice as likely as general radiologists to pinpoint cancer in a mammogram. In other words, even if women of color do all the right things—go for routine testing, schedule follow-up appointments—they can still fare worse than white women simply by virtue of where they live.

As screenings and treatments for breast cancer improved in the United States, a gap in care developed.

Before Provident Hospital of Cook County—a public treatment facility that serves a majority black population—stopped offering mammograms in June, the conditions in its mammography unit were deplorable. I saw a photo of a manhole cover—which I'm told had an active sewer running beneath it—smack in the middle of the room where technicians read mammography films. The fumes were reportedly so strong at times that staffers had to wear surgical masks. (A rep for Provident Hospital admits that sewer fumes are known to be a problem in the building and says plans for a new state-of-the-art mammography center are under way.) "All you have to do is look at some of these neighborhood hospitals to know how different they are from the large, well-funded ones," says Teena Francois-Blue, the task force's associate director of community health initiatives and research.

Illustration: Rebekka Dunlap

To make matters worse, studies suggest that doctors can be influenced by a patient's race and that this bias can affect treatment decisions, such as whether to offer a patient an aggressive or a complex treatment. While overt racism in physicians is rare, Ansell cowrote in an editorial published earlier this year in The New England Journal of Medicine, a growing body of research has detected a subconscious preference among doctors for white patients compared with black patients.

How does this bias play out in black lives? African Americans are less likely than whites to receive recommended medications and treatments for illnesses from HIV/AIDS to heart disease to diabetes, even when they have the same insurance. That isn't Ansell's opinion; it's straight from a report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), a nonprofit established to provide objective healthcare information, often at the direct request of federal agencies and Congress. The bottom line, according to the IOM: There's "strong, but circumstantial, evidence for the role of bias, stereotyping and prejudice" in racial health disparities.

Yet the task force takes heart from the otherwise bleak findings, since the research confirms what they've long believed: that the black-white mortality gap is fixable. Racial disparity can be reduced—and possibly eliminated—when black women with breast cancer get access to the same level of care as white women. "We don't need a magic bullet to fix this," says Patricia Ganz, MD, a member of the Breast Cancer Research Foundation Scientific Advisory Board and professor of medicine and public health at UCLA. "We just need to give black women the same standard of care." All it takes is awareness, manpower, money and buy-in from a city's healthcare community.

That's exactly what the Chicago task force set out to secure, first parsing the city's breast cancer survival statistics to see just how bad the mortality gap was. Then, with significant funding from the Avon Foundation for Women and Susan G. Komen, the grassroots team persuaded 160 healthcare providers across the state to share their data, such as tumor detection rates. The group also identified hospitals with undertrained mammography technicians or radiologists who weren't breast imaging specialists and arranged free continuing education courses. And perhaps most important, they launched their patient navigation program, in which a staff of six fields calls from and gives guidance to more than 1,400 women in need of care every year. Navigators steer their charges to the city's highest-quality medical centers, even if those hospitals are 60 minutes and two bus transfers away; they call doctors' offices to request records or schedule visits and make sure clients get there. In one Chicago institution, the task force observed that women weren't going back to get diagnostic mammograms, Ansell recalls. "So we investigated and learned that the phone number the women were told to call had no one there to pick up." Discoveries like this are what led the task force to partner with hospitals that don't have adequate follow-up programs in place.

It was as a navigator that DeShuna Dickens reached out to Gerri Murrah in May. When a lump in Murrah's right breast became swollen and sore, she'd gone to the emergency room. The doctor didn't even suspect cancer; she was given antibiotics and sent home. When the lump persisted, Murrah, 60, went to a different clinic and requested a mammogram. The results were suspicious, and it was at this point that Murrah's file ended up on Dickens's desk. While the two traded voicemails, Murrah was assigned to a surgeon at a community hospital who made two blunders: Instead of doing a needle biopsy, per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, he surgically removed the lump—a procedure both costlier and more painful. Then, without even telling Murrah the stage of her breast cancer (it was stage III), he recommended a mastectomy. When Dickens finally got hold of Murrah, she suggested Murrah see a top surgeon at the University of Chicago for a second opinion. There, Murrah learned she didn't need a mastectomy. "DeShuna came in just in time to stop me from having my breast cut off," she says, angry and grateful at the same time.

Daphne Johnson feels equally indebted to the task force. Three years ago, Johnson, now 54, found herself suddenly laid off from her job at Hewlett-Packard. "For the first time since college, I was without insurance, and I didn't know what to do when it was time for my annual mammogram," she says. "A friend told me there were ways to get free screenings, so I called a hospital I'd been to in the past." The hospital gave her the task force's number, and a staffer quickly set Johnson up with a free screening. When the results came back suspicious, Johnson's navigator, Yomaira Molina, arranged for a second mammogram, an ultrasound, and eventually a needle biopsy at the University of Chicago. That test confirmed that the lump in Johnson's right breast was stage II cancer. While Johnson digested the diagnosis and broke the news to her family and friends, Molina took charge, getting her signed up for Medicaid, which covered the rest of her costly cancer treatments. "I'm so grateful to have received such amazing care," says Johnson now, looking robust and relieved after a lumpectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy, sporting a chic close-cropped haircut. "I don't even want to think about what might have happened had I not been connected with the task force."

Johnson and Murrah, who just began chemo herself, are prime examples of the task force's dramatic impact. In just two years—between 2008 and 2010 (the most recent data available)—breast cancer deaths among black women in Chicago fell by an incredible 35 percent. What makes the task force's success even more remarkable is that the programs are so simple: Find women who are falling through the cracks of the healthcare system and connect them with better care.

Now major cities across the U.S. are taking steps to replicate the task force's work. "I sob sometimes when I get off the phone with these women," says Elaine Hare, whose three-person staff at the Memphis-Midsouth chapter of Susan G. Komen helps arrange free mammograms and biopsies for thousands of women. Hare is a founding member of the fledging Memphis Consortium, a group of advocates and public health experts who want to create a task force–like program; in that city, black breast cancer patients are roughly twice as likely to die as whites.

Initial efforts in Memphis—and similar initiatives in Houston, Boston, and Los Angeles—consist of essential baby steps like community research and awareness campaigns. But that doesn't mean advocates aren't dreaming big. On task force director Anne Marie Murphy's wish list: a revised federal Mammogram Quality Standards Act that would hold hospitals and clinics accountable for the quality of their mammograms and their ability to interpret them; bipartisan legislators to champion it; and a law that would require Medicare, Medicaid and insurers in every state to include at least one CoC-accredited program and one ACR Center of Excellence in their network. "It's sad that we even have to ask for this," says Murphy. "These women's lives matter."

Sunny Sea Gold is a health writer living in Portland, Oregon.

How does this bias play out in black lives? African Americans are less likely than whites to receive recommended medications and treatments for illnesses from HIV/AIDS to heart disease to diabetes, even when they have the same insurance. That isn't Ansell's opinion; it's straight from a report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), a nonprofit established to provide objective healthcare information, often at the direct request of federal agencies and Congress. The bottom line, according to the IOM: There's "strong, but circumstantial, evidence for the role of bias, stereotyping and prejudice" in racial health disparities.

Yet the task force takes heart from the otherwise bleak findings, since the research confirms what they've long believed: that the black-white mortality gap is fixable. Racial disparity can be reduced—and possibly eliminated—when black women with breast cancer get access to the same level of care as white women. "We don't need a magic bullet to fix this," says Patricia Ganz, MD, a member of the Breast Cancer Research Foundation Scientific Advisory Board and professor of medicine and public health at UCLA. "We just need to give black women the same standard of care." All it takes is awareness, manpower, money and buy-in from a city's healthcare community.

That's exactly what the Chicago task force set out to secure, first parsing the city's breast cancer survival statistics to see just how bad the mortality gap was. Then, with significant funding from the Avon Foundation for Women and Susan G. Komen, the grassroots team persuaded 160 healthcare providers across the state to share their data, such as tumor detection rates. The group also identified hospitals with undertrained mammography technicians or radiologists who weren't breast imaging specialists and arranged free continuing education courses. And perhaps most important, they launched their patient navigation program, in which a staff of six fields calls from and gives guidance to more than 1,400 women in need of care every year. Navigators steer their charges to the city's highest-quality medical centers, even if those hospitals are 60 minutes and two bus transfers away; they call doctors' offices to request records or schedule visits and make sure clients get there. In one Chicago institution, the task force observed that women weren't going back to get diagnostic mammograms, Ansell recalls. "So we investigated and learned that the phone number the women were told to call had no one there to pick up." Discoveries like this are what led the task force to partner with hospitals that don't have adequate follow-up programs in place.

It was as a navigator that DeShuna Dickens reached out to Gerri Murrah in May. When a lump in Murrah's right breast became swollen and sore, she'd gone to the emergency room. The doctor didn't even suspect cancer; she was given antibiotics and sent home. When the lump persisted, Murrah, 60, went to a different clinic and requested a mammogram. The results were suspicious, and it was at this point that Murrah's file ended up on Dickens's desk. While the two traded voicemails, Murrah was assigned to a surgeon at a community hospital who made two blunders: Instead of doing a needle biopsy, per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, he surgically removed the lump—a procedure both costlier and more painful. Then, without even telling Murrah the stage of her breast cancer (it was stage III), he recommended a mastectomy. When Dickens finally got hold of Murrah, she suggested Murrah see a top surgeon at the University of Chicago for a second opinion. There, Murrah learned she didn't need a mastectomy. "DeShuna came in just in time to stop me from having my breast cut off," she says, angry and grateful at the same time.

Daphne Johnson feels equally indebted to the task force. Three years ago, Johnson, now 54, found herself suddenly laid off from her job at Hewlett-Packard. "For the first time since college, I was without insurance, and I didn't know what to do when it was time for my annual mammogram," she says. "A friend told me there were ways to get free screenings, so I called a hospital I'd been to in the past." The hospital gave her the task force's number, and a staffer quickly set Johnson up with a free screening. When the results came back suspicious, Johnson's navigator, Yomaira Molina, arranged for a second mammogram, an ultrasound, and eventually a needle biopsy at the University of Chicago. That test confirmed that the lump in Johnson's right breast was stage II cancer. While Johnson digested the diagnosis and broke the news to her family and friends, Molina took charge, getting her signed up for Medicaid, which covered the rest of her costly cancer treatments. "I'm so grateful to have received such amazing care," says Johnson now, looking robust and relieved after a lumpectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy, sporting a chic close-cropped haircut. "I don't even want to think about what might have happened had I not been connected with the task force."

Johnson and Murrah, who just began chemo herself, are prime examples of the task force's dramatic impact. In just two years—between 2008 and 2010 (the most recent data available)—breast cancer deaths among black women in Chicago fell by an incredible 35 percent. What makes the task force's success even more remarkable is that the programs are so simple: Find women who are falling through the cracks of the healthcare system and connect them with better care.

Now major cities across the U.S. are taking steps to replicate the task force's work. "I sob sometimes when I get off the phone with these women," says Elaine Hare, whose three-person staff at the Memphis-Midsouth chapter of Susan G. Komen helps arrange free mammograms and biopsies for thousands of women. Hare is a founding member of the fledging Memphis Consortium, a group of advocates and public health experts who want to create a task force–like program; in that city, black breast cancer patients are roughly twice as likely to die as whites.

Initial efforts in Memphis—and similar initiatives in Houston, Boston, and Los Angeles—consist of essential baby steps like community research and awareness campaigns. But that doesn't mean advocates aren't dreaming big. On task force director Anne Marie Murphy's wish list: a revised federal Mammogram Quality Standards Act that would hold hospitals and clinics accountable for the quality of their mammograms and their ability to interpret them; bipartisan legislators to champion it; and a law that would require Medicare, Medicaid and insurers in every state to include at least one CoC-accredited program and one ACR Center of Excellence in their network. "It's sad that we even have to ask for this," says Murphy. "These women's lives matter."

Sunny Sea Gold is a health writer living in Portland, Oregon.