Photo: Alessandra Petlin

What's the most treacherous ground for a mother and daughter to navigate? Robin Marantz Henig and daughter Jess Zimmerman weigh in.

The Mother's Story"I wanted to spare her pain."

Watching my daughter belly dance last year brought tears to my eyes. Jess was 28 at the time, and she was splendid. She wore a costume of bright blue and a gold hip scarf with jiggling coins. Her midriff—also jiggling—was bare. She was graceful in her shimmies, graceful with her arms, graceful when she flicked her naked feet. I loved watching her.

All the years of sitting through the plays of Jess's childhood came back to me, plays in which she spoke her lines in a sweet, clear voice but could never get over the awkwardness of being herself. I had thought that at the heart of Jess's discomfort, on stage and off, was the fact that she felt bad about being fat. Yet everything I did to spare her insecurity about her weight turned out to be a source of pain for her—and a thorn at the heart of our relationship that we're still trying delicately to extract.

As a baby, Jessie was spectacular. Huge blue-gray eyes, a corona of golden curls—my husband, Jeff, and I were delighted with the way she looked, the way she laughed, the way she smelled. To us, she was perfect.

Which is why I was so surprised by an offhand comment made one evening at a local restaurant. The owner's wife was fussing over Jessie, who was about 9 months old. "Ooooh," the woman said happily, "I love fat babies."

Fat babies? What baby was she talking about? My baby? I had a fat baby?

I was 26 at the time, and I had body issues of my own. Growing up, I was always aware of being chunkier than other girls, and the misery that came with that awareness had never quite left me. I didn't want my little girl to grow up with that kind of unhappiness. Maybe—smarter in 1980 than my mother had been in 1953—there was something I could do to spare her that psychic pain.

By the age of 4, Jessie weighed ten pounds more than the charts said she should. Not fat, just chubby—and I knew I shouldn't overreact. "I'm trying very hard to ignore it," I wrote in my journal, "so I don't make her self-conscious and create a problem where there is none."

Of course, that's exactly what I did: create a problem where there was none. I was on the heavy end of my own lifelong weight-seesaw then; our second daughter, Samantha, had just been born, and my postpregnancy weight was stubbornly hanging on. When I dreamed one night that I was shopping at a plus-size store, I woke up in a panic. In the grip of this self-disgust, I turned to my beautiful Jessie and decided I had to fix her.

Meals soon became a battleground. I packed abstemious school lunches—half a sandwich, a fruit, no junk—and used smaller plates at dinner to limit her portion size. I hid the cookies I bought for Sam, and wouldn't tell Jessie where they were. And when Jessie asked for seconds, I'd say, "Are you really hungry?" I thought that sounded supportive. I see now how harsh it was. If she asked for the food, she was hungry. I should at least have trusted her to know her own body's cues.

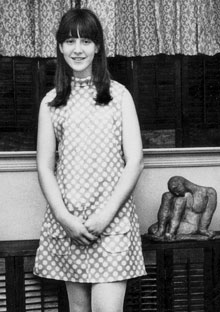

Robin, at age 13

I should pause here to point out that despite my body-loathing, I'm not fat. My BMI is at the low end of the "healthy" range, I wear a size 8, and because I'm flat-chested I give off a pretty slim vibe.

But when I look in the mirror, what I see is not a small waist but massive thighs. When I was 21, I wrote a list on yellow legal paper: "What I need to be happy." Years later I found it again, crinkled with age. At the top of the list, number one—ahead of a rewarding career, a loving family, a house with lots of windows—is the single thing I thought would make the rest of my life fall into place: thin thighs. I wrote that list a long time ago. I am 56 years old, I still don't have thin thighs, and, dammit, I still want them.

Things were tough for us when Jessie was in her early teens—tougher than they were for the typical mother and teenage daughter. When I took her to a dermatologist to be treated for acne, she had a tantrum in the waiting room. I was mystified. I didn't see that this doctor visit was, to Jessie, yet another indication that my love was conditional. She thought I loved her only when she was clear-skinned and slim.

When she was 16, Jess—she had by then put a stop to "Jessie"—sat me down one night and told me she'd been bulimic for years. My first thought was she couldn't be, or she wouldn't be so fat. But I held my tongue and listened as she told me that it was my fault. She was bulimic, she said, because of my emphasis on being thin, my embarrassing comments about food in front of her friends, my obvious disappointment in her body.

"I'm not disappointed in your body," I said. "I think you're beautiful." Jess looked at me skeptically. "I do," I insisted. "Your eyes, your hair, your manner, everything about who you are—it's all beautiful." But my perceptive daughter heard the roar of words unsaid. I never said "your body," because to say I found it beautiful would have been a lie.

The summer after her freshman year in college, when she was 18, Jess suggested we try Weight Watchers together. I leaped at the chance, and we bonded over food restriction, each losing about 20 pounds. But by Thanksgiving Jess had regained every pound. I saw this as a setback. I failed to see what was really happening: that by eating normally instead of dieting, she was finally learning to love her body, however fat or lumpy. This emerging attitude was about to transform not only her relationship with herself but our fractious mother-daughter relationship, too.

But when I look in the mirror, what I see is not a small waist but massive thighs. When I was 21, I wrote a list on yellow legal paper: "What I need to be happy." Years later I found it again, crinkled with age. At the top of the list, number one—ahead of a rewarding career, a loving family, a house with lots of windows—is the single thing I thought would make the rest of my life fall into place: thin thighs. I wrote that list a long time ago. I am 56 years old, I still don't have thin thighs, and, dammit, I still want them.

Things were tough for us when Jessie was in her early teens—tougher than they were for the typical mother and teenage daughter. When I took her to a dermatologist to be treated for acne, she had a tantrum in the waiting room. I was mystified. I didn't see that this doctor visit was, to Jessie, yet another indication that my love was conditional. She thought I loved her only when she was clear-skinned and slim.

When she was 16, Jess—she had by then put a stop to "Jessie"—sat me down one night and told me she'd been bulimic for years. My first thought was she couldn't be, or she wouldn't be so fat. But I held my tongue and listened as she told me that it was my fault. She was bulimic, she said, because of my emphasis on being thin, my embarrassing comments about food in front of her friends, my obvious disappointment in her body.

"I'm not disappointed in your body," I said. "I think you're beautiful." Jess looked at me skeptically. "I do," I insisted. "Your eyes, your hair, your manner, everything about who you are—it's all beautiful." But my perceptive daughter heard the roar of words unsaid. I never said "your body," because to say I found it beautiful would have been a lie.

The summer after her freshman year in college, when she was 18, Jess suggested we try Weight Watchers together. I leaped at the chance, and we bonded over food restriction, each losing about 20 pounds. But by Thanksgiving Jess had regained every pound. I saw this as a setback. I failed to see what was really happening: that by eating normally instead of dieting, she was finally learning to love her body, however fat or lumpy. This emerging attitude was about to transform not only her relationship with herself but our fractious mother-daughter relationship, too.

Shortly after her 27th birthday, Jess and Dan, her fiancé, came for a visit. A few days earlier, she had sent me a link to a video called A Fat Rant, by Joy Nash, a proponent of the fat acceptance movement. As we sat around the coffee table with wine and hummus, I mentioned having watched the video, and before I knew it, we were discussing the prejudice fat people deal with every day and how a person's weight is nobody's business but her own. It felt surreal to be able to talk to Jess about weight this way, and to hear her and Dan call themselves fat without flinching.

"Would you rather weigh less than you do?" I finally dared to ask. My husband stared at me wide-eyed, sure that this time I had really gone too far.

Jess thought about it. Dan thought about it. And their answer was, essentially, no.

A few months later, Jess and I went shopping at a plus-size store in Brooklyn— so much hipper than the store of my nightmare—to look for a wedding dress. After trying on a few, Jess decided she also needed a new bra and jeans. How many mothers and their daughters can go jeans shopping together without a dressing room meltdown? Amazingly, we could.

After seeing the Fat Rant video, I'd steeped myself in fat acceptance blogs and had finally become able to accept that Jess was not only fat but beautiful. Her weight was no longer the first thing I saw, or fretted about, or even thought about, when I was with my brilliant, funny, sexy, sensitive daughter. We seemed to have crossed some significant barrier.

But there's a catch: As much as I can embrace fat acceptance for Jess and Dan and their friends, I still can't embrace it for myself. The thought of letting go and just weighing whatever I'm destined to, no matter how much—well, it's scary. I think this bothers Jess. I think it interferes with our ability to be completely candid when talking about weight—but I can't help it. I'm just not there yet.

Oh, but Jess—she's there, emphatically so. That skilled, self-confident shimmy I watched at her belly dance recital did not come easily, but come it did, and it was a lovely thing to behold. That's the image that comes to me when I think about Jess's weight: her body in motion that evening, with a grace and a beauty I had never seen before. It didn't bother me that the midriff she exposed was fat. It didn't bother me because it so clearly didn't bother her.

Robin Marantz Henig is a freelance science writer based in New York.

Big and beautiful:

Jess Zimmerman, 2009

Jess Zimmerman, 2009

The Daughter's Story

"I was gross, lazy, and unfixable."

When I was 6 my mother, a journalist, wrote an article for Woman's Day called "Kids Get Fat Because They Eat Too Much...and Other Myths About Overweight Children." Under the main article was a sidebar about how she'd turned me from a slightly chubby 4-year-old into a slightly less chubby 6-year-old...by feeding me less. "I was gross, lazy, and unfixable."

This was typical. When Mom wrote about children and health, I appeared in the role of Fat Kid Saved by Diet or Exercise. The reality might have been that I ate no more than other kids, that I read a lot but also played a lot outside, that I wasn't even particularly fat. But such complexities weren't part of my role in my mother's narrative. I was an object lesson—proof that even fat kids could be salvaged.

The diets never worked for long, so my permanent role in real life became Fat Kid Who's Also a Failure. The 6-year-old in that first article is shown dancing ballet, eating yogurt for lunch, gazing joyfully out onto a slimmer future. In fact she couldn't bear to look at herself in a leotard, and was terrified that her mother would catch her using her milk money for chocolate milk instead of skim.

It's not that I had the world's biggest complex, or the worst food issues, or the most poisonous self-image. And I'm not the most textbook illustration of how fixation on a daughter's body can destroy her self-esteem. But this isn't only about the harm my mother unwittingly did me; it's about the harm the weight loss fantasy does to everyone.

Mom didn't allow me to eat fast food (which I've never missed) or dessert (which, lord, I did). When I was 9 I bargained with myself that if I went a month without sugar, I could have an ice cream sundae, something I'd never eaten before. But when I still stayed fat, all food became suspect.

At a sleepover in fifth grade, I was served sweetened cereal and was simultaneously repulsed and fascinated—it tasted awful, but it looked like dessert for breakfast, and I didn't even get dessert for dessert. Food took on a mystical but terrifying appeal, desirable and dangerous, and safe only when nobody was looking—and I resorted to sneaking and hoarding it. On average, I didn't eat more or worse than other kids, but I didn't have to. If you think you don't deserve food, everything starts to look like a binge.

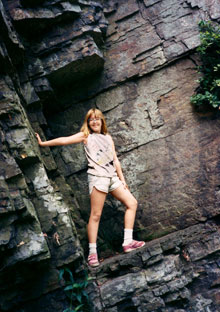

Jess, age 9

And there was no question in my mind that I didn't deserve food. I was oversize, clumsy, monstrous—like a different species—though pictures from my preteen years show that the biggest thing about me was actually my prescription glasses. My body was an albatross that marked me as slovenly, ugly, unworthy of love. I fantasized about sloughing it off, like the boy in the Narnia book who turns into a dragon and doesn't become human again until he painfully sheds his skin.

My mother never intended this—she only wanted a happy ending for me. But the ending she envisioned was the same one that played out in every kid's book with a fat character I had ever read: the one where the troubled chubster solves her inner turmoil and ends up svelte. Mom never envisioned an ending where the fat kid discovers that there was nothing wrong with her in the first place. Why would she? Nobody ever wrote that story.

It's difficult for a child to differentiate between someone who wants to armor her against an unjust world and someone who thinks that she's damaged. "What," I wondered, "is so deeply wrong with me that my mom, who only wants to love me, can't bring herself to love me how I am? And why can't I fix it?"

I kept waiting for the day when I'd reach the happy, skinny ending and get to start on the sequel. I'd diet myself thin at last, and then I'd be vivacious and graceful and sought after, and I would be allowed to wear tank tops and eat, and my life could begin. As I ate less and got fatter, these scenarios became more drastic: They now involved wasting away from a serious illness, which I suspected was the only way I'd become as gaunt as I wanted to be. When I started getting brutal stomach pains in high school, my heart leapt—maybe this was it!

My mother never intended this—she only wanted a happy ending for me. But the ending she envisioned was the same one that played out in every kid's book with a fat character I had ever read: the one where the troubled chubster solves her inner turmoil and ends up svelte. Mom never envisioned an ending where the fat kid discovers that there was nothing wrong with her in the first place. Why would she? Nobody ever wrote that story.

It's difficult for a child to differentiate between someone who wants to armor her against an unjust world and someone who thinks that she's damaged. "What," I wondered, "is so deeply wrong with me that my mom, who only wants to love me, can't bring herself to love me how I am? And why can't I fix it?"

I kept waiting for the day when I'd reach the happy, skinny ending and get to start on the sequel. I'd diet myself thin at last, and then I'd be vivacious and graceful and sought after, and I would be allowed to wear tank tops and eat, and my life could begin. As I ate less and got fatter, these scenarios became more drastic: They now involved wasting away from a serious illness, which I suspected was the only way I'd become as gaunt as I wanted to be. When I started getting brutal stomach pains in high school, my heart leapt—maybe this was it!

It wasn't. The stomach pains happened because when the life-threatening disease failed to materialize, I had turned to another twisted weight loss strategy: disordered eating. Sometime around the age of 13 I started to read first-person stories about anorexia for ideas on how to control my food intake. I hid behind fussiness—suddenly I didn't like anything with more than three ingredients, or red meat, or fish, or cheese, or anything strongly spiced. (As late as college, a friend bet me that he could recite my entire grocery list. He named six items and got it basically right.) My teen magazines were full of tips on how to throw up without attracting notice. I didn't binge, but I would throw up because I'd had a full meal, or because I'd scarfed a contraband late-night bowl of ice cream, or just because it was the end of the day.

The eating disorder stories tended to harp on the fact that girls who couldn't control their eating couldn't control anything in their lives, and as I got older I started to believe that everything about me was wrong. Though I often exuded a toughness that was mistaken for confidence, I doubted not only my attractiveness and right to exist in the world as a fat person but also my intelligence and talent and general worth. Once I started dating, I sought out boys and men who shared my low opinion of myself. One praised me for recognizing that my weight was "a problem"—he didn't care so much whether I was fat, as long as I knew I wasn't okay.

When I went away to college, I was still on a semipermanent diet punctuated by furtive eating, still pretending to be picky to hide my food restriction, and still looking for people to tell me how lousy I was. I caromed from asceticism to sugar overdose, and gained weight despite spending eight hours a week at fencing practice. (Around this time, I also had my metabolic rate tested. Based on my height and weight, it was significantly slower than average. It's possible that this was always the case. On the other hand, I know from Mom's own articles that restrictive eating can do a number on a person's metabolism.)

In my mind I was still the gross, lazy, unfixable kid. But in the tiny empowerment bubble of a women's college, there were a host of new narratives I hadn't considered. I discovered books, articles, and indie zines offering strange new ideas: that fat people could be happy and healthy and even loved, that we weren't necessarily damaged, that beauty ideals controlled women by making them waste their energy on hating themselves. That the desire to eat food was sometimes just the body's way of taking care of itself. The old narrative—in which I would remain trapped in a loathsome body until I earned love and happiness through slimness—started to fade.

Sophomore year, Mom wrote an article tut-tutting about how the people on campus who told me to "honor my hunger" were only ruining my diet. I ran a campuswide campaign for Love Your Body Day and asked Mom to quit writing about me.

And eventually I started to write. Books, magazines, and literature on campus had planted the suspicion that there was a less painful way to live, and when I rediscovered these ideas in the blogosphere, I found myself repeating and reformulating them. In communicating with others, I started convincing myself.

Along the way, I retooled my vocabulary. Fat, the word I'd scrawled accusingly in marker on my offending thighs in high school, was just a neutral way of describing a body; if there's nothing inherently shameful in fatness, there's no reason to hide behind euphemisms. And the word health, so often used as a club to beat fat people with, needed redefining, too. There's nothing healthy about fearing food and using exercise as a whip. A better goal is to exercise for fun and truly eat well—not less, not using different rules, but in a way that's more nourishing and more conscious. By my mid-20s, I was not only eating more normally—I had added new kinds of exercise to my routine for the sheer fun of it: belly dance, yoga, hula hooping. My weight stayed the same, but I started to really live in the body I was now feeding and taking out to play. I realized I wasn't trapped in the old cycle of failure, denial, and shame.

These days I can write about my body—and even, cautiously, let my mother write about it—because I've jettisoned the old narratives and started to scratch out a new one. It's a complicated story, with an unpredictable plot—good days, bad days, a pervasive sense of shame that's hard to shake. But I'm finding that the main character is much more healthy, stable, and worthwhile than I'd ever known.

Jess Zimmerman is a journalist who lives near Washington, D.C.

From the December 2012 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine.

Hair and Makeup: Danielle Cirilli for AristsbyTimothyPriano.com