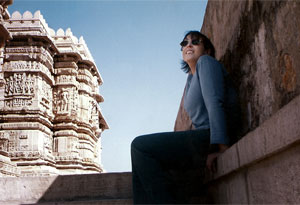

Photo: Courtesy of Katherine Russell Rich

Katherine Russell Rich died on April 3, at age 56, after an almost 25-year (yes, that’s what we said) battle with cancer. While death, no matter how expected, is always a shock, to those of us who knew Kathy for the better part of three decades, the news feels especially unbelievable. Kathy was often on her way to or from one treatment or another—though she rarely talked about it—but she ALWAYS came back to have another lunch, teach another course, write another book, make another friend. Her intelligence, her fierceness, her just-the-right-amount-of-kooky sensibility shows through in this piece she wrote for O in June 2010, and will inspire us always.—Sara Nelson

In 1988 I was diagnosed with cancer and launched into an alien world—a bizarre, distorted landscape—and I didn't have a map. Where I'd come from, people defined their lives by the things they loved: their friends, their family, those nights in late summer when shooting stars are as thick as miraculous blizzards in the sky. But in this new world, definitions can be hard to come by. Here, certainty is an illusion. Here, you live among outlaws, your body's own cells: Whole phalanxes of them turn mutinous, become silent killers. This is a country that's both narrow and vast, where geography bends at the edges and landmarks vanish like Cheshire cats. "Oh, we don't use that drug anymore," a doctor will say, five minutes after the drug was invented. So you have to become your own cartographer, make your own way. You grow fluent in an ornate language you won't use on the other side. "Neoplasia" and "hematopoietic" are words that can startle new acquaintances, especially if, as is true with me, for the most part your treatments don't alter your appearance. If your side effects are outwardly mild, you slide across borders undetected. (In my case, there was a notable exception: the stretch, 15 years back, when I had a bone marrow transplant and was feeble and white, a bald worm woman, ghostly. When I looked in the mirror then, what I saw was like an unmasking—as if up to now, I'd been passing myself off as a healthy person. The vision was shocking, but not unexpected.)

Five years later, the doctors told me that the average life expectancy was two and a half years with stage IV breast cancer, breast being the variety I have. (Stage IV means the cancer has spread, is deadly. No turning back. No cure.) I hasten to add that two and a half years is just an average. It's not unusual for people to reach five, even ten. Get much past that, though, and they decide you fall into a small subcategory of people who inexplicably live for years: 20, 30, or with all the new stuff coming down the pike, who knows? Maybe a normal life span.

Here, through the looking glass, in the back of the beyond, there is no normal. There is no certainty, but that's true in the old world as well. (This is something many people don't want to know, so I mostly keep it to myself.) Another truth that applies to both places: Uncertainty is not necessarily to be feared. It can make your life bloom, give you power; at least that's what I've found. "So what?" I'd tell myself. "Just try it." Sometimes choices can be ill-advised; frequently, at first, some of mine were. Later on, when I got my footing, wondrous things occurred.

In the megatron months before and after my bone marrow transplant, I conducted an experiment: What would happen if I said exactly what I thought? Fights on planes, that's what. Gallows-humor jokes that can make people blanch. "Sure takes the term out of terminal," said of advanced but sluggish cancer, requires a special audience. Near-ejection from art galleries. In that case I'd opened my mouth, as if possessed, and voiced what had been my private opinion of the brittle gallery owner who was aggressively dismissive when I politely asked for directions. What I said, exactly, was: "You're a bitch." She looked startled, answered slowly, "Well, maybe I am." And I felt, for the moment, elated.

When you're afraid to move forward, ask yourself, "What's the worst that can happen?"

Photo: Courtesy of Katherine Russell Rich

There's a reason we have an internal censor. You can do a lot of damage if you disconnect yours, even in just a couple of months, even when warm-up chemotherapy is knocking the fight out of you, which is what was happening one morning when I nearly lost it at the office. New York was in the middle of a brutish, hell's-breath summer. I'd stopped being in the mood to smell any more freaking flowers, was just trudging through each day, when my phone rang and a woman I knew, a writer noteworthy for self-absorption, said, "Um, hi? I have a question? Do you think you can recommend a new shampoo for me?" When I replied that, since I was now bald, I hadn't washed my hair in three months, she pouted. "But you work at a beauty magazine," she said, as if she didn't know the rest. (Everyone did.) I exercised restraint on the phone, but later let loose on her to such an extent that when we run into each other at a party even today, her face takes on the tense expression of someone feeling around in a frozen turkey for the giblets. I didn't like who I was starting to become then, though I do like who I eventually became. However clumsy and crude I was during those months, they were the beginning of learning to take on power, of discovering how to speak up. It would be a while before I got comfortable with it.

Ten years after diagnosis, three years after my bone marrow transplant: At 42, I didn't yet know that I fell into any subcategory, only that I was several years past my stated expiration date. "The way this cancer's come on so fast," the raw-boned oncologist who diagnosed me with stage IV said, "you have a year or two to live." Years later, she'll no longer be a practicing doctor and I'll be alive and kicking, but again, I didn't know that yet.

But here are some things I was starting to know. When you're swamped by fear, ask yourself: "How are you right now? Right now, are you in the hospital? Right now, are tumors swelling in your spine, cracking bones, forcing you into a fetal position?" The one time that they were doing just that, I was flown to North Carolina for a procedure that, it turned out, I was too sick to begin. In a last-ditch effort, a doctor tried a hormone treatment no one had used much since the '60s, and in a turn that still seems impossible, the cancer, for no good reason, retreated and lay down, where it has pretty much remained. Every so often it snarls and raises its head, and we switch treatments. We smack it back down.

"How are you now?" I learned to ask myself whenever I feel an ominous buzz in a bone, whenever uncertainty threatens to swamp me. "How are you right now?" And each time, the answer is, "Fine. Stay right here, in this day, stay right here in your mind." That's one of the things I say to counsel myself. Also, "Leave room for the God factor—no one can say, with ultimate truth, what will happen." And: "When you're afraid to move forward, ask yourself what's the worst that can happen." One night, on chemo, I was comparing notes on the phone with a friend, another cancer patient, who said, "When you're fighting the insurance companies, don't you ever think, 'What are they going to do, kill me?'" It is, I've decided, an exemplary motto.

Furthermore, this: "Keep going and don't look down, if you do you'll hit," though this one I can't manage perfectly. I still think I'm going to die soon. I fall and hit bottom all the time.

I'll have adventures of the mind—and, perhaps, some impact on the world...

Ten years after diagnosis, three years after my bone marrow transplant: At 42, I didn't yet know that I fell into any subcategory, only that I was several years past my stated expiration date. "The way this cancer's come on so fast," the raw-boned oncologist who diagnosed me with stage IV said, "you have a year or two to live." Years later, she'll no longer be a practicing doctor and I'll be alive and kicking, but again, I didn't know that yet.

But here are some things I was starting to know. When you're swamped by fear, ask yourself: "How are you right now? Right now, are you in the hospital? Right now, are tumors swelling in your spine, cracking bones, forcing you into a fetal position?" The one time that they were doing just that, I was flown to North Carolina for a procedure that, it turned out, I was too sick to begin. In a last-ditch effort, a doctor tried a hormone treatment no one had used much since the '60s, and in a turn that still seems impossible, the cancer, for no good reason, retreated and lay down, where it has pretty much remained. Every so often it snarls and raises its head, and we switch treatments. We smack it back down.

"How are you now?" I learned to ask myself whenever I feel an ominous buzz in a bone, whenever uncertainty threatens to swamp me. "How are you right now?" And each time, the answer is, "Fine. Stay right here, in this day, stay right here in your mind." That's one of the things I say to counsel myself. Also, "Leave room for the God factor—no one can say, with ultimate truth, what will happen." And: "When you're afraid to move forward, ask yourself what's the worst that can happen." One night, on chemo, I was comparing notes on the phone with a friend, another cancer patient, who said, "When you're fighting the insurance companies, don't you ever think, 'What are they going to do, kill me?'" It is, I've decided, an exemplary motto.

Furthermore, this: "Keep going and don't look down, if you do you'll hit," though this one I can't manage perfectly. I still think I'm going to die soon. I fall and hit bottom all the time.

I'll have adventures of the mind—and, perhaps, some impact on the world...

Twelve years after diagnosis, five years after the transplant: I've quit my profession, magazine editing, and become a writer. The illness has made physical adventures harder. "Fine," I have decided. "Then I'll have adventures of the mind—and, perhaps, some impact on the world." When I was told I was going to die, I was shredded to realize I hadn't made any real difference. The life of a writer was uncertain, but as a writer, it seemed, I might leave a mark.

Out of the blue one day a newspaper assignment came through, to go to India and interview the Dalai Lama's doctor. Just for two weeks, but I was terrified to travel there alone, terrified of all the ghastly bad ends that awaited me in the unknown.

So what? "Just try it. Stay right here, in this day." After all, I only had to book the ticket, not meet 14 terrible fates.

And so I took the trip. And when I returned I took a Hindi lesson, for fun, to preserve the memory. Each class forced me into a concentration that shifted between frustration and wonder. Sentences produced vertigo. Verbs came at the end. "I this shop from some fruit buy want" could retain its meaning—"I want to buy some fruit from this shop"—only if I didn't look down. I'd hold my breath and push off, like skiing.

Then a friend suggested I spend a year in India learning Hindi. "Just try it." And so I moved to the desert state of Rajasthan, to an old women's-quarters of a noble family's haveli, an ancient, sloping home. Murals of tiger hunts ran the length of the walls. In the thin lane below, magnificent temples tucked between shops, I'd pass two tired-looking old men in a storefront, bent over the silver anklets they sold. Down the street, a cheerful boy polished bracelets in a vat of milky water. When I'd stop to watch, his father, his fingers mehndi'ed red, would advise aritha, an Indian fruit, for my hair. He brought out three small, wrinkled orbs and told me to boil them in water. "For soft and silky," he said in Hindi.

Now, when fear threatens to shut me down...

Out of the blue one day a newspaper assignment came through, to go to India and interview the Dalai Lama's doctor. Just for two weeks, but I was terrified to travel there alone, terrified of all the ghastly bad ends that awaited me in the unknown.

So what? "Just try it. Stay right here, in this day." After all, I only had to book the ticket, not meet 14 terrible fates.

And so I took the trip. And when I returned I took a Hindi lesson, for fun, to preserve the memory. Each class forced me into a concentration that shifted between frustration and wonder. Sentences produced vertigo. Verbs came at the end. "I this shop from some fruit buy want" could retain its meaning—"I want to buy some fruit from this shop"—only if I didn't look down. I'd hold my breath and push off, like skiing.

Then a friend suggested I spend a year in India learning Hindi. "Just try it." And so I moved to the desert state of Rajasthan, to an old women's-quarters of a noble family's haveli, an ancient, sloping home. Murals of tiger hunts ran the length of the walls. In the thin lane below, magnificent temples tucked between shops, I'd pass two tired-looking old men in a storefront, bent over the silver anklets they sold. Down the street, a cheerful boy polished bracelets in a vat of milky water. When I'd stop to watch, his father, his fingers mehndi'ed red, would advise aritha, an Indian fruit, for my hair. He brought out three small, wrinkled orbs and told me to boil them in water. "For soft and silky," he said in Hindi.

Now, when fear threatens to shut me down...

Twenty-two years after diagnosis, 15 years after the transplant, right now. "When you were really sick, you had to test your limits," a friend had said on the eve of the second trip, after confessing she was worried I'd be found by the side of some road. "And now maybe you have to keep doing that." I was peeved at the time, thinking she was implying I was down a few marbles, but now I think there was some truth to what she said. That experience was only partly about learning Hindi; it was as much about learning not to accept limits—of cancer, of anything.

What I know now: Even if I had had a map from the start, it wouldn't have done me any good. Like old lives, maps in this world, or any world, are something of an illusion. They change all the time. Now, when fear threatens to shut me down, I think back to how, after I'd told my oncologist I wanted to go live in India, he was silent for a bit. I don't think he'd had a patient with advanced cancer ask to do anything like this. "All right," he said finally, "but you have to be closely monitored." I agreed, then got over there to find there wasn't an oncologist within hundreds of miles of the town where I'd landed. We rallied, he and I. The doctor did his best to answer all crazed late-night e-mails—"I feel a pain in my hip. Do you think that's from cancer or riding in rickshaws?"—and I set up a relay system, where vials of my blood repeatedly changed hands before ending up at a lab in Mumbai to be tested.

In other words, we made it up as we went along, my doctor and I, something you learn to do if you stick around long enough. And here's something else you find: You may not have known it, but, really, that's all you've been doing the whole time. Along with everyone else.

Read another amazing survival story

What I know now: Even if I had had a map from the start, it wouldn't have done me any good. Like old lives, maps in this world, or any world, are something of an illusion. They change all the time. Now, when fear threatens to shut me down, I think back to how, after I'd told my oncologist I wanted to go live in India, he was silent for a bit. I don't think he'd had a patient with advanced cancer ask to do anything like this. "All right," he said finally, "but you have to be closely monitored." I agreed, then got over there to find there wasn't an oncologist within hundreds of miles of the town where I'd landed. We rallied, he and I. The doctor did his best to answer all crazed late-night e-mails—"I feel a pain in my hip. Do you think that's from cancer or riding in rickshaws?"—and I set up a relay system, where vials of my blood repeatedly changed hands before ending up at a lab in Mumbai to be tested.

In other words, we made it up as we went along, my doctor and I, something you learn to do if you stick around long enough. And here's something else you find: You may not have known it, but, really, that's all you've been doing the whole time. Along with everyone else.

Read another amazing survival story