The Fat Fight

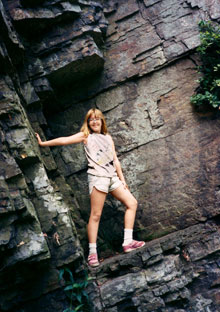

Jess, age 9

PAGE 5

And there was no question in my mind that I didn't deserve food. I was oversize, clumsy, monstrous—like a different species—though pictures from my preteen years show that the biggest thing about me was actually my prescription glasses. My body was an albatross that marked me as slovenly, ugly, unworthy of love. I fantasized about sloughing it off, like the boy in the Narnia book who turns into a dragon and doesn't become human again until he painfully sheds his skin.

My mother never intended this—she only wanted a happy ending for me. But the ending she envisioned was the same one that played out in every kid's book with a fat character I had ever read: the one where the troubled chubster solves her inner turmoil and ends up svelte. Mom never envisioned an ending where the fat kid discovers that there was nothing wrong with her in the first place. Why would she? Nobody ever wrote that story.

It's difficult for a child to differentiate between someone who wants to armor her against an unjust world and someone who thinks that she's damaged. "What," I wondered, "is so deeply wrong with me that my mom, who only wants to love me, can't bring herself to love me how I am? And why can't I fix it?"

I kept waiting for the day when I'd reach the happy, skinny ending and get to start on the sequel. I'd diet myself thin at last, and then I'd be vivacious and graceful and sought after, and I would be allowed to wear tank tops and eat, and my life could begin. As I ate less and got fatter, these scenarios became more drastic: They now involved wasting away from a serious illness, which I suspected was the only way I'd become as gaunt as I wanted to be. When I started getting brutal stomach pains in high school, my heart leapt—maybe this was it!

My mother never intended this—she only wanted a happy ending for me. But the ending she envisioned was the same one that played out in every kid's book with a fat character I had ever read: the one where the troubled chubster solves her inner turmoil and ends up svelte. Mom never envisioned an ending where the fat kid discovers that there was nothing wrong with her in the first place. Why would she? Nobody ever wrote that story.

It's difficult for a child to differentiate between someone who wants to armor her against an unjust world and someone who thinks that she's damaged. "What," I wondered, "is so deeply wrong with me that my mom, who only wants to love me, can't bring herself to love me how I am? And why can't I fix it?"

I kept waiting for the day when I'd reach the happy, skinny ending and get to start on the sequel. I'd diet myself thin at last, and then I'd be vivacious and graceful and sought after, and I would be allowed to wear tank tops and eat, and my life could begin. As I ate less and got fatter, these scenarios became more drastic: They now involved wasting away from a serious illness, which I suspected was the only way I'd become as gaunt as I wanted to be. When I started getting brutal stomach pains in high school, my heart leapt—maybe this was it!

Photo: Courtesy Jess Zimmerman