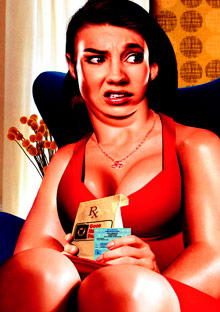

Illustration: Eddie Guy

It's the side effect nobody thinks about until they look down and realize—hello!—they've gained 10, 20, 30 pounds. Yet almost any medication, from antidepressants to antihistamines, has the potential to make you ravenous or sluggish, or meddle with your metabolism. Here are the worst offenders and how to fight back.

Mired in depression and a vicious work dispute, Barbara Tunstall placed her hopes on the antidepressant Remeron. Her doctor warned that food cravings were a potential side effect of the drug, but the 45-year-old Maryland insurance specialist put such concerns aside—initially. Tunstall felt so much better on Remeron that she soon found the energy to resolve her work troubles. Then she realized that she was gaining weight at an alarming pace: Just six months into her treatment, she had put on 30 pounds. "I'd eat anything in my way," she says. "I knew I was out of control, but I still couldn't stop." Tunstall and her psychiatrist tried to rein in her constant eating—including adding a course of Topamax, an antiseizure medication known for its ability to suppress appetite—and yet nothing helped. The weight gain was adding a whole new list of frustrations and anxieties. Finally, her doctor weaned her off Remeron in favor of the antidepressant Celexa, a milder drug. Her cravings subsided, and Tunstall gradually shed the weight.

Fewer than 5 percent of Americans who are overweight got that way because of their medications, suggests research by Louis Aronne, MD, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Program at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and a past president of the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. That's not a staggering number, but doctors are concerned nonetheless. Heart disease, diabetes, depression, and cancer are on the rise, and it's the drugs used to treat them that are most likely to pack on the pounds. "I think this is an underrecognized problem," says Aronne. "Most of the people we see simply aren't aware of the relationship between their weight and the drugs they're taking and that it's something they need to watch."

Some drugs drive up weight by making you drowsy or lethargic, which means you'll burn fewer calories throughout the day. Others affect brain chemistry in a way that trips hunger switches. Because everyone reacts differently to these drugs, it's virtually impossible to predict how much you might gain during treatment. What's more, remedies that aren't known for adding pounds still could. "Almost any medication can cause changes in weight," says Lawrence Cheskin, MD, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and director of the Johns Hopkins Weight Management Center. "Generally speaking, people who are sick lose their appetite. So when they're successfully treated for an illness, they may begin to eat more. If you're not aware of that consequence, it's easy to go overboard."

The best way to preserve your shape is to monitor yourself closely. "Anytime you start a new therapy, weigh yourself every morning," says George Blackburn, MD, PhD, associate director of the division of nutrition at Harvard Medical School, where he teaches a course that includes a section on drugs and weight gain. "Five pounds is your red flag to check with a physician." Act sooner if you suddenly feel excessively hungry or lethargic. You may have the option of changing prescriptions. "Increasingly, drugs linked to weight problems are being replaced with second-generation alternatives," Blackburn explains. Some are so new that your family physician may not be aware of them, so consider seeing a specialist. A doctor who's trained to treat your specific problem, or at least an internist or an endocrinologist with an interest in obesity issues, will be up on the latest treatments.

In some cases, switching drugs—or readjusting the dosage—isn't an option. But according to Blackburn, eating 100 to 200 fewer calories each day is enough to counteract the kind of weight gain you'd experience on most drugs, especially if you increase your exercise. Below, the drugs most likely to tip the scale and what you can do about it.

Antidepressants: Tricyclic medicines can add as many as nine pounds a month; lithium-based mood stabilizers, two and a half pounds. Another class of antidepressants, SSRIs, target the mood-and-appetite-related neurochemical serotonin and may also cause weight gain. If you begin to gain on one of these, look into switching to a bupropion drug; these target neurochemicals that don't increase hunger.

Antipsychotics: Haloperidol and clozapine can have a big effect on metabolism and appetite, adding as many as five pounds a week. Usually people on these drugs are already being closely monitored by a psychiatrist, so if the pounds start to add up, don't hesitate to ask about alternatives such as atypical antipsychotics, which appear to be weight neutral.

Antihistamines, Sleep Aids: Many over-the-counter allergy remedies and sleeping pills contain diphenhydramine, an ingredient that can leave you drowsy during the day and interfere with your sleep patterns at night, reducing the number of calories you're burning.

Blood Pressure Medication: Both alpha- and beta-blockers can cause fatigue, which may add pounds in some patients (the amounts reported vary wildly). If your energy fades, look into ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers.

Cancer Therapy: Women with breast cancer are likely to gain weight during chemotherapy. The exact reasons for this are poorly understood, but doctors believe the treatment can slow metabolism.Also, the anti-estrogen drug tamoxifen may increase appetite; Decadron, a steroid used on cancer patients, is another potential culprit. Additionally, chemotherapy often induces early menopause, which can add pounds. Switching drugs isn't an option, so work with your doctors to develop an eating-and-exercise plan.

Diabetes Drugs: Insulin helps process blood sugar by depositing it into cells. Insulin and drugs known as sulfonylureas can bring on bouts of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), which stimulates appetite. Some patients report gaining up to 11 pounds during the first three to 12 months of treatment. Ask about weight-neutral medications, such as metformin.

Migraine Medicines: Those based on valproic acid can stimulate hunger. These days, doctors are more likely to prescribe Topamax or Imitrex. Neither medicine is associated with weight gain, and both are thought to be safer overall.

Steroids: Oral corticosteroids, commonly used to treat conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and chronic inflammation, add pounds in multiple ways. They rob calories from your energy stores and send them to fat cells. So not only are you adding pounds but your energy is being compromised, which drives up your cravings. Some people gain as many as 28 pounds on steroids. Ask about switching to prescription-strength NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen.

If you gain weight due to medication, the key is patience. "When you go off the drug, you won't lose weight as fast as you gained it," says Aronne. "But by taking control of this aspect of your treatment, you'll start to see results."

Sara Reistad-Long is a writer living in New York. She has written for Esquire and Real Simple.